FINAL Bison Conservation and Management in Montana

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AMERICAN PRAIRIE RESERVE SEES RECORD VISITATION for 2020 Lodging Reservation System Now Open for 2021

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE FEBRUARY 1, 2021 Contact: Beth Saboe Senior Media and Government Relations Manager Phone: 406-600-4906 Email: [email protected] AMERICAN PRAIRIE RESERVE SEES RECORD VISITATION FOR 2020 Lodging reservation system now open for 2021 American Prairie Reserve experienced a surge of visitation in 2020, recording more people staying overnight at its facilities than any previous year. Overnight reservations last year were up nearly 200 percent compared to 2019. The uptick in visitation was driven in part by people seeking respite outdoors from the ongoing coronavirus pandemic, and came despite having only 40 percent of the Reserve’s camping and lodging inventory available due to COVID-19 precautions. According to American Prairie’s Director of Recreation and Public Access Mike Kautz, 665 reservations were recorded in 2020 from the Reserve’s three huts, and two campgrounds. In comparison, there were 232 reservations recorded in 2019. A reservation is defined as a group reserving one unit of lodging (campsite, hut or cabin), and not a count of individual visitors. Kautz says each reservation had an average group size of 4 people. In addition, the majority of people visiting the Reserve are Montanans. In 2020, more than 88% of the reservations for American Prairie’s hut system and more than 50% of reservations for the campgrounds came from state residents. Kautz says this growing interest suggests visitors should consider making reservations earlier this year. “Word of this pretty unique prairie experience we offer is quickly spreading,” said Kautz. “We fully expect our reservation inventory to fill up quickly this year so anyone who is curious about the lodging options shouldn’t wait too long.” Reservations for American Prairie’s 2021 visitation season are now being accepted, as of February 1. -

2020-2021 Arizona Hunting Regulations

Arizona Game and Fish Department 2020-2021 Arizona Hunting Regulations This publication includes the annual regulations for statewide hunting of deer, fall turkey, fall javelina, bighorn sheep, fall bison, fall bear, mountain lion, small game and other huntable wildlife. The hunt permit application deadline is Tuesday, June 9, 2020, at 11:59 p.m. Arizona time. Purchase Arizona hunting licenses and apply for the draw online at azgfd.gov. Report wildlife violations, call: 800-352-0700 Two other annual hunt draw booklets are published for the spring big game hunts and elk and pronghorn hunts. i Unforgettable Adventures. Feel-Good Savings. Heed the call of adventure with great insurance coverage. 15 minutes could save you 15% or more on motorcycle insurance. geico.com | 1-800-442-9253 | Local Office Some discounts, coverages, payment plans and features are not available in all states, in all GEICO companies, or in all situations. Motorcycle and ATV coverages are underwritten by GEICO Indemnity Company. GEICO is a registered service mark of Government Employees Insurance Company, Washington, DC 20076; a Berkshire Hathaway Inc. subsidiary. © 2019 GEICO ii ARIZONA GAME AND FISH DEPARTMENT — AZGFD.GOV AdPages2019.indd 4 4/20/2020 11:49:25 AM AdPages2019.indd 5 2020-2021 ARIZONA HUNTING4/20/2020 REGULATIONS 11:50:24 AM 1 Arizona Game and Fish Department Key Contacts MAIN NUMBER: 602-942-3000 Choose 1 for known extension or name Choose 2 for draw, bonus points, and hunting and fishing license information Choose 3 for watercraft Choose 4 for regional -

Montana Forest Insect and Disease Conditions and Program Highlights

R1-16-17 03/20/2016 Forest Service Northern Region Montata Department of Natural Resources and Conservation Forestry Division In accordance with Federal civil rights law and U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) civil rights regulations and policies, the USDA, its Agencies, offices, and employees, and institutions participating in or administering USDA programs are prohibited from discriminating based on race, color, national origin, religion, sex, gender identity (including gender expression), sexual orientation, disability, age, marital status, family/parental status, income derived from a public assistance program, political beliefs, or reprisal or retaliation for prior civil rights activity, in any program or activity conducted or funded by USDA (not all bases apply to all programs). Remedies and complaint filing deadlines vary by program or incident. Persons with disabilities who require alternative means of communication for program information (e.g., Braille, large print, audiotape, American Sign Language, etc.) should contact the responsible Agency or USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TTY) or contact USDA through the Federal Relay Service at (800) 877-8339. Additionally, program information may be made available in languages other than English. To file a program discrimination complaint, complete the USDA Program Discrimination Complaint Form, AD-3027, found online at http://www.ascr.usda.gov/complaint_filing_cust.html and at any USDA office or write a letter addressed to USDA and provide in the letter all of the information requested in the form. To request a copy of the complaint form, call (866) 632-9992. Submit your completed form or letter to USDA by: (1) mail: U.S. -

Drawn by the Bison Late Prehistoric Native Migration Into the Central Plains

DRAWN BY THE BISON LATE PREHISTORIC NATIVE MIGRATION INTO THE CENTRAL PLAINS LAUREN W. RITTERBUSH Popular images of the Great Plains frequently for instance, are described as relying heavily portray horse-mounted Indians engaged in on bison meat for food and living a nomadic dramatic bison hunts. The importance of these lifestyle in tune with the movements of the hunts is emphasized by the oft-mentioned de bison. More sedentary farming societies, such pendence of the Plains Indians on bison. This as the Mandan, Hidatsa, Pawnee, Oto, and animal served as a source of not only food but Kansa, incorporated seasonal long-distance also materials for shelter, clothing, contain bison hunts into their annual subsistence, ers, and many other necessities of life. Pursuit which also included gardening. In each case, of the vast bison herds (combined with the multifamily groups formed bands or tribal en needs of the Indians' horses for pasturage) af tities of some size that cooperated with one fected human patterns of subsistence, mobil another during formal bison hunts and other ity, and settlement. The Lakota and Cheyenne, community activities.! Given the importance of bison to these people living on the Great Plains, it is often assumed that a similar pattern of utilization existed in prehistory. Indeed, archeological KEY WORDS: migration, bison, Central Plains, studies have shown that bison hunting was Oneota, Central Plains tradition key to the survival of Paleoindian peoples of the Plains as early as 11,000 years ago. 2 If we Lauren W. Ritterbush is Assistant Professor of Anthropology at Kansas State University. -

The Laccolith-Stock Controversy: New Results from the Southern Henry Mountains, Utah

The laccolith-stock controversy: New results from the southern Henry Mountains, Utah MARIE D. JACKSON* Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland 21218 DAVID D. POLLARD Departments of Applied Earth Sciences and Geology, Stanford University, Stanford, California 94305 ABSTRACT rule out the possibility of a stock at depth. At Mesa, Fig. 1). Gilbert inferred that the central Mount Hillers, paleomagnetic vectors indi- intrusions underlying the large domes are Domes of sedimentary strata at Mount cate that tongue-shaped sills and thin lacco- floored, mushroom-shaped laccoliths (Fig. 3). Holmes, Mount Ellsworth, and Mount Hillers liths overlying the central intrusion were More recently, C. B. Hunt (1953) inferred that in the southern Henry Mountains record suc- emplaced horizontally and were rotated dur- the central intrusions in the Henry Mountains cessive stages in the growth of shallow (3 to 4 ing doming through about 80° of dip. This are cylindrical stocks, surrounded by zones of km deep) magma chambers. Whether the in- sequence of events is not consistent with the shattered host rock. He postulated a process in trusions under these domes are laccoliths or emplacement of a stock and subsequent or which a narrow stock is injected vertically up- stocks has been the subject of controversy. contemporaneous lateral growth of sills and ward and then pushes aside and domes the sed- According to G. K. Gilbert, the central intru- minor laccoliths. Growth in diameter of a imentary strata as it grows in diameter. After the sions are direct analogues of much smaller, stock from about 300 m at Mount Holmes to stock is emplaced, tongue-shaped sills and lacco- floored intrusions, exposed on the flanks of nearly 3 km at Mount Hillers, as Hunt sug- liths are injected radially from the discordant the domes, that grew from sills by lifting and gested, should have been accompanied by sides of the stock (Fig. -

The Bear in the Footprint: Using Ethnography to Interpret Archaeological Evidence of Bear Hunting and Bear Veneration in the Northern Rockies

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 2014 THE BEAR IN THE FOOTPRINT: USING ETHNOGRAPHY TO INTERPRET ARCHAEOLOGICAL EVIDENCE OF BEAR HUNTING AND BEAR VENERATION IN THE NORTHERN ROCKIES Michael D. Ciani The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Ciani, Michael D., "THE BEAR IN THE FOOTPRINT: USING ETHNOGRAPHY TO INTERPRET ARCHAEOLOGICAL EVIDENCE OF BEAR HUNTING AND BEAR VENERATION IN THE NORTHERN ROCKIES" (2014). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 4218. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/4218 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE BEAR IN THE FOOTPRINT: USING ETHNOGRAPHY TO INTERPRET ARCHAEOLOGICAL EVIDENCE OF BEAR HUNTING AND BEAR VENERATION IN THE NORTHERN ROCKIES By Michael David Ciani B.A. Anthropology, University of Montana, Missoula, MT, 2012 A.S. Historic Preservation, College of the Redwoods, Eureka, CA, 2006 Thesis presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Anthropology, Cultural Heritage The University of Montana Missoula, MT May 2014 Approved by: Sandy Ross, Dean of The Graduate School Graduate School Dr. Douglas H. MacDonald, Chair Anthropology Dr. Anna M. Prentiss Anthropology Dr. Christopher Servheen Forestry and Conservation Ciani, Michael, M.A., May 2014 Major Anthropology The Bear in the Footprint: Using Ethnography to Interpret Archaeological Evidence of Bear Hunting and Bear Veneration in the Northern Rockies Chairperson: Dr. -

Horned Animals

Horned Animals In This Issue In this issue of Wild Wonders you will discover the differences between horns and antlers, learn about the different animals in Alaska who have horns, compare and contrast their adaptations, and discover how humans use horns to make useful and decorative items. Horns and antlers are available from local ADF&G offices or the ARLIS library for teachers to borrow. Learn more online at: alaska.gov/go/HVNC Contents Horns or Antlers! What’s the Difference? 2 Traditional Uses of Horns 3 Bison and Muskoxen 4-5 Dall’s Sheep and Mountain Goats 6-7 Test Your Knowledge 8 Alaska Department of Fish and Game, Division of Wildlife Conservation, 2018 Issue 8 1 Sometimes people use the terms horns and antlers in the wrong manner. They may say “moose horns” when they mean moose antlers! “What’s the difference?” they may ask. Let’s take a closer look and find out how antlers and horns are different from each other. After you read the information below, try to match the animals with the correct description. Horns Antlers • Made out of bone and covered with a • Made out of bone. keratin layer (the same material as our • Grow and fall off every year. fingernails and hair). • Are grown only by male members of the • Are permanent - they do not fall off every Cervid family (hoofed animals such as year like antlers do. deer), except for female caribou who also • Both male and female members in the grow antlers! Bovid family (cloven-hoofed animals such • Usually branched. -

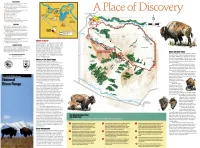

National Bison Range Is Administered by the U.S

REGULATIONS • Remain at your car and on the road. If you are near bison do not get out of your vehicle. • Hiking is permitted only on designated footpaths. • Trailers and other towed units are not allowed on the Red Sleep Mountain Drive. • Motorcycles and bicycles are permitted only on the paved drives below the cattle guards. x% Place of Discovery • No overnight camping allowed. • Firearms are prohibited. • All pets must be on a leash. • Carry out all trash. • All regulations are strictly enforced. • Our patrol staff is friendly and willing to answer your questions about the range and its wildlife. 3/4 MILE CAUTIONS • Bison can be very dangerous. Keep your distance. • All wildlife will defend their young and can hurt you. • Rattlesnakes are not aggressive but will strike if threatened. Watch where you step and do not go out into the grasslands. <* The Red Sleep Mountain Drive is a one-way mountain road. It gains 2000 feet in elevation and averages a 10% downgrade for about 2 miles. Be sure of your braking power. • Watch out for children on roadways especially in the picnic area and at popular viewpoints. • Refuge staff are trained in first aid and can assist you. Where to Start? Contact them in an emergency. The best place to start your visit to the ADMINISTRATION Bison Range is the Visitor Center. Here The National Bison Range is administered by the U.S. Fish you will find informative displays on and Wildlife Service as a part of the National Wildlife Refuge System. Further information can be obtained from the the bison, its history and its habitat. -

The Mackenzie Wood Bison (Bison Bison Athabascae) C.C

ARCTIC VOL. 43, NO. 3 (SEPTEMBER 1990) P. 231-238 Growth and Dispersal of an Erupting Large Herbivore Population in Northern Canada: The Mackenzie Wood Bison (Bison bison athabascae) C.C. GATES' and N.C. LARTER' (Received 6 September 1989; accepted in revised form Il January 1990) ABSTRACT. In 1963,18 wood bison (Bison bison athabuscue)were introduced to the Mackenzie Bison Sanctuary. Thepopulation has grown at a mean exponential rate of r = 0.215 f 0.007, reaching 1718 bison 2 10 months of age by April 1987. Analysis of annual population growth revealed a maximum exponential rateof r = 0.267 in 1975, followed by a declining rate, reaching a low value of r = 0.103 in 1987. Selective predation on calves was proposed as a mechanism to explain the declining rate of population growth. The area occupiedby the population increased at an exponential rate of0.228 f 0.017 km2.year". The dispersal ofmature males followed a pattern described as an innate process, while dispersal of females and juveniles exhibited characteristicsof pressure-threshold dispersal. Key words: erupting population, dispersal, wood bison, Bison bison athabascae, Northwest Rrritories RJ~SUMÉ.En 1963, on a introduit 18 bisons des bois(Bison bison athabuscue)dans la Rtserve de bisons Mackenzie.La population a connu un taux moyen de croissance exponentielle der= 0,215 f 0,007, atteignant 1718 bisons qui avaient 10 mois ou plus en avril 1987. Une analyse de la croissance annuelle de la population montre un taux moyen de croissance exponentielle der = 0,267 en 1975, suivid'un taux en baisse jusqu'B r = 0,103 en 1987.On avanceque la prkdation selectives'optrant sur les veauxexplique la baisse du taux de croissance lade population. -

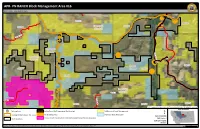

APR- PN RANCH Block Management Area #16 BMA Rules - See Reverse Page

APR- PN RANCH Block Management Area #16 BMA Rules - See Reverse Page Ch ip C re e k 23N15E 23N17E 23N16E !j 23N14E Deer & Elk HD # 690 Rd ille cev Gra k Flat Cree Missouri River k Chouteau e e r C County P g n o D B r i d g e Deer & Elk R d HD # 471 UV236 !j Fergus 22N17E 22N14E County 22N16E 22N15E A Deer & Elk r ro w The Peak C HD # 426 r e e k E v Judi e th r Riv s e ge Rd r Ran o n R d 21N17E 21N15E 21N16E U.S. Department of Agriculture Farm Services Agency Aerial Photography Field Office Area of Interest !j Parking Area Safety Zone (No Trespassing, No Hunting) US Bureau of Land Management º 1 6 Hunting Districts (Deer, Elk, Lion) No Shooting Area Montana State Trust Land 4 Date: 5/22/2020 2 Moline Ranch Conservation Easement (Seperate Permission Required) FWP Region 4 7 BMA Boundary 5 BLM 100K Map(s): 3 Winifred Possession of this map does not constitute legal access to private land enrolled in the BMA Program. This map may not depict current property ownership outside the BMA. It is every hunter's responsibility to know the 0 0.5 1 land ownership of the area he or she intends to hunt, the hunting regulations, and any land use restrictions that may apply. Check the FWP Hunt Planner for updates: http://fwp.mt.gov/gis/maps/huntPlanner/ Miles AMERICAN PRAIRIE RESERVE– PN RANCH BMA # 16 Deer/Elk Hunting District: 426/471 Antelope Hunting District: 480/471 Hunting Access Dates: September 1 - January 1 GENERAL INFORMATION HOW TO GET THERE BMA Type Acres County Ownership » North on US-191 15.0 mi 2 20,203 Fergus Private » North on Winifred Highway 24.0 mi » West on Main St. -

Wood Bison (Bison Bison Athabascae)

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Threatened and Endangered Species Wood Bison (Bison bison athabascae) The wood bison (Bison bison athabascae) is the largest native land mammal in North America. They have a large triangular head, a thin beard, and rudimentary throat mane; their horns usually extend above the hair on their head; and the highest point of their hump is forward of their front legs. These physical characteristics distinguish them from the plains bison (Bison bison bison), which is the subspecies that occurs on the prairies of the continental United States. Protected Status The wood bison is listed as threatened under the 1973 Endangered Species Act (ESA). In Canada the wood bison is protected as threatened under the Species at Risk Act. Range and Population Size The wood bison is adapted to meadow Wood bison cow and calf at the Alaska Wildlife Conservation Center. Doug Lindstrand and forest habitats in subarctic regions. Historically, its range was generally north of that occupied by Canada, hunting is strictly regulated uninfected herds. Captive herds the plains bison, and included most and is not a threat to the species as of disease-free animals have been boreal regions of northern Alberta; it once was. The main threats are established in both Alaska and northeastern British Columbia; diseases of domestic cattle (bovine Russia. a small portion of northwestern tuberculosis and bovine brucellosis), Saskatchewan; the western which were unintentionally introduced Alaska’s Captive Herd Northwest Territories; most of the to wood bison in the early 1920s, The captive herd in Alaska is being Yukon Territory; and much of interior and loss of habitat (primarily from cared for at the Alaska Wildlife Alaska. -

Riparian Restoration Summary

American Prairie Reserve & Prairie Stream Restoration Introduction to American Prairie Foundation American Prairie Foundation (APF) is spearheading a historic effort to reignite America’s passion for large-scale conservation by assembling the largest wildlife reserve of any kind in the lower 48 states. APF’s lands, called American Prairie Reserve (APR), are located on Montana’s Great Plains, just north of the Charles M. Russell National Wildlife Refuge and the Missouri River. Scientists have identified this place as an ideal location for the construction of a thriving prairie reserve capable of hosting an astonishing array of wildlife in an ecologically diverse environment. APF currently holds 123,346 acres of deeded and leased land. APF has three goals informing all activities on the Reserve: 1. Conservation: APF seeks to accumulate and manage enough private land that, when combined with existing public land, will create a fully functioning prairie-based wildlife reserve. When complete, the Reserve will consist of more than three million acres of private and public land (using the existing 1.1 million acre Charles M. Russell National Wildlife Refuge as the public land anchor). With less than 1% of the world’s grasslands protected, the pristine condition of the land and abundance of indigenous species in the Northern Great Plains make the American Prairie Reserve region an ideal location for a conservation project of this scale. APF currently manages a conservation bison herd of approximately 140 animals—the first conservation bison herd in this part of Montana in more than 120 years. Collaborative research projects are also underway to assess existing populations of endemic species including pronghorn, prairie dogs, swift fox, long- billed curlews, and cougars.