Elk Food Habits, Range Use and Movements, Gravelly Mountains

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Montana Forest Insect and Disease Conditions and Program Highlights

R1-16-17 03/20/2016 Forest Service Northern Region Montata Department of Natural Resources and Conservation Forestry Division In accordance with Federal civil rights law and U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) civil rights regulations and policies, the USDA, its Agencies, offices, and employees, and institutions participating in or administering USDA programs are prohibited from discriminating based on race, color, national origin, religion, sex, gender identity (including gender expression), sexual orientation, disability, age, marital status, family/parental status, income derived from a public assistance program, political beliefs, or reprisal or retaliation for prior civil rights activity, in any program or activity conducted or funded by USDA (not all bases apply to all programs). Remedies and complaint filing deadlines vary by program or incident. Persons with disabilities who require alternative means of communication for program information (e.g., Braille, large print, audiotape, American Sign Language, etc.) should contact the responsible Agency or USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TTY) or contact USDA through the Federal Relay Service at (800) 877-8339. Additionally, program information may be made available in languages other than English. To file a program discrimination complaint, complete the USDA Program Discrimination Complaint Form, AD-3027, found online at http://www.ascr.usda.gov/complaint_filing_cust.html and at any USDA office or write a letter addressed to USDA and provide in the letter all of the information requested in the form. To request a copy of the complaint form, call (866) 632-9992. Submit your completed form or letter to USDA by: (1) mail: U.S. -

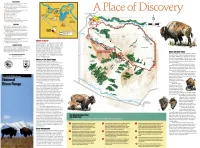

National Bison Range Is Administered by the U.S

REGULATIONS • Remain at your car and on the road. If you are near bison do not get out of your vehicle. • Hiking is permitted only on designated footpaths. • Trailers and other towed units are not allowed on the Red Sleep Mountain Drive. • Motorcycles and bicycles are permitted only on the paved drives below the cattle guards. x% Place of Discovery • No overnight camping allowed. • Firearms are prohibited. • All pets must be on a leash. • Carry out all trash. • All regulations are strictly enforced. • Our patrol staff is friendly and willing to answer your questions about the range and its wildlife. 3/4 MILE CAUTIONS • Bison can be very dangerous. Keep your distance. • All wildlife will defend their young and can hurt you. • Rattlesnakes are not aggressive but will strike if threatened. Watch where you step and do not go out into the grasslands. <* The Red Sleep Mountain Drive is a one-way mountain road. It gains 2000 feet in elevation and averages a 10% downgrade for about 2 miles. Be sure of your braking power. • Watch out for children on roadways especially in the picnic area and at popular viewpoints. • Refuge staff are trained in first aid and can assist you. Where to Start? Contact them in an emergency. The best place to start your visit to the ADMINISTRATION Bison Range is the Visitor Center. Here The National Bison Range is administered by the U.S. Fish you will find informative displays on and Wildlife Service as a part of the National Wildlife Refuge System. Further information can be obtained from the the bison, its history and its habitat. -

Native American Collections in the Archives

Examples of collections and resources supporting research about Land, Land Use, the Environment and Conservation in Montana held at Archives & Special Collections at the Mansfield Library, University of Montana-Missoula A separate list is available for collections with content focused on Forests and the Timber Products Industry. Note: In most cases links are provided from the titles of collections to the guides to those collections. The collections themselves are not digitized and therefore are not yet available online. This list is not comprehensive. Papers of Individuals and Families G. M. Brandborg Papers (1893-1977), Mss 691, 14.5 linear feet Papers of Guy M. "Brandy" Brandborg, long-time employee of the U. S. Forest Service, and Forest Supervisor of the Bitterroot National Forest from 1935-1955. The collection includes files related to Brandborg's interest in and activities related to wilderness, conservation, and watershed protection efforts in Montana, and two memorial scrapbooks documenting his activities in favor of sustainable timber harvesting and against extensive clearcutting. Stewart M. Brandborg Papers (1932-2000), Mss 699, 45.0 linear feet This collection consists of the professional papers of environmental activist Stewart M. Brandborg. A graduate of the University of Montana and the University of Idaho, Brandborg was hired as assistant conservation director for the National Wildlife Federation in 1954. In 1956 he was elected to the governing board of The Wilderness Society and in 1960 was hired as their associate executive director. He served as director of The Wilderness Society from 1964-1977. Brandborg’s papers include correspondence, research files and other documents from his time with The Wilderness Society, as well as material documenting his work with the National Wildlife Federation, the National Park Service, Wilderness Watch, and Friends of the Bitterroot (Montana.) Arnold Bolle Papers (1930-1994), Mss 600, 40.7 linear feet Arnold Bolle was a leading figure in the Montana conservation movement. -

COPYRIGHTED MATERIAL COPYRIGHTED I

Avalanche Campground (MT), 66 Big Horn Equestrian Center (WY), Index Avenue of the Sculptures (Billings, 368 MT), 236 Bighorn Mountain Loop (WY), 345 Bighorn Mountains Trail System INDEX A (WY), 368–369 AARP, 421 B Bighorn National Forest (WY), 367 Absaroka-Beartooth Wilderness Backcountry camping, Glacier Big Red (Clearmont, WY), 370 (MT), 225–227 National Park (MT), 68 Big Red Gallery (Clearmont, WY), Academic trips, 44–45 Backcountry permits 370 Accommodations, 413–414 Glacier National Park (MT), Big Salmon Lake (MT), 113 best, 8–10 54–56 Big Sheep Creek Canyon (MT), 160 for families with children, 416 Grand Teton (WY), 325 Big Sky (MT), 8, 215–220 Active vacations, 43–52 Yellowstone National Park Big Sky Brewing Company AdventureBus, 45, 269 (MT—WY), 264 (Missoula, MT), 93 Adventure Sports (WY), 309, 334 Backcountry Reservations, 56 Big Sky Candy (Hamilton, MT), 96 Adventure trips, 45–46 Backcountry skiing, 48 Big Sky Golf Course (MT), 217 AdventureWomen, 201–202 Backroads, 45, 46 Big Sky Resort (MT), 216–217 Aerial Fire Depot and Baggs (WY), 390 Big Sky Waterpark (MT), 131 Smokejumper Center (Missoula, Ballooning, Teton Valley (WY), Big Spring (MT), 188 MT), 86–87 306 Big Spring Creek (MT), 187 Air tours Bannack (MT), 167, 171–172 Big Timber Canyon Trail (MT), 222 Glacier National Park (MT), 59 Bannack Days (MT), 172 Biking and mountain biking, 48 the Tetons (WY), 306 Barry’s Landing (WY), 243 Montana Air travel, 409, 410 Bay Books & Prints (Bigfork, MT), Big Sky, 216 Albright Visitor Center 105 Bozeman, 202 (Yellowstone), 263, 275 -

Bison and Biodiversity: History of a Keystone Species

Spring/Summer 2020 MONTANA NTO PROMOTE ANDa CULTIVATE THEt APPRECIATION,u UNDERSTANDINGr AND STEWARDSHIPa OFli NATURE THROUGHs EDUCATIONt Bison and Biodiversity: History of a Keystone Species Heartbeats & Hibernation | All About Antlions | Birding in Spain and Montana | Visions of Earth MONTANA Naturalist Spring/Summer 2020 inside Features 4 BISON AND BIODIVERSITY: A CASE STUDY Exploring the history of North America’s keystone herbivore BY GIL GALE 8 HEARTBEATS AND HIBERNATION 4 8 IN THE ROCKIES Getting at the heart of surviving winter in Montana Departments BY HEATHER MCKEE 3 TIDINGS 10 NATURALIST NOTES Antlions: A Conversation of Observations 22 12 GET OUTSIDE GUIDE Book review: The Lost Words; 10 nature writing activity; phenology scavenger hunt; Kids’ Corner: tree painting by Lila Farrell; Pablo 4th-grade science projects 17 IMPRINTS Farewell to Lisa Bickell; upcoming exhibits; new summer 24 camp offerings; welcome to 24 Jennifer Robinson; Drop in with a FAR AFIELD Naturalist; As To The Mission; Birding in Spain 2019 auction thank yous BY PEGGY CORDELL 17 19 26 VOLUNTEER SPOTLIGHT MAGPIE MARKET Cover – A Bullock’s Oriole (Icterus bullockii) Alyssa Giffin perches on a branch above Pauline Creek at the National Bison Range on a gorgeous June 27 22 REFLECTIONS day. Bullock’s Orioles are summer residents COMMUNITY FOCUS Visions of Earth in Montana. Photo by Merle Ann Loman, Working for Wilderness: amontanaview.com. The Great Burn Conservation No material appearing in Montana Naturalist Alliance may be reproduced in part or in whole without the BY ALLISON DE JONG written consent of the publisher. All contents © 2020 The Montana Natural History Center. -

(USDA) Forest Service Working with Partners for Bird Conservation

U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) Forest Service Appendix A Working with Partners for Bird Conservation Bird Conservation Accomplishments Published 2004 This appendix lists the bird conservation accomplishment projects by USDA Forest Service Deputy Areas: National Forest Systems, Research and Development, State and Private and International Programs. This is not a complete set of the many bird conservation actions that have been or are currently being implemented across Forest Service Deputy Areas. It represents bird conservation accomplishment projects from the administrative units that replied at the time of the request. Projects started before fiscal year 2000 that are ongoing or conducted annually (beyond 2002) are reported as “ongoing” or “annually”, with the date of inception included (when known). I. National Forest Systems Region 1 (R-1): Northern Region Regionwide Accomplishments Partnership Enhancement • Partners in Flight (PIF) and Bird Conservation Region (BCR) Plans. Forest Service biologists throughout the Northern Region participated in the development of PIF and BCR plans for Montana, Idaho, North Dakota, and South Dakota. Active participation is ongoing with PIF working groups, BCR coordinators, joint venture meetings, and other activities that promote bird conservation. Partners in these efforts include the American Bird Conservancy (ABC), Montana Fish, Wildlife, & Parks (MFWP), Idaho Department of Fish and Game 1 (Idaho Fish & Game), U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service (USFWS), Bureau of Land Management (BLM), Potlatch Corp., Plum Creek Timber Co., local Audubon Society Chapters, and the Universities of Montana and Idaho. Ongoing since FY1993. • Montana Sage Grouse and Sagebrush Conservation Strategy. The Northern Region participated in the Montana Fish, Wildlife & Parks-led effort to develop a statewide sage grouse and sagebrush conservation strategy. -

National Park Service U.S

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Stewardship and Science DOI Bison Report Looking Forward Natural Resource Report NPS/NRSS/BRMD/NRR—2014/821 ON THE COVER Bison bull at southeastern Utah's Henry Mountains Photograph by Utah Division of Wildlife Resources DOI Bison Report Looking Forward Natural Resource Report NPS/NRSS/BRMD/NRR—2014/821 Prepared by the Department of the Interior Bison Leadership Team and Working Group National Park Service Biological Resource Management Division 1201 Oakridge Drive, Suite 200 Fort Collins, Colorado 80525 June 2014 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Fort Collins, Colorado The National Park Service, Natural Resource Stewardship and Science office in Fort Collins, Colorado, publishes a range of reports that address natural resource topics. These reports are of interest and applicability to a broad audience in the National Park Service and others in natural resource management, including scientists, conservation and environmental constituencies, and the public. The Natural Resource Report Series is used to disseminate high-priority, current natural resource management information with managerial application. The series targets a general, diverse audience, and may contain NPS policy considerations or address sensitive issues of management applicability. All manuscripts in the series receive the appropriate level of peer review to ensure that the information is scientifically credible, technically accurate, appropriately written for the intended audience, and designed and published in a professional manner. This report received informal peer review by subject-matter experts who were not directly involved in the collection, analysis, or reporting of the data. -

National Bison Range

National Bison Range Important Bird Areas are sites that provide essential habitat for threatened, unique, or particularly abundant species, during breeding, migration, or winter seasons. Browning Libby Whitefish Havre Malta Kalispell Glasgow Sidney Polson Great Falls National Bison Range Glendive Missoula Lewistown Deer Lodge Hamilton Anaconda Forsyth Butte Bozeman Billings Livingston Broadus Ennis Dillon Bald Eagle and The National Bison Range National Wildlife Refuge Grasshopper (NWR) and Important Bird Area (7,595 hectares) encompasses Sparrow rely on one of the country’s oldest National Wildlife refuges. It was habitats within this established in 1908 and lies within the Flathead Indian IBA. Reservation. The majority of the habitat is known as Palouse pairie, characterized by perennial bunch-grasses such as Idaho fescue and bluebunch wheatgrass, abundant wildflowers, deep soils, and rolling hills. It is one of the United State’s most endangered ecosystems. Another quarter of the IBA is composed of a varity of conifer, riparian, and shrubby draw habitats. The area supports many mammal species such as elk, deer, bighorn sheep, pronghorn antelope, black bears, mountain lion, and 350-500 bison, in addition to 200 species of birds. Cottonwood stands support the majority of these birds during nesting season and exist along portions of Mission, Pauline, Elk, and Trisky Bird Photos by Bob Martinka Photos by Bird creeks. Many are species of concern like Bald Eagle, Lewis’ Woodpecker, Red-naped Sapsucker, Willow Flycatcher, Lazuli www.mtaudubon.org Bunting, and Grasshopper Sparrow. National Bison Range Important Bird Area Landscape by Janene Lichtenberg Coordinated by BirdLife International, the Important Bird Areas (IBA) Program is a global initiative aimed at identifying and conserving the most important places for birds. -

Population Demography of the Yellowstone National Park Bison

POPULATION DEMOGRAPHY OF THE YELLOWSTONE NATIONAL PARK BISON HERDS by Julie Ann Fuller A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Fish and Wildlife Management MONTANA STATE UNIVERSITY Bozeman, Montana April 2006 © COPYRIGHT by Julie Ann Fuller 2006 All Rights Reserved ii Approval of a thesis submitted by Julie Ann Fuller This thesis has been read by each member of the thesis committee, and has been found to be satisfactory regarding content, English usage, format, citations, bibliographic style, and consistency, and is ready for submission to the Division of Graduate Education. Dr. Robert A. Garrott Approved for the Department of Ecology Dr. David W. Roberts Approved for the Division of Graduate Education Dr. Joseph J. Fedock iii STATEMENT OF PERMISSION TO USE In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a master’s degree at Montana State University, I agree that the Library shall make it available to borrowers under rules of the Library. If I have indicated my intention to copyright this thesis by including a copyright notice page, copying is allowable only for scholarly purposes, consistent with “fair use” as prescribed in the U.S. Copyright Law. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this thesis in whole or in parts may be granted only by the copyright holder. Julie Ann Fuller April 2006 iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This project would not have been possible without the vision of Dr. Robert Garrott and Dr. P. J. White. I am exceedingly grateful to Drs. Garrott and White for their support when my wolf-elk research took an unfortunate turn, and thank them for their patient guidance and constructive criticism throughout this research effort. -

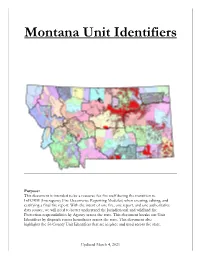

MT Unit Identifiers

Montana Unit Identifiers Purpose: This document is intended to be a resource for fire staff during the transition to InFORM (Interagency Fire Occurrence Reporting Modules) when creating, editing, and certifying a final fire report. With the intent of one fire, one report, and one authoritative data source, we will need to better understand the Jurisdictional and wildland fire Protection responsibilities by Agency across the state. This document breaks out Unit Identifiers by dispatch center boundaries across the state. This document also highlights the 56 County Unit Identifiers that are in place and used across the state. Updated March 4, 2021 MTLGXX Unit Identifiers: For fires occurring on lands not directly protected by a Montana recognized fire protection agency (i.e. BLM, USFS, USF&W, NPS, DNRC or BIA) PROTECTION initially fall to the responsibility of the respective County via the Montana State/County Cooperative Fire Protection (County Coop) arrangement. A MTLGXX should be assigned in these instances. Each County in Montana has an established NWCG Protection Unit ID and Jurisdiction Unit ID. Agency Duty Officers should be consulted for the appropriate assignment of a PROTECTION Unit Identifier for boundary line fires or mutual response/mutual threat zones (or as identified in a Local Operating Plan). Note: For private ownership, when populating JURISDICTION use the unit identifier of the County (MTLGXX). For private ownership when populating PROTECTION use the unit identifier of the protecting agency. For State lands not protected -

Off the Beaten Path a 20-Day Inspirational Itinerary

Off the Beaten Path A 20-day inspirational itinerary N N N N N N N N N N N N N N N N N N N N N N ® MONTANA NORTH DAKOTA SOUTH DAKOTA IDAHO UTAH WYOMING ITINERARY OVERVIEW TOTAL TRIP*: 4,105 MILES/6,918 KM | 84.5 HOURS DRIVING ARRIVAL GATEWAY: Salt Lake City (SLC) DAY 1: Idaho (Minnetonka Caves | Soda Springs | Lava Hot Springs) DAY 2: Idaho (Shoshone Falls) DAY 3: Idaho (Hells Canyon) DAY 4: Idaho (Route of the Hiawatha | Wallace) DAY 5: Montana (Missoula) DAY 6: Montana (Bitterroot Valley | Bannack | Butte) DAY 7: Montana (Virginia City & Nevada City | Bozeman) DAY 8: Montana (Livingston | Billings) DAY 9: North Dakota (Enchanted Highway) DAY 10: North Dakota (Minot – Home to Nørsk Hostfest | Scandinavian Park) DAY 11: North Dakota (International Peace Garden) DAY 12: North Dakota (Jamestown | Frontier Village) DAY 13: South Dakota (Aberdeen Watertown || Brookings) DAY 14: South Dakota (DeSmet | Pierre) DAY 15: South Dakota (Sturgis) DAY 16: South Dakota (Lead | Hill City) DAY 17: Wyoming (Thermopolis) DAY 18: Wyoming (Kilpecker Sand Dunes | Boar’s Tusk) DAY 19: Wyoming (Flaming Gorge) DAY 20: Wyoming (Fossil Butte) DEPARTURE GATEWAY: Salt Lake City (SLC) *Drive times and distances are approximate and meant for inspiration only DAY 1: IDAHO MINNETONKA CAVES | SODA SPRINGS | LAVA HOT SPRINGS ACTIVITIES: Head north from Salt Lake City to take a guided tour of Minnetonka Cave inside St. Charles Canyon above Bear Lake. The limestone cave stretches for a half-mile of enchanting stalactites, stalagmites and banded travertine. One of only two caverns administered by the U.S. -

Yellowstone Bison Petition

Petition to List the Yellowstone Bison as Threatened or Endangered Under the Endangered Species Act Western Watersheds Project & Buffalo Field Campaign In the Office of Endangered Species U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service United States Department of Interior November 13, 2014 Petition to List the Yellowstone Bison as Threatened or Endangered Under the Endangered Species Act Western Watersheds Project & Buffalo Field Campaign Table of Contents Petitioners ....................................................................................................................................................... 3 Summary ........................................................................................................................................................ 4 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................... 5 Petition History ..................................................................................................................................... 6 Biology and Natural History........................................................................................................................... 8 Taxonomy ............................................................................................................................................. 8 Description ............................................................................................................................................ 9 Distribution