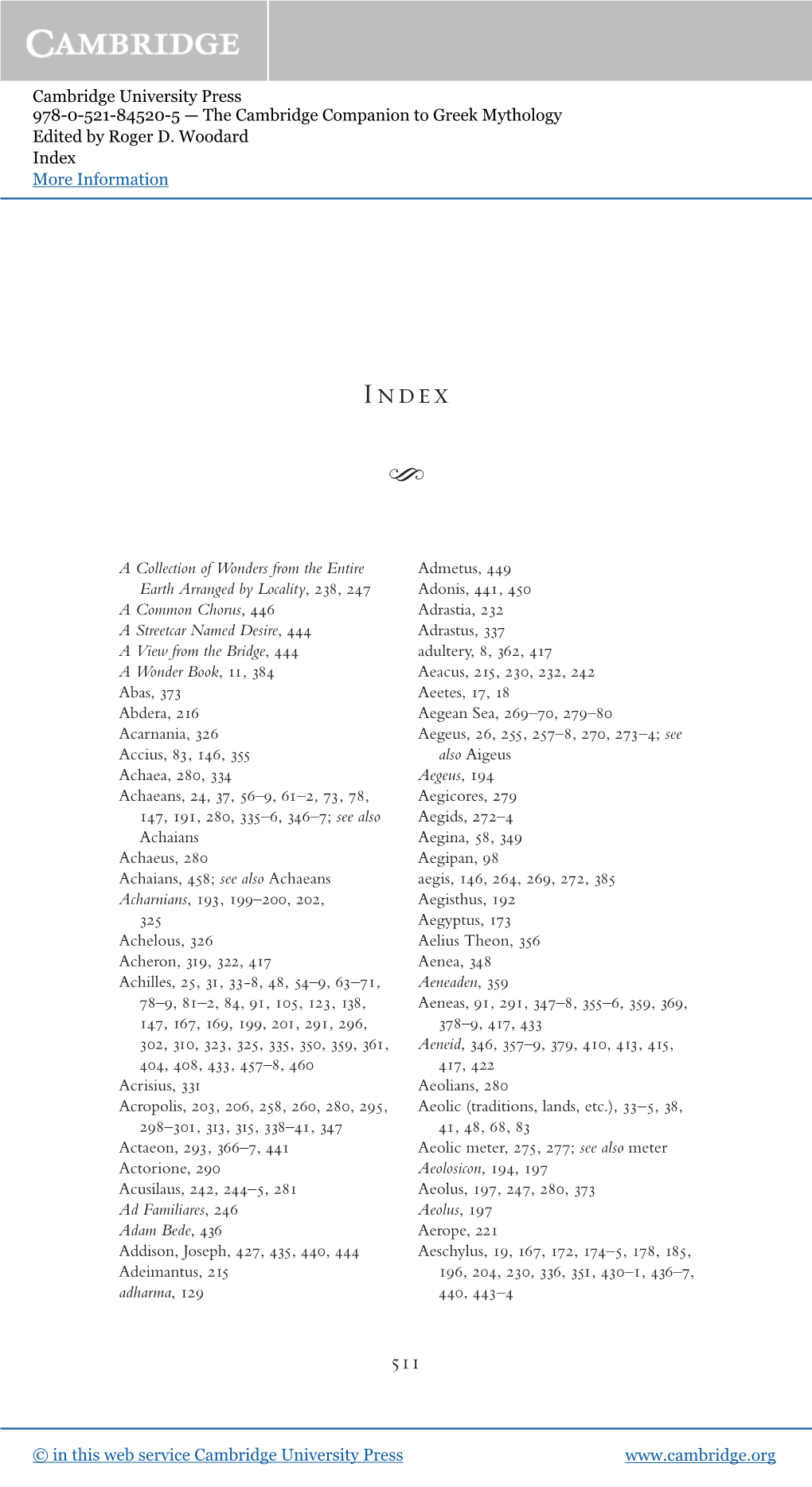

The Cambridge Companion to Greek Mythology Edited by Roger D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Banished to the Black Sea: Ovid's Poetic

BANISHED TO THE BLACK SEA: OVID’S POETIC TRANSFORMATIONS IN TRISTIA 1.1 A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of The School of Continuing Studies and of The Graduate School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Liberal Studies By Christy N. Wise, M.A. Georgetown University Washington, D.C. October 16, 2014 BANISHED TO THE BLACK SEA: OVID’S POETIC TRANSFORMATIONS IN TRISTIA 1.1 Christy N. Wise, M.A. Mentor: Charles A. McNelis, Ph.D. ABSTRACT After achieving an extraordinarily successful career as an elegiac poet in the midst of the power, glory and creativity of ancient Rome during the start of the Augustan era, Ovid was abruptly separated from the stimulating community in which he thrived, and banished to the outer edge of the Roman Empire. While living the last nine or ten years of his life in Tomis, on the eastern shore of the Black Sea, Ovid steadily continued to compose poetry, producing two books of poems and epistles, Tristia and Epistulae ex Ponto, and a 644-line curse poem, Ibis, all written in elegiac couplets. By necessity, Ovid’s writing from relegatio (relegation) served multiple roles beyond that of artistic creation and presentation. Although he continued to write elegiac poems as he had during his life in Rome, Ovid expanded the structure of those poems to portray his life as a relegatus and his estrangement from his beloved homeland, thereby redefining the elegiac genre. Additionally, and still within the elegiac structure, Ovid changed the content of his poetry in order to defend himself to Augustus and request assistance from friends in securing a reduced penalty or relocation closer to Rome. -

Kretan Cult and Customs, Especially in the Classical and Hellenistic Periods: a Religious, Social, and Political Study

i Kretan cult and customs, especially in the Classical and Hellenistic periods: a religious, social, and political study Thesis submitted for degree of MPhil Carolyn Schofield University College London ii Declaration I, Carolyn Schofield, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been acknowledged in the thesis. iii Abstract Ancient Krete perceived itself, and was perceived from outside, as rather different from the rest of Greece, particularly with respect to religion, social structure, and laws. The purpose of the thesis is to explore the bases for these perceptions and their accuracy. Krete’s self-perception is examined in the light of the account of Diodoros Siculus (Book 5, 64-80, allegedly based on Kretan sources), backed up by inscriptions and archaeology, while outside perceptions are derived mainly from other literary sources, including, inter alia, Homer, Strabo, Plato and Aristotle, Herodotos and Polybios; in both cases making reference also to the fragments and testimonia of ancient historians of Krete. While the main cult-epithets of Zeus on Krete – Diktaios, associated with pre-Greek inhabitants of eastern Krete, Idatas, associated with Dorian settlers, and Kretagenes, the symbol of the Hellenistic koinon - are almost unique to the island, those of Apollo are not, but there is good reason to believe that both Delphinios and Pythios originated on Krete, and evidence too that the Eleusinian Mysteries and Orphic and Dionysiac rites had much in common with early Kretan practice. The early institutionalization of pederasty, and the abduction of boys described by Ephoros, are unique to Krete, but the latter is distinct from rites of initiation to manhood, which continued later on Krete than elsewhere, and were associated with different gods. -

Naming the Extrasolar Planets

Naming the extrasolar planets W. Lyra Max Planck Institute for Astronomy, K¨onigstuhl 17, 69177, Heidelberg, Germany [email protected] Abstract and OGLE-TR-182 b, which does not help educators convey the message that these planets are quite similar to Jupiter. Extrasolar planets are not named and are referred to only In stark contrast, the sentence“planet Apollo is a gas giant by their assigned scientific designation. The reason given like Jupiter” is heavily - yet invisibly - coated with Coper- by the IAU to not name the planets is that it is consid- nicanism. ered impractical as planets are expected to be common. I One reason given by the IAU for not considering naming advance some reasons as to why this logic is flawed, and sug- the extrasolar planets is that it is a task deemed impractical. gest names for the 403 extrasolar planet candidates known One source is quoted as having said “if planets are found to as of Oct 2009. The names follow a scheme of association occur very frequently in the Universe, a system of individual with the constellation that the host star pertains to, and names for planets might well rapidly be found equally im- therefore are mostly drawn from Roman-Greek mythology. practicable as it is for stars, as planet discoveries progress.” Other mythologies may also be used given that a suitable 1. This leads to a second argument. It is indeed impractical association is established. to name all stars. But some stars are named nonetheless. In fact, all other classes of astronomical bodies are named. -

The Cambridge Companion to Greek Mythology (2007)

P1: JzG 9780521845205pre CUFX147/Woodard 978 0521845205 Printer: cupusbw July 28, 2007 1:25 The Cambridge Companion to GREEK MYTHOLOGY S The Cambridge Companion to Greek Mythology presents a comprehensive and integrated treatment of ancient Greek mythic tradition. Divided into three sections, the work consists of sixteen original articles authored by an ensemble of some of the world’s most distinguished scholars of classical mythology. Part I provides readers with an examination of the forms and uses of myth in Greek oral and written literature from the epic poetry of the eighth century BC to the mythographic catalogs of the early centuries AD. Part II looks at the relationship between myth, religion, art, and politics among the Greeks and at the Roman appropriation of Greek mythic tradition. The reception of Greek myth from the Middle Ages to modernity, in literature, feminist scholarship, and cinema, rounds out the work in Part III. The Cambridge Companion to Greek Mythology is a unique resource that will be of interest and value not only to undergraduate and graduate students and professional scholars, but also to anyone interested in the myths of the ancient Greeks and their impact on western tradition. Roger D. Woodard is the Andrew V.V.Raymond Professor of the Clas- sics and Professor of Linguistics at the University of Buffalo (The State University of New York).He has taught in the United States and Europe and is the author of a number of books on myth and ancient civiliza- tion, most recently Indo-European Sacred Space: Vedic and Roman Cult. Dr. -

MONEY and the EARLY GREEK MIND: Homer, Philosophy, Tragedy

This page intentionally left blank MONEY AND THE EARLY GREEK MIND How were the Greeks of the sixth century bc able to invent philosophy and tragedy? In this book Richard Seaford argues that a large part of the answer can be found in another momentous development, the invention and rapid spread of coinage, which produced the first ever thoroughly monetised society. By transforming social relations, monetisation contributed to the ideas of the universe as an impersonal system (presocratic philosophy) and of the individual alienated from his own kin and from the gods (in tragedy). Seaford argues that an important precondition for this monetisation was the Greek practice of animal sacrifice, as represented in Homeric epic, which describes a premonetary world on the point of producing money. This book combines social history, economic anthropology, numismatics and the close reading of literary, inscriptional, and philosophical texts. Questioning the origins and shaping force of Greek philosophy, this is a major book with wide appeal. richard seaford is Professor of Greek Literature at the University of Exeter. He is the author of commentaries on Euripides’ Cyclops (1984) and Bacchae (1996) and of Reciprocity and Ritual: Homer and Tragedy in the Developing City-State (1994). MONEY AND THE EARLY GREEK MIND Homer, Philosophy, Tragedy RICHARD SEAFORD cambridge university press Cambridge, New York, Melbourne, Madrid, Cape Town, Singapore, São Paulo Cambridge University Press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge cb2 2ru, UK Published in the United States of America by Cambridge University Press, New York www.cambridge.org Information on this title: www.cambridge.org/9780521832281 © Richard Seaford 2004 This publication is in copyright. -

Plato's Symposium: the Ethics of Desire

Plato’s Symposium: The Ethics of Desire FRISBEE C. C. SHEFFIELD 1 Contents Introduction 1 1. Ero¯s and the Good Life 8 2. Socrates’ Speech: The Nature of Ero¯s 40 3. Socrates’ Speech: The Aim of Ero¯s 75 4. Socrates’ Speech: The Activity of Ero¯s 112 5. Socrates’ Speech: Concern for Others? 154 6. ‘Nothing to do with Human AVairs?’: Alcibiades’ Response to Socrates 183 7. Shadow Lovers: The Symposiasts and Socrates 207 Conclusion 225 Appendix : Socratic Psychology or Tripartition in the Symposium? 227 References 240 Index 249 Introduction In the Symposium Plato invites us to imagine the following scene: A pair of lovers are locked in an embrace and Hephaestus stands over them with his mending tools asking: ‘What is it that you human beings really want from each other?’ The lovers are puzzled, and he asks them again: ‘Is this your heart’s desire, for the two of you to become parts of the same whole, and never to separate, day or night? If that is your desire, I’d like to weld you together and join you into something whole, so that the two of you are made into one. Look at your love and see if this is what you desire: wouldn’t this be all that you want?’ No one, apparently, would think that mere sex is the reason each lover takes such deep joy in being with the other. The soul of each lover apparently longs for something else, but cannot say what it is. The beloved holds out the promise of something beyond itself, but that something lovers are unable to name.1 Hephaestus’ question is a pressing one. -

The Recollections of Encolpius

The Recollections of Encolpius ANCIENT NARRATIVE Supplementum 2 Editorial Board Maaike Zimmerman, University of Groningen Gareth Schmeling, University of Florida, Gainesville Heinz Hofmann, Universität Tübingen Stephen Harrison, Corpus Christi College, Oxford Costas Panayotakis (review editor), University of Glasgow Advisory Board Jean Alvares, Montclair State University Alain Billault, Université Jean Moulin, Lyon III Ewen Bowie, Corpus Christi College, Oxford Jan Bremmer, University of Groningen Ken Dowden, University of Birmingham Ben Hijmans, Emeritus of Classics, University of Groningen Ronald Hock, University of Southern California, Los Angeles Niklas Holzberg, Universität München Irene de Jong, University of Amsterdam Bernhard Kytzler, University of Natal, Durban John Morgan, University of Wales, Swansea Ruurd Nauta, University of Groningen Rudi van der Paardt, University of Leiden Costas Panayotakis, University of Glasgow Stelios Panayotakis, University of Groningen Judith Perkins, Saint Joseph College, West Hartford Bryan Reardon, Professor Emeritus of Classics, University of California, Irvine James Tatum, Dartmouth College, Hanover, New Hampshire Alfons Wouters, University of Leuven Subscriptions Barkhuis Publishing Zuurstukken 37 9761 KP Eelde the Netherlands Tel. +31 50 3080936 Fax +31 50 3080934 [email protected] www.ancientnarrative.com The Recollections of Encolpius The Satyrica of Petronius as Milesian Fiction Gottskálk Jensson BARKHUIS PUBLISHING & GRONINGEN UNIVERSITY LIBRARY GRONINGEN 2004 Bókin er tileinkuð -

Renaissance Receptions of Ovid's Tristia Dissertation

RENAISSANCE RECEPTIONS OF OVID’S TRISTIA DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Gabriel Fuchs, M.A. Graduate Program in Greek and Latin The Ohio State University 2013 Dissertation Committee: Frank T. Coulson, Advisor Benjamin Acosta-Hughes Tom Hawkins Copyright by Gabriel Fuchs 2013 ABSTRACT This study examines two facets of the reception of Ovid’s Tristia in the 16th century: its commentary tradition and its adaptation by Latin poets. It lays the groundwork for a more comprehensive study of the Renaissance reception of the Tristia by providing a scholarly platform where there was none before (particularly with regard to the unedited, unpublished commentary tradition), and offers literary case studies of poetic postscripts to Ovid’s Tristia in order to explore the wider impact of Ovid’s exilic imaginary in 16th-century Europe. After a brief introduction, the second chapter introduces the three major commentaries on the Tristia printed in the Renaissance: those of Bartolomaeus Merula (published 1499, Venice), Veit Amerbach (1549, Basel), and Hecules Ciofanus (1581, Antwerp) and analyzes their various contexts, styles, and approaches to the text. The third chapter shows the commentators at work, presenting a more focused look at how these commentators apply their differing methods to the same selection of the Tristia, namely Book 2. These two chapters combine to demonstrate how commentary on the Tristia developed over the course of the 16th century: it begins from an encyclopedic approach, becomes focused on rhetoric, and is later aimed at textual criticism, presenting a trajectory that ii becomes increasingly focused and philological. -

THE CONTRAPOSITION BETWEEN EPOS and EPULLION in HELLENISTIC POETRY: STATUS QUAESTIONIS 1 José Antonio Clúa Serena

Anuario de Estudios Filológicos, ISSN 0210-8178, vol. XXVII, 23-39 THE CONTRAPOSITION BETWEEN EPOS AND EPULLION IN HELLENISTIC POETRY: STATUS QUAESTIONIS 1 José Antonio Clúa Serena Universidad de Extremadura Resumen En este artículo se esbozan algunos de los hitos más importantes que configuran, desde Antímaco de Colofón hasta las últimas manifestaciones poéticas helenísticas y romanas, la contraposición entre el e[po~ y el ejpuvllion. Sobre este último «género», repleto de elemen- tos etiológicos y largas digresiones, se aportan y se comparan datos importantes mediante dos métodos conocidos: la Quellensforchung y la comparación entre seguidores de la escuela de Calímaco y los denominados Telquines. Se analizan epigramas concretos, epilios de Teócrito, Mosco, la Hécale de Calímaco, epilios de Trifiodoro, Hedilo, Museo, Euforión, Partenio, Poliano, así como de Cornelio Galo y Cinna. Finalmente, se estudia la dicotomía «agua»/«vino» como símbolos de inspiración y se ofrece una posible clave para focalizar el paso de dicha contraposición desde la literatura helenística griega a la romana. Palabras clave: Epos, epyllion, hellenistic poetry, Cantores Callimachi. Abstract This paper describes some highly important aspects than configure, from Aminachus of Colofos to the latest Hellenistic and Roman poetic pieces, the contraposition of the concepts e[po~ and ejpuvllion. About this latter ‘genre’, filled with etiological and disgressive elements, data are contrasted according to two well known methods: Quellensforchung and comparison between Callimachus’ followers and Telquines. Specific epigrams are reviewed, also some epic poems by Theocritus, Moscos, the Hecale by Callimachus, epic poems by Trifiodorus, Hedilus, Museus, Euforius, Partenius, Polianus, Cornelius, Galius, and Cinnas. Finally, dichotomous elements like ‘water’/‘wine’ are studied as symbols for inspiration. -

Indo-European Linguistics: an Introduction Indo-European Linguistics an Introduction

This page intentionally left blank Indo-European Linguistics The Indo-European language family comprises several hun- dred languages and dialects, including most of those spoken in Europe, and south, south-west and central Asia. Spoken by an estimated 3 billion people, it has the largest number of native speakers in the world today. This textbook provides an accessible introduction to the study of the Indo-European proto-language. It clearly sets out the methods for relating the languages to one another, presents an engaging discussion of the current debates and controversies concerning their clas- sification, and offers sample problems and suggestions for how to solve them. Complete with a comprehensive glossary, almost 100 tables in which language data and examples are clearly laid out, suggestions for further reading, discussion points and a range of exercises, this text will be an essential toolkit for all those studying historical linguistics, language typology and the Indo-European proto-language for the first time. james clackson is Senior Lecturer in the Faculty of Classics, University of Cambridge, and is Fellow and Direc- tor of Studies, Jesus College, University of Cambridge. His previous books include The Linguistic Relationship between Armenian and Greek (1994) and Indo-European Word For- mation (co-edited with Birgit Anette Olson, 2004). CAMBRIDGE TEXTBOOKS IN LINGUISTICS General editors: p. austin, j. bresnan, b. comrie, s. crain, w. dressler, c. ewen, r. lass, d. lightfoot, k. rice, i. roberts, s. romaine, n. v. smith Indo-European Linguistics An Introduction In this series: j. allwood, l.-g. anderson and o.¨ dahl Logic in Linguistics d. -

Poros E Penia: Privação Ou Ambivalência Do Amor?

desígnio 9 jul.2012 POROS E PENIA: PRIVAÇÃO OU AMBIVALÊNCIA DO AMOR? Juliano Paccos Caram* CARAM, J. P. (2012). “Poros e Penia: privação ou ambivalência do amor?”. Archai n. 9, jul-dez 2012, pp. 107-116. RESUMO: Ao longo da leitura do Simpósio de Platão, é pos- * Professor de História Introdução da Filosofia Antiga na sível compreender a estreita relação entre o apetite (ἐπιθυμία) Universidade Federal da e o amor (ἔρως), enquanto este se manifesta, em última Fronteira Sul (UFFS), No âmbito da discussão acerca da genealogia campus Chapecó, Santa instância, como um apetite de imortalidade (ἐπιθυμία τῆς Catarina, Brasil. Doutorando e fisiologia do amor (ἔρως), a partir do passo 203a8 em Filosofia Antiga pela ἀθανασίας). Entretanto, este mesmo amor, que potencializa a do Simpósio de Platão, a sacerdotisa de Mantinéia, Universidade Federal de alma na descoberta do belo em si mesmo (τὸ καλόν), também Minas Gerais (UFMG). Diotima, apresenta a Sócrates uma alegoria, na qual pode aprisionar o homem na sedução do sensível, levando-o a discorre acerca da origem não somente do amor crer que nada é mais real do que a experiência amorosa pura e (ἔρως) como também do apetite (ἐπιθυμία) que simples que se esgota na apreciação de um belo corpo. o engendra. Utilizando as próprias palavras de Só- É, pois, nessa tensão entre as coisas físicas e aquelas crates, a pergunta que se coloca, a respeito do amor, verdades eternas que as sustentam que se inscreve a ambiva- é a seguinte: quem é seu pai e sua mãe? (πατρὸς lência de eros. Nossa análise pretende, através de uma leitura δέ […] τίνος ἐστὶ καὶ μητρός;) [Smp. -

And Type the TITLE of YOUR WORK in All Caps

IN CORPUS CORPORE TOTO: MERGING BODIES IN OVID’S METAMORPHOSES by JACLYN RENE FRIEND (Under the Direction of Sarah Spence) ABSTRACT Though Ovid presents readers of his Metamorphoses with countless episodes of lovers uniting in a temporary physical closeness, some of his characters find themselves so affected by their love that they become inseparably merged with the ones they desire. These scenarios of “merging bodies” recall Lucretius’ explanations of love in De Rerum Natura (IV.1030-1287) and Aristophanes’ speech on love from Plato’s Symposium (189c2-193d5). In this thesis, I examine specific episodes of merging bodies in the Metamorphoses and explore the verbal and conceptual parallels that intertextually connect these episodes with De Rerum Natura and the Symposium. I focus on Ovid’s stories of Narcissus (III.339-510), Pyramus and Thisbe (IV.55-166), Salmacis and Hermaphroditus (IV.276-388), and Baucis and Philemon (VIII.611-724). I also discuss Ovid’s “merging bodies” in terms of his ideas about poetic immortality. Finally, I consider whether ancient representations of Narcissus in the visual arts are indicative of Ovid’s poetic success in antiquity. INDEX WORDS: Ovid, Metamorphoses, Intertextuality, Lucretius, De Rerum Natura, Plato, Symposium, Narcissus, Pyramus, Thisbe, Salmacis, Hermaphroditus, Baucis, Philemon, Corpora, Immortality, Pompeii IN CORPUS CORPORE TOTO: MERGING BODIES IN OVID’S METAMORPHOSES by JACLYN RENE FRIEND B.A., Denison University, 2012 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF ARTS ATHENS, GEORGIA 2014 © 2014 Jaclyn Rene Friend All Rights Reserved IN CORPUS CORPORE TOTO: MERGING BODIES IN OVID’S METAMORPHOSES by JACLYN RENE FRIEND Major Professor: Sarah Spence Committee: Mark Abbe Naomi Norman Electronic Version Approved: Maureen Grasso Dean of the Graduate School The University of Georgia May 2014 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank Dr.