Theoretical Linguistics, Vol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How to Do Things with Types⇤

Joint Proceedings NLCS’14 & NLSR 2014, July 17-18, 2014, Vienna, Austria How to do things with types⇤ Robin Cooper University of Gothenburg Abstract We present a theory of type acts based on type theory relating to a general theory of action which can be used as a foundation for a theory of linguistic acts. Contents 1 Introduction 1 2 Type acts 2 3 Coordinating interaction in games 5 4 Conclusion 9 1 Introduction The title of this paper picks up, of course, on the seminal book How to do things with words by J.L. Austin [Aus62], which laid the foundation for speech act theory. In recent work on dialogue such as [Gin12] it is proposed that it is important for linguistic analysis to take seriously a notion of linguistic acts. To formulate this, Ginzburg uses TTR (“Type Theory with Records”) as developed in [Coo12]. The idea was also very much a part of the original work on situation semantics [BP83] which has also served as an inspiration for the work on TTR. TTR was also originally inspired by work on constructive type theory [ML84, NPS90] in which there is a notion of judgement that an object a is of a type T , a : T .1 We shall think of judgements as a kind of type act and propose that there are other type acts in addition to judgements. We shall also follow [Ran94] in including types of events (or more generally, situations) in a type theory suitable for building a theory of action and of linguistic meaning. ⇤The work for this paper was supported in part by VR project 2009-1569, SAICD. -

Department of Philosophy, Linguistics and Theory of Science on 2018-01-25 to Be Valid from 2018-01-25

DEPARTMENT OF PHILOSOPHY, LINGUISTICS AND THEORY OF SCIENCE Type Theory with Records: From Perception to Communication, 7,5 higher education credits Type Theory with Records: Från perception till kommunikation, 7,5 högskolepoäng Third Cycle/Forskarnivå Confirmation The course syllabus was confirmed by the Department of Philosophy, Linguistics and Theory of Science on 2018-01-25 to be valid from 2018-01-25. Entry requirements General and specific entry requirements for third-cycle education according to Admissions Regulations and the general syllabus for the subject area at hand. Learning outcomes After completion of the course the doctoral student is expected to be able to : Knowledge and understanding demonstrate enhanced knowledge and understanding of the subject areas of the course, discuss in detail key theories and issues in one or more of the subject areas of the course, Skills and abilities offer a detailed analysis of issues, lines of arguments or methods from the literature, select and define issues, lines of arguments or methods from the literature that are suitable for a short critical essay or a conference paper, Judgement and approach critically discuss, orally or in writing, questions, lines of arguments or methods that are used in the literature, critically assess the validity of the studied lines of argument. Course content The course introduces TTR, a Type Theory with Records, as a framework for natural language grammar and interaction. We are taking a dialogical view of semantics. The course covers the formal foundations of TTR as well as TTR accounts of perception, intensionality, information exchange, grammar (syntax and semantics), quantification, modality and other linguistic phenomena. -

Witness-Loaded and Witness-Free Demonstratives

Witness-loaded and Witness-free Demonstratives Andy Lücking Goethe University Frankfurt, Germany To Appear 2017 Prefinal draft, cite only full chapter Abstract According to current theories of demonstratives, both discourse referentially (en- dophoric) and real-world referentially (exophoric) uses of demonstrative noun phrases (DemNPs) obey the same mode of reference. Based on the clarification potential of DemNPs and on data on bridging and deferred reference it is argued that only ex- ophoric DemNPs allow for the identification of a demonstratum, while endophoric ones do not. Furthermore, the view that discourse reference does not involve a demonstration act is taken and, hence, contrary to standard assumption, the claim is made that both uses follow different modes of reference. In order to maintain a unified analysis of DemNPs, it is argued to spell out their semantics in terms of a grammar-dialog interface, where demonstratives and demonstration acts contribute to processing instructions for reference management. In this system, exophoric Dem- NPs are modeled as witness-loaded referential expressions, while endophoric Dem- NPs remain witness-free. A final claim is that the witness gives rise to manifold perceptual classifications, which in turn license indirect reference. The analysis is implemented in Type Theory with Records (which provides the notion of a witness) within Ginzburg’s dialog framework called KoS. The dynamics of demonstratives is captured by a set of rules that govern their processing in dialog. Keywords: demonstratives, demonstration, reference, deferred reference, wit- nesses, dialog 1 Introduction Demonstrative noun phrases (DemNPs) like this painting can be used in two ways: exophorically and endophorically (the latter can be further distinguished into anaphoric and cataphoric). -

Teaching (Theoretical) Linguistics in the Second Language Classroom: Beyond Language Improvement

PORTA LINGUARUM 22, junio 2014 161-171 Teaching (Theoretical) Linguistics in the Second Language Classroom: Beyond Language Improvement MAITE CORREA Colorado State University Received: 13 July 2012 / Accepted: 7 February 2013 ISSN: 1697-7467 ABSTRACT: Linguistics enjoys a paradoxical place in second language (SL) teaching. Un- like students majoring in Linguistics who see it as “study of the mind”, those who take it as part of a language degree see it as relevant as far as it supports language learning. However, a good command of the language is not sufficient for effective teaching. I address the need to revise the place of linguistics in SL curricula and present an innovative teaching approach that analyzes language in a scientific, systematic manner while focusing on those aspects of language that are of direct relevance to future language teachers. Keywords: Theoretical linguistics, pedagogy, teacher education, teacher learning, educa- tional linguistics. La enseñanza de lingüística (teórica) en la clase de ELE: más allá de la mejora comu- nicativa RESUMEN: La lingüística ocupa un lugar paradójico en los departamentos de didáctica de la lengua extranjera: aunque en los departamentos de Filología se ve como una “ventana a la mente”, en los de didáctica se ve como un apoyo al aprendizaje de la lengua por parte del futuro profesor. En este artículo reviso el lugar de la lingüística en el currículo de enseñan- za de segundas lenguas y presento un enfoque a la enseñanza de la lingüística que, siendo sistemático y científico, también se enfoca en aquellos aspectos relevantes para los futuros maestros de lengua extranjera. -

Linguistics in Applied Linguistics: a Historical Overview

JOURNAL OF ENGLISH STUDIES - VOLUME 3, (2001-2), 99-114 LINGUISTICS IN APPLIED LINGUISTICS: A HISTORICAL OVERVIEW TONY HARRIS University of Granada ABSTRACT. This paper looks at some of the underlying reasons which might explain the uncertainty surrounding applied linguistics as an academic enquiry. The opening section traces the emergence of the field through its professional associations and publications and identifies second and foreign language (L2) teaching as its primary activity. The succeeding section examines the extent to which L2 pedagogy, as a branch of applied linguistics, is conceived within a theoretical linguistic framework and how this might have changed during a historical period that gave rise to Chomskyan linguistics and the notion of communicative competence. The concluding remarks offer explanations to account for the persistence of linguistic parameters to define applied linguistics. 1. INTRODUCTION Perhaps the most difficult challenge facing the discipline of applied linguistics at the start of the new millennium is to define the ground on which it plies its trade. The field is not infrequently criticised and derided by the parent science, linguistics, which claims authority over academic terrain that applied linguists consider their own. It should be said, however, that applied linguists themselves seem to attract such adversity because of the lack of consensus within their own ranks about what it is they are actually engaged in. The elusiveness of a definition that might string together an academic domain of such wide-ranging diversity, which appears to be in a perennial state of expansion, makes definitions unsafe, not to say time-bound, and in this sense Widdowson’s (2000a: 3) likening of the field to “the Holy Roman Empire: a kind of convenient nominal fiction” is uncomfortably close to the 99 TONY HARRIS truth. -

Introduction to Linguistic Theory About This Course

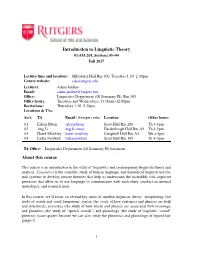

Introduction to Linguistic Theory 01:615:201, Sections 01–04 Fall 2017 Lecture time and location: Milledoler Hall Rm 100, Tuesdays 1:10–2:30pm Course website: sakai.rutgers.edu Lecturer: Adam Jardine Email: [email protected] Office: Linguistics Department (18 Seminary Pl), Rm 303 Office hours: Tuesdays and Wednesdays, 11:00am–12:00pm Recitations: Thursdays 1:10–2:30pm Locations & TAs: Sect. TA Email (@rutgers.edu) Location Office hours 01 EileenBlum eileen.blum ScottHallRm206 Th3-4pm 02 AngLi ang.li.aimee Hardenbergh Hall Rm A5 Th 4-5pm 03 Hazel Mitchley hazel.mitchley CampbellHallRmA3 We4-5pm 04 LydiaNewkirk lydia.newkirk ScottHallRm105 Tu4–5pm TA Office: Linguistics Department (18 Seminary Pl) basement About this course This course is an introduction to the study of linguistics and contemporary linguistic theory and analysis. Linguistics is the scientific study of human language, and theoretical linguists use for- mal systems to develop precise theories that help us understand the incredibly rich cognitive processes that allow us to use language to communicate with each other, conduct an internal monologue, and so much more. In this course, we’ll focus on several key areas of modern linguistic theory: morphology (the study of words and word formation), syntax (the study of how sentences and phrases are built and structured), semantics (the study of how words and phrases are associated with meaning), and phonetics (the study of “speech sounds”) and phonology (the study of linguistic “sound” patterns) (scare quotes because we can also study the phonetics and phonology of signed lan- guages!). 1 Jardine LING201syllabus 2 Course learning goals At the completion of this course, students will be able to: • Understand significant subfields within linguistics. -

Modelling Language, Action, and Perception in Type Theory with Records

Modelling Language, Action, and Perception in Type Theory with Records Simon Dobnik, Robin Cooper, and Staffan Larsson Department of Philosophy, Linguistics and Theory of Science University of Gothenburg, Box 200, 405 30 G¨oteborg, Sweden [email protected], {staffan.larsson,robin.cooper}@ling.gu.se http://www.flov.gu.se Abstract. Formal models of natural language semantics using TTR (Type Theory with Records) attempt to relate natural language to per- ception, modelled as classification of objects and events by types which are available as resources to an agent. We argue that this is better suited for representing the meaning of spatial descriptions in the context of agent modelling than traditional formal semantic models which do not relate spatial concepts to perceptual apparatus. Spatial descriptions in- clude perceptual, conceptual and discourse knowledge which we represent all in a single framework. Being a general framework for modelling both linguistic and non-linguistic cognition, TTR is more suitable for the mod- elling of situated conversational agents in robotics and virtual environ- ments where interoperability between language, action and perception is required. The perceptual systems gain access to abstract conceptual meaning representations of language while the latter can be justified in action and perception. Keywords: language, action, perception, formal semantics, spatial de- scriptions, learning and classification. 1 Introduction Classical model-theoretic semantics [1] does not deal with the connection be- tween linguistic meaning and perception or action. It does not provide a theory of non-linguistic perception and it is not obvious how to extend it to take account of this. Another feature of classical approaches to model theory is that they treat natural language as being essentially similar to formal languages in, among other things, assuming that there is a fixed interpretation function which mediates be- tween natural language and the world. -

Theoretical Linguistics 2016; 42(3-4): 291–296

Theoretical Linguistics 2016; 42(3-4): 291–296 Comments Gregory M. Kobele* and Jason Merchant The Dynamics of Ellipsis DOI 10.1515/tl-2016-0013 1 Introduction Kempson, Cann, Gregoromichelaki, and Chatzikyriakidis (henceforth KCGC) report on a theory of ellipsis in the idiom of Dynamic Syntax, and contrast it with other approaches. Underlying this contrast is the assumption that other grammatical traditions either must, or at least choose to, treat all sentence fragments as instances of ellipsis. This assumption is discussed further in Kobele (2016). We think that the question of whether to analyze a particular sentence fragment in terms of ellipsis should be influenced by empirical considerations. Standard diagnostics for the presence of ellipsis (as laid out for example in Merchant [2013b]) would not suggest that most of what is discussed is in fact elliptical. Fragments themselves come in many stripes, and some may have sentential sources (and thus be thought of as elliptical, such as fragment answers, as analyzed in Merchant [2004]), and many others may not (such as names, titles, and clarificational phrases, among the many others listed in Merchant [2010]). Merchant (2016) scrutinizes the fragments in KCGC from this perspective. We will not here attempt to undertake this work, but rather restrict our attention to cases such as VP-ellipsis or predicate ellipsis that all approaches agree form central ellip- tical explicanda. In this response we take a step back and focus on the basic idea on which KCGC’s theory of ellipsis is based. This fundamental idea is in fact shared by many of the approaches KCGC critique. -

Reference and Perceptual Memory in Situated Dialog

Referring to the recently seen: reference and perceptual memory in situated dialog John D. Kelleher Simon Dobnik ADAPT Research Centre CLASP and FLOV ICE Research Institute University of Gotenburg, Sweden Technological University Dublin [email protected] [email protected] Abstract From theoretical linguistic and cognitive perspectives, situated dialog systems are interesting as they provide ideal test-beds for investigating the interaction between language and perception. At the same time there are a growing number of practical applications, for example robotic systems and driver-less cars, where spoken interfaces, capable of situated dialog, promise many advantages. To date, however much of the work on situated dialog has focused resolving anaphoric or exophoric references. This paper, by con- trast, opens up the question of how perceptual memory and linguistic refer- ences interact, and the challenges that this poses to computational models of perceptually grounded dialog. 1 Introduction Situated language is spoken from a particular point of view within a shared per- ceptual context [6]. In an era where we are witnessing a proliferation of sensors that enable computer systems to perceive the world, effective computational mod- els of situated dialog have a growing number of practical applications, consider applications in human-robot interaction in personal assistants, driver-less car inter- faces that allow interaction with a passenger in language , and so on. From a more fundamental science perspective, computational models of situated dialog provide arXiv:1903.09866v1 [cs.HC] 23 Mar 2019 a test-bed for theories of cognition and language, in particular those dealing with the binding/fusion of language and perception in the interactive setting involving human conversational partners and ever-changing environment. -

Mass/Count Variation: a Mereological, Two-Dimensional Semantics

Baltic International Yearbook of Cognition, Logic and Communication Volume 11 Number: Cognitive, Semantic and Crosslinguistic Approaches Article 11 2016 Mass/Count Variation: A Mereological, Two-Dimensional Semantics Peter R. Sutton Heinrich Heine University Düsseldorf, Germany Hana Filip Heinrich Heine University Düsseldorf, Germany Follow this and additional works at: https://newprairiepress.org/biyclc Part of the Semantics and Pragmatics Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Sutton, Peter R. and Filip, Hana (2016) "Mass/Count Variation: A Mereological, Two-Dimensional Semantics," Baltic International Yearbook of Cognition, Logic and Communication: Vol. 11. https://doi.org/ 10.4148/1944-3676.1110 This Proceeding of the Symposium for Cognition, Logic and Communication is brought to you for free and open access by the Conferences at New Prairie Press. It has been accepted for inclusion in Baltic International Yearbook of Cognition, Logic and Communication by an authorized administrator of New Prairie Press. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Mass/Count Variation 2 The Baltic International Yearbook of The other index is a precisification index (inspired by Chierchia 2010). Cognition, Logic and Communication At some precisifications, the set of entities that count as ‘one’ can be excluded from a noun’s denotation leading to mass encoding. We com- December 2016 Volume 11: Number: Cognitive, Semantic and bine these indices into a two dimensional semantics that not only mod- Crosslinguistic Approaches els the semantics of a number of classes of nouns, but can also explain pages 1-45 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.4148/1944-3676.1110 and predict the puzzling phenomenon of mass/count variation. -

The Complementarity Between Theoretical Linguistics, Neurolinguis Linguistic Portfolios–ISSN 2472-5102 –Volume 6, 2017 | 2

Linguistic Portfolios Volume 6 Article 2 2017 The ompleC mentarity between Theoretical Linguistics, Neurolinguistics, and Communication Sciences and Disorders Deanna Yoder-Black St. Cloud State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.stcloudstate.edu/stcloud_ling Part of the Applied Linguistics Commons Recommended Citation Yoder-Black, Deanna (2017) "The ompC lementarity between Theoretical Linguistics, Neurolinguistics, and Communication Sciences and Disorders," Linguistic Portfolios: Vol. 6 , Article 2. Available at: https://repository.stcloudstate.edu/stcloud_ling/vol6/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by theRepository at St. Cloud State. It has been accepted for inclusion in Linguistic Portfolios by an authorized editor of theRepository at St. Cloud State. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The ompleC mentarity between Theoretical Linguistics, Neurolinguistics, and Communication Sciences and Disorders Cover Page Footnote This paper was presented as the keynote address to the Minnesota Undergraduate Linguistics Symposium, held at St. Cloud State University, St. Cloud, MN, in April 2016. This article is available in Linguistic Portfolios: https://repository.stcloudstate.edu/stcloud_ling/vol6/iss1/2 Yoder-Black: The Complementarity between Theoretical Linguistics, Neurolinguis Linguistic Portfolios–ISSN 2472-5102 –Volume 6, 2017 | 2 THE COMPLEMENTARITY BETWEEN THEORETICAL LINGUISTICS, NEUROLINGUISTICS, AND COMMUNICATION SCIENCES AND DISORDERS DEANNA YODER-BLACK MS, CCC-SLP/L ABSTRACT As science evolves, there is an ever-increasing interplay between disciplines. In Communication Sciences and Disorders interdisciplinary theory is needed because of a number of factors such as the growing detail in imaging technology, the development of new strategies in the identification and the treatment of disease, and the nuances that arise in fields that have become more and more specialized. -

Indexicals As Weak Descriptors

Indexicals as Weak Descriptors Andy Lücking Goethe University Frankfurt Abstract Indexicals have a couple of uses that are in conflict with the traditional view that they directly refer to indices in the utterance situation. But how do they refer instead? It is argued that indexicals have both an indexical and a descriptive aspect – why they are called weak descriptors here. The indexical aspect anchors them in the actual situation of utterance, the weak descriptive aspect sin- gles out the referent. Descriptive uses of “today” are then attributed to calendric coercion which is triggered by qunatificational elements. This account provides a grammatically motivated formal link to descriptive uses. With regard to some uses of “I”, a tentative contiguity rule is proposed as the reference rule for the first person pronoun, which is oriented along recent hearer-oriented accounts in philosophy, but finally has to be criticized. 1 Descriptive Indexicals Indexicals have descriptive uses as exemplified in (1a) (taken from Nunberg, 2004, p. 265): (1) a. Today is always the biggest party day of the year. b. *November 1, 2000 is always the biggest party day of the year. According to Nunberg (2004), today in (1a) is interpreted as picking out a day type or day property instead of referring to a concrete day, since “[. ] the interpretations of these uses of indexicals are the very things that their linguistic meanings pick out of the context.” (p. 272). The full date in (1b), to the contrary, refers to a particular day and has no such type or property reading. The interpretations of both sentences in (1) diverge, even if both sentences are produced on November 1, 2000.