Agrarian Purpose and Thoreau's Ecological Knowing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![HUMS 4904A Schedule Mondays 11:35 - 2:25 [Each Session Is in Two Halves: a and B]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6562/hums-4904a-schedule-mondays-11-35-2-25-each-session-is-in-two-halves-a-and-b-86562.webp)

HUMS 4904A Schedule Mondays 11:35 - 2:25 [Each Session Is in Two Halves: a and B]

CARLETON UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF THE HUMANITIES Humanities 4904 A (Winter 2011) Mahatma Gandhi Across Cultures Mondays 11:35-2:25 Prof. Noel Salmond Paterson Hall 2A46 Paterson Hall 2A38 520-2600 ext. 8162 [email protected] Office Hours: Tuesdays 2:00 - 4:00 (Or by appointment) This seminar is a critical examination of the life and thought of one of the pivotal and iconic figures of the twentieth century, Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi – better known as the Mahatma, the great soul. Gandhi is a bridge figure across cultures in that his thought and action were inspired by both Indian and Western traditions. And, of course, in that his influence has spread across the globe. He was shaped by his upbringing in Gujarat India and the influences of Hindu and Jain piety. He identified as a Sanatani Hindu. Yet he was also influenced by Western thought: the New Testament, Henry David Thoreau, John Ruskin, Count Leo Tolstoy. We will read these authors: Thoreau, On Civil Disobedience; Ruskin, Unto This Last; Tolstoy, A Letter to a Hindu and The Kingdom of God is Within You. We will read Gandhi’s autobiography, My Experiments with Truth, and a variety of texts from his Collected Works covering the social, political, and religious dimensions of his struggle for a free India and an India of social justice. We will read selections from his commentary on the Bhagavad Gita, the book that was his daily inspiration and that also, ironically, was the inspiration of his assassin. We will encounter Gandhi’s clash over communal politics and caste with another architect of modern India – Bimrao Ambedkar, author of the constitution, Buddhist convert, and leader of the “untouchable” community. -

(Quakers) in Britain Testimonies Including Index of Epistles

Yearly Meeting of the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers) in Britain Testimonies including index of epistles Compiled for Yearly Meeting 2020 Q Logo - Sky - CMYK - Black Text.pdf 1 26.04.2016 04.55 pm C M Y CM MY CY CMY K Credit: Mike Pinches for BYM Pinches for Mike Credit: This booklet is part of ‘Proceedings of the Yearly Meeting of the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers) in Britain 2019’, a set of publications published for Yearly Meeting. The full set comprises: 1. The Yearly Meeting programme, with introductory material for Yearly Meeting 2019 and annual reports of Meeting for Sufferings, Quaker Stewardship Committee and other related bodies 2. Testimonies 3. Minutes, to be distributed after the conclusion of Yearly Meeting 4. The formal Trustees’ annual report including financial statements for the year ended December 2019 5. Tabular statement. All documents are available online at www.quaker.org.uk/ym. If these do not meet your accessibility needs, or the needs of someone you know, please email [email protected]. Printed copies of all documents will be available at Yearly Meeting. All Quaker faith & practice references are to the online edition, which can be found at www.quaker.org.uk/qfp. Yearly Meeting of the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers) in Britain Testimonies Contents Epistles 5 Introduction 6 Warren Adams 8 Judith Mary Effer 9 Marion Fairweather 11 Sheila J. Gatiss 12 Joyce Gee 14 Joan Gibson 16 David Henshaw 17 Kate Joyce 20 Richard Lacock 23 Lesley Parker 25 Erika Margarethe Zintl Pearce 27 Angela Maureen Pivac 30 Margaret Rowan 32 Peter Rutter 34 Margaret Slee 36 Rachel Smith 38 Claire Watkins 39 Allan N. -

From Engineering Hydrology to Earth System Science: Milestones in the Transformation of Hydrologic Science

Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci., 22, 1665–1693, 2018 https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-22-1665-2018 © Author(s) 2018. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. From engineering hydrology to Earth system science: milestones in the transformation of hydrologic science Murugesu Sivapalan1,* 1Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, Department of Geography and Geographic Information Science, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Urbana, Illinois 61801, USA * Invited contribution by Murugesu Sivapalan, recipient of the EGU Alfred Wegener Medal & Honorary Membership 2017. Correspondence: Murugesu Sivapalan ([email protected]) Received: 13 November 2017 – Discussion started: 15 November 2017 Revised: 2 February 2018 – Accepted: 5 February 2018 – Published: 7 March 2018 Abstract. Hydrology has undergone almost transformative hydrology to Earth system science, drawn from the work of changes over the past 50 years. Huge strides have been made several students and colleagues of mine, and discuss their im- in the transition from early empirical approaches to rigorous plication for hydrologic observations, theory development, approaches based on the fluid mechanics of water movement and predictions. on and below the land surface. However, progress has been hampered by problems posed by the presence of heterogene- ity, including subsurface heterogeneity present at all scales. எப்ெபாள் யார்யாரவாய் ் க் ேகட்ம் The inability to measure or map the heterogeneity every- அப்ெபாள் ெமய் ப்ெபாள் காண் ப த where prevented the development of balance equations and In whatever matter and from whomever heard, associated closure relations at the scales of interest, and has Wisdom will witness its true meaning. -

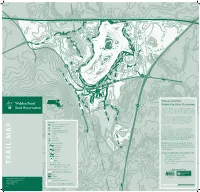

Walden Pond R O Oa W R D L Oreau’S O R Ty I a K N N U 226 O

TO MBTA FITCHBURG COMMUTER LINE ROUTE 495, ACTON h Fire d Sout Road North T 147 Fire Roa th Fir idge r Pa e e R a 167 Pond I R Pin i c o l Long Cove e ad F N Ice Fort Cove o or rt th Cove Roa Heywood’s Meadow d FIELD 187 l i Path ail Lo a w r Tr op r do e T a k e s h r F M E e t k a s a Heyw ’s E 187 i P 187 ood 206 r h d n a a w 167 o v o e T R n H e y t e v B 187 2 y n o a 167 w a 187 C y o h Little Cove t o R S r 167 d o o ’ H s F a e d m th M e loc Pa k 270 80 c e 100 I B a E e m a d 40 n W C Baker Bridge Road o EMERSON’S e Concord Road r o w s 60 F a n CLIFF i o e t c e R n l o 206 265 d r r o ’s 20 d t a o F d C Walden Pond R o oa w R d l oreau’s o r ty i a k n n u 226 o 246 Cove d C T d F Ol r o a O r i k l l d C 187 o h n h t THOREAU t c 187 a a HOUSE SITE o P P Wyman 167 r ORIGINAL d d 167 R l n e Meadow i o d ra P g . -

A New Look at Thoreau

ADDENDUM A NEW LOOK AT THOREAU In the summer of Thoreau did not put me to sleep. He shook me awake, 1984, as a college student hungry pointing me toward an alternative vision of the good life. to see the halls of power up close, I took a summer internship on Natural History, I saw just the thing to usher me blissfully into unconsciousness Capitol Hill. that night. Out of the corner of my eye, I’d spotted the bright green cover of It was heady Walden in the window of the museum bookshop. stuff for a 20-year-old. I shared a row Two years earlier, I’d been assigned to read Henry David Thoreau in American house with three other students a few Lit class and found him a colossal bore. His questioning of material gain left me blocks from the Capitol, passing the cold. I dreamed of a life after college that included more, not fewer, possessions. Library of Congress and Supreme I also wanted to be at the center of things, not sequestered in a shack by a pond. Court on my walk to work. Someone Walden seemed like a manual in how not to succeed. got me an insider tour of the White Finally, an author I’d endured in the classroom would have some use for me, his House, which allowed me to stick my prose as potent as a tranquilizer. I bought Walden from the Smithsonian and took head into the Oval Office and gaze it home, convinced that I carried literary laudanum in my hands. -

Agrarianism: an Ideology of the National FFA Organization

Journal of Agricultural Education Volume 54, Number 3, pp. 28 – 40 DOI: 10.5032/jae.2013.03028 Agrarianism: An Ideology of the National FFA Organization Michael J. Martin Colorado State University Tracy Kitchel University of Missouri The traditions of the National FFA Organization (FFA) are grounded in agrarianism. This ideology fo- cuses on the ability of farming and nature to develop citizens and integrity within people. Agrarianism has been an important thread of American rhetoric since the founding of country. The ideology has mor- phed over the last two centuries as the country developed from a nation of farmers to an industrial world power. The agrarian ideology that resonated in rural America during the formation of the FFA was southern agrarianism. Southern agrarian ideology argued for self-reliance and adherence to past tradi- tions. These concepts appear in the FFA traditions of the creed, opening ceremony, motto, and awards. The historical growth and success of the FFA within rural communities demonstrates the ability of the southern agrarian ideology to connect with contemporary rural values. However, the southern agrarian ideology may not connect with the culture of diverse, urban, or suburban students. Advisers of diverse, urban, or suburban FFA chapters may need to reconceptualize the FFA traditions to accommodate their students. Keywords: National FFA Organization; philosophy; ideology; agrarianism The theme Beyond Diversity to Cultural LaVergne, Larke, Elbert, & Jones, 2011). One Proficiency resonated at the 2011 American As- study highlighted how some non-FFA members sociation for Agricultural Education (AAAE) viewed FFA members as hicks (Phelps, Henry, conference. Fittingly, AAAE invited James & Bird, 2012). -

Gandhi: Sources and Influences. a Curriculum Guide. Fulbright-Hays Summer Seminars Abroad, 1997 (India)

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 421 419 SO 029 067 AUTHOR Ragan, Paul TITLE Gandhi: Sources and Influences. A CurriculumGuide. Fulbright-Hays SummerSeminars Abroad, SPONS AGENCY United States 1997 (India). Educational Foundationin India. PUB DATE 1997-00-00 NOTE 28p.; For other curriculum projectreports by 1997 seminar participants, see SO029 068-086. Seminar Her Ethos." title: "India and PUB TYPE Guides - Classroom EDRS PRICE - Teacher (052) MF01/PCO2 PlusPostage. DESCRIPTORS Asian Studies;Civil Disobedience; Culture; Ethnic Cultural Awareness; Groups; ForeignCountries; High Schools; *Indians; Instructional Materials;Interdisciplinary Approach; NonWestern Civilization; Social Studies;*World History; *WorldLiterature IDENTIFIERS Dalai Lama; *Gandhi (Mahatma); *India;King (Martin Luther Jr); Thoreau (HenryDavid) ABSTRACT This unit isintended for secondary literature, Asian students in American history, U.S. history,or a world cultures emphasis is placedon the literary class. Special David Thoreau, contributions of fourindividuals: Henry Mahatma Gandhi,Martin Luther King, The sections Jr., and the DalaiLama. appear in chronologicalorder and contain strategies that objectives and are designed tovary the materials the daily activities. students use in their Study questionsand suggested included. Background evaluation toolsare also is included inthe head notes of primary and secondary each section with sources listed in each is designed for section's bibliography.The unit four weeks, butcan be adapted to fit classroom needs. (EH) ******************************************************************************** -

Where I Lived, and What I Lived For

33171 97 1317-1322.ps 4/26/06 12:46 PM Page 1317 HENRY DAVID THOREAU [1817–1862] Where I Lived, and What I Lived For Henry David Thoreau was born in 1817 and raised in Concord, Massa- chusetts, living there for most of his life. Along with Ralph Waldo Emerson, Thoreau was one of the most important thinkers of his time in America and is still widely read today. Walden (1854), the work for which he is best known, is drawn from the journal he kept during his two-year-long stay in a cabin on Walden Pond. In Walden, Thoreau ex- plores his interests in naturalism, individualism, and self-sufficiency. He is also remembered for his essay “Civil Disobedience” (1849), an early, influential statement of this tactic of protest later practiced by Mahatma Gandhi and, under the leadership of Martin Luther King Jr., many in the civil rights movement. “Where I Lived, and What I Lived For” is taken from Walden. In it, Thoreau makes the argument for his going to live in the woods. Writing about Walden, scholars have pointed out that Thoreau was not particularly deep in the woods and that he was regularly visited and supplied with, among other things, pies. As you read, consider how this influences your acceptance of what he has to say. I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it had to teach, and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not lived. -

Quaker Language and Thought in Eighteenth- and Nineteenth-Century American Literature James Peacock Keele University, England

Quaker Studies Volume 12 | Issue 2 Article 4 2008 'What They Seek for is in Themselves': Quaker Language and Thought in Eighteenth- and Nineteenth-Century American Literature James Peacock Keele University, England Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/quakerstudies Part of the Christian Denominations and Sects Commons, and the History of Christianity Commons Recommended Citation Peacock, James (2008) "'What They eS ek for is in Themselves': Quaker Language and Thought in Eighteenth- and Nineteenth- Century American Literature," Quaker Studies: Vol. 12: Iss. 2, Article 4. Available at: http://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/quakerstudies/vol12/iss2/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ George Fox University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Quaker Studies by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ George Fox University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. QUAKER STUDIES 12/2 (2008) [196-215] ISSN 1363-013X 'WHAT THEY SEEK FOR IS IN THEMSELVES': QUAKER LANGUAGE AND THOUGHT IN EIGHTEENTH- AND NINETEENTH-CENTURY AMERICAN LITERATURE* James Peacock Keele University, Keele, England ABSTRACT This paper argues that Quakerism was an important influence on a number of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century American writers. Looking at the work of, amongst others, Charles Brockden Brown, Robert Montgomery Bird, Ralph Waldo Emerson and John Greenleaf Whittier, it demonstrates that both the stereotyped depiction of Quakers and the use of Quaker ideas, such as the inward light in literature of the period, helped writers tackle some of the paradoxes of democracy in a young nation. The perceived mystery of Quaker individualism is used in these texts first to dramatise anxiety over the formation ofAmerican 'character' as either fundamentally unique and unknowable or representative of the whole nation, and secondly for more constructive ends in order to create a language able to express unity in diversity. -

Within “Walden” by Henry David Thoreau and “The Death of An

Transcendentalism: Ethereal Experience or Tragic Naiveté? Within “Walden” by Henry David Thoreau and “The Death of an Innocent by Jon Krakauer, the individual’s search for isolation and a transcendental experience is illustrated with drastically different results. While both Thoreau and McCandless are indeed idealistic, Thoreau walked away from Walden Pond, McCandless did not. Your assignment is to analyze the similarities and differences of their transcendental experiences. Use: Thoreau’s “Walden” on page 205 of your texts. Krakauer’s “The Death of an Innocent” from Outside magazine (see below) Venn Diagram Outside Magazine January 1993 Death of an Innocent How Christopher McCandless lost his way in the wilds By Jon Krakauer James Gallien had driven five miles out of Fairbanks when he spotted the hitchhiker standing in the snow beside the road, thumb raised high, shivering in the gray Alaskan dawn. A rifle protruded from the young man's pack, but he looked friendly enough; a hitchhiker with a Remington semiautomatic isn't the sort of thing that gives motorists pause in the 49th state. Gallien steered his four-by-four onto the shoulder and told him to climb in. The hitchhiker introduced himself as Alex. "Alex?" Gallien responded, fishing for a last name. "Just Alex," the young man replied, pointedly rejecting the bait. He explained that he wanted a ride as far as the edge of Denali National Park, where he intended to walk deep into the bush and "live off the land for a few months." Alex's backpack appeared to weigh only 25 or 30 pounds, which struck Gallien, an accomplished outdoorsman, as an improbably light load for a three-month sojourn in the backcountry, especially so early in the spring. -

Henry David Thoreau's Treatment of Nature in Walden

RESEARCH PAPER Literature Volume : 3 | Issue : 6 | June 2013 | ISSN - 2249-555X Henry David Thoreau‘s treatment of Nature in Walden KEYWORDS Dr. T. Eswar Rao P.G Dept. of English, Berhampur University, Bhanja Bihar, 76007 ABSTRACT Thoreau is one the greatest Nature-lovers in American literature. At Walden Pond he lived in the closest pos- sible proximity to Nature, and established a Wodrsworthian intimacy with all Nature’s aspects, features and moods. It would not be wrong to say that he is the Wordsworth of American literature, even though he wrote in prose and even though there is a basic difference he wrote in prose and even though there is a basic difference between Wordsworth’s treatment of Nature and Thoreau’s. Like Wordsworth’s, Thoreau’s love for Nature was profound and genuine. The relation- ship which Thoreau established between himself and Nature and which he wanted to be established between Nature and other human beings is one of the cardinal facts of Walden. Like Wordsworth, Thoreau treats Nature with imagination and feeling. Thoreau, the author of the famous, thought provoking book creates an animal cosmos that dramatizes his transcendental Walden is what Emerson calls Man Thinking. Walden is con- vision of the divinity of nature. sidered a masterpiece one of America’s greatest writers and philosophers; Thoreau hated cruelty and injustice as much Walden is neither an essay, nor philosophy, nor preaching; as he loved Nature. Walden is one of the great seminal book it is an account of the various meanings of nature as expe- of the19th century declares Joseph wood .The Krutch. -

Why Was There a Quaker School in Saffron Walden?

a Quaker School in Saffron Walden Why was there a Quaker School in Saffron Walden? Tony Watson his article is prompted by the 1825 Croydon: e expansion of north (l&MGM) was asked to find a new site. closure of Walden School, london led to health problems. e is meeting was a successor to the Tformerly the friends’ School, in school was moved to croydon where london & Middlesex Quarterly Meeting: July 2017, and addresses the question as education was developed. John Sharp was ‘Many visits were made in search of new to why there was a Quaker School in appointed Superintendent, and served premises. Even a brewery was inspected, Saffron Walden. e history of the school from 1844 to 1853. he recorded the however the buildings were unsuitable is largely recorded in various publications following ideals for the classroom which though the water excellent!’ 2 produced to celebrate anniversaries and formed a part of the foundation of the which are acknowledged below. as the school’s ethos: Move to Saffron Walden, 1879 school was originally founded in 1702, in 1. Never do a thing for a scholar, but teach John Woods, former head of the clerkenwell, london, it has a long history him to do it for himself. School, wrote in 1979 a history of the and this short article cannot do justice to 2. Never get out of patience with children; hundred years at Walden: its record in educating both Quaker and or rather never get out of patience with It started with typhoid. In October 1875 non-Quaker children.