The Lasallian Understanding of Gratuity.” AXIS: Journal of Lasallian Higher Education 8, No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rule and Foundational Documents

Rule and Foundational Documents Frontispiece: facsimile reproduction of a page—chapter 22, “Rules Concern- ing the Good Order and Management of the Institute”—from the Rule of the Brothers of the Christian Schools, the 1718 manuscript preserved in the Rome archives of the Institute. Photo E. Rousset (Jean-Baptiste de La Salle; Icono- graphie, Boulogne: Limet, 1979, plate 52). Rule and Foundational Documents John Baptist de La Salle Translated and edited by Augustine Loes, FSC, and Ronald Isetti Lasallian Publications Christian Brothers Conference Landover, Maryland Lasallian Publications Sponsored by the Regional Conference of Christian Brothers of the United States and Toronto Editorial Board Luke Salm, FSC, Chairman Paul Grass, FSC, Executive Director Daniel Burke, FSC William Mann, FSC Miguel Campos, FSC Donald C. Mouton, FSC Ronald Isetti Joseph Schmidt, FSC Augustine Loes, FSC From the French manuscripts, Pratique du Règlement journalier, Règles communes des Frères des Écoles chrétiennes, Règle du Frère Directeur d’une Maison de l’Institut d’après les manuscrits de 1705, 1713, 1718, et l’édition princeps de 1726 (Cahiers lasalliens 25; Rome: Maison Saint Jean-Baptiste de La Salle, 1966); Mémoire sur l’Habit (Cahiers lasalliens 11, 349–54; Rome: Maison Saint Jean-Baptiste de La Salle, 1962); Règles que je me suis imposées (Cahiers lasalliens 10, 114–16; Rome: Maison Saint Jean-Baptiste de La Salle, 1979). Rule and Foundational Documents is volume 7 of Lasallian Sources: The Complete Works of John Baptist de La Salle Copyright © 2002 by Christian Brothers Conference All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Control Number: 2002101169 ISBN 0-944808-25-5 (cloth) ISBN 0-944808-26-3 (paper) Cover: Portrait of M. -

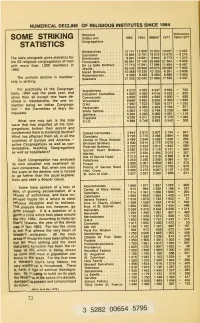

Some Striking

NUMERICAL DECLINE OF RELIGIOUS INSTITUTES SINCE 1964 Religious Difference SOME STRIKING Orders and 1964/1977 STATISTICS Congregations Benedictines 12 131 12 500 12 070 10 037 -2 463 Capuchins 15 849 15 751 15 575 12 475 - 3 276 - The table alongside gives statistics for Dominicans 9 991 10091 9 946 8 773 1 318 the 62 religious congregations of men Franciscans 26 961 27 140 26 666 21 504 -5 636 17584 11 484 - 6 497 . 17 981 with more than 1,000 members in De La Salle Brothers . 17710 - Jesuits 35 438 35 968 35 573 28 038 7 930 1962. - Marist Brothers 10 068 10 230 10 125 6 291 3 939 Redemptorists 9 308 9 450 9 080 6 888 - 2 562 uniform decline in member- - The Salesians 21 355 22 042 21 900 17 535 4 507 ship is striking. practically all the Congrega- For Augustinians 4 273 4 353 4 447 3 650 703 1964 was the peak year, and 3 425 625 tions, . 4 050 Discalced Carmelites . 4 050 4016 since then all except one have de- Conventuals 4 650 4 650 4 590 4000 650 4 333 1 659 clined in membership, the one ex- Vincentians 5 966 5 992 5 900 7 623 7 526 6 271 1 352 ception being an Indian Congrega- O.M.I 7 592 Passionists 3 935 4 065 4 204 3 194 871 tion - the Carmelites of Mary Im- White Fathers 4 083 4 120 3 749 3 235 885 maculate. Spiritans 5 200 5 200 5 060 4 081 1 119 Trappists 4 339 4 211 3819 3 179 1 032 What, one may ask, is this tidal S.V.D 5 588 5 746 5 693 5 243 503 wave that has engulfed all the Con- gregations, broken their ascent and condemned them to statistical decline? Calced Carmelites ... -

Superiors General 1952-1988 Brothers Josaphat 1952-1964 Iii

BROTHERS JOSAPHAT 1952-1964 I II SUPERIORS GENERAL 1952-1988 BROTHERS JOSAPHAT 1952-1964 III BROTHERS OF THE SACRED HEART SUPERIORS GENERAL 1952-1988 Br. Bernard Couvillion, S.C. ROME 2015 IV SUPERIORS GENERAL 1952-1988 BROTHERS JOSAPHAT 1952-1964 V INTRODUCTION With great joy I present to all the partners in our mission – brothers, laypeople, and others – the history of our Superiors Gen- eral during the period from 1952 to 1988: Brothers Josaphat (Joseph Vanier), Jules (Gaston Ledoux), Maurice Ratté and Jean- Charles Daigneault. This history is meant as a remembrance, a grateful recognition, and an encouragement. In the first place, it is meant as a remem- brance, profoundly rooted in our spirit and in our heart, full of es- teem toward each one of them. We remember them especially for their human and spiritual greatness and their closeness to God. We recall their remarkable service of authority in the animation of their brothers and in the revitalization of the prophetic mission of our In- stitute on behalf of young people, particularly those most in need. Calling to mind the lives and the works of our brothers, we thank the God of all goodness for the magnificent gifts which he placed in each of them. In doing so, we recognize the evangelical wisdom of our protagonists, who throughout their life knew how to multiply the talents they had received. Our brothers experienced the joy of feeling loved by God. He wanted them to know the depth of his divine love toward all hu- manity and toward each one of them personally. -

Lasallian Identity According to the Brothers' Formulas of Profession

“T O PROCURE YOUR GLORY ” LASALLIAN IDENTITY ACCORDING TO THE BROTHERS ’ FORMULAS OF PROFESSION 1 MEL BULLETIN N. 54 - December 2019 Institute of the Brothers of the Christian Schools Secretariat for Association and Mission Editor: Br. Nestor Anaya, FSC [email protected] Editorial Coordinators: Mrs. Ilaria Iadeluca - Br. Alexánder González, FSC [email protected] Graphic Layout: Mr. Luigi Cerchi [email protected] Service of Communications and Technology Generalate, Rome, Italy 2 MEL BULLETINS 54 “T O PROCURE YOUR GLORY ” LASALLIAN IDENTITY ACCORDING TO THE BROTHERS ’ FORMULAS OF PROFESSION BROTHER JOSEAN VILLALABEITIA , FSC 3 INTRODUCTION 4 The Brothers of the Christian Schools, founded by Saint John Baptist de La Salle in 1679, have used different formulas throughout their history to affirm their religious profession. Although the basic structure of them all has faithfully respected the outline proposed by the Founder and the first Brothers in the foundation’s early years (1691-1694), it is no less true that the content included in this permanent context has varied substantially over the years. The most recent change was made, precisely, by the Institute’s penultimate General Chapter in the Spring of 2007. A profession formula is not just any text, at least among Lasallians. Since the beginning, all the essentials of Lasallian consecration, what De La Salle’s followers are and should be, are contained therein: God, other Lasallians (i.e., the community), the school, the poor, the radical nature of its presentation. It is therefore an essential part of our institutional heritage, on which it would be advisable to return more often than we usually do. -

Jean-Baptiste De La Salle from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Jean-Baptiste de La Salle From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Saint John Baptist de La Salle Official portrait of St. John Baptist de La Salle by Pierre Leger (date unknown) Priest and founder Born 30 April 1651 Reims, Champagne, Kingdom of France Died 7 April 1719 (aged 67) Saint-Yon, Normandy, Kingdom of France Honored in Roman Catholic Church Beatified February 19, 1888 Canonized May 24, 1900, by Pope Leo XIII Majorshrine Sanctuary of John Baptist de La Salle, Casa Generalizia, Rome, Italy Feast Church: April 7 May 15 (General Roman Calendar1904-1969, and Lasallian institutions) Attributes stretched right arm with finger pointing up, instructing two children standing near him, books Patronage Teachers of Youth, (May 15, 1950, Pius XII), Institute of the Brothers of the Christian Schools, Lasallian educational institutions, educators, school principals, teachers John Baptist de La Salle (30 April 1651 – 7 April 1719) was a French priest, educational reformer, and founder of the Institute of the Brothers of the Christian Schools. He is a saint of the Roman Catholic church and the patron saint of teachers. De La Salle dedicated much of his life to the education of poor children in France; in doing so, he started many lasting educational practices. He is considered the founder of the first Catholic schools. Contents [hide] 1 Life and work 2 Sisters of the Child Jesus 3 Institute of the Brothers of the Christian Schools 4 Veneration 5 Legacy 6 See also 7 References 8 Further reading 9 External links Life and work[edit] De La Salle was born to a wealthy family in Reims, France on April 30, 1651.[1] He was the eldest child of Louis de La Salle and Nicolle de Moet de Brouillet. -

The Lasallian Tradition and Its Broad Possibilities.” AXIS: Journal of Lasallian Higher Education 6, No

Schweigl, Paul. “The Lasallian Tradition and Its Broad Possibilities.” AXIS: Journal of Lasallian Higher Education 6, no. 3 (Institute for Lasallian Studies at Saint Mary’s University of Minnesota: 2015). © Paul Schweigl. Readers of this article have the copyright owner’s permission to reproduce it for educational, not-for-profit purposes, if the author and publisher are acknowledged in the copy. The Lasallian Tradition and Its Broad Possibilities Paul Schweigl, La Salle University, Philadelphia, PA, USA Introduction In 1990, the promulgation of apostolic constitution Ex Corde Ecclesiae by Pope John Paul II intensified discussion over the mission and identity of Catholic institutions of higher learning. Particularly in the United States, where a disproportionately large percentage of such institutions are located, the document and its subsequent implementation by the American bishops were watched with a combination of hopefulness and suspicion. On the one hand, Ex Corde’s assertions that “by its Catholic character, a University is made more capable of conducting an impartial search for truth…that is neither subordinated to nor conditioned by particular interests of any kind” seemed to dovetail nicely with the cherished American academic values of academic freedom and institutional autonomy.2 On the other hand, the document’s mention of the Canon Law requirement that “those who teach theological disciplines in any institute of higher studies have a mandate from the competent ecclesiastical authority”3 seemed a blatant grab for control of classroom content by the hierarchy. The legitimate concerns raised by Ex Corde were mitigated by the productive relationship- building that took place between bishops and university4 administrators in the wake of Ex Corde’s promulgation. -

Myanmar Catholic Church Found in Historical Records (1287-1900)

MYANMAR CATHOLIC CHURCH FOUND IN HISTORICAL RECORDS (1287-1900) The most ancient sign of Christianity in Myanmar can be found on the mural painting of Roman and Greek crosses inside Kyansittha cave in Bagan which had been established during the time of Bagan Dynasty (9-13 AD). Nestorians were among the Mongol soldiers who had marched into Bagan in 1287 AD. Basing on this mural it can be said that Christians had set foot on Myanmar soil ever since the end of 13th century. King Min Bin from Rakhine had employed Portuguese soldiers and erected Myuk U or Myo Haung fortress. There were Portuguese mercenary soldiers under the King Tabinshwehtee. They were being accompanied by some Jesuits for their spiritual assistance. Philip de Brito, a Portuguese, reached Rakhine in 1599 and served the King Minrazagyi. He had been delegated by the King to occupy Than Hlyin with guards. He did not fail to offer annual tribute to the Kings of Rakhine and Taungngu. He built a church at Than Hlyin for his conferrers and raised Catholicism. The priests were the Jesuits. In 1613, King Mahadamaraza conquered Than Hlyin, executed de Brito and deported the prisoners of war to Ava. The Catholic prisoners and their descendents were known as “Bayingyi”. In 1721, Fr. Sigis Mondo Calchi, a Barnabite together with Fr. Giuseppe Vittoni arrived from Italy and began their mission in Pegu and Ava. King Taninganwe of Ava, in 1723, invited Fr. S. Calchi to his imperial city, Ava. Fr. S. Calchi’s report, after the audience with the king, to his Superior General in Italy reads; 1 After giving permission to build churches and to preach the Word of God, His Majesty had helped us with donations to build the church. -

Dear Lasallians

ISSUE 17 MONTHLY NEWSLETTER March/April 2017 Lasallians Without Limits, working for a hopeful future. Dear Lasallians, During the month of November, Brothers Lewis and Shashi spent a month of preparation for their Perpetual Profession in a Carmelite Monastery in New South Wales, Australia. During that time they reflected upon the fact that Perpetual Profession is not measured in terms of time but that it is an occasion when one gives oneself to God absolutely, today, forever in time and beyond time into eternity. The Brothers expressed a desire to be united for all time and beyond all time. They desired to be united with their God uninterruptedly for this moment unto eternity as De La Salle Brothers. By their Perpetual Profession they stated their commitment to unite themselves and remain in society for their whole lives with the Brothers as articulated in the Formula in Miguel House for Aspirants, Caritas New Zealand, the mission would not be viable. We must not forget of Vows they professed at ceremonies in December Lasallian Mission Services and international service those Brothers on whose shoulders we stand who in Faisalabad, Pakistan and in February at Mangere in the Generalate. are now in retirement or have gone to their eternal East, New Zealand. reward. Their constant prayer for the mission is And there are the Brothers who serve on the District valued and appreciated. The religious profession of Brothers Shashi and Council, Lasallian Mission Council, Sector Councils, Lewis gives a clear indication that the form of District Commissions, Economic Council, Boards of Congratulations to Brothers Shashi and Lewis. -

Church Community and Ministries RCIA Slide Presentation 12

Sacraments of Vocation The Community, its Life and Ministry Joe Barr and Michael Fallon 1 Christian Belief Christian Living www.mbfallon.com Church Creation Audio CD’s Homilies Articles Education Fundamentalism Welcome to my site God Islam Jesus Index of Topics Liturgy Mission MSC Click on “RCIA” (left menu) New Testament Old Testament Pope Francis n. 12. Community & Ministries Prayer Priesthood Religious Life RCIA/Cursillo. VOCATION (vocare – to call) 1. God calls each person to ‘live and to live to the full’(John 10:10). 2. God offers each person all the grace needed to do this, but God respects our freedom to accept or to reject grace. 3. Each person’s vocation is unique, and is related to gifts, opportunities, environment, education, and experiences. 4. The call is never withdrawn, and we can only start out afresh from where we now are. 3 There are varieties of gifts, but the same Spirit; and there are varieties of ministries, but the same Lord; and there are varieties of ways of energising, but it is the same God who activates all of them in everyone. To each is given the manifestation of the Spirit for the common good’(1Cor 12:4-7). CAREER or VOCATION ? Something we ‘do’ – a Something that influences job. It can be changed our whole life. It without really affects the way we look affecting our identity. at the world and the It is temporary – things we do. It alters however long term – our attitude to love and and will end, leaving affects our relationship us as the same person. -

Lasallian Summer 09 Edition

LTahe sallian Great Britain and Malta Issue 1, Summer / Autumn 2009 for people inspired by St John Baptist De La Salle Pupil Listening Out ....? Service see page 20 page 29 Br Benet RIP Kintbury Volunteers LDWP Volunteers Education at RTU page 6 page 12 page 22 page 26 Contents Front Cover 3. A Word from Brother Aidan 4. News page 6 Brother Benet Conroy, 1943 - 2009 by Br Owen Smith 8. John Baptist De La Salle - inspires many educators today by Br Nick Hutchinson 10. Being a Lasallian Educator De La Salle School, St. Helens What it means to Gery Short, San Francisco - see page 29 12. The Kintbury Volunteers 2008 / 2009 The nine volunteers reflect on their time at Kintbury Poster 14 Signum Fidei Association, Malta 16. “Teachers called to be visible angels” says De La Salle Br Nick Hutchinson reflects on these words “Take even more care of the young people entrusted to you 18. Getting to Know .... Interviews with two headteachers than if they were Frank Micallef (Stella Maris) and Brendan Wall (St. Augustine’s) the children of a king.” Photograph by Claire Arni 20. De La Salle Humanities College, Liverpool - see article on Education at RTU, India, page 26. 22. Lasallian Developing World Projects by Br John Deeney Each issue of Lasallians will contain a poster . 25. Brother Austin raises £30,000 26. Lessons in Love - Education at RTU in India by Oriole Henry Next Issue 28. Coatbridge, Our Most Northerly Community Please send all contributions for by Br Livinus the Winter / Spring issue to 29. -

The Experience of Lasallian Association on the Part of Lay “Associates in Fact” in the District of San Francisco Gregory T

The University of San Francisco USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center Doctoral Dissertations Theses, Dissertations, Capstones and Projects 2012 The Experience of Lasallian Association on the Part of Lay “Associates in Fact” in the District of San Francisco Gregory T. Kopra [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.usfca.edu/diss Part of the Education Commons Recommended Citation Kopra, Gregory T., "The Experience of Lasallian Association on the Part of Lay “Associates in Fact” in the District of San Francisco" (2012). Doctoral Dissertations. 26. https://repository.usfca.edu/diss/26 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, Capstones and Projects at USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The University of San Francisco THE EXPERIENCE OF LASALLIAN ASSOCIATION ON THE PART OF LAY “ASSOCIATES IN FACT” IN THE DISTRICT OF SAN FRANCISCO A Dissertation Presented to The Faculty of the School of Education Department of Leadership Studies Catholic Educational Leadership Program In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Education by Gregory T. Kopra San Francisco May 2012 THE UNIVERSITY OF SAN FRANCISCO Dissertation Abstract The Experience of Lasallian Association on the Part of Lay “Associates in Fact” in the District of San Francisco The staffs of Catholic schools have undergone a wholesale change in the past 50 years. -

Religious Community Facts

RELIGIOUS COMMUNITY FACTS DID YOU KNOW? For over 25 years, the Franciscan Sisters of the Sacred Heart held their annual garage sale with proceeds to their mission activity in Brazil, moving reusable trash to renewable treasures. The Institute of the Blessed Virgin Mary was founded in Belgium in 1609 by a young Englishwoman named Mary Ward, was suppressed in 1631, yet continued to quietly grow through its educational endeavors throughout Europe, finally receiving full approval in 1877. The Mantellate Sisters Servants of Mary were founded in 1891 in Treppio, Italy (near Pistoia). This Year of Consecrated Life, 2015, is the 150th anniversary of the founding of the Sisters of St. Francis of Mary Immaculate in Joliet, also referred to as the Joliet Franciscans. They were the first group of Franciscan sisters incorporated in the State of Illinois, which was in 1874. 125 years ago, the Servants of the Holy Heart of Mary came to Bourbonnais from Paris, to minister in the infirmary at St. Viator’s College and within ten years founded a hospital and boarding school. During the years of 1885 to 1900, Chicago became an important Czech Center for the Benedictine Sisters. The founders of St. Procopius Abbey and Sacred Heart Monastery, following the model of Saints Benedict and Scholastica, were brother and Sister. Both Abbot Nepomuk Jaeger and Mother Nepomuk Jaeger had a famous Czech saint, John Nepomucene, as their patron. The masterpiece poem by Jesuit Gerard Manley Hopkins titled “The Wreck of Deutschland” was dedicated to five Franciscan Sisters, Daughters of the Sacred Hearts of Jesus and Mary, who left their Motherhouse in Salzkotten, Germany to join 19 of their Sisters (later known as Wheaton Franciscans).