ARSC Journal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chronology 1916-1937 (Vienna Years)

Chronology 1916-1937 (Vienna Years) 8 Aug 1916 Der Freischütz; LL, Agathe; first regular (not guest) performance with Vienna Opera Wiedemann, Ottokar; Stehmann, Kuno; Kiurina, Aennchen; Moest, Caspar; Miller, Max; Gallos, Kilian; Reichmann (or Hugo Reichenberger??), cond., Vienna Opera 18 Aug 1916 Der Freischütz; LL, Agathe Wiedemann, Ottokar; Stehmann, Kuno; Kiurina, Aennchen; Moest, Caspar; Gallos, Kilian; Betetto, Hermit; Marian, Samiel; Reichwein, cond., Vienna Opera 25 Aug 1916 Die Meistersinger; LL, Eva Weidemann, Sachs; Moest, Pogner; Handtner, Beckmesser; Duhan, Kothner; Miller, Walther; Maikl, David; Kittel, Magdalena; Schalk, cond., Vienna Opera 28 Aug 1916 Der Evangelimann; LL, Martha Stehmann, Friedrich; Paalen, Magdalena; Hofbauer, Johannes; Erik Schmedes, Mathias; Reichenberger, cond., Vienna Opera 30 Aug 1916?? Tannhäuser: LL Elisabeth Schmedes, Tannhäuser; Hans Duhan, Wolfram; ??? cond. Vienna Opera 11 Sep 1916 Tales of Hoffmann; LL, Antonia/Giulietta Hessl, Olympia; Kittel, Niklaus; Hochheim, Hoffmann; Breuer, Cochenille et al; Fischer, Coppelius et al; Reichenberger, cond., Vienna Opera 16 Sep 1916 Carmen; LL, Micaëla Gutheil-Schoder, Carmen; Miller, Don José; Duhan, Escamillo; Tittel, cond., Vienna Opera 23 Sep 1916 Die Jüdin; LL, Recha Lindner, Sigismund; Maikl, Leopold; Elizza, Eudora; Zec, Cardinal Brogni; Miller, Eleazar; Reichenberger, cond., Vienna Opera 26 Sep 1916 Carmen; LL, Micaëla ???, Carmen; Piccaver, Don José; Fischer, Escamillo; Tittel, cond., Vienna Opera 4 Oct 1916 Strauss: Ariadne auf Naxos; Premiere -

Ariadne Auf Naxos

La natura és l'origen de totes les coses bones. Yoghourts, flams, cremes, formatges. —aliments frescos i naturals— GRAN TEATRE DEL LICEU Temporada d'òpera 1983/84 CONSORCI DEL GRAN TEATRE DEL LICEU CENERALHAT DE CATALUNYA AJUNTAMENT DE BARCELONA SOCIETAT DEL GRAN TEATRE DEL LICEU Ptas.1,949.480PRECIO: decirfaltahaceNomás dynamicThecar BRITISH Tels. Tels. S.A.MOTORS, 46-48Gervasio.SanP.»VENTAS:YEXPOSICION Q38211373124797- 36Calabna,RECAMBIOS:YTALLERES BARCELONA242922314-- ARIADIME AUF IMAXOS òpera en 1 pròleg i 1 acte Llibret d'Hugo von Hofmannsthal Miisica de Richard Strauss Funció de Gala Dijous, 12 de gener de 1984, a les 21 h., funció núm. 23, torn B Diumenge, 15 de gener de 1984, a les 17 h., funció núm. 24, torn T Dimecres, 18 de gener de 1984, a les 21 h., funció núm. 25, torn A GRAN TEATRE DEL LICEU Barcelona HïïVÜS ^ROSSO^ fWlW^ATI martini & ROSSI Un Martini invitaavivir [martini ARIADNE AUF NAXOS El majordom (part parlada): Hans Christian Un mestre de miisica: Ernst Gutstein El compositor: Alicia Nafé Bacchus: Klaus Koening Un oficial: Alfredo Heilbron Un mestre de ball: Wolf Appel Un perruquer: Steven Kimbrough Un lacai: Alfred Werner Zerbinetta: Celina Lindsley Ariadne: Montserrat Caballé Arlequí: Georg Tichy Scaramuccio: Ernst Dieter Suttheimer Truffaldin: Ude Krekow Brighella: Wolf Appel Echo: Downing Whitesell Najade: Agnes Habereder Dryade: Ingrid Mayr Director d'orquestra: János Kulka Director d'escena: Mario Kriiger Violí concertino: Josep M." Alpiste Producció: Staatstheater - Braunschweig (R.F.A.) ORQUESTRA SIMFÒNICA DEL GRAN TEATRE DEL LICEU Comentaris a càrrec dels Drs. Roger Alier, Xosé Aviñoa i Oriol Martorell, del Departament d'Art de la Universitat de Barcelona. -

Richard Strauss Seine Kindheit Und Jugend Verlebte Richard Strauss in München, Worauf Kapellmeisterengagements Ihn 1885 * 11

Strauss, Richard Richard Strauss Seine Kindheit und Jugend verlebte Richard Strauss in München, worauf Kapellmeisterengagements ihn 1885 * 11. Juni 1864 in München, Deutschland nach Meiningen, 1886 zurück nach München und 1889 † 8. September 1949 in Garmisch, Deutschland nach Weimar führten. Nach einer abermaligen Anstel- lung an der Münchner Hofoper von 1894 bis 1898 ging Komponist, Dirigent, Opernleiter, Kulturpolitiker er 1898 als Hofkapellmeister nach Berlin und übernahm 1918 zusammen mit Franz Schalk die Leitung der Wiener »Wahre Kunst adelt jeden Saal und anständiger Gelder- Hofoper bis 1924. Seit 1908 besaß er eine Villa in Garmi- werb für Frau und Kinder schändet nicht – einmal einen sch, ab 1925 eine in Wien. Nach dem Ende des Zweiten Künstler.« Weltkriegs lebte Strauss in der Schweiz, bis er kurz vor seinem Tod 1949 nach Garmisch zurückkehrte. Eine um- Richard Strauss 1908 in Entgegnung auf Vorwürfe, dass fangreiche Reisetätigkeit als Dirigent hatte ihn von jun- er 1904 zwei Konzerte in dem New Yorker Wanamaker- gen Jahren an bis ins hohe Alter in zahlreiche Orte des Kaufhaus dirigiert hatte, zitiert nach Walter Werbeck: In- und Auslandes geführt. Einleitung, in: Werbeck 2014, S. 9. Biografie Profil Richard Strauss wurde 1864 in München als Sohn des Richard Strauss war einer der erfolgreichsten und zug- Ersten Hornisten der Münchner Hofoper Franz Strauss leich umstrittensten Musiker seiner Zeit. Als Komponist und seiner Frau Josepha Pschorr, einer Tochter des Brau- arbeitete er hauptsächlich in den Gattungen Oper, Sinfo- ereibesitzers Georg Pschorr d. Ä. geboren. Mit vier Jah- nische Dichtung und Lied. Im Zentrum seiner musikali- ren erhielt er ersten Klavierunterricht bei dem Harfenis- schen Ästhetik stand das Ziel, in Tönen plastisch und ten August Tombo, mit acht Jahren Geigenunterricht bei konkret menschliche Konflikte auszudrücken und indivi- Benno Walter, der Konzertmeister der Münchner Hof- duelle Charaktere zu schildern. -

TOCC0500DIGIBKLT.Pdf

JULIUS BITTNER, FORGOTTEN ROMANTIC by Brendan G. Carroll Julius Bittner is one of music’s forgotten Romantics: his richly melodious works are never performed today and he is perhaps the last major composer of the early twentieth century to have been entirely ignored by the recording industry – until now: apart from four songs, this release marks the very first recording of any of his music in modern times. It reveals yet another colourful and individual voice among the many who came to prominence in the period before the First World War – and yet Bittner, an important and integral part of Viennese musical life before the Nazi Anschluss of 1938 subsumed Austria into the German Reich, was once one of the most frequently performed composers of contemporary opera in Austria. He wrote in a fluent, accessible and resolutely tonal style, with an undeniable melodic gift and a real flair for the stage. Bittner was born in Vienna on 9 April 1874, the same year as Franz Schmidt and Arnold Schoenberg. Both of his parents were musical, and he grew up in a cultured, middle-class home where artists and musicians were always welcomed (Brahms was a friend of the family). His father was a lawyer and later a distinguished judge, and initially young Julius followed his father into the legal profession, graduating with honours and eventually serving as a senior member of the judiciary throughout Lower Austria, until 1920. He subsequently became an important official in the Austrian Department of Justice, until ill health in the mid-1920s forced him to retire (he was diabetic). -

C K’NAY C (To Her) C (Poem by A

K ney C k’NAY C (To Her) C (poem by A. Belïy [(A.) BAY-lee] set to music by Sergei Rachmaninoff [sehr-GAYEE rahk-MAH-nyih-nuff]) Kaan C JindÍich z Albestç Kàan C YINND-rshihk z’AHL-bess-too KAHAHN C (known also as Heinrich Kàan-Albest [H¦N-rihh KAHAHN-AHL-besst]) Kabaivanska C Raina Kabaivanska C rah-EE-nah kah-bahih-WAHN-skuh C (known also as Raina Yakimova [yah-KEE-muh-vuh] Kabaivanska) Kabalevsky C Dmitri Kabalevsky C d’MEE-tree kah-bah-LYEFF-skee C (known also as Dmitri Borisovich Kabalevsky [d’MEE-tree bah-REE-suh-vihch kah-bah-LYEFF-skee]) C (the first name is also transliterated as Dmitry) Kabasta C Oswald Kabasta C AWSS-vahlt kah-BAHSS-tah Kabelac C Miloslav Kabelá C MIH-law-slahf KAH-beh-lahahsh Kabos C Ilona Kabós C IH-law-nuh KAH-bohohsh Kacinskas C Jerome Ka inskas C juh-ROHM kah-CHINN-skuss C (known also as Jeronimas Ka inskas [yeh-raw-NEE-mahss kah-CHEEN-skahss]) Kaddish for terezin C Kaddish for Terezin C kahd-DIHSH (for) TEH-reh-zinn C (a Holocaust Requiem [{REH-kôôee-umm} REH-kôôih-emm] by Ronald Senator [RAH-nulld SEH-nuh-tur]) C (Kaddish is a Jewish mourner’s prayer, and Terezin is a Czechoslovakian town converted to a concentration camp by the Nazis during World War II, where more than 15,000 Jewish children perished) Kade C Otto Kade C AWT-toh KAH-duh Kadesh urchatz C Kadesh Ur'chatz C kah-DEHSH o-HAHTSS C (Bless and Wash — a prayer song) Kadosa C Pál Kadosa C PAHAHL KAH-daw-shah Kadosh sanctus C Kadosh, Sanctus C kah-DAWSH, SAHNGK-tawss C (section of the Holocaust Reqiem — Kaddish for Terezin [kahd-DIHSH (for) TEH-reh-zinn] -

THE RECORD COLLECTOR MAGAZINE Given Below Is the Featured Artist(S) of Each Issue (D=Discography, B=Biographical Information)

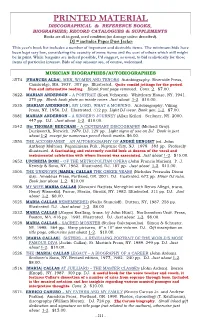

PRINTED MATERIAL DISCOGRAPHICAL & REFERENCE BOOKS, BIOGRAPHIES; RECORD CATALOGUES & SUPPLEMENTS Books are all in good, used condition (no damage unless described). DJ = includes Paper Dust Jacket This year’s book list includes a number of important and desirable items. The minimum bids have been kept very low, considering the scarcity of some items and the cost of others which still might be in print. While bargains are indeed possible, I’d suggest, as usual, to bid realistically for those items of particular interest. Bids of any amount are, of course, welcomed. MUSICIAN BIOGRAPHIES/AUTOBIOGRAPHIES 3574. [FRANCES ALDA]. MEN, WOMEN AND TENORS. Autobiography. Riverside Press, Cambridge, MA. 1937. 307 pp. Illustrated. Quite candid jottings for the period. Fun and informative reading. Blank front page removed. Cons. 2. $7.00. 3622. MARIAN ANDERSON – A PORTRAIT (Kosti Vehanen). Whittlesey House, NY. 1941. 270 pp. Blank book plate on inside cover. Just about 1-2. $10.00. 3535. [MARIAN ANDERSON]. MY LORD, WHAT A MORNING. Autobiography. Viking Press, NY. 1956. DJ. Illustrated. 312 pp. Light DJ wear. Book gen. 1-2. $7.00. 3581. MARIAN ANDERSON – A SINGER’S JOURNEY (Allan Keiler). Scribner, NY. 2000. 447 pp. DJ. Just about 1-2. $10.00. 3542. [Sir THOMAS] BEECHAM – A CENTENARY DISCOGRAPHY (Michael Gray). Duckworth, Norwich. 1979. DJ. 129 pp. Light signs of use on DJ. Book is just about 1-2 except for numerous pencil check marks. $6.00. 3550. THE ACCOMPANIST – AN AUTOBIOGRAPHY OF ANDRÉ BENOIST (ed. John Anthony Maltese). Paganiniana Pub., Neptune City, NJ. 1978. 383 pp. Profusely illustrated. A fascinating and extremely candid look at dozens of the vocal and instrumental celebrities with whom Benoist was associated. -

University of Southampton Research Repository Eprints Soton

University of Southampton Research Repository ePrints Soton Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given e.g. AUTHOR (year of submission) "Full thesis title", University of Southampton, name of the University School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination http://eprints.soton.ac.uk UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON FACULTY OF HUMANITIES Department of Music Volume 2 of 2 Heinrich Schenker and the Radio by Kirstie Hewlett Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 2014 1 1 Appendices 1 1 Contents Appendix 1: References to Radio Broadcasts.............................................................. 1 1924 ........................................................................................................................................................................ 3 1925 ......................................................................................................................................................................11 1926 ......................................................................................................................................................................53 -

78Rpm to Sell !

Beginning ! ! 78rpm to sell ! ! ! Albums : Lotte Lehmann : Schubert + Schumann + Brahms (3x) Columbia US Sir Charles Thomas Victor Grace Moore Lily Pons Mario Lanza Yves Thymaire Voices of the Golden age (volume 1 Victor) Gilbert & Sullivan Princess Ida HMV OA + HMS Pinafore Decca Vaughan Williams On wenlock wedge Pears Jeaette Mc Donald in songs Blanche Thebom Schumann Jennies Tourel Offenbach Dorothy Maynor Spirituals Hulda Lahanska Lieder recital Erna Sack Popular favorites Eileen Farrell Irish songs Paul Robeson Spirituals Josef Schmidt Lotte Lehmann Strauss Lotte Lehmann Song recital Maggie Teyte French art songs Gladys Swarthout pˆopular favorites Maggie Teyte Debussy with Cortot Lotte Lehmann Schumann with Bruno Walter Lotte Lehmann Brahms Index Ada ASLOP, 44 Alma GLUCK, 38, 51 Ada NORDENOVA, 96, 97 Amelita GALLI-CURCI, 27, 30, 32, 57, 63, 72 Adamo DIDUR, 99 Anne ROSELLE, 25 Adele KERN, 17, 18, 46, 74, 77 Anny SCHLEMM, 45 Alda NONI, 14, 17, 48, 60, 74 Anny von STOSCH, 91 Alessandro BONCI, 57 Antenore REALI, 40 Alessandro VALENTE, 58, 67 Antonio CORTIS, 58, 60 Alexander KIPNIS, 71, 72, 77 Antonio SCOTTI, 30 Alexander SVED, 47 Armand TOKATYAN, 65 Alexandra TRIANTI, 76 Arno SCHELLENBERG, 71 Alexandre KOUBITSKY, 49 Arthur ENDREZE, 61, 85, 86 Alexandre KRAIEFF, 23 Arthur PACYNA, 58 Alfons FUGEL, 40 Astra DESMOND, 41, 59 Alfred JERGER, 57 August SEIDER, 47 Alfred PICCAVER, 25, 26, 96 Augusta OLTRABELLA, 46, 87 Alina BOLECHOWSKA, 46 Aulikki RAUTAWAARA, 100 Barbara KEMP, 23 Cesare FORMICHI, 99 Bernardo de MURO, 32, 50 Cesare PALAGI, 78 Bernhard -

AUTOGRAPH AUCTION Sunday 27 November 2011 10:00

AUTOGRAPH AUCTION Sunday 27 November 2011 10:00 International Autograph Auctions (IAA) Office address Foxhall Business Centre Foxhall Road NG7 6LH International Autograph Auctions (IAA) (AUTOGRAPH AUCTION) Catalogue - Downloaded from UKAuctioneers.com Lot: 877 beneath the quotation. VG ELGAR EDWARD: (1857-1934) English Composer. A good Estimate: £80.00 - £100.00 printed score signed for The Dream of Gerontius (Op.38, 1900), First Edition published by Novello and Company Ltd., London, 1900. The tall 8vo edition has been specially bound in half blue Lot: 883 morocco with gilt title ('Nesta') to cover and gilt lettering to COATES ERIC: (1886-1957) English Composer, composed the spine. Signed by Elgar in dark fountain pen ink to the famous main title march of the film score to The Dam Busters preliminary blank with an A.M.Q.S. in his hand, two bars with (1954). Vintage signed and inscribed 4 x 6 photograph, a head words ('Praise etc.') beneath his signature. Dated Hereford, and shoulders study of Coates. Signed in dark fountain pen ink 1924, in his hand. Bearing two ownership signatures of N[esta]. to a light area of the image and dated February 1933 in his J. R. Clarke of Gloucester and Chester, one to the title page. hand. VG Rare in this form. Some light discoloration to the head of the Estimate: £100.00 - £120.00 covers and the spine faded, about VG Estimate: £400.00 - £600.00 Lot: 884 BRITTEN BENJAMIN: (1913-1976) English Composer. Vintage Lot: 878 signed postcard photograph of Britten in a head and shoulders SULLIVAN ARTHUR: (1842-1900) English Composer. -

Inhalt Bandi Einleitung I Vorspiel Auf Dem Theater — Eine Stimme Zur Rechten Zeit ...I Vollendung Und Ende Des Belcanto

Inhalt Bandi Vorwort XXVII Einleitung i Vorspiel auf dem Theater — Eine Stimme zur rechten Zeit .... i Vollendung und Ende des Belcanto: Enrico Caruso 3 Vom Erbe — über das Erben 9 I. Kapitel Dialog mit der Ewigkeit 19 In der Welt der Erinnerung zählt die Zeit nicht 19 Auf der Suche nach der verlorenen Zeit 26 Sänger und Schallplatte 28 Von Treue und Untreue 34 II. Kapitel Belcanto 39 Goldenes Zeitalter 39 Heiliger Geist — Hermaphrodit — Modern Heroe — Die übernatürlich schöne Stimme 46 Paradigma: Farinelli 48 Das Ende der Gesangskunst? 55 III. Kapitel Der ferne Klang oder: Die alte Schule 59 Nachtigall: Adelina Patti 59 • Auf Flügeln des Gesanges: Marcella Sembrich 67 Exkurs: Die Schule der Mathilde Marchesi 73 Assoluta: Lilli Lehmann 76 • Yankee-Diva: Lillian Nórdica 83 • Der léate Rokoko-Tenor: Fernando de Lucia 88 • La voix unique du monde: Fran- cesco Tamagno 99 • Exkurs: Die Zerstörung des Helden: Francesco Tamagno und die Otello-Tradition 104 • Magisches Wispern: Victor Maurel 112 • La Gloria d'Italia: Mattia Battistini 115 • Der vollkommene Sänger: Pol Plançon 122 IV. Kapitel Richard Wagner: Die menschliche Stimme ist die Grundlage aller Musik 12.7 Der Darsteller ist der wahre Künstler 127 Die Oper oder: Das Narrenhaus für allen Wahnsinn der Welt . 129 Inhalt VII Bibliografische Informationen digitalisiert durch http://d-nb.info/1008288748 Der dramatische Gesang 132 Paradigma I — Die Utopie von der vollkommenen Tenorstimme oder: Joseph Tichatschek 137 Paradigma II - Das Gesangsgenie ohne Stimme oder: Wilhelmine Schröder-Devrient 139 Wenn sich die Theorie der Wirklichkeit nicht fügt 144 Gesang als Handlung 147 Die Frage des Belcanto 149 Gesang und Sprache: Wagner, der Lautkomponist 159 Entwicklungen des Wagner-Gesangs 163 V. -

PRINTED MATERIAL DISCOGRAPHICAL & REFERENCE BOOKS, PAMPHLETS, BIOGRAPHIES; PROGRAMS Books Are All in Good, Used Condition (No Damage Unless Described)

PRINTED MATERIAL DISCOGRAPHICAL & REFERENCE BOOKS, PAMPHLETS, BIOGRAPHIES; PROGRAMS Books are all in good, used condition (no damage unless described). “As new” should be just that. “Excellent” would be similar to 2, light dust jacket or cover marks but no problems. “Good” would be similar to 3 (use wear). Any damage or marking is mentioned. DJ = includes Paper Dust Jacket “THE RECORD COLLECTOR” MAGAZINE Given below is the featured artist(s) of each issue (D=discography, B-biographical sketch). All copies are in fine condition (with the possibility of an index mark or possible check marks, occasional underlinings, but no physical damage such as tears, loose seams, etc., unless otherwise indicated. MINIMUM BID $5.00 PER MAGAZINE 8002. II/1-6. (Jan.-June, 1947). Re-issue of first half of Volume II, originally in mimeographed format. 8006. III/3. Götterdämmerung on Records; The Victor News Letter; American Record Notes, etc. 8007. III/4. Rethberg Discography; more Götterdämmerung; Cloe Elmo; Russian Operatic Discs, etc. 8010. III/7. Dating Victor Records; A Brief Glance Back; More “Historical Record” Amendments, etc. 8011. III/8. Iris addenda; Russian Operatic Records; More on Affre; The Aldeburgh Festival, etc. 8012. III/9. Edison Disc Records; Celebrities at Birmingham; Puccini Operas; More on Götterdämmerung, etc. 8013. III/10. A Santley Curiosity; Matrix & Serial Numbers; My Most Inartistic Recording; etc. 8015. III/12. Bauer Amendments; Italian Vocal Issues Jan.-Aug. 1948; Philadelphia Record Society, etc. 8017. IV/2. Giovanni Zenatello (D); “Otello” discography, etc. 8018. IV/3. Medea Mei-Figner (D); Another Curiosity; Italian Vocal Issues, etc. 8019. IV/4 The DeReszke Mystery; Eugenia Mantelli (D and commentary), To Help the Junior Collector, etc. -

Così Fan Tutte

1 La Fenice prima dell’Opera 2012 1 2012 Fondazione Stagione 2012 Teatro La Fenice di Venezia Lirica e Balletto Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart CosìFan osì fan tutte osì fan C Tutte ozart M madeus A olfgang olfgang W FONDAZIONE TEATRO LA FENICE DI VENEZIA TEATRO LA FENICE - pagina ufficiale seguici su facebook e twitter follow us on facebook and twitter Incontro con l’opera FONDAZIONE lunedì 16 gennaio 2012 ore 18.00 AMICI DELLA FENICE SANDRO CAPPELLETTO, MARIO MESSINIS, DINO VILLATICO STAGIONE 2012 Lou Salomé sabato 4 febbraio 2012 ore 18.00 MICHELE DALL’ONGARO L’inganno felice mercoledì 8 febbraio 2012 ore 18.00 LUCA MOSCA Così fan tutte martedì 6 marzo 2012 ore 18.00 LUCA DE FUSCO, GIANNI GARRERA L’opera da tre soldi martedì 17 aprile 2012 ore 18.00 LORENZO ARRUGA La sonnambula lunedì 23 aprile 2012 ore 18.00 PIER LUIGI PIZZI, PHILIP WALSH Powder Her Face giovedì 10 maggio 2012 ore 18.00 RICCARDO RISALITI La bohème lunedì 18 giugno 2012 ore 18.00 GUIDO ZACCAGNINI Carmen giovedì 5 luglio 2012 ore 18.00 MICHELE SUOZZO L’elisir d’amore giovedì 13 settembre 2012 ore 18.00 MASSIMO CONTIERO Clavicembalo francese a due manuali copia dello Rigoletto strumento di Goermans-Taskin, costruito attorno sabato 6 ottobre 2012 ore 18.00 alla metà del XVIII secolo (originale presso la Russell PHILIP GOSSETT Collection di Edimburgo). L’occasione fa il ladro Opera del M° cembalaro Luca Vismara di Seregno (MI); ultimato nel gennaio 1998. lunedì 5 novembre 2012 ore 18.00 Le decorazioni, la laccatura a tampone e le SERGIO COFFERATI chinoiseries – che sono espressione di gusto Otello tipicamente settecentesco per l’esotismo mercoledì 14 novembre 2012 ore 18.00 orientaleggiante, in auge soprattutto in ambito GIORGIO PESTELLI francese – sono state eseguite dal laboratorio dei fratelli Guido e Dario Tonoli di Meda (MI).