Linguistics in Applied Linguistics: a Historical Overview

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How to Get Published in ESOL and Applied Linguistics Serials

How to Get Published in TESOL and Applied Linguistics Serials TESOL Convention & Exhibit (TESOL 2016 Baltimore) Applied Linguistics Editor(s): John Hellermann & Anna Mauranen Editor/Journal E-mail: [email protected] Journal URL: http://applij.oxfordjournals.org/ Journal description: Applied Linguistics publishes research into language with relevance to real-world problems. The journal is keen to help make connections between fields, theories, research methods, and scholarly discourses, and welcomes contributions which critically reflect on current practices in applied linguistic research. It promotes scholarly and scientific discussion of issues that unite or divide scholars in applied linguistics. It is less interested in the ad hoc solution of particular problems and more interested in the handling of problems in a principled way by reference to theoretical studies. Applied linguistics is viewed not only as the relation between theory and practice, but also as the study of language and language-related problems in specific situations in which people use and learn languages. Within this framework the journal welcomes contributions in such areas of current enquiry as: bilingualism and multilingualism; computer-mediated communication; conversation analysis; corpus linguistics; critical discourse analysis; deaf linguistics; discourse analysis and pragmatics; first and additional language learning, teaching, and use; forensic linguistics; language assessment; language planning and policies; language for special purposes; lexicography; literacies; multimodal communication; rhetoric and stylistics; and translation. The journal welcomes both reports of original research and conceptual articles. The Journal’s Forum section is intended to enhance debate between authors and the wider community of applied linguists (see Editorial in 22/1) and affords a quicker turnaround time for short pieces. -

Theoretical Linguistics, Vol

Edinburgh Research Explorer Action-based grammar Citation for published version: Kempson, R, Cann, R, Gregoromichelaki, E & Chatzikyriakidis, S 2017, 'Action-based grammar', Theoretical Linguistics, vol. 43, no. 1-2, pp. 141-167. https://doi.org/10.1515/tl-2017-0012 Digital Object Identifier (DOI): 10.1515/tl-2017-0012 Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Published In: Theoretical Linguistics General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 29. Sep. 2021 Theoretical Linguistics 2017; 43(1-2): 141–167 Ruth Kempson, Ronnie Cann, Eleni Gregoromichelaki and Stergios Chatzikyriakidis Action-Based Grammar DOI 10.1515/tl-2017-0012 1 Competence-performance and levels of description First of all we would like to thank the commentators for their efforts that resulted in thoughtful and significant comments about our account.1 We are delighted that the main thesis we presented – the inclusion of interactive language use within the remit of grammars – seems to have received an unexpected consensus from such diverse perspectives. -

Why Major in Linguistics (And What Does a Linguist Do)? by Monica Macaulay and Kristen Syrett

1 Why Major in Linguistics (and what does a linguist do)? by Monica Macaulay and Kristen Syrett What is linguistics? Speakers of all languages know a lot about their languages, usually without knowing that they know If you are considering becoming a linguistics it. For example, as a speaker of English, you major, you probably know something about the possess knowledge about English word order. field of linguistics already. However, you may find Perhaps without even knowing it, you understand it hard to answer people who ask you, "What that Sarah admires the teacher is grammatical, exactly is linguistics, and what does a linguist do?" while Admires Sarah teacher the is not, and also They might assume that it means you speak a lot of that The teacher admires Sarah means something languages. And they may be right: you may, in entirely different. You know that when you ask a fact, be a polyglot! But while many linguists do yes-no question, you may reverse the order of speak multiple languages—or at least know a fair words at the beginning of the sentence and that the bit about multiple languages—the study of pitch of your voice goes up at the end of the linguistics means much more than this. sentence (for example, in Are you going?). Linguistics is the scientific study of language, and However, if you speak French, you might add est- many topics are studied under this umbrella. At the ce que at the beginning, and if you know American heart of linguistics is the search for the unconscious knowledge that humans have about language and how it is that children acquire it, an understanding of the structure of language in general and of particular languages, knowledge about how languages vary, and how language influences the way in which we interact with each other and think about the world. -

September 2009 Special Edition Language, Culture and Identity in Asia

The Linguistics Journal – September 2009 The Linguistics Journal September 2009 Special Edition Language, Culture and Identity in Asia Editors: Francesco Cavallaro, Andrea Milde, & Peter Sercombe The Linguistics Journal – Special Edition Page 1 The Linguistics Journal – September 2009 The Linguistics Journal September 2009 Special Edition Language, Culture and Identity in Asia Editors: Francesco Cavallaro, Andrea Milde, & Peter Sercombe The Linguistics Journal: Special Edition Published by the Linguistics Journal Press Linguistics Journal Press A Division of Time Taylor International Ltd Trustnet Chambers P.O. Box 3444 Road Town, Tortola British Virgin Islands http://www.linguistics-journal.com © Linguistics Journal Press 2009 This E-book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of the Linguistics Journal Press. No unauthorized photocopying All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior written permission of The Linguistics Journal. [email protected] Editors: Francesco Cavallaro, Andrea Milde, & Peter Sercombe Senior Associate Editor: Katalin Egri Ku-Mesu Journal Production Editor: Benjamin Schmeiser ISSN 1738-1460 The Linguistics Journal – Special Edition Page 2 The Linguistics Journal – September 2009 Table of Contents Foreword by Francesco Cavallaro, Andrea Milde, & Peter Sercombe………………………...... 4 - 7 1. Will Baker……………………………………………………………………………………… 8 - 35 -Language, Culture and Identity through English as a Lingua Franca in Asia: Notes from the Field 2. Ruth M.H. Wong …………………………………………………………………………….. 36 - 62 -Identity Change: Overseas Students Returning to Hong Kong 3. Jules Winchester……………………………………..………………………………………… 63 - 81 -The Self Concept, Culture and Cultural Identity: An Examination of the Verbal Expression of the Self Concept in an Intercultural Context 4. -

Teaching (Theoretical) Linguistics in the Second Language Classroom: Beyond Language Improvement

PORTA LINGUARUM 22, junio 2014 161-171 Teaching (Theoretical) Linguistics in the Second Language Classroom: Beyond Language Improvement MAITE CORREA Colorado State University Received: 13 July 2012 / Accepted: 7 February 2013 ISSN: 1697-7467 ABSTRACT: Linguistics enjoys a paradoxical place in second language (SL) teaching. Un- like students majoring in Linguistics who see it as “study of the mind”, those who take it as part of a language degree see it as relevant as far as it supports language learning. However, a good command of the language is not sufficient for effective teaching. I address the need to revise the place of linguistics in SL curricula and present an innovative teaching approach that analyzes language in a scientific, systematic manner while focusing on those aspects of language that are of direct relevance to future language teachers. Keywords: Theoretical linguistics, pedagogy, teacher education, teacher learning, educa- tional linguistics. La enseñanza de lingüística (teórica) en la clase de ELE: más allá de la mejora comu- nicativa RESUMEN: La lingüística ocupa un lugar paradójico en los departamentos de didáctica de la lengua extranjera: aunque en los departamentos de Filología se ve como una “ventana a la mente”, en los de didáctica se ve como un apoyo al aprendizaje de la lengua por parte del futuro profesor. En este artículo reviso el lugar de la lingüística en el currículo de enseñan- za de segundas lenguas y presento un enfoque a la enseñanza de la lingüística que, siendo sistemático y científico, también se enfoca en aquellos aspectos relevantes para los futuros maestros de lengua extranjera. -

Introduction to Linguistic Theory About This Course

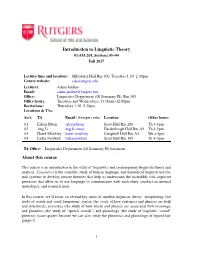

Introduction to Linguistic Theory 01:615:201, Sections 01–04 Fall 2017 Lecture time and location: Milledoler Hall Rm 100, Tuesdays 1:10–2:30pm Course website: sakai.rutgers.edu Lecturer: Adam Jardine Email: [email protected] Office: Linguistics Department (18 Seminary Pl), Rm 303 Office hours: Tuesdays and Wednesdays, 11:00am–12:00pm Recitations: Thursdays 1:10–2:30pm Locations & TAs: Sect. TA Email (@rutgers.edu) Location Office hours 01 EileenBlum eileen.blum ScottHallRm206 Th3-4pm 02 AngLi ang.li.aimee Hardenbergh Hall Rm A5 Th 4-5pm 03 Hazel Mitchley hazel.mitchley CampbellHallRmA3 We4-5pm 04 LydiaNewkirk lydia.newkirk ScottHallRm105 Tu4–5pm TA Office: Linguistics Department (18 Seminary Pl) basement About this course This course is an introduction to the study of linguistics and contemporary linguistic theory and analysis. Linguistics is the scientific study of human language, and theoretical linguists use for- mal systems to develop precise theories that help us understand the incredibly rich cognitive processes that allow us to use language to communicate with each other, conduct an internal monologue, and so much more. In this course, we’ll focus on several key areas of modern linguistic theory: morphology (the study of words and word formation), syntax (the study of how sentences and phrases are built and structured), semantics (the study of how words and phrases are associated with meaning), and phonetics (the study of “speech sounds”) and phonology (the study of linguistic “sound” patterns) (scare quotes because we can also study the phonetics and phonology of signed lan- guages!). 1 Jardine LING201syllabus 2 Course learning goals At the completion of this course, students will be able to: • Understand significant subfields within linguistics. -

Language Teaching and Educational Research E-ISSN 2636-8102 Volume 2, Issue 2 | 2019

Language Teaching and Educational Research e-ISSN 2636-8102 Volume 2, Issue 2 | 2019 Reading Comprehension and Vocabulary Size of CLIL and Non-CLIL Students: A Comparative Study Dilan Bayram Rukiye Özlem Öztürk Derin Atay To cite this article: Bayram, D., Öztürk, R. Ö., & Atay, D. (2019). Reading comprehension and vocabulary size of CLIL and non-CLIL students: A comparative study. Language Teaching and Educational Research (LATER), 2(2), 101-113. DOI: https://doi.org/10.35207/later.639337 View the journal website Submit your article to LATER Contact editor Copyright (c) 2019 LATER and the author(s). This is an open access article under CC BY-NC-ND license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/) Language Teaching and Educational Research e-ISSN: 2636-8102 LATER, 2019: 2(2), 101-113 http://dergipark.org.tr/later Research Article Reading comprehension and vocabulary size of CLIL and non-CLIL students: A comparative study Dilan Bayram1 Research Assistant, Marmara University, Department of English Language Teaching, TURKEY Rukiye Özlem Öztürk2 Lecturer, Bahçeşehir University, Department of English Language Teaching, TURKEY Derin Atay3 Professor, Bahçeşehir University, Department of English Language Teaching, TURKEY Abstract Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL) has a dual focus both on content and language teaching in which students learn through and about language and Received provides contextualized and meaningful situations. Although studies on the impact 28 October 2019 of CLIL on learners’ vocabulary knowledge and reading comprehension have mostly Accepted positive results, related research is highly limited in Turkish context. Thus, this study 02 December 2019 aims to examine to what extent CLIL students differ from non-CLIL students in terms of their reading comprehension and vocabulary size (i.e. -

Theoretical Linguistics 2016; 42(3-4): 291–296

Theoretical Linguistics 2016; 42(3-4): 291–296 Comments Gregory M. Kobele* and Jason Merchant The Dynamics of Ellipsis DOI 10.1515/tl-2016-0013 1 Introduction Kempson, Cann, Gregoromichelaki, and Chatzikyriakidis (henceforth KCGC) report on a theory of ellipsis in the idiom of Dynamic Syntax, and contrast it with other approaches. Underlying this contrast is the assumption that other grammatical traditions either must, or at least choose to, treat all sentence fragments as instances of ellipsis. This assumption is discussed further in Kobele (2016). We think that the question of whether to analyze a particular sentence fragment in terms of ellipsis should be influenced by empirical considerations. Standard diagnostics for the presence of ellipsis (as laid out for example in Merchant [2013b]) would not suggest that most of what is discussed is in fact elliptical. Fragments themselves come in many stripes, and some may have sentential sources (and thus be thought of as elliptical, such as fragment answers, as analyzed in Merchant [2004]), and many others may not (such as names, titles, and clarificational phrases, among the many others listed in Merchant [2010]). Merchant (2016) scrutinizes the fragments in KCGC from this perspective. We will not here attempt to undertake this work, but rather restrict our attention to cases such as VP-ellipsis or predicate ellipsis that all approaches agree form central ellip- tical explicanda. In this response we take a step back and focus on the basic idea on which KCGC’s theory of ellipsis is based. This fundamental idea is in fact shared by many of the approaches KCGC critique. -

Applied Linguistics?

What is Applied Linguistics? Anne Burns ~ Wini Davies ~ Zoltán Dörnyei ~ Phil Durrant ~ Juliane House Richard Hudson ~ Susan Hunston ~ Andy Kirkpatrick ~ Dawn Knight ~ Jack C. Richards Applied linguistics is notoriously hard to define. What sets it apart from other areas of linguistics? How has it evolved over the years? What do applied linguists do? We asked ten leading and up-and-coming academics to give us their answer to the question: ‘What is applied linguistics?’ Below are their responses. Take a look at them and then add to the debate by sending us your definition. Of course, several commentators have offered definitions of applied linguistics in recent decades, including Crystal (1980: 20), Richards et al, (1985: 29), Brumfit (1995: 27) and Rampton (1997: 11). For me, applied linguistics means taking language and language theories as the basis from which to elucidate how communication is actually carried out in real life, to identify problematic or challenging issues involving language in many different contexts, and to analyse them in order to draw out practical insights and implications that are useful for the people in those contexts. As an applied linguist, I’m primarily interested in offering people practical and illuminating insights into how language and communication contribute fundamentally to interaction between people. Anne Burns Professor in the Faculty of Human Sciences, Macquarie University, Sydney © Cambridge University Press 2009 1 www.cambridge.org/elt A wit once described an applied linguist as someone with a degree in linguistics who was unable to get a job in a linguistics department. More seriously, looking back at the term ‘applied linguistics’, it first emerged as an attempt to provide a theoretical basis for the activities of language teaching (witness Pit Corder’s book on the subject from 1973). -

The Complementarity Between Theoretical Linguistics, Neurolinguis Linguistic Portfolios–ISSN 2472-5102 –Volume 6, 2017 | 2

Linguistic Portfolios Volume 6 Article 2 2017 The ompleC mentarity between Theoretical Linguistics, Neurolinguistics, and Communication Sciences and Disorders Deanna Yoder-Black St. Cloud State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.stcloudstate.edu/stcloud_ling Part of the Applied Linguistics Commons Recommended Citation Yoder-Black, Deanna (2017) "The ompC lementarity between Theoretical Linguistics, Neurolinguistics, and Communication Sciences and Disorders," Linguistic Portfolios: Vol. 6 , Article 2. Available at: https://repository.stcloudstate.edu/stcloud_ling/vol6/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by theRepository at St. Cloud State. It has been accepted for inclusion in Linguistic Portfolios by an authorized editor of theRepository at St. Cloud State. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The ompleC mentarity between Theoretical Linguistics, Neurolinguistics, and Communication Sciences and Disorders Cover Page Footnote This paper was presented as the keynote address to the Minnesota Undergraduate Linguistics Symposium, held at St. Cloud State University, St. Cloud, MN, in April 2016. This article is available in Linguistic Portfolios: https://repository.stcloudstate.edu/stcloud_ling/vol6/iss1/2 Yoder-Black: The Complementarity between Theoretical Linguistics, Neurolinguis Linguistic Portfolios–ISSN 2472-5102 –Volume 6, 2017 | 2 THE COMPLEMENTARITY BETWEEN THEORETICAL LINGUISTICS, NEUROLINGUISTICS, AND COMMUNICATION SCIENCES AND DISORDERS DEANNA YODER-BLACK MS, CCC-SLP/L ABSTRACT As science evolves, there is an ever-increasing interplay between disciplines. In Communication Sciences and Disorders interdisciplinary theory is needed because of a number of factors such as the growing detail in imaging technology, the development of new strategies in the identification and the treatment of disease, and the nuances that arise in fields that have become more and more specialized. -

Theoretical Linguistics Introduction: Linguistics Is Defined As the Scientific Study of Language

People’s Democratic Republic of Algeria Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research Level: First year University of M’sila Teacher: Ms. BENSAID Module: Linguistics Faculty of Letters and Languages - Department of English Group : 04, 05 & 06 Lecture: Theoretical linguistics Introduction: Linguistics is defined as the scientific study of language. The word “ linguistics” was first used in the middle of the 19th C to underline the difference between a modern approach to language study that was then developing and a more traditional approach of philology. Philologists were concerned with the historical development of languages whereas linguists tends to give priority to spoken languages as well as to the problems of analyzing them as they operate at a given point in time. Linguistics can be devided into two main branches; applied linguistics and theoritical linguistics which is the main concern of this paper. I. Theoretical linguistics: Theoretical linguistics is the branch of linguistics that inquires into the nature of language or languages without regard for practical applications. It focuses on the examination of the structure of natural languages. The aim of theoretical linguistics is the construction of a general theory of the structure of language, or of a general theoretical framework for language description. "Briefly, theoretical linguistics studies language and languages with a view to constructing a theory of their structure and functions and without regard to any practical applications that the investigation of language and languages might have, whereas applied linguistics has as its concerns the application of the concepts and findings of linguistics to a variety of practical tasks, including language-teaching." (Lyons 1981:35). -

Language Description and Linguistic Typology Fernando Zúñiga

Language description and linguistic typology Fernando Zúñiga 1. Introduction The past decade has seen not only a renewed interest in field linguistics and the description of lesser-known and endangered languages, but also the appearance of the more comprehensive undertaking of language documen- tation as a research field in its own right. Parallel to this, the study of lin- guistic diversity has noticeably evolved, turning into a complex and sophis- ticated field. The development of these two intellectual endeavors is mainly due to an increasing awareness of both the severity of language endanger- ment and the theoretical significance of linguistic diversity, and it has bene- fited from a remarkable improvement of computing hardware and software, as well as from several simultaneous developments in the worldwide avail- ability and use of information technologies. The important recent development of these two subfields of linguistics has certainly not gone unnoticed in the literature. When addressing the relationship between them, however, most scholars have concentrated on how and how much typology depends on the data provided by descriptive work, as well as on the usefulness and importance of typologically in- formed descriptions (cf. e.g. Croft 2003, Epps 2011, and the references therein). Rather than replicating articles that deal with historical issues and questions raised by the results of descriptive and typological enterprises, the present paper focuses on methodological issues raised by their respec- tive objects of study and emphasizes the relevance of some challenges they face. The different sections address the descriptivist’s activity (§2), the typologist’s job (§3), and some selected challenges on the road ahead for the two subfields and their cooperation (§4).