Whitewashing WWII Sexual Memory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The History/Literature Problem in First World War Studies Nicholas Milne-Walasek Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Graduate

The History/Literature Problem in First World War Studies Nicholas Milne-Walasek Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a doctoral degree in English Literature Department of English Faculty of Arts University of Ottawa © Nicholas Milne-Walasek, Ottawa, Canada, 2016 ii ABSTRACT In a cultural context, the First World War has come to occupy an unusual existential point half- way between history and art. Modris Eksteins has described it as being “more a matter of art than of history;” Samuel Hynes calls it “a gap in history;” Paul Fussell has exclaimed “Oh what a literary war!” and placed it outside of the bounds of conventional history. The primary artistic mode through which the war continues to be encountered and remembered is that of literature—and yet the war is also a fact of history, an event, a happening. Because of this complex and often confounding mixture of history and literature, the joint roles of historiography and literary scholarship in understanding both the war and the literature it occasioned demand to be acknowledged. Novels, poems, and memoirs may be understood as engagements with and accounts of history as much as they may be understood as literary artifacts; the war and its culture have in turn generated an idiosyncratic poetics. It has conventionally been argued that the dawn of the war's modern literary scholarship and historiography can be traced back to the late 1960s and early 1970s—a period which the cultural historian Jay Winter has described as the “Vietnam Generation” of scholarship. -

Nielsen Collection Holdings Western Illinois University Libraries

Nielsen Collection Holdings Western Illinois University Libraries Call Number Author Title Item Enum Copy # Publisher Date of Publication BS2625 .F6 1920 Acts of the Apostles / edited by F.J. Foakes v.1 1 Macmillan and Co., 1920-1933. Jackson and Kirsopp Lake. BS2625 .F6 1920 Acts of the Apostles / edited by F.J. Foakes v.2 1 Macmillan and Co., 1920-1933. Jackson and Kirsopp Lake. BS2625 .F6 1920 Acts of the Apostles / edited by F.J. Foakes v.3 1 Macmillan and Co., 1920-1933. Jackson and Kirsopp Lake. BS2625 .F6 1920 Acts of the Apostles / edited by F.J. Foakes v.4 1 Macmillan and Co., 1920-1933. Jackson and Kirsopp Lake. BS2625 .F6 1920 Acts of the Apostles / edited by F.J. Foakes v.5 1 Macmillan and Co., 1920-1933. Jackson and Kirsopp Lake. PG3356 .A55 1987 Alexander Pushkin / edited and with an 1 Chelsea House 1987. introduction by Harold Bloom. Publishers, LA227.4 .A44 1998 American academic culture in transformation : 1 Princeton University 1998, c1997. fifty years, four disciplines / edited with an Press, introduction by Thomas Bender and Carl E. Schorske ; foreword by Stephen R. Graubard. PC2689 .A45 1984 American Express international traveler's 1 Simon and Schuster, c1984. pocket French dictionary and phrase book. REF. PE1628 .A623 American Heritage dictionary of the English 1 Houghton Mifflin, c2000. 2000 language. REF. PE1628 .A623 American Heritage dictionary of the English 2 Houghton Mifflin, c2000. 2000 language. DS155 .A599 1995 Anatolia : cauldron of cultures / by the editors 1 Time-Life Books, c1995. of Time-Life Books. BS440 .A54 1992 Anchor Bible dictionary / David Noel v.1 1 Doubleday, c1992. -

Hemingway: Works and Days

English Language and Literature Studies; Vol. 3, No. 1; 2013 ISSN 1925-4768 E-ISSN 1925-4776 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education Hemingway: Works and Days Shahla Sorkhabi Darzikola1 1 Department of English, Payame Noor University, Iran Correspondence: Shahla Sorkhabi Darzikola, Payame Noor University, Firozkooh, Tehran, Iran. Tel: 98-912-238-4192. E-mail: [email protected] Received: December 9, 2012 Accepted: January 11, 2013 Online Published: January 29, 2013 doi:10.5539/ells.v3n1p77 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/ells.v3n1p77 Abstract Considering Hemingway’s life and activities in different period of his life is one of the important legal issues that have gained particular significance of the reflection on his life on his works. So the later years of Hemingway’s life (1948-1962) are examined. The important fact that Hemingway was included in American Literature collected works cannot be overvalued. His style and theme issue are both conventional and classic of American text and he broke different fictional ground when he started printing his short stories. This article tries to delve more deeply how Hemingway's life impacted on his works. Keywords: existentialism, identity, nihilist, struggle, human belief, responsibility 1. Introduction Twentieth century has been at the mercy of various events which have been illustrated by intellectuals in different fields. Ernest Hemingway, the illustrious novelist has dealt with the question of existence in his works. In this article among the many characteristics revealing existence, the major ones including the themes of identity and existence have been analyzed with regard to the techniques of the writer in his major works. -

With the Old Breed: at Peleliu and Okinawa PDF Book

WITH THE OLD BREED: AT PELELIU AND OKINAWA PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Professor of Biology E B Sledge | 384 pages | 05 Sep 2011 | Random House Publishing Group | 9780891419198 | English | New York, United Kingdom With the Old Breed: At Peleliu and Okinawa PDF Book Jocko Podcast Boo There were funny moments as well—the men reminding their green lieutenant of his earlier pledge to charge the Japanese with his knife and pistol and turn the tide of war all by himself, as said lieutenant is frantically digging a really deep foxhole after his first taste of combat. Eugene Sledge's book didn't lessen my love for that time period, nor my awe and gratitude for the men who served Another loss for my reading enjoyment is they also have such a close order view of what is going on, that you loose any big picture overview. But what really sets this apart are the author's honest descriptions of how he felt and his motivations in combat - comradeship, bravery, anger, You've read the other reviews, so you already know how good this is. Aug 16, Kate rated it it was amazing Shelves: war , history , wwii. His story was later central to Ken Burns' series, "The War. So all the armchair generals who think we messed up by dropping the A-Bomb need to read this book and remember that it took more than 80 days and over , dead Japanese to get a six mile island named Okinawa. Use your imagination, but add "hungry, tired, exhausted to the limits of your endurance, need to shit and there is no toilet or TP or privacy or even a trench anywhere and several thousand men are all crowded together in the same situation and also you're under heavy shelling and your buddies are getting blown to bits right and left. -

“Lest We Forget”: Canadian Combatant Narratives of the Great War by Monique Dumontet a Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of G

“Lest We Forget”: Canadian Combatant Narratives of the Great War by Monique Dumontet A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies of The University of Manitoba In partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of English, Film, and Theatre University of Manitoba Winnipeg, Manitoaba Copyright © 2010 by Monique Dumontet Library and Archives Bibliothèque et Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de l’édition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-70307-6 Our file Notre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-70307-6 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non- L’auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant à la Bibliothèque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par télécommunication ou par l’Internet, prêter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des thèses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, à des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non- support microforme, papier, électronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L’auteur conserve la propriété du droit d’auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protège cette thèse. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la thèse ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent être imprimés ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Paul Fussell, "Thank God for Atom the Bomb" in Thank God for the Atom Bomb and Other Essays (New York: Summit Books, 1988)

Paul Fussell, "Thank God For Atom The Bomb" in Thank God for the Atom Bomb and Other Essays (New York: Summit Books, 1988). First published as "Hiroshima: A Soldier's View," New Republic (August 1981) (Page 13) Many years ago in New York I saw on the side of a bus a whiskey ad I've remembered all this time. It's been for me a model of the short poem, and indeed I've come upon few short poems subsequently that exhibited more poetic talent. The ad consisted of two eleven-syllable lines of "verse," thus: In life, experience is the great teacher. In Scotch, Teacher's is the great experience. (Page 14) For present purposes we must jettison the second line (licking our lips, to be sure, as it disappears), leaving the first to register a principle whose banality suggests that it enshrines a most useful truth. I bring up the matter because, writing on the forty-second anniversary of the atom-bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, I want to consider something suggested by the long debate about the ethics, if any, of that ghastly affair. Namely, the importance of experience, sheer, vulgar experience, in influencing, if not determining, one's views about that use of the atom bomb. The experience I'm talking about is having to come to grips, face to face, with an enemy who designs your death. The experience is common to those in the marines and the infantry and even the line navy, to those, in short, who fought the Second World War mindful always that their mission was, as they were repeatedly assured, "to close with the enemy and destroy him." Destroy, notice: not hurt, frighten, drive away, or capture. -

Thank God for the Atom Bomb?

THANK GOD FOR THE ATOM BOMB? By Richard Rice Images in the above collage: Background image of the Hiroshima Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall after the blast (National Archives). Left: 1926 photo of Emperor Hirohito (Library of Congress). Right: Churchill, Truman, and Stalin at the Potsdam Conference (Imperial War Museum, London, England). Photomontage created by Willa Davis. once received a call from the concerned editor of This minor incident is indicative of a much wider reluctance among many in the academic and teaching community to consider an education journal: “Could you find a source all historical aspects of a morally difficult topic. The horror of the bomb, both real and in our conscience, has led to a debate that con- Iother than Thank God for the Atom Bomb? We feel tinues today. As teachers who want to foster critical thinking skills in our students, we must expose them to facts and interpretations that it inappropriate for teachers to see it in a journal dedi- may not be politically correct. It is easy to condemn a weapon of mass destruction, but more difficult to understand why Truman and cated to international understanding.” Since the essay his inner circle made the decision to use it. Understanding both sides on travel versus tourism that I wanted to cite of the debate is critical to developing a more nuanced understanding of the bomb decision. appeared only in this provocatively titled collection of Within the limits of this brief essay I will cite arguments against the bomb more fully articulated elsewhere in this issue, and place Paul Fussell essays, they finally did allow it to appear Truman’s decision in the historical context of a bitter war. -

Literature for Composition Reading and Writing Arguments About Essays, Stories, Poems, and Plays

BARN.2138.bkfm.i-xxvi_BARN.2138.bkfm.i-xxvi 2/27/13 1:27 PM Page i INSTRUCTOR’S HANDBOOK TO ACCOMPANY Literature for Composition Reading and Writing Arguments About Essays, Stories, Poems, and Plays TENTH EDITION Edited by Sylvan Barnet Tufts University William Burto University of Massachusetts at Lowell William E. Cain Wellesley College Boston Columbus Indianapolis New York San Francisco Upper Saddle River Amsterdam Cape Town Dubai London Madrid Milan Munich Paris Montreal Toronto Delhi Mexico City São Paulo Sydney Hong Kong Seoul Singapore Taipei Tokyo BARN.2138.bkfm.i-xxvi_BARN.2138.bkfm.i-xxvi 2/27/13 1:27 PM Page ii Vice President and Editor in Chief: Joseph P. Terry Senior Supplements Editor: Donna Campion Electronic Page Makeup: Grapevine Publishing Services, Inc. Instructor’s Handbook to Accompany Literature for Composition: Essays, Stories, Poems, and Plays, Tenth Edition, by Sylvan Barnet, William Burto, and William E. Cain. Copyright © 2014, 2011, 2007 Pearson Education, Inc. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. Instructors may re- produce portions of this book for classroom use only. All other reproductions are strictly prohibited without prior permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10–online–15 14 13 12 ISBN 10: 0-321-84213-8 www.pearsonhighered.com ISBN 13: 978-0-321-84213-8 BARN.2138.bkfm.i-xxvi_BARN.2138.bkfm.i-xxvi 2/27/13 1:27 PM Page iii Contents Preface xv Using the “Short Views” and the “Overviews” xvii Guide to MyLiteratureLabTM xix The First Day 1 PART I Getting Started: From Response to Argument CHAPTER 1 How to Write an Effective Essay: A Crash Course 4 CHAPTER 2 The Writer as Reader 5 KATE CHOPIN Ripe Figs 5 LYDIA DAVIS City People 6 RAY BRADBURY August 2026: There Will Come Soft Rains 7 MICHELE SERROS Senior Picture Day 8 GUY DE MAUPASSANT The Necklace 9 GUY DE MAUPASSANT Hautot and Son 13 T. -

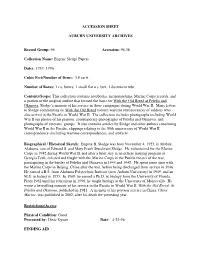

Accession Sheet

ACCESSION SHEET AUBURN UNIVERSITY ARCHIVES Record Group: 96 Accession: 96-38 Collection Name: Eugene Sledge Papers Dates: 1937- 1996 Cubic Feet/Number of Items:. 3.8 cu ft. Number of Boxes: 3 r.c. boxes, 1 small flat o.s. box, 1 document tube Contents/Scope: This collection contains notebooks, memorandums, Marine Corps records, and a portion of the original outline that formed the basis for With the Old Breed at Peleliu and Okinawa, Sledge’s memoir of his service in those campaigns during World War II. Many letters to Sledge commenting on With the Old Breed contain wartime reminiscences of soldiers who also served in the Pacific in World War II. The collection includes photographs including World War II era photos of his platoon, contemporary photographs of Peleliu and Okinawa, and photographs of veterans’ groups. It also contains articles by Sledge and other authors concerning World War II in the Pacific, clippings relating to the 50th anniversary of World War II, correspondence (including wartime correspondence), and artifacts. Biographical / Historical Sketch: Eugene B. Sledge was born November 4, 1923, in Mobile, Alabama, son of Edward S. and Mary Frank Sturdivant Sledge. He volunteered for the Marine Corps in 1942 during World War II, and after a brief stay in an officer training program at Georgia Tech, enlisted and fought with the Marine Corps in the Pacific theater of the war, participating in the battles of Peleliu and Okinawa in 1944 and 1945. He spent some time with the Marine Corps in Beijing, China after the war, before being discharged from service in 1946. -

Not Even Past." William Faulkner NOT EVEN PAST

"The past is never dead. It's not even past." William Faulkner NOT EVEN PAST Search the site ... Read More About the First Like 1 World War Tweet What’s new and interesting on World War 1? In this Centennial year, you may want to read up on World War I. Here are a few suggestions from UT History faculty who have been studying and teaching about the First World War: David Crew, Philippa Levine, Mary Neuburger, Charters Wynn, and Emilio Zamora. Here are their suggestions. Richard Fogarty, Race and War in France: Colonial Subjects in the French Army, 1914- 1918 How did the half million soldiers who were drafted from France’s colonies fare during the war? Margaret MacMillan, The War That Ended Peace: The Road to 1914 In a lively style, The War That Ended Peace portrays the military leaders, politicians, diplomats, bankers, and the extended, interrelated family of crowned heads across Europe who failed to stop the descent into war Louise Miller, A Fine Brother: The Life of Captain Flora Sandes A readable and informative biography of a remarkable British woman who went to war- torn Serbia to minister to soldiers and typhus ridden civilians, but ended up entering the Serbian Army, where she rose to the level of decorated ocer. Karen Petrone, The Great War in Russian Memory (2011) The socialist revolution and civil war that followed WW1 in the Russian empire meant that the war was never publically commemorated there as it was in western Europe. But it wasn’t entirely forgotten and this book shows how the Russian war was remembered. -

Never Such Innocence Again

Humanities Never Such Innocence Again lier works include Samuel Johnson and the Life of Writing (wherefore his son’s name is Sam; a daughter I am saying that there seems to be one domi is Rosalind, “from Shakespeare”). His attachment to nating form of modern understanding; that it is essen England, and his own front-line memories of war— tially ironic; and that it originates largely in the appli “WW II”— beguiled him into the years of research that cation of mind and memory to the events of the Great are evident in his new book. A Humanities Endowment War— Paul Fussell fellowship freed him for the actual writing. The result, in the words of the late Lionel Trilling, is “an original In Victoria’s long reign (1837-1901) the British Empire and brilliant piece of cultural history and one of the multiplied fourfold through what Kipling hymned as most deeply moving books I have read in a long time.” “the savage wars of peace.” These were fought by a The Great War and Modern Memory draws on a relatively small army officered from the English gov hoard of English literary and historical materials. These erning class— a class serenely convinced of its su had of course been heavily mined already, suggesting periority to the “ lower orders” at home and, by exten the temerity of an outsider’s sifting them again. But sion, to lesser breeds abroad. Fussell (rhymes with tussle) dug out unsuspected The pleasure-loving Edward VII had put his stamp gems, working them into a mosaic of the broadest on the succeeding decade, providing, in his funeral, erudition. -

Paul Fussell: a Remembrance

Two Commentaries by W. D. Ehrhart Paul Fussell: A Remembrance ot surprisingly, virtually every publication in the English-speaking world from the New York Times and Britain’s The Guardian to the Scranton Times Tribune and the Kennebec Journal took note of the recentN death of Paul Fussell. Beginning with the 1975 publication of his landmark study The Great War and Modern Memory, which earned him both the National Book Award and the National Book Critics Circle Award, he rapidly became a towering figure on the cultural landscape of modern American life. One need only head for the computer and search for “Paul Fussell obituaries” to see the magnitude of his influence and to read about the particulars of his life from his privileged upbringing as the son of a prominent lawyer to his near-fatal wounding in Europe during World War II to his career as scholar, professor, and social critic. Most of the obituaries describe him as grouchy, curmudgeonly, caustic, or acerbic. He himself attributed his attitude to his experiences in the war, which left him permanently, in his own words, “a pissed-off infantryman.” My first encounter with Fussell—or, more accurately, with Fussell’s writing— came in the fall of 1970, during my second year of college, before he had become famous. I was taking a course with the poet Daniel Hoffman in which the assigned text was Fussell’s Poetic Meter and Poetic Form, a book which was then rapidly on its way to becoming for the writing of poetry what William Strunk and E.