Language Problems in Applied Linguistics: Limiting the Scope

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Theoretical Linguistics, Vol

Edinburgh Research Explorer Action-based grammar Citation for published version: Kempson, R, Cann, R, Gregoromichelaki, E & Chatzikyriakidis, S 2017, 'Action-based grammar', Theoretical Linguistics, vol. 43, no. 1-2, pp. 141-167. https://doi.org/10.1515/tl-2017-0012 Digital Object Identifier (DOI): 10.1515/tl-2017-0012 Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Published In: Theoretical Linguistics General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 29. Sep. 2021 Theoretical Linguistics 2017; 43(1-2): 141–167 Ruth Kempson, Ronnie Cann, Eleni Gregoromichelaki and Stergios Chatzikyriakidis Action-Based Grammar DOI 10.1515/tl-2017-0012 1 Competence-performance and levels of description First of all we would like to thank the commentators for their efforts that resulted in thoughtful and significant comments about our account.1 We are delighted that the main thesis we presented – the inclusion of interactive language use within the remit of grammars – seems to have received an unexpected consensus from such diverse perspectives. -

Teaching (Theoretical) Linguistics in the Second Language Classroom: Beyond Language Improvement

PORTA LINGUARUM 22, junio 2014 161-171 Teaching (Theoretical) Linguistics in the Second Language Classroom: Beyond Language Improvement MAITE CORREA Colorado State University Received: 13 July 2012 / Accepted: 7 February 2013 ISSN: 1697-7467 ABSTRACT: Linguistics enjoys a paradoxical place in second language (SL) teaching. Un- like students majoring in Linguistics who see it as “study of the mind”, those who take it as part of a language degree see it as relevant as far as it supports language learning. However, a good command of the language is not sufficient for effective teaching. I address the need to revise the place of linguistics in SL curricula and present an innovative teaching approach that analyzes language in a scientific, systematic manner while focusing on those aspects of language that are of direct relevance to future language teachers. Keywords: Theoretical linguistics, pedagogy, teacher education, teacher learning, educa- tional linguistics. La enseñanza de lingüística (teórica) en la clase de ELE: más allá de la mejora comu- nicativa RESUMEN: La lingüística ocupa un lugar paradójico en los departamentos de didáctica de la lengua extranjera: aunque en los departamentos de Filología se ve como una “ventana a la mente”, en los de didáctica se ve como un apoyo al aprendizaje de la lengua por parte del futuro profesor. En este artículo reviso el lugar de la lingüística en el currículo de enseñan- za de segundas lenguas y presento un enfoque a la enseñanza de la lingüística que, siendo sistemático y científico, también se enfoca en aquellos aspectos relevantes para los futuros maestros de lengua extranjera. -

Linguistics in Applied Linguistics: a Historical Overview

JOURNAL OF ENGLISH STUDIES - VOLUME 3, (2001-2), 99-114 LINGUISTICS IN APPLIED LINGUISTICS: A HISTORICAL OVERVIEW TONY HARRIS University of Granada ABSTRACT. This paper looks at some of the underlying reasons which might explain the uncertainty surrounding applied linguistics as an academic enquiry. The opening section traces the emergence of the field through its professional associations and publications and identifies second and foreign language (L2) teaching as its primary activity. The succeeding section examines the extent to which L2 pedagogy, as a branch of applied linguistics, is conceived within a theoretical linguistic framework and how this might have changed during a historical period that gave rise to Chomskyan linguistics and the notion of communicative competence. The concluding remarks offer explanations to account for the persistence of linguistic parameters to define applied linguistics. 1. INTRODUCTION Perhaps the most difficult challenge facing the discipline of applied linguistics at the start of the new millennium is to define the ground on which it plies its trade. The field is not infrequently criticised and derided by the parent science, linguistics, which claims authority over academic terrain that applied linguists consider their own. It should be said, however, that applied linguists themselves seem to attract such adversity because of the lack of consensus within their own ranks about what it is they are actually engaged in. The elusiveness of a definition that might string together an academic domain of such wide-ranging diversity, which appears to be in a perennial state of expansion, makes definitions unsafe, not to say time-bound, and in this sense Widdowson’s (2000a: 3) likening of the field to “the Holy Roman Empire: a kind of convenient nominal fiction” is uncomfortably close to the 99 TONY HARRIS truth. -

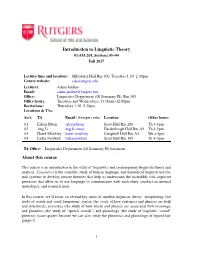

Introduction to Linguistic Theory About This Course

Introduction to Linguistic Theory 01:615:201, Sections 01–04 Fall 2017 Lecture time and location: Milledoler Hall Rm 100, Tuesdays 1:10–2:30pm Course website: sakai.rutgers.edu Lecturer: Adam Jardine Email: [email protected] Office: Linguistics Department (18 Seminary Pl), Rm 303 Office hours: Tuesdays and Wednesdays, 11:00am–12:00pm Recitations: Thursdays 1:10–2:30pm Locations & TAs: Sect. TA Email (@rutgers.edu) Location Office hours 01 EileenBlum eileen.blum ScottHallRm206 Th3-4pm 02 AngLi ang.li.aimee Hardenbergh Hall Rm A5 Th 4-5pm 03 Hazel Mitchley hazel.mitchley CampbellHallRmA3 We4-5pm 04 LydiaNewkirk lydia.newkirk ScottHallRm105 Tu4–5pm TA Office: Linguistics Department (18 Seminary Pl) basement About this course This course is an introduction to the study of linguistics and contemporary linguistic theory and analysis. Linguistics is the scientific study of human language, and theoretical linguists use for- mal systems to develop precise theories that help us understand the incredibly rich cognitive processes that allow us to use language to communicate with each other, conduct an internal monologue, and so much more. In this course, we’ll focus on several key areas of modern linguistic theory: morphology (the study of words and word formation), syntax (the study of how sentences and phrases are built and structured), semantics (the study of how words and phrases are associated with meaning), and phonetics (the study of “speech sounds”) and phonology (the study of linguistic “sound” patterns) (scare quotes because we can also study the phonetics and phonology of signed lan- guages!). 1 Jardine LING201syllabus 2 Course learning goals At the completion of this course, students will be able to: • Understand significant subfields within linguistics. -

Theoretical Linguistics 2016; 42(3-4): 291–296

Theoretical Linguistics 2016; 42(3-4): 291–296 Comments Gregory M. Kobele* and Jason Merchant The Dynamics of Ellipsis DOI 10.1515/tl-2016-0013 1 Introduction Kempson, Cann, Gregoromichelaki, and Chatzikyriakidis (henceforth KCGC) report on a theory of ellipsis in the idiom of Dynamic Syntax, and contrast it with other approaches. Underlying this contrast is the assumption that other grammatical traditions either must, or at least choose to, treat all sentence fragments as instances of ellipsis. This assumption is discussed further in Kobele (2016). We think that the question of whether to analyze a particular sentence fragment in terms of ellipsis should be influenced by empirical considerations. Standard diagnostics for the presence of ellipsis (as laid out for example in Merchant [2013b]) would not suggest that most of what is discussed is in fact elliptical. Fragments themselves come in many stripes, and some may have sentential sources (and thus be thought of as elliptical, such as fragment answers, as analyzed in Merchant [2004]), and many others may not (such as names, titles, and clarificational phrases, among the many others listed in Merchant [2010]). Merchant (2016) scrutinizes the fragments in KCGC from this perspective. We will not here attempt to undertake this work, but rather restrict our attention to cases such as VP-ellipsis or predicate ellipsis that all approaches agree form central ellip- tical explicanda. In this response we take a step back and focus on the basic idea on which KCGC’s theory of ellipsis is based. This fundamental idea is in fact shared by many of the approaches KCGC critique. -

The Complementarity Between Theoretical Linguistics, Neurolinguis Linguistic Portfolios–ISSN 2472-5102 –Volume 6, 2017 | 2

Linguistic Portfolios Volume 6 Article 2 2017 The ompleC mentarity between Theoretical Linguistics, Neurolinguistics, and Communication Sciences and Disorders Deanna Yoder-Black St. Cloud State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.stcloudstate.edu/stcloud_ling Part of the Applied Linguistics Commons Recommended Citation Yoder-Black, Deanna (2017) "The ompC lementarity between Theoretical Linguistics, Neurolinguistics, and Communication Sciences and Disorders," Linguistic Portfolios: Vol. 6 , Article 2. Available at: https://repository.stcloudstate.edu/stcloud_ling/vol6/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by theRepository at St. Cloud State. It has been accepted for inclusion in Linguistic Portfolios by an authorized editor of theRepository at St. Cloud State. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The ompleC mentarity between Theoretical Linguistics, Neurolinguistics, and Communication Sciences and Disorders Cover Page Footnote This paper was presented as the keynote address to the Minnesota Undergraduate Linguistics Symposium, held at St. Cloud State University, St. Cloud, MN, in April 2016. This article is available in Linguistic Portfolios: https://repository.stcloudstate.edu/stcloud_ling/vol6/iss1/2 Yoder-Black: The Complementarity between Theoretical Linguistics, Neurolinguis Linguistic Portfolios–ISSN 2472-5102 –Volume 6, 2017 | 2 THE COMPLEMENTARITY BETWEEN THEORETICAL LINGUISTICS, NEUROLINGUISTICS, AND COMMUNICATION SCIENCES AND DISORDERS DEANNA YODER-BLACK MS, CCC-SLP/L ABSTRACT As science evolves, there is an ever-increasing interplay between disciplines. In Communication Sciences and Disorders interdisciplinary theory is needed because of a number of factors such as the growing detail in imaging technology, the development of new strategies in the identification and the treatment of disease, and the nuances that arise in fields that have become more and more specialized. -

Theoretical Linguistics Introduction: Linguistics Is Defined As the Scientific Study of Language

People’s Democratic Republic of Algeria Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research Level: First year University of M’sila Teacher: Ms. BENSAID Module: Linguistics Faculty of Letters and Languages - Department of English Group : 04, 05 & 06 Lecture: Theoretical linguistics Introduction: Linguistics is defined as the scientific study of language. The word “ linguistics” was first used in the middle of the 19th C to underline the difference between a modern approach to language study that was then developing and a more traditional approach of philology. Philologists were concerned with the historical development of languages whereas linguists tends to give priority to spoken languages as well as to the problems of analyzing them as they operate at a given point in time. Linguistics can be devided into two main branches; applied linguistics and theoritical linguistics which is the main concern of this paper. I. Theoretical linguistics: Theoretical linguistics is the branch of linguistics that inquires into the nature of language or languages without regard for practical applications. It focuses on the examination of the structure of natural languages. The aim of theoretical linguistics is the construction of a general theory of the structure of language, or of a general theoretical framework for language description. "Briefly, theoretical linguistics studies language and languages with a view to constructing a theory of their structure and functions and without regard to any practical applications that the investigation of language and languages might have, whereas applied linguistics has as its concerns the application of the concepts and findings of linguistics to a variety of practical tasks, including language-teaching." (Lyons 1981:35). -

SKY Journal of Linguistics Is Published by the Linguistic Association of Finland (One Issue Per Year)

SKY Journal of Linguistics is published by the Linguistic Association of Finland (one issue per year). Notes for Contributors Policy: SKY Journal of Linguistics welcomes unpublished original works from authors of all nationalities and theoretical persuasions. Every manuscript is reviewed by at least two anonymous referees. In addition to full-length articles, the journal also accepts short (3-5 pages) ‘squibs’ as well as book reviews. Language of Publication: Contributions should be written in either English, French, or German. If the article is not written in the native language of the author, the language should be checked by a qualified native speaker. Style Sheet: A detailed style sheet is available from the editors, as well as via WWW at http://www.ling.helsinki.fi/sky/skystyle.shtml. Abstracts: Abstracts of the published papers are included in Linguistics Abstracts and Cambridge Scientific Abstracts. SKY JoL is also indexed in the MLA Bibliography. Editors’ Addresses (2005): Pentti Haddington, Department Finnish, Information Studies and Logopedics, P.O. Box 1000, FIN-90014 University of Oulu, Finland (e-mail [email protected]) Jouni Rostila, German Language and Culture Studies, FIN-33014 University of Tampere, Finland (e-mail [email protected]) Ulla Tuomarla, Department of Romance Languages, P.O. Box 24 (Unioninkatu 40B), FIN-00014 University of Helsinki, Finland (e-mail [email protected]) Publisher: The Linguistic Association of Finland c/o Department of Linguistics P.O. Box 4 FIN-00014 University of Helsinki Finland http://www.ling.helsinki.fi/sky The Linguistic Association of Finland was founded in 1977 to promote linguistic research in Finland by offering a forum for the discussion and dissemination of research in linguistics, both in Finland and abroad. -

Theoretical Comparative Syntax

Theoretical Comparative Syntax Theoretical Comparative Syntax brings together, for the first time, profoundly influential essays and articles by Naoki Fukui, exploring various topics in the areas of syntactic theory and comparative syntax. The articles have a special focus on the typological differences between English (-type lan- guages) and Japanese (-type languages) and abstract parameters that derive them. Linguistic universals are considered in the light of cross-linguistic variation, and typological (parametric) differences are investigated from the viewpoint of universal principles. The unifying theme of this volume is the nature and structure of invari- ant principles and parameters (variables) and how they interact to give prin- cipled accounts to a variety of seemingly unrelated differences between English and Japanese. These two types of languages provide an ideal testing ground for the principles and their interactions with the parameters since the languages exhibit diverse superficial differences in virtually every aspect of their linguistic structures: word order, wh-movement, grammatical agree- ment, the obligatoriness and uniqueness of a subject, complex predicates, case-marking systems, anaphoric systems, classifiers and numerals, among others. Detailed descriptions of the phenomena and attempts to provide principled accounts for them constitute considerable contributions to the development of the principles-and-parameters model in its exploration and refinement of theoretical concepts and fundamental principles of linguistic theory, leading to some of the basic insights that lie behind the minimalist program. The essays on theoretical comparative syntax collected here present a substantial contribution to the field of linguistics. Naoki Fukui is Professor of Linguistics and Chair of the Linguistics Department at Sophia University, Tokyo. -

Theoretical Linguistics 2016; 42(1-2): 173–201

Theoretical Linguistics 2016; 42(1-2): 173–201 Philippe Schlenker*, Emmanuel Chemla, Anne M. Schel, James Fuller, Jean-Pierre Gautier, Jeremy Kuhn, Dunja Veselinović, Kate Arnold, Cristiane Cäsar, Sumir Keenan, Alban Lemasson, Karim Ouattara, Robin Ryder and Klaus Zuberbühler Formal monkey linguistics: The debate DOI 10.1515/tl-2016-0010 Abstract: We explain why general techniques from formal linguistics can and should be applied to the analysis of monkey communication – in the areas of syntax and especially semantics. An informed look at our recent proposals shows that such techniques needn’t rely excessively on categories of human *Corresponding author: Philippe Schlenker, Département d’Etudes Cognitives, Ecole Normale Supérieure, Institut Jean-Nicod (ENS – EHESS – CNRS), Paris, France; PSL Research University, Paris, France; Department of Linguistics, New York University, New York, NY, USA, E-mail: [email protected] Emmanuel Chemla, PSL Research University, Paris, France; Département d’Etudes Cognitives, Ecole Normale Supérieure, Laboratoire de Sciences Cognitives et Psycholinguistique (ENS – EHESS – CNRS), Paris, France Anne M. Schel, Department of Animal Ecology, Utrecht University, Utrecht, The Netherlands James Fuller, Department of Ecology, Evolution and Environmental Biology, Columbia University, New York, NY, USA; New York Consortium in Evolutionary Primatology (NYCEP), New York, NY, USA; BCC, City University of New York, Bronx, NY, USA Jean-Pierre Gautier, CNRS, Station biologique de Paimpont, Université de Rennes -

Theoretical Linguistics-Linguistic Typology

THEORETICAL LINGUISTICS/LINGUISTIC TYPOLOGY Language-Cognition new Interface: State of the LINCOM Studies Art Vol. 05 in Phonetics RAMESH KUMAR MISHRA & NARAYANAN SRINIVASAN (eds.) Centre for Behavioural and Cognitive Experimental phonetics and sound change Science (CBCS), University of Allahabad Significant theoretical developments have taken DANIEL RECASENS, FERNANDO SÁNCHEZ MIRET place in language-cognition research in the last few decades. The collected chapters in this book & KENNETH J. WIREBACK (EDS.) provide extensive coverage of important areas of Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona; Universidad de Salamanca; Miami University this research domain including bilingualism, sentence processing, and embodied cognition. The chapters written by experts provide the This book gathers some contributions from scholars working on the phonetic and reader the most up to date discussion about issues phonological causes of sound change. Experimental evidence collected during the last and controversies while providing theoretical and decades calls for the need to build up better models of sound change which incorporate empirical knowledge about these themes. In spite evidence from articulatory strategies, acoustic variation and perceptual categorization of the wide range of topics covered, there has mechanisms. The papers collected in this book deal with the explanation of several sound been an attempt to make the collection thematically coherent providing the state of the changes, i.e., vowel shift and diphthongization, consonant voicing, assimilation, art in language-cognition research. palatalization, vocalization and retroflexion, and with specific arrangements of places of The chapters have been written for both articulation in sibilant inventories. researchers as well as graduate students interested in basic issues in language-cognition research and Contents: their relevance for larger issues on language and Silvia Calamai & Irene Ricci, «Speech rate and articulatory patterns in Italian nasal-velar clusters». -

Ling 70100, Introduction to Theoretical Linguistics Sam Al Khatib Fall 2021, Wednesday 11:45–1:45 PM, Room

Ling 70100, Introduction to Theoretical Linguistics Sam Al Khatib Fall 2021, Wednesday 11:45–1:45 PM, Room TBA [email protected] Office: Room 7400.02 Office hours: TBA Jason Kandybowicz [email protected] Office: Room 7400.05 Office hours: TBA Ling 73800, Practicum Alaa Sharif Fall 2021, Time and Room TBA [email protected] Course Description An introduction to the intellectual foundations, methods, and motivations of theoretical Linguistics. What kinds of questions do linguists ask? What do some of the answers look like? And why? The course will cover fundamental concepts in the core areas of theoretical Linguistics (Phonology, Morphology, Syntax, and Semantics). A substantial component of the course will be the discussion and demonstration of analytical techniques used in contemporary linguistics and applied to problem sets. A practicum (LING 73800) is attached to this course, taught by a graduate student teaching assistant. Course Goals Students in this course will gain a general understanding of the concerns, methods, and substance of the core subfields of theoretical Linguistics: Phonology, Morphology, Syntax, and Semantics. Students will become familiar with argumentation and analysis in these subfields. Learning Objectives Students in this course will gain familiarity with the terminology, core concepts, central questions, and prominent analytical tools of theoretical linguistic analysis. Upon completion of the course, students will be able to read primary theoretical literature and be prepared to take introductory level courses in linguistic theory. Class Topics and Reading Assignments Meeting Date Topics and Reading Assignments Syntax & Semantics Class 1 TBA Reading: Beck & Gergel 2014, Ch. 1; Radford 2004, Ch.