Development of Energy Sector in Iran in Light of Energy Trilemma. an Analysis of Legal and Policy Challenges

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Payandan Shareholders

PAYANDAN PAYANDAN 1. Company Background Creative Path to Growth Payandan Shareholders PAYANDAN Payandan’s shares belong to Mostazafan Foundation of Islamic Revolution. • Mostazafan Foundation owns 49% • Sina Energy Development Company owns 51% Mostazafan Foundation of Islamic Revolution Sina Energy Development Company PAYANDAN Mostazafan Foundation of Islamic Revolution PAYANDAN SEDCO Sina Financial Paya Saman Pars (Oil & Gas) & Investment Co (Road & Building) Sina Food Industries Iran Housing Group Saba Paya Sanat Sina (Power & Electricity) (Tire, Tiles, Glasswork, Textile, Etc) Ferdos Pars Sina ICT Group (Agriculture) Parsian Tourism Kaveh Pars & Transport Group (Mining) Alavi Foundation Alavi Civil (Charitable) Engineering Group Sina Energy Development Holding Company PAYANDAN SEDCO as one of subsidiaries of The Mostazafan Foundation of Islamic Revolution is considered one of pioneer holding companies in area of oil & gas which aims on huge projects in whole chains of oil and gas. Payandan (Oil & Gas General Contractor) North Drilling (Offshore Drilling) Pedex (Onshore Drilling) Behran (Oil Refinery Co) Dr Bagheri SEDCO Managing Director Coke Waste Water Refining Co Payandan in Numbers PAYANDAN +40 1974 Years ESTABLISHED +1400 +4000 EMPLOYEES CONTRACTOR +200,000,000 $ ANNUAL TURNOVER 75 COMPLETED PROJECTS Company Background PAYANDAN • 48” Zanjan-Mianeh Pipeline • 56” Saveh-Loushan • South Pars – SP No. 14 Pipeline (190KM) • South Pars – SP No. 13 • 56" Dezfoul- Kouhdasht Pipeline (160KM) 1974 1996 2003 2005 2007 2009 2011 2013 2015 2017 • Nargesi Gas • F & G Lavan • 56” Asaluyeh Gathering & • South Pars – SP Pipeline Injection No. 17 & 18 • 30” Iran- Payandan is • South Pars – SP No. 22,23,24 Armenia established (oil and • 48” Iraq Pipeline Naftkhane- Pipeline gas contractor) Baghdad (63KM) (113KM) • 56” Naeen-Tehran Gas Pipeline (133KM) • Parsian Gas Refinery • 56” Loushan-Rasht Gas Pipeline (81KM) • Pars Petrochemical Port • Arak Shazand Refinery • Kangan Gas Compressor Station • South Pars – SP No. -

The Relationship Between Inflation Rate, Oil Revenue and Taxation In

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by International Institute for Science, Technology and Education (IISTE): E-Journals Journal of Economics and Sustainable Development www.iiste.org ISSN 2222-1700 (Paper) ISSN 2222-2855 (Online) Vol.4, No.19, 2013 The Relationship between Inflation Rate, Oil Revenue and Taxation in IRAN: Based OLS Methodology Kamyar Radnia Economics Department, School of Social Science, Universiti Sains Malaysia (U.S.M), Paulu Pinang 11800, Malaysia *Email: [email protected] Abstract In this paper we investigate the relationship between inflation behaviors relying to using oil revenue and taxation revenue as two distinguish original sources in Iranian economy. We employ the Ordinary Least Square (OLS) as methods for analysis data in short and long run periods. In this study, we found that the oil revenue and corporate tax are significant variables to measurement of consumer price index. Taxation has both positive and negative impact in economic growth and consumer price index due to increasing and decreasing inflation rate. Since increase export oil cause to increasing in price level in Iran, government ought to try to allocate the earning from selling of oil. On the other side, increasing in corporate tax cause to price level rises. So, policy makers and economics should reduces taxation on corporate to make incentive in investors to more investment. Key Words: Microeconomic variables, Inflation rate, Taxation, OLS Methodology, Iranian economy 1. Introduction The history of oil exploration and extraction dates back a long time ago, especially for Iran. The base of the Iranian economy has been placed on the extraction of natural resources. -

Health Sector Evolution Plan in Iran; Equity and Sustainability Concerns

http://ijhpm.com Int J Health Policy Manag 2015, 4(10), 637–640 doi 10.15171/ijhpm.2015.160 Editorial Health Sector Evolution Plan in Iran; Equity and Sustainability Concerns Maziar Moradi-Lakeh1,2*, Abbas Vosoogh-Moghaddam3,4 Abstract Article History: In 2014, a series of reforms, called as the Health Sector Evolution Plan (HSEP), was launched in the health system of Received: 22 May 2015 Iran in a stepwise process. HSEP was mainly based on the fifth 5-year health development national strategies (2011- Accepted: 27 August 2015 2016). It included different interventions to: increase population coverage of basic health insurance, increase quality ePublished: 31 August 2015 of care in the Ministry of Health and Medical Education (MoHME) affiliated hospitals, reduce out-of-pocket (OOP) payments for inpatient services, increase quality of primary healthcare, launch updated relative value units (RVUs) of clinical services, and update tariffs to more realistic values. The reforms resulted in extensive social reaction and different professional feedback. The official monitoring program shows general public satisfaction. However, there are some concerns for sustainability of the programs and equity of financing. Securing financial sources and fairness of the financial contribution to the new programs are the main concerns of policy-makers. Healthcare providers’ concerns (as powerful and influential stakeholders) potentially threat the sustainability and efficiency of HSEP. Previous experiences on extending health insurance coverage show that they can lead to a regressive healthcare financing and threat financial equity. To secure financial sources and to increase fairness, the contributions of people to new interventions should be progressive by their income and wealth. -

Geopolitics of the Iranian Nuclear Energy Program

Geopolitics of the Iranian Nuclear Energy Program But Oil and Gas Still Matter CENTER FOR STRATEGIC & CSIS INTERNATIONAL STUDIES A Report of the CSIS Energy and National Security Program 1800 K Street, NW | Washington, DC 20006 author Tel: (202) 887-0200 | Fax: (202) 775-3199 Robert E. Ebel E-mail: [email protected] | Web: www.csis.org March 2010 ISBN 978-0-89206-600-1 CENTER FOR STRATEGIC & Ë|xHSKITCy066001zv*:+:!:+:! CSIS INTERNATIONAL STUDIES Geopolitics of the Iranian Nuclear Energy Program But Oil and Gas Still Matter A Report of the CSIS Energy and National Security Program author Robert E. Ebel March 2010 About CSIS In an era of ever-changing global opportunities and challenges, the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) provides strategic insights and practical policy solutions to decision- makers. CSIS conducts research and analysis and develops policy initiatives that look into the future and anticipate change. Founded by David M. Abshire and Admiral Arleigh Burke at the height of the Cold War, CSIS was dedicated to the simple but urgent goal of finding ways for America to survive as a nation and prosper as a people. Since 1962, CSIS has grown to become one of the world’s preeminent public policy institutions. Today, CSIS is a bipartisan, nonprofit organization headquartered in Washington, D.C. More than 220 full-time staff and a large network of affiliated scholars focus their expertise on defense and security; on the world’s regions and the unique challenges inherent to them; and on the issues that know no boundary in an increasingly connected world. -

Wind and Solar Energy Developments in Iran

WIND AND SOLAR ENERGY DEVELOPMENTS IN IRAN H. Kazemi Karegara,b, A.Zahedia,V. Ohisa, G. taleghanib and M. Khalajib aDepartment of Electrical & Computer Systems Engineering, PO Box 35, Monash University, Victoria 3800 bCentre of Renewable Energy Research and Application, North Amir Abad, Tehran/Iran Abstract This paper presents the potential for wind and solar energy in Iran and shows how much electric energy is now produced by renewable power plants compared to steam and gas. The importance of renewable energy effects on Iran’s environment and economy is also discussed and the issue of the contribution of renewable energy for producing electricity in the future will be shown. Also this paper highlights the ability of Iran to manufacture the components of the wind turbine and solar system locally, and its effect on the price of wind turbine and solar energy. Key Words: Renewable Energy, Wind Turbine, Solar Energy 1. INTRODUCTION 2. RENEWABLE ENERGY MOTIVATION IN IRAN Iran is known as the second largest oil production member in Organization of Petrol Export Country (OPEC) with The necessity of renewable energy in Iran can be categorized production near 3.5 million barrel oil per day and accounts in two main issues: a) Environmental pollution and b) More for roughly 5% of global oil outputs. Also, Iran contains an oil and gas export. estimated 812 Trillion Cubic Feet (TFC) in proven natural gas reserves, surpassed only by Russia in the world [1]. As mentioned before, the most important environmental problem that Iran faces is air pollution. Since 1980, carbon Electric power generation installed in Iran is about 32.5 Giga emission in Iran has increased 240% from 33.1 million Watts (GW) with more than 87% being from thermal natural metric tons to 79.4 million metric tons in 1998 [3] and is still gas fired power plant. -

Worldwide Estate and Inheritance Tax Guide

Worldwide Estate and Inheritance Tax Guide 2021 Preface he Worldwide Estate and Inheritance trusts and foundations, settlements, Tax Guide 2021 (WEITG) is succession, statutory and forced heirship, published by the EY Private Client matrimonial regimes, testamentary Services network, which comprises documents and intestacy rules, and estate Tprofessionals from EY member tax treaty partners. The “Inheritance and firms. gift taxes at a glance” table on page 490 The 2021 edition summarizes the gift, highlights inheritance and gift taxes in all estate and inheritance tax systems 44 jurisdictions and territories. and describes wealth transfer planning For the reader’s reference, the names and considerations in 44 jurisdictions and symbols of the foreign currencies that are territories. It is relevant to the owners of mentioned in the guide are listed at the end family businesses and private companies, of the publication. managers of private capital enterprises, This publication should not be regarded executives of multinational companies and as offering a complete explanation of the other entrepreneurial and internationally tax matters referred to and is subject to mobile high-net-worth individuals. changes in the law and other applicable The content is based on information current rules. Local publications of a more detailed as of February 2021, unless otherwise nature are frequently available. Readers indicated in the text of the chapter. are advised to consult their local EY professionals for further information. Tax information The WEITG is published alongside three The chapters in the WEITG provide companion guides on broad-based taxes: information on the taxation of the the Worldwide Corporate Tax Guide, the accumulation and transfer of wealth (e.g., Worldwide Personal Tax and Immigration by gift, trust, bequest or inheritance) in Guide and the Worldwide VAT, GST and each jurisdiction, including sections on Sales Tax Guide. -

Mayors for Peace Member Cities 2021/10/01 平和首長会議 加盟都市リスト

Mayors for Peace Member Cities 2021/10/01 平和首長会議 加盟都市リスト ● Asia 4 Bangladesh 7 China アジア バングラデシュ 中国 1 Afghanistan 9 Khulna 6 Hangzhou アフガニスタン クルナ 杭州(ハンチォウ) 1 Herat 10 Kotwalipara 7 Wuhan ヘラート コタリパラ 武漢(ウハン) 2 Kabul 11 Meherpur 8 Cyprus カブール メヘルプール キプロス 3 Nili 12 Moulvibazar 1 Aglantzia ニリ モウロビバザール アグランツィア 2 Armenia 13 Narayanganj 2 Ammochostos (Famagusta) アルメニア ナラヤンガンジ アモコストス(ファマグスタ) 1 Yerevan 14 Narsingdi 3 Kyrenia エレバン ナールシンジ キレニア 3 Azerbaijan 15 Noapara 4 Kythrea アゼルバイジャン ノアパラ キシレア 1 Agdam 16 Patuakhali 5 Morphou アグダム(県) パトゥアカリ モルフー 2 Fuzuli 17 Rajshahi 9 Georgia フュズリ(県) ラージシャヒ ジョージア 3 Gubadli 18 Rangpur 1 Kutaisi クバドリ(県) ラングプール クタイシ 4 Jabrail Region 19 Swarupkati 2 Tbilisi ジャブライル(県) サルプカティ トビリシ 5 Kalbajar 20 Sylhet 10 India カルバジャル(県) シルヘット インド 6 Khocali 21 Tangail 1 Ahmedabad ホジャリ(県) タンガイル アーメダバード 7 Khojavend 22 Tongi 2 Bhopal ホジャヴェンド(県) トンギ ボパール 8 Lachin 5 Bhutan 3 Chandernagore ラチン(県) ブータン チャンダルナゴール 9 Shusha Region 1 Thimphu 4 Chandigarh シュシャ(県) ティンプー チャンディーガル 10 Zangilan Region 6 Cambodia 5 Chennai ザンギラン(県) カンボジア チェンナイ 4 Bangladesh 1 Ba Phnom 6 Cochin バングラデシュ バプノム コーチ(コーチン) 1 Bera 2 Phnom Penh 7 Delhi ベラ プノンペン デリー 2 Chapai Nawabganj 3 Siem Reap Province 8 Imphal チャパイ・ナワブガンジ シェムリアップ州 インパール 3 Chittagong 7 China 9 Kolkata チッタゴン 中国 コルカタ 4 Comilla 1 Beijing 10 Lucknow コミラ 北京(ペイチン) ラクノウ 5 Cox's Bazar 2 Chengdu 11 Mallappuzhassery コックスバザール 成都(チォントゥ) マラパザーサリー 6 Dhaka 3 Chongqing 12 Meerut ダッカ 重慶(チョンチン) メーラト 7 Gazipur 4 Dalian 13 Mumbai (Bombay) ガジプール 大連(タァリィェン) ムンバイ(旧ボンベイ) 8 Gopalpur 5 Fuzhou 14 Nagpur ゴパルプール 福州(フゥチォウ) ナーグプル 1/108 Pages -

The Imperial Frontier: Tribal Dynamics and Oil in Qajar Persia, 1901-1910

The Imperial Frontier: Tribal Dynamics and Oil in Qajar Persia, 1901-1910 Melinda Cohoon A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in International Studies: Middle East University of Washington 2017 Committee: Arbella Bet-Shlimon Ellis Goldberg Program Authorized to Offer Degree: The Henry M. Jackson School of International Studies ©Copyright 2017 Melinda Cohoon University of Washington Abstract The Imperial Frontier: Tribal Dynamics and Oil in Qajar Persia, 1901-1910 Melinda Cohoon Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Assistant Professor Arbella Bet-Shlimon Department of History By using the Political Diaries of the Persian Gulf, I elucidate the complex tribal dynamics of the Bakhtiyari and the Arab tribes of the Khuzestan province during the early twentieth century. Particularly, these tribes were by and large influenced by the oil prospecting and drilling under the D’Arcy Oil Syndicate. My research questions concern: how the Bakhtiyari and Arab tribes were impacted by the British Oil Syndicate exploration into their territory, what the tribal affiliations with Britain and the Oil Syndicate were, and how these political dynamics changed for tribes after oil was discovered at Masjid-i Suleiman. The Oil Syndicate initially received a concession from the Qajar government, but relied much more so on tribal accommodations and treaties. In addressing my research questions, I have found that there was a contention between the Bakhtiyari and the British company, and a diplomatic relationship with Sheikh Khazal of Mohammerah (or today’s Khorramshahr) and Britain. By relying on Sheikh Khazal’s diplomatic skills with the Bakhtiyari tribe, the British Oil Syndicate penetrated further into the southwest Persia, up towards Bakhtiyari territory. -

Working Paper 442 November 2016

Fiscal Policy, Inequality and Poverty in Iran: Assessing the Impact and Effectiveness of Taxes and Transfers the Poor in the Developing World Ali Enami, Nora Lustig, and Alireza Taqdiri Abstract Using the Iranian Household Expenditure and Income Survey (HEIS) for 2011/12, we apply the marginal contribution approach to determine the impact and effectiveness of each fiscal intervention, and the fiscal system as a whole, on inequality and poverty. Net direct and indirect taxes combined reduce the Gini coefficient by 0.0644 points and the headcount ratio by 61 percent. When the monetized value of in-kind benefits in education and health are included, the reduction in inequality is 0.0919 Gini points. Based on the magnitudes of the marginal contributions, we find that the main driver of these reductions is the Targeted Subsidy Program, a universal cash transfer program implemented in 2010 to compensate individuals for the elimination of energy subsidies. The main reduction in poverty occurs in rural areas, where the headcount ratio declines from 44 to 23 percent. In urban areas, fiscally-induced poverty reduction is more modest: the headcount ratio declines from 13 to 5 percent. Taxes and transfers are similar in their effectiveness in achieving their inequality-reducing potential. By achieving 40 percent of its inequality-reducing potential, the income tax is the most effective intervention on the revenue side. On the spending side, Social Assistance transfers are the most effective and they achieve 45 percent of their potential. Taxes are especially effective in raising revenue without causing poverty to rise, indicating that the poor are largely spared from being taxed. -

A Review on Energy and Renewable Energy Policies in Iran

sustainability Review A Review on Energy and Renewable Energy Policies in Iran Saeed Solaymani Department of Economics, Faculty of Administration and Economics, Arak University, Arak 38156879, Iran; [email protected] or [email protected]; Tel.: +98-8632621000 Abstract: Iran, endowed with abundant renewable and non-renewable energy resources, particularly non-renewable resources, faces challenges such as air pollution, climate change and energy security. As a leading exporter and consumer of fossil fuels, it is also attempting to use renewable energy as part of its energy mix toward energy security and sustainability. Due to its favorable geographic char- acteristics, Iran has diverse and accessible renewable sources, which provide appropriate substitutes to reduce dependence on fossil fuels. Therefore, this study aims to examine trends in energy demand, policies and development of renewable energies and the causal relationship between renewable and non-renewable energies and economic growth using two methodologies. This study first reviews the current state of energy and energy policies and then employs Granger causality analysis to test the relationships between the variables considered. Results showed that renewable energy technologies currently do not have a significant and adequate role in the energy supply of Iran. To encourage the use of renewable energy, especially in electricity production, fuel diversification policies and development program goals were introduced in the late 2000s and early 2010s. Diversifying energy resources is a key pillar of Iran’s new plan. In addition to solar and hydropower, biomass from the municipal waste from large cities and other agricultural products, including fruits, can be used to generate energy and renewable sources. -

Petroleum: an Engine for Global Development

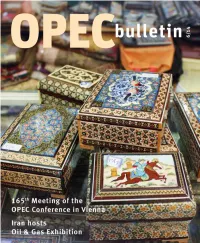

OPEC th International Seminar Petroleum: An Engine for Global Development 3–4 June 2015 Hofburg Palace Vienna, Austria www.opec.org Reasons to be cheerful It was over quite quickly. In fact, the 165th Meeting whilst global oil demand was expected to rise from of the OPEC Conference finished two hours ahead of 90m b/d to 91.1m b/d over the same period. In ad- Commentary schedule. Even the customary press conference, held dition, petroleum stock levels, in terms of days of for- immediately after the Meeting at the Organization’s ward demand cover, remained comfortable. “These Secretariat in Vienna, Austria on June 11 and usually numbers make it clear that the oil market is stable and a busy affair, was most probably completed in record balanced, with adequate supply meeting the steady time. But this brevity of discourse spelled good news growth in demand,” OPEC Conference President, Omar — for OPEC and, in fact, all petroleum industry stake- Ali ElShakmak, Libya’s Acting Oil and Gas Minister, holders. As the much-heralded saying goes — ‘don’t be said in his opening address to the Conference. tempted to tamper with a smooth-running engine’. And Of course, there are still downside risks to the glob- that is exactly what OPEC’s Oil and Energy Ministers al economy, both in the OECD and non-OECD regions, did during their customary mid-year Meeting. They de- and there is continuing concern over some production cided to leave the Organization’s 30 million barrels/ limitations, but with non-OPEC supply growth of 1.4m day oil production ceiling in place and unchanged for b/d forecast over the next year, in general, things are the remainder of 2014. -

In the Name of God Development of Yadavaran Oilfield Moving On/ 26 China's Colorful Presence in Iran's Petroleum Industry

Oct . 2009 - 119 In The Name of God INDEX OCT. 2009 / No.119 Articles on Oil & Gas in the English section, in cooperation with IranOilGas.com Published by: IRANIAN ASSO - CIATION FOR ENERGY ECO-NOMICS (IRAEE) ISSN 1563-1133 Rivalries in the Area of Natural Gas; An Director and Editor-in - Chief: Engin Propelling Political Developments / 2 Seyed Gholamhossein Hassantash Editorial Manager: Homayoun Mobaraki Challenges Facing Iran’s Petroleum Industry / 6 Editorial Board: Majid Abbaspour, Reza Farmand, Ali Moshtaghian, Mohammad-reza Omidkhah, Ebrahim Bagherzadeh, Fereidoun Barkeshly, Hassan Khosravizadeh, China’s Oil Needs Affect its Iran Ties / 7 Mohammad-ali Movahhed, Behroz Beik Alizadeh, Ali Emami Meibodi, Seyed Mohammad-ali Tabatabaei, Afshin Javan, Hamid Abrishami, Mohammad-bagher Heshmatzadeh, Mehdi Nematollahi, Mozafar Jarrahi, Ali / 8 Shams Ardakani, Mohammad Mazreati Layout : Adamiyat Advertising Agency Iran Ranks First in the Middle East in Terms Advertisement Dept : of Transport of Gas / 11 Adamiyat Advertising Agency Tel: 021 - 88 96 12 15 - 16 Energy Intensity Reduction Potentials in OPEC and Its Advantages / 11 Translators: Mahyar Emami, Hamid Barimani Subscription: Hamideh Noori Development of Yadavaran Oilfield Moving on / 26 IRANIAN ASSOCIATION FOR ENERGY ECONOMICS China’s Colorful Presence in Iran’s Petroleum Unit 13, Fourth flour, No.177, Vahid Dastgerdi (Zafar) Ave., Tehran, Iran Tel: (9821) 22262061-3 Industry / 27 Fax: (9821) 22262064 Web: www.IRAEE.org E-mail: [email protected] 1 Oct . 2009 - 119 Rivalries in the