Brisbois Ou 0169D 10837.Pdf (847.7Kb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Article

International Conference on Arts, Design and Contemporary Education (ICADCE 2016) The Concertizing Clarinet in the Music of the 20th- 21st Centuries Yu Zhao Department of Musical Upbringing and Education Institute of Music, Theatre and Choreography Herzen State Pedagogical University of Russia Saint-Petersburg, Russia E-mail: [email protected] Abstract—The article deals with stating the problem of a clarinet concert of the 20-21 centuries (one should note in research in ontology of the genre of Clarinet Concert in 20-21 this regard S. E. Artemyev‟s full-featured thesis considering centuries. The author identifies genre variants of long forms the Concerto for clarinet and orchestra of the 18th century). for solo clarinet with orchestra or instrumental ensemble and proposes further steps in making such a research, as well. II. A SHORT GUIDE IN THE HISTORY OF THE CLARINET Keywords—instrumental concert; concertizing; concerto; CONCERT GENRE concert genres; genre diversity Studies in the executive mastership are connected with a research of the evolution of the genres of instrumental music. I. INTRODUCTION The initial period of genesis and development of clarinet concert is investigated widely. Contemporary music in its various genres has become in many aspects a subject of scrupulous studies in musicology. It is known that the most early is the composition of Our research deals with professional problematics of the Antonio Paganelli indicated by the author as Concerto per instrumental concert genre, viewed more narrowly, namely, Clareto (1733). Possibly, it was written for chalumeau, the connected with clarinet performance. instrument-predecessor of the clarinet itself. But, before this time clarinet was used as one of the concertizing instruments The purpose of this article is to identify the situation in the genre of Concerto Grosso, particularly by J. -

Heralding a New Enlightenment

Peculiarities of Clarinet Concertos Form-Building in the Second Half of the 20th Century and the Beginning of the 21st Century Marina Chernaya and Yu Zhao* Abstract: The article deals with clarinet concertos composed in the 20th– 21st centuries. Many different works have been created, either in one or few parts; the longest concert that is mentioned has seven parts (by K. Meyer, 2000). Most of the concertos have 3 parts and the fast-slowly-fast kind of structure connected with the Italian overture; sometimes, the scheme has variants. Our question is: How does the concerto genre function during this period? To answer, we had to search many musical compositions. Sometimes the clarinet is accompanied by orchestra, other times it is surrounded by an ensemble of instruments. More than 100 concertos were found and analyzed. Examples of such concertos were written by C. Nielsen, P. Boulez, J. Adams, C. Debussy, M. Arnold, A. Copland, P. Hindemith, I. Stravinsky, S. Vassilenko, and the attention in the article is focused on them. A special complete analysis is made as regards “Domaines” for clarinet and 21 instruments divided in 6 groups, by Pierre Boulez that had a great role for the concert routine, based on the “aleatoric” principle. The conclusions underline the significant development of the clarinet concerto genre in the 20th -21st centuries, the high diversity of the compositions’ structures, the considerable expressiveness and technicality together with the soloist’s part in the expressive concertizing (as a rule). Further studies suggest the analysis of stylistic and structural peculiarities of the found compositions that are apparently to win their popularity with performers and listeners. -

The Clarinet World

REVIEWS AUDIO NOTES by Kip Franklin Milton Babbit’s Composition for Four undauntedly masters the rapidly cascading Instruments begins with an extended arpeggios in the scherzando section and Stanley Drucker is unquestionably a titan clarinet passage that Drucker performs conveys control and color in the more of the clarinet world. In addition to his six in an improvisational off-the-cuff lyrical passages. This orchestration is decades with the New York Philharmonic manner. The work features a variety of a refreshing departure from the more (nearly five of them as principal clarinet), instrumental timbres and techniques, traditional clarinet and piano version. his career entails many commissions and resulting in a unique tapestry that Like Nature Moods and Contrasts, recordings. A new double-disc set, Stanley resembles the pointillistic writings of Weigl’s New England Suite showcases Drucker: Heritage Collection 6-7, Webern and Boulez. Valley Weigl’s Nature Drucker’s aptitude as a chamber musician. contains recordings of Drucker playing Moods ensues, with Drucker showcasing Her writing allows each instrument solo many of the most colossal works in the his ability to emulate the human voice. passages while still creating interwoven repertoire, as well as many important and Each of the five movements in this work and complex ensemble textures. Drucker’s rarely-played or obscure smaller works conveys a bucolic ambience with perfectly mellow, deep tone makes this an spanning the entirety of his career. That interwoven counterpoint between the especially memorable piece; at times it Drucker is on display as both a soloist clarinet, voice and violin. The balance in is contemplative and ponderous, and at and chamber musician throughout this this particular work is exceptional, with others jubilant and capricious. -

Courtesy of Eric Nelson, As Posted on Klarinet, 9 and 11 Feb 1997. Eric Nelson Is Clarinetist with the Lightwood Duo, an Actively Touring Clarinet/Guitar Duo

Courtesy of Eric Nelson, as posted on Klarinet, 9 and 11 Feb 1997. Eric Nelson is clarinetist with The Lightwood Duo, an actively touring clarinet/guitar duo. Their CDs are available through their website, http://www.lightwoodduo.com. About two weeks ago, there were some questions about Aage Oxenvad on the list. Having studied Nielsen and clarinet at the Royal Conservatory in Copenhagen [in 1979], I would like to pass on some first-hand information on Oxenvad. There are two major obstacles to acquiring accurate information about Danish music. First, much of the info exists only in the Danish language; not exactly a familiar language to most. Second, the Danes are not inclined to value the sharing of such information. To quote Tage Scharff, the clarinet professor with whom I studied: "You Americans [and English as well] love to get together and give lectures, deliver papers, and hold conferences. Here in Denmark, vi spiller! [we PLAY]". He was quite amused that I, a performing clarinetist, would be so interested in such material. On a posting on this list, Jarle Brosveet wrote: "In the first place Oxenvad did not inspire Nielsen to write the concerto, although he was the first to perform it. It was written at the request of Nielsen's benefactor and one-time student Carl Johan Michaelsen. Second, Oxenvad, who is described as a choleric, made this unflattering remark about Nielsen and the concerto: "He must be able to play the clarinet himself, otherwise the would hardly have been able to find the worst notes to play." Oxenvad performed it on several occasions with no apparent success although he reportedly did all he could, whatever that is supposed to mean. -

Download the Clarinet Saxophone Classics Catalogue

CATALOGUE 2017 www.samekmusic.com Founded in 1992 by acclaimed clarinetist Victoria Soames Samek, Clarinet & Saxophone Classics celebrates the single reed in all its richness and diversity. It’s a unique specialist label devoted to releasing top quality recordings by the finest artists of today on modern and period instruments, as well as sympathetically restored historical recordings of great figures from the past supported by informative notes. Having created her own brand, Samek Music, Victoria is committed to excellence through recordings, publications, learning resources and live performances. Samek Music is dedicated to the clarinet and saxophone, giving a focus for the wonderful world of the single reed. www.samek music.com For further details contact Victoria Soames Samek, Managing Director and Artistic Director Tel: + 44 (0) 20 8472 2057 • Mobile + 44 (0) 7730 987103 • [email protected] • www.samekmusic.com Central Clarinet Repertoire 1 CC0001 COPLAND: SONATA FOR CLARINET Clarinet Music by Les Six PREMIERE RECORDING Featuring the World Premiere recording of Copland’s own reworking of his Violin Sonata, this exciting disc also has the complete music for clarinet and piano of the French group known as ‘Les Six’. Aaron Copland Sonata (premiere recording); Francis Poulenc Sonata; Germaine Tailleferre Arabesque, Sonata; Arthur Honegger Sonatine; Darius Milhaud Duo Concertant, Sonatine Victoria Soames Samek clarinet, Julius Drake piano ‘Most sheerly seductive record of the year.’ THE SUNDAY TIMES CC0011 SOLOS DE CONCOURS Brought together for the first time on CD – a fascinating collection of pieces written for the final year students studying at the paris conservatoire for the Premier Prix, by some of the most prominent French composers. -

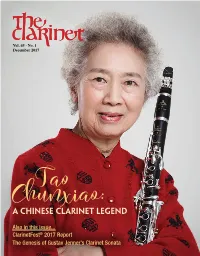

A Chinese Clarinet Legend Also in This Issue

Vol. 45 • No. 1 December 2017 Tao AChunxiao: Chinese Clarinet Legend Also in this issue... ClarinetFest® 2017 Report The Genesis of Gustav Jenner’s Clarinet Sonata D’ADDARIO GIVES ME THE FREEDOM TO PRODUCE THE SOUND I HEAR IN MY HEAD. — JONATHAN GUNN REINVENTING CRAFTSMANSHIP FOR THE 21ST CENTURY. President’sThe EDITOR Rachel Yoder [email protected] ASSOCIATE EDITOR Jessica Harrie [email protected] EDITORIAL BOARD Dear ICA Members, Mitchell Estrin, Heike Fricke, Jessica Harrie, ope you are enjoying a wonderful new season Caroline Hartig, Rachel Yoder of music making with fulflling activities and MUSIC REVIEWS EDITOR events. Many exciting things are happening in Gregory Barrett – [email protected] our organization. Te ICA believes that if you Hdo good things, good things happen! I want to thank everyone AUDIO REVIEWS EDITOR who has contributed to our Capital Campaign. We especially Chris Nichols – [email protected] wish to thank Alan and Janette Stanek for their amazing gift of $11,250.00 to fund our competitions for the coming GRAPHIC DESIGN ClarinetFest® 2018. Te ICA is grateful for your generosity Karry Tomas Graphic Design and the generosity of all Capital Campaign donors. Please [email protected] visit www.youcaring.com/internationalclarinetassociation to Caroline Hartig make your donation today. We would love to hear your story ADVERTISING COORDINATOR and look forward to our continued campaign which will last Elizabeth Crawford – [email protected] through ClarinetFest® 2018. Also, visit www.clarinet.org/ donor-wall to check out our donor wall with many photos and thank-yous to those who INDEX MANAGER contributed to the ICA for ClarinetFest® 2017. -

John M. Cipolla, Clarinetist Curriculum Vitae 1367 Rolling

John M. Cipolla Curriculum Vitae 1367 Rolling Ridge Way Bowling Green, Kentucky 42013 Office: 270-745-7093, Mobile: 270-996-9270 E-mail: [email protected] Click on this symbol throughout the CV to link to related sites or documents SelectedWorks from the WKU TopSCHOLAR Research and Creative Activity Database EDUCATION The University of North Carolina-Greensboro Greensboro, North Carolina Doctor of Musical Arts in clarinet performance 2002 • Dissertation: Linear Aspects of Harmony in the Countermelodies of New Orleans Jazz Musician, Sidney Bechet • Advisor and major professor, Dr. Kelly Burke The Mason Gross School of the Arts, Rutgers University New Brunswick, New Jersey Master of Music in clarinet performance 1987 • Major professor, Dr. George Jones The Eastman School of Music, The University of Rochester Rochester, New York Bachelor of Music in saxophone performance 1984 • Major professors Dr. Ramon Ricker, William Osseck The Juilliard School of Music New York, New York One year of study towards Bachelor of Music in saxophone performance degree 1980 • Scholarship student • Major professor, Joseph Allard ACADEMIC EMPLOYMENT HISTORY Western Kentucky University Bowling Green, Kentucky Professor of Music 2015–present Western Kentucky University Bowling Green, Kentucky Associate Professor of Music 2008–2014 Western Kentucky University Bowling Green, Kentucky Assistant Professor of Music 2002–2008 University of North Carolina at Greensboro Greensboro, North Carolina GTA, Full–Time doctoral student 2000–2002 Wagner College Staten Island, -

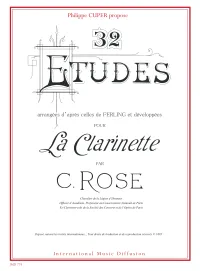

IMDIMD774.Pdf

Cyrille Chrysogone ROSE est l’un des plus célèbres Cyrille Chrysogone ROSE was one of the most famous french clarinettist. clarinettistes français. Né le 13 février 1830 à Born on february 13th 1830 in Lestrem in the north of France where the Lestrem dans la région du Nord-Pas de Calais, majority of the french clarinettists came. berceau des clarinettistes français, fils de Jean- He is the son of Jean-Baptiste ROSE and Joséphine HAVERBECQUE. Baptiste ROSE et de Joséphine HAVERBECQUE, Widowed of Sophie, he had a daughter. He lived in Paris (70 rue de veuf de Sophie, il aura une fille. Rose a longtemps Tocqueville) but he died in Meaux near Paris on June 24th 1902 in his last habité à Paris, au 70 rue de Tocqueville. Souffrant house (62 avenue de la République). de rhumatismes il décède à Meaux près de Paris le 24 juin 1902, à son domicile du 62 avenue de His principal teacher was the man who invented (with Buffet) the modern la République. clarinet : Hyacinthe Eléonore Klosé (1808-1880), professor at the Paris conservatory. Rose win his first prize in the Klosé’s class in 1847. Son principal professeur est l’inventeur (avec From 1855 to 1891 he was principal clarinet at the PARIS OPERA Buffet) de la clarinette moderne : Hyacinthe ORCHESTRA. Gounod, Massenet and some others consulted him on Eléonore KLOSÉ (1808-1880), professeur au clarinet technic.The famous aria “Ah! Pleurez mes yeux” from the Massenet conservatoire de Paris. Rose obtient son premier prix dans sa classe en 1847 puis devient première clarinette solo de opéra « Le Cid » was thought for the Rose alto clarinet. -

The Clarinet Choir Music of Russell S

Vol. 47 • No. 2 March 2020 — 2020 ICA HONORARY MEMBERS — Ani Berberian Henri Bok Deborah Chodacki Paula Corley Philippe Cuper Stanley Drucker Larry Guy Francois Houle Seunghee Lee Andrea Levine Robert Spring Charles West Michael Lowenstern Anthony McGill Ricardo Morales Clarissa Osborn Felix Peikli Milan Rericha Jonathan Russell Andrew Simon Greg Tardy Annelien Van Wauwe Michele VonHaugg Steve Williamson Yuan Yuan YaoGuang Zhai Interview with Robert Spring | Rediscovering Ferdinand Rebay Part 3 A Tribute to the Hans Zinner Company | The Clarinet Choir Music of Russell S. Howland Life Without Limits Our superb new series of Chedeville Clarinet mouthpieces are made in the USA to exacting standards from the finest material available. We are excited to now introduce the new ‘Chedeville Umbra’ and ‘Kaspar CB1’ Clarinet Barrels, the first products in our new line of high quality Clarinet Accessories. Chedeville.com President’sThe EDITOR Rachel Yoder [email protected] ASSOCIATE EDITOR Dear ICA Members, Jessica Harrie [email protected] t is once again time for the membership to vote in the EDITORIAL BOARD biennial ICA election of officers. You will find complete Mitchell Estrin, Heike Fricke, Denise Gainey, information about the slate of candidates and voting Jessica Harrie, Rachel Yoder instructions in this issue. As you may know, the ICA MUSIC REVIEWS EDITOR bylaws were amended last summer to add the new position Gregory Barrett I [email protected] of International Vice President to the Executive Board. This position was added in recognition of the ICA initiative to AUDIO REVIEWS EDITOR engage and cultivate more international membership and Kip Franklin [email protected] participation. -

Catalogue and Musik” (Degenerate Music) Opened in Documentation of Sound) Should Düsseldorf

zagreb | 2018. XVIII. SVJETSKI KONGRES SAKSOFONISTA ODRŽAVA SE POD POKROVITELJSTVOM MILANA BANDIĆA, GRADONAČELNIKA GRADA ZAGREBA | THE XVIII WSC IS HELD UNDER THE PATRONAGE OF MR MILAN BANDIĆ, MAYOR OF THE CITY OF ZAGREB gradonačelnik grada zagreba Poštovani sudionici, dragi gosti, Zagreb prvi put ugošćuje renomirani Svjetski kongres saksofonista. Domaćin ovogodišnjega 18. kongresa je naša Muzička akademija koja je u svijetu poznata po izvrsnosti svoje Zagrebačke saksofonističke škole koju je utemeljio profesor Josip Nochta. Tijekom 5 dana, na više od 400 događanja, na brojnim mjestima u gradu će se predstaviti i susresti vrhunski glazbeni profesionalci, studenti i amateri. Bit će to, uvjeren sam, praznik glazbe, prigoda za promociju različitih stilova i izričaja te za razmjenu ideja. Svojom otvorenosti za publiku Kongres će obogatiti Zagrebačko kulturno ljeto te će doprinijeti boljem pozicioniranju Zagreba i Hrvatske na svjetskoj karti kulturnog turizma. Zahvaljujem organizatorima na uspješnoj realizaciji Kongresa, osobito red. prof. art. Draganu Sremcu, umjetničkomu ravnatelju Kongresa i prodekanu za umjetnost i poslovanje Muzičke akademije Sveučilišta u Zagrebu. Svim sudionicima želim uspješno sudjelovanje i ugodan boravak u našem gradu! Gradonačelnik Grada Zagreba Milan Bandić Major of the City of Zagreb Esteemed participants, dear guests, Zagreb is hosting the renowned World Saxophone Congress for the irst time. The host of this 18th Congress is our Academy of Music, world- famous for the excellence of its Zagreb School of Saxophone, established by professor Josip Nochta. In the course of 5 days, in more than 400 events at various locations in the city, top music professionals, students and amateurs will present themselves and meet each other. I am sure that it will be a celebration of music, an opportunity to promote various styles and expressions and to exchange ideas. -

Paul Green – Biography

Clarinet Jack Price Managing Director 1 (310) 254-7149 Skype: pricerubin [email protected] Rebecca Petersen Executive Administrator 1 (916) 539-0266 Skype: rebeccajoylove [email protected] Olivia Stanford Marketing Operations Manager [email protected] Karrah O’Daniel-Cambry Opera and Marketing Manager [email protected] Contents: Biography Mailing Address: Overview 1000 South Denver Avenue Career Highlights Suite 2104 Tulsa, OK 74119 Reviews Discography Website: Repertoire http://www.pricerubin.com Lectures and Workshops YouTube Links Personal Links Photo Gallery Complete artist information including video, audio and interviews are available at www.pricerubin.com Paul Green – Biography Paul Green at 13 in a televised Young People’s Concert with the New York Philharmonic and Leonard Bernstein, 1962. It has been a love affair that began when Paul Green was only eight years old. The orchestra teacher wanted Paul Green to play the viola, but once the young Paul heard the sound of the clarinet and picked it up in grammar school music class, it was clarinet or nothing. That determination fueled a passion for music and started an adventure that has led him around the world, thrilling audiences in his path, in an unusual career that few can match. Clearly a budding talent, Green began studying privately with the noted clarinet pedagogue Leon Russianoff. Accomplished at age 13, he was recommended to Leonard Bernstein by Stanley Drucker, first clarinetist of the New York Philharmonic. Green was chosen by Leonard Bernstein to be a featured guest in a televised Young People’s Concert with the New York Philharmonic in 1962, performing and recording Saint-Saens’ Carnival of the Animals as a thirteen year old. -

Flute: Late Style in Carl Nielsen’S Works for Flute

THE “ARCADIAN” FLUTE: LATE STYLE IN CARL NIELSEN’S WORKS FOR FLUTE A thesis submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS in the Performance Studies Division of the College-Conservatory of Music 2004 by Beth E. Chandler B.M., Baylor University, 1993 M.M., New England Conservatory, 1996 Committee Chair: bruce d. mcclung, Ph.D. ABSTRACT Revered as Denmark’s most celebrated musical figure and regarded as one of the finest, albeit under recognized composers, Carl Nielsen (1865–1931) holds a place as one of the most individual and creative artists of his time. Straddling the nineteenth and twentieth centuries and with consideration to the dramatically changing musical climate of that time, Nielsen’s vast output is stylistically complex. His music spans an array of styles, with elements of Romanticism in his early works, to an outright rejection of these same principles and an adoption of extensive progressivism in later works, all the while maintaining features of neoclassicism. There are six known works by Carl Nielsen that include flute in a solo or chamber role. These works date from his late, mature compositional period and include a short piece for solo flute from the incidental music to Aladdin, Op. 34 (1918–19); three pieces from the incidental music to Moderen (The mother), Op. 41 (1920): “Taagen letter” (The fog is lifting) for flute and piano or harp, “Børnene spiller” (The children are playing) for solo flute, and “Tro og håb spiller” (Faith and hope are playing) for flute and viola; the Wind Quintet, Op.