The Prehistory of the Lolo and Bitterroot National Forests : an Overview

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aalseth Aaron Aarup Aasen Aasheim Abair Abanatha Abandschon Abarca Abarr Abate Abba Abbas Abbate Abbe Abbett Abbey Abbott Abbs

BUSCAPRONTA www.buscapronta.com ARQUIVO 35 DE PESQUISAS GENEALÓGICAS 306 PÁGINAS – MÉDIA DE 98.500 SOBRENOMES/OCORRÊNCIA Para pesquisar, utilize a ferramenta EDITAR/LOCALIZAR do WORD. A cada vez que você clicar ENTER e aparecer o sobrenome pesquisado GRIFADO (FUNDO PRETO) corresponderá um endereço Internet correspondente que foi pesquisado por nossa equipe. Ao solicitar seus endereços de acesso Internet, informe o SOBRENOME PESQUISADO, o número do ARQUIVO BUSCAPRONTA DIV ou BUSCAPRONTA GEN correspondente e o número de vezes em que encontrou o SOBRENOME PESQUISADO. Número eventualmente existente à direita do sobrenome (e na mesma linha) indica número de pessoas com aquele sobrenome cujas informações genealógicas são apresentadas. O valor de cada endereço Internet solicitado está em nosso site www.buscapronta.com . Para dados especificamente de registros gerais pesquise nos arquivos BUSCAPRONTA DIV. ATENÇÃO: Quando pesquisar em nossos arquivos, ao digitar o sobrenome procurado, faça- o, sempre que julgar necessário, COM E SEM os acentos agudo, grave, circunflexo, crase, til e trema. Sobrenomes com (ç) cedilha, digite também somente com (c) ou com dois esses (ss). Sobrenomes com dois esses (ss), digite com somente um esse (s) e com (ç). (ZZ) digite, também (Z) e vice-versa. (LL) digite, também (L) e vice-versa. Van Wolfgang – pesquise Wolfgang (faça o mesmo com outros complementos: Van der, De la etc) Sobrenomes compostos ( Mendes Caldeira) pesquise separadamente: MENDES e depois CALDEIRA. Tendo dificuldade com caracter Ø HAMMERSHØY – pesquise HAMMERSH HØJBJERG – pesquise JBJERG BUSCAPRONTA não reproduz dados genealógicos das pessoas, sendo necessário acessar os documentos Internet correspondentes para obter tais dados e informações. DESEJAMOS PLENO SUCESSO EM SUA PESQUISA. -

Photo Guide for Appraising Downed Woody Fuels in Montana Forests

This file was created by scanning the printed publication. Errors identified by the software have been corrected; however, some errors may remain. USDA FOREST SERVICE GENERAL TECHNICAL REPORT INT-96 NOVEMBER 1981 PHOTO GUIDE FOR APPRAISING DOWNED WOODY FUELS IN MONTANA FORESTS: Grand Fir- Larch-Douglas-Fir, Western Hemlock, Western Hemlock-Western Redcedar, and Western Redcedar Cover Types William C. Fischer INTERMOUNTAIN FOREST AND RANGE EXPERIMENT STATION U.S. DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE FOREST SERVICE OGDEN, UTAH 84401 THE AUTHOR WILLIAM C. FISCHER is a research forester for the Fire Effects and Use Research and Development Program, at the Northern Forest Fire Laboratory. His current assignment is to develop techniques and procedures for applying existing research knowledge to the task of producing improved operational fire management plans, with special emphasis on fire use, fuel treatment, and fuel management plans. Mr. Fischer received his bachelor's degree in forestry from the University of Michigan in 1956. From 1956 to 1966, he did Ranger District and forest staff work in timber management and fire control on the Boise National Forest. RESEARCH SUMMARY Four series of color photographs show different levels of ,downed woody material resulting from natural processes in four forest cover types in Montana. Each photo is supplemented by inventory data describing the size, weight, volume, and condition of the debris pictured. A subjective evaluation of potential fire behavior under an average bad fire weather situation is given. I nstructions are provided for using the photos to describe fuels and to evaluate potential fire hazard. USDA FOREST SERVICE GENERAL TECHNICAL REPORT INT-96 NOVEM,BER 1981 PHOTO GUIDE FOR APPRAISING DOWNED WOODY FUELS IN MONTANA FORESTS: Grand Fir- Larch-Douglas-Fir, Western Hemlock, We~tern Hemlock-Western Redcedar, and Western Redcedar Cover Types Will iam C. -

IMBCR Report

Integrated Monitoring in Bird Conservation Regions (IMBCR): 2015 Field Season Report June 2016 Bird Conservancy of the Rockies 14500 Lark Bunting Lane Brighton, CO 80603 303-659-4348 www.birdconservancy.org Tech. Report # SC-IMBCR-06 Bird Conservancy of the Rockies Connecting people, birds and land Mission: Conserving birds and their habitats through science, education and land stewardship Vision: Native bird populations are sustained in healthy ecosystems Bird Conservancy of the Rockies conserves birds and their habitats through an integrated approach of science, education and land stewardship. Our work radiates from the Rockies to the Great Plains, Mexico and beyond. Our mission is advanced through sound science, achieved through empowering people, realized through stewardship and sustained through partnerships. Together, we are improving native bird populations, the land and the lives of people. Core Values: 1. Science provides the foundation for effective bird conservation. 2. Education is critical to the success of bird conservation. 3. Stewardship of birds and their habitats is a shared responsibility. Goals: 1. Guide conservation action where it is needed most by conducting scientifically rigorous monitoring and research on birds and their habitats within the context of their full annual cycle. 2. Inspire conservation action in people by developing relationships through community outreach and science-based, experiential education programs. 3. Contribute to bird population viability and help sustain working lands by partnering with landowners and managers to enhance wildlife habitat. 4. Promote conservation and inform land management decisions by disseminating scientific knowledge and developing tools and recommendations. Suggested Citation: White, C. M., M. F. McLaren, N. J. -

Montana Forest Insect and Disease Conditions and Program Highlights

R1-16-17 03/20/2016 Forest Service Northern Region Montata Department of Natural Resources and Conservation Forestry Division In accordance with Federal civil rights law and U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) civil rights regulations and policies, the USDA, its Agencies, offices, and employees, and institutions participating in or administering USDA programs are prohibited from discriminating based on race, color, national origin, religion, sex, gender identity (including gender expression), sexual orientation, disability, age, marital status, family/parental status, income derived from a public assistance program, political beliefs, or reprisal or retaliation for prior civil rights activity, in any program or activity conducted or funded by USDA (not all bases apply to all programs). Remedies and complaint filing deadlines vary by program or incident. Persons with disabilities who require alternative means of communication for program information (e.g., Braille, large print, audiotape, American Sign Language, etc.) should contact the responsible Agency or USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TTY) or contact USDA through the Federal Relay Service at (800) 877-8339. Additionally, program information may be made available in languages other than English. To file a program discrimination complaint, complete the USDA Program Discrimination Complaint Form, AD-3027, found online at http://www.ascr.usda.gov/complaint_filing_cust.html and at any USDA office or write a letter addressed to USDA and provide in the letter all of the information requested in the form. To request a copy of the complaint form, call (866) 632-9992. Submit your completed form or letter to USDA by: (1) mail: U.S. -

New Mexico's Rich Cultural Heritage

New Mexico’s Rich Cultural Heritage Listed State and National Register Properties September 2012 Pictured clockwise: Acoma Curio Shop, Cibola County (1934); ); Belen Harvey House, Valencia County (888); Gate, Fence, and Hollow Tree Shelter Designed by Dionicio Rodriguez for B.C. Froman, Union County (1927); and Lyceum Theater, Curry County (1897). New Mexico’s Rich Cultural Heritage Listed State and National Register Properties Contents II Glossary 1-88 Section 1: Arranged by Name 1-144 Section2: Arranged by County 1-73 Section 3: Arranged by Number II Glossary Section 1: Arranged by Name Section 2: Arranged by County Section 3: Arranged by Number Section 3: Arranged by Number File# Name Of Property County City SR Date NR Date 1 Abo Mission Ruin NHL Torrance Scholle 10/15/1966 2 Anderson Basin NHL Roosevelt Portales 10/15/1966 3 Aztec Mill Colfax Cimarron 4 Barrio de Analco National Register Santa Fe Santa Fe 11/24/1968 Historic District NHL 5 Big Bead Mesa NHL Sandoval Casa Salazar 10/15/1966 6 Blumenschein, Ernest L., House NHL Taos Taos 10/15/1966 7 Carlsbad Reclamation Project NHL Eddy Carlsbad 10/15/1966 8 Carson, Kit, House NHL Taos Taos 10/15/1966 9 Folsom Man Site NHL Colfax Folsom 10/15/1966 10 Hawikuh Ruin NHL McKinley Zuni Pueblo 10/15/1966 11 Las Trampars Historic District NHL Taos Las Trampas 5/28/1967 12 Lincoln Historic District NHL Lincoln Lincoln 10/15/1966 13 Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory NHL Los Alamos Los Alamos 10/15/1966 14 Mesilla Plaza NHL Dona Ana Mesilla 10/15/1966 15 Old Fort Ruin Rio Arriba Blanco 1/21/1987 -

Honoring Yesterday, Inspiring Tomorrow

TALK ThistleThistle TALK Art from the heart Middle Schoolers expressed themselves in creating “Postcards to the Congo,” a unique component of the City as Our Campus initiative. (See story on page 13.) Winchester Nonprofi t Org. Honoring yesterday, Thurston U.S. Postage School PAID inspiring tomorrow. Pittsburgh, PA 555 Morewood Avenue Permit No. 145 Pittsburgh, PA 15213 The evolution of WT www.winchesterthurston.org in academics, arts, and athletics in this issue: Commencement 2007 A Fond Farewell City as Our Campus Expanding minds in expanding ways Ann Peterson Refl ections on a beloved art teacher Winchester Thurston School Autumn 2007 TALK A magnifi cent showing Thistle WT's own art gallery played host in November to LUMINOUS, MAGAZINE a glittering display of 14 local and nationally recognized glass Volume 35 • Number 1 Autumn 2007 artists, including faculty members Carl Jones, Mary Martin ’88, and Tina Plaks, along with eighth-grader Red Otto. Thistletalk is published two times per year by Winchester Thurston School for alumnae/i, parents, students, and friends of the school. Letters and suggestions are welcome. Please contact the Director of Communications, Winchester Thurston School, 555 Morewood Malone Scholars Avenue, Pittsburgh, PA 15213. Editor Anne Flanagan Director of Communications fl [email protected] Assistant Editor Alison Wolfson Director of Alumnae/i Relations [email protected] Contributors David Ascheknas Alison D’Addieco John Holmes Carl Jones Mary Martin ’88 Karen Meyers ’72 Emily Sturman Allison Thompson Printing Herrmann Printing School Mission Winchester Thurston School actively engages each student in a challenging and inspiring learning process that develops the mind, motivates the passion to achieve, and cultivates the character to serve. -

Research Natural Areas on National Forest System Lands in Idaho, Montana, Nevada, Utah, and Western Wyoming: a Guidebook for Scientists, Managers, and Educators

USDA United States Department of Agriculture Research Natural Areas on Forest Service National Forest System Lands Rocky Mountain Research Station in Idaho, Montana, Nevada, General Technical Report RMRS-CTR-69 Utah, and Western Wyoming: February 2001 A Guidebook for Scientists, Managers, and E'ducators Angela G. Evenden Melinda Moeur J. Stephen Shelly Shannon F. Kimball Charles A. Wellner Abstract Evenden, Angela G.; Moeur, Melinda; Shelly, J. Stephen; Kimball, Shannon F.; Wellner, Charles A. 2001. Research Natural Areas on National Forest System Lands in Idaho, Montana, Nevada, Utah, and Western Wyoming: A Guidebook for Scientists, Managers, and Educators. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-69. Ogden, UT: U.S. Departmentof Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. 84 p. This guidebook is intended to familiarize land resource managers, scientists, educators, and others with Research Natural Areas (RNAs) managed by the USDA Forest Service in the Northern Rocky Mountains and lntermountain West. This guidebook facilitates broader recognitionand use of these valuable natural areas by describing the RNA network, past and current research and monitoring, management, and how to use RNAs. About The Authors Angela G. Evenden is biological inventory and monitoring project leader with the National Park Service -NorthernColorado Plateau Network in Moab, UT. She was formerly the Natural Areas Program Manager for the Rocky Mountain Research Station, Northern Region and lntermountain Region of the USDA Forest Service. Melinda Moeur is Research Forester with the USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain ResearchStation in Moscow, ID, and one of four Research Natural Areas Coordinators from the Rocky Mountain Research Station. J. Stephen Shelly is Regional Botanist and Research Natural Areas Coordinator with the USDA Forest Service, Northern Region Headquarters Office in Missoula, MT. -

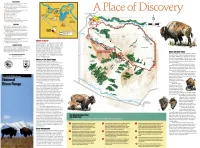

National Bison Range Is Administered by the U.S

REGULATIONS • Remain at your car and on the road. If you are near bison do not get out of your vehicle. • Hiking is permitted only on designated footpaths. • Trailers and other towed units are not allowed on the Red Sleep Mountain Drive. • Motorcycles and bicycles are permitted only on the paved drives below the cattle guards. x% Place of Discovery • No overnight camping allowed. • Firearms are prohibited. • All pets must be on a leash. • Carry out all trash. • All regulations are strictly enforced. • Our patrol staff is friendly and willing to answer your questions about the range and its wildlife. 3/4 MILE CAUTIONS • Bison can be very dangerous. Keep your distance. • All wildlife will defend their young and can hurt you. • Rattlesnakes are not aggressive but will strike if threatened. Watch where you step and do not go out into the grasslands. <* The Red Sleep Mountain Drive is a one-way mountain road. It gains 2000 feet in elevation and averages a 10% downgrade for about 2 miles. Be sure of your braking power. • Watch out for children on roadways especially in the picnic area and at popular viewpoints. • Refuge staff are trained in first aid and can assist you. Where to Start? Contact them in an emergency. The best place to start your visit to the ADMINISTRATION Bison Range is the Visitor Center. Here The National Bison Range is administered by the U.S. Fish you will find informative displays on and Wildlife Service as a part of the National Wildlife Refuge System. Further information can be obtained from the the bison, its history and its habitat. -

GEOLOGIC MAP of the LAME DEER 30. X 60. QUADRANGLE

PRELIMINARY GEOLOGIC MAP OF THE NEZ PERCE PASS 30' x 60' QUADRANGLE, WESTERN MONTANA Compiled and mapped by Richard B. Berg and Jeffrey D. Lonn Montana Bureau of Mines and Geology Open File Report MBMG 339 1996 This report has been reviewed for conformity with Montana Bureau of Mines and Geology’s technical and editorial standards. Partial support has been provided by the STATEMAP component of the National Cooperative Geology Mapping Program of the U.S. Geological Survey under contract Number 1434-94-A-91368. PRELIMINARY GEOLOGIC MAP OF THE NEZ PERCE PASS 30' X 60' QUADRANGLE, MONTANA Compiled and Mapped by Richard B. Berg and Jeffrey D Lonn DESCRIPTION OF MAP UNITS Qls LANDSLIDE DEPOSITS (HOLOCENE) Unsorted and unstratified mixtures of locally derived material transported down adjacent steep slopes and characterized by irregular hummocky surfaces. Occurs most often as earthflow movement on slopes underlain by Tertiary sedimentary (Tgc) and volcanic (Tv) rocks with high clay content. Qal ALLUVIAL DEPOSITS OF THE PRESENT FLOOD PLAIN (HOLOCENE) Fresh, well-sorted, well-rounded gravel and sand with a minor amount of silt and clay. Beneath modern flood plains and streams. Well logs show an average thickness of 40 feet (McMurtrey and others, 1972). Qat RIVER TERRACE DEPOSIT (LATE PLEISTOCENE?) Not exposed in outcrop, but the surfaces consist of unweathered, well-rounded, mostly granitic cobbles. These surfaces stand 15-25 feet above the present flood plain. Well logs indicate a thickness of 60-70 feet of sand, gravel, and cobbles. At least two terraces have been recognized (Uthman, 1988), but they are cannot be distinguished everywhere. -

Two High Altitude Game Trap Sites in Montana

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1974 Two High Altitude Game Trap Sites in Montana Bonnie Jean Hogan The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Hogan, Bonnie Jean, "Two High Altitude Game Trap Sites in Montana" (1974). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 9318. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/9318 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TWO HIGH ALTITUDE. GAME TRAP SITES IN MONTANA By Bonnie Herda Hogan B.A., University of Montana, 1969 Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts UNIVERSITY OF MONTANA 1974 Approved by: v s'sr~) s / '/ 7 / y ■Zu.£&~ fi-'T n Chairman, Board''of Examiners Gra< ie Schoo/1 ? £ Date UMI Number: EP72630 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Publishing UMI EP72630 Published by ProQuest LLC (2015). Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. -

Hydrogeologic Framework of the Upper Clark Fork River Area: Deer Lodge, Granite, Powell, and Silver Bow Counties R15W R14W R13W R12W By

Montana Bureau of Mines and Geology Montana Groundwater Assessment Atlas No. 5, Part B, Map 2 A Department of Montana Tech of The University of Montana July 2009 Open-File Version Hydrogeologic Framework of the Upper Clark Fork River Area: Deer Lodge, Granite, Powell, and Silver Bow Counties R15W R14W R13W R12W by S Qsf w Qsf Yb Larry N. Smith a n T21N Qsf Yb T21N R Authors Note: This map is part of the Montana Bureau of Mines and Geology (MBMG) a n Pz Pz Groundwater Assessment Atlas for the Upper Clark Fork River Area groundwater Philipsburg ValleyUpper Flint Creek g e Pz Qsf characterization. It is intended to stand alone and describe a single hydrogeologic aspect of the study area, although many of the areas hydrogeologic features are The town of Philipsburg is the largest population center in the valley between the Qsc interrelated. For an integrated view of the hydrogeology of the Upper Clark Fork Area Flint Creek Range and the John Long Mountains. The Philipsburg Valley contains 47o30 the reader is referred to Part A (descriptive overview) and Part B (maps) of the Montana 040 ft of Quaternary alluvial sediment deposited along streams cut into Tertiary 47o30 Groundwater Assessment Atlas 5. sedimentary rocks of unknown thickness. The east-side valley margin was glaciated . T20N Yb t R during the last glaciation, producing ice-sculpted topography and rolling hills in side oo B kf l Ovando c INTRODUCTION drainages on the west slopes of the Flint Creek Range. Prominent benches between ac la kf k B Blac oo N F T20N tributaries to Flint Creek are mostly underlain by Tertiary sedimentary rocks. -

United States Department of the Interior Geological

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Mineral resource potential of national forest RARE II and wilderness areas in Montana Compiled by Christopher E. Williams 1 and Robert C. Pearson2 Open-File Report 84-637 1984 This report is preliminary and has not been reviewed for conformity with U.S. Geological Survey editorial standards and stratigraphic nomenclature. 1 Present address 2 Denver, Colorado U.S. Environmental Protection Agency/NEIC Denver, Colorado CONTENTS (See also indices listings, p. 128-131) Page Introduction*........................................................... 1 Beaverhead National Forest............................................... 2 North Big Hole (1-001).............................................. 2 West Pioneer (1-006)................................................ 2 Eastern Pioneer Mountains (1-008)................................... 3 Middle Mountain-Tobacco Root (1-013)................................ 4 Potosi (1-014)...................................................... 5 Madison/Jack Creek Basin (1-549).................................... 5 West Big Hole (1-943)............................................... 6 Italian Peak (1-945)................................................ 7 Garfield Mountain (1-961)........................................... 7 Mt. Jefferson (1-962)............................................... 8 Bitterroot National Forest.............................................. 9 Stony Mountain (LI-BAD)............................................. 9 Allan Mountain (Ll-YAG)............................................