Within “Walden” by Henry David Thoreau and “The Death of An

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![HUMS 4904A Schedule Mondays 11:35 - 2:25 [Each Session Is in Two Halves: a and B]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6562/hums-4904a-schedule-mondays-11-35-2-25-each-session-is-in-two-halves-a-and-b-86562.webp)

HUMS 4904A Schedule Mondays 11:35 - 2:25 [Each Session Is in Two Halves: a and B]

CARLETON UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF THE HUMANITIES Humanities 4904 A (Winter 2011) Mahatma Gandhi Across Cultures Mondays 11:35-2:25 Prof. Noel Salmond Paterson Hall 2A46 Paterson Hall 2A38 520-2600 ext. 8162 [email protected] Office Hours: Tuesdays 2:00 - 4:00 (Or by appointment) This seminar is a critical examination of the life and thought of one of the pivotal and iconic figures of the twentieth century, Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi – better known as the Mahatma, the great soul. Gandhi is a bridge figure across cultures in that his thought and action were inspired by both Indian and Western traditions. And, of course, in that his influence has spread across the globe. He was shaped by his upbringing in Gujarat India and the influences of Hindu and Jain piety. He identified as a Sanatani Hindu. Yet he was also influenced by Western thought: the New Testament, Henry David Thoreau, John Ruskin, Count Leo Tolstoy. We will read these authors: Thoreau, On Civil Disobedience; Ruskin, Unto This Last; Tolstoy, A Letter to a Hindu and The Kingdom of God is Within You. We will read Gandhi’s autobiography, My Experiments with Truth, and a variety of texts from his Collected Works covering the social, political, and religious dimensions of his struggle for a free India and an India of social justice. We will read selections from his commentary on the Bhagavad Gita, the book that was his daily inspiration and that also, ironically, was the inspiration of his assassin. We will encounter Gandhi’s clash over communal politics and caste with another architect of modern India – Bimrao Ambedkar, author of the constitution, Buddhist convert, and leader of the “untouchable” community. -

Into the Wild

Into the Wild Chapter Two Click to edit Master subtitle style Which of these sentences is best? A. Carrying nothing but a bag of rice, walking into the wilderness. B. Carrying nothing but a bag of rice, Chris walked into the wilderness. C. Chris walked into the wilderness, carrying nothing but a bag of rice. The Jack London Passage • Krakauer provides a quote from Jack London's White Fang about the mirthless (joyless) and merciless frozen Northern wilderness. • This quote sets the tone for the chilling struggle for survival which is about to unfold. Exposition: Setting • Blazed in the 1930s by an Alaskan miner, (Earl Pilgrim) the Stampede Trail originally led to Pilgrim's mining claims along Stampede Creek. • In the early 1960s, the trail was upgraded by Yutan Construction to an actual roadway meant to allow trucks to haul ore year-round from the mines. • Only 3 years later, the project was scrapped due to the harsh Alaskan conditions. Prime (and Illegal) Hunting • Moose hunters frequent the area where the bus lies because it is surrounded on three sides by protected wilderness preserves. • In September of 1992, by coincidence (fate?), three groups of people arrive at the normally deserted bus on the same day. – We know what they will find, but first they have to get there… • At this point in the season, the river is 75 feet across with swift currents. • The daring hunters (Thompson, Samel, and Swanson) drive through one by one, prepared to tow each other out with a strong winch. At the far bank, the hunters park their vehicles and continue on in the ATVs they carry in the back of the trucks. -

Thoreau As an Oblique Mirror: Jon Krakauer's Into the Wild

American Studies in Scandinavia, 47:1 (2015), pp. 40-60. Published by the Nordic Association for American Studies (NAAS). Thoreau as an Oblique Mirror: Jon Krakauer’s Into the Wild José Sánchez Vera Karlstad University Abstract: In his nonfiction biography of Christopher McCandless, Into the Wild, Jon Krakauer uses a plethora of references to Henry D. Thoreau. In this article I analyze Krakauer’s use of Thoreau’s economic ideas, liberalism, and view of nature and wil- derness. I argue that Krakauer blurs a pragmatic understanding of Thoreau and uses techniques of fiction to create an appealing story and characterize McCandless as a latter-day Thoreauvian transcendentalist. By doing so, Krakauer explains and de- fends the protagonist’s actions from criticism, thereby making him appear as a char- acter whose story is exceptional. Although the characterization of the protagonist as a follower of Thoreauvian ideals by means of a partial interpretation of Thoreau does not provide us with a better understanding of McCandless’s life, Krakauer’s extensive research and the critical self-reflection in the text produces a compelling nonfiction narrative. Moreover, the romantic image of Thoreau advanced by Krakauer reflects the preoccupations and issues that concerned Krakauer, or at least his times. Particu- larly, it reflects Krakauer’s own ideas concerning the negative effects of materialism on both ourselves and the natural world. Key words: Jon Krakauer, Henry David Thoreau, Into the Wild, nonfiction, nature, transcendentalism Into the Wild is Jon Krakauer’s nonfiction biography of Christopher Mc- Candless, a talented college graduate who inexplicably leaves his family, his friends, and all the comforts of civilization in search of ultimate free- dom, a nobler form of life closer to nature and divorced from the extreme materialism of American society. -

(Quakers) in Britain Testimonies Including Index of Epistles

Yearly Meeting of the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers) in Britain Testimonies including index of epistles Compiled for Yearly Meeting 2020 Q Logo - Sky - CMYK - Black Text.pdf 1 26.04.2016 04.55 pm C M Y CM MY CY CMY K Credit: Mike Pinches for BYM Pinches for Mike Credit: This booklet is part of ‘Proceedings of the Yearly Meeting of the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers) in Britain 2019’, a set of publications published for Yearly Meeting. The full set comprises: 1. The Yearly Meeting programme, with introductory material for Yearly Meeting 2019 and annual reports of Meeting for Sufferings, Quaker Stewardship Committee and other related bodies 2. Testimonies 3. Minutes, to be distributed after the conclusion of Yearly Meeting 4. The formal Trustees’ annual report including financial statements for the year ended December 2019 5. Tabular statement. All documents are available online at www.quaker.org.uk/ym. If these do not meet your accessibility needs, or the needs of someone you know, please email [email protected]. Printed copies of all documents will be available at Yearly Meeting. All Quaker faith & practice references are to the online edition, which can be found at www.quaker.org.uk/qfp. Yearly Meeting of the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers) in Britain Testimonies Contents Epistles 5 Introduction 6 Warren Adams 8 Judith Mary Effer 9 Marion Fairweather 11 Sheila J. Gatiss 12 Joyce Gee 14 Joan Gibson 16 David Henshaw 17 Kate Joyce 20 Richard Lacock 23 Lesley Parker 25 Erika Margarethe Zintl Pearce 27 Angela Maureen Pivac 30 Margaret Rowan 32 Peter Rutter 34 Margaret Slee 36 Rachel Smith 38 Claire Watkins 39 Allan N. -

Into the Wild

Into the Wild Chapters 1-7 Author’s Note • What does the author’s note tell us? – Timeline and Punchline – Tidbits of the journey/experience – Mistakes will plague the experiment – AsceGcism—deny worldly pleasures for spiritual elevaon – Themes of fathers/sons and young men/ challenges – Interpretaons of Chris McCandless Strategies • Strategies – Start with the end – Open chapters with notes/quotes/excerpts – Nonlinear—jumps in Gme and space— pieces of puzzle—put together fragments like detecGve or psychologist – Language—terse, uGlitarian, concrete imagery, stats/facts/maps/photos, travelogue Chapter 1 • Into the wild (April 28, 1992) • What does first notecard establish? 3 • Jim Gallien – Thoughts on Chris McCandless (Alexander Supertramp) 4 – Problems with journey into the wild 5 – Foreshadow—references to water Chapter 2 • Out of the wild • Reset of Naturalism (Jack London) and Transcendentalism (Henry David Thoreau) • What does Alaska conjure/connote? • Origin of the Fairbanks Bus 142 10 – Stampede Trail between Teklanika River (East) and Sushana River (West) —Pocket of Denali Naonal Park, Outside of Healy Chapter 2 • The discovery (Sept 6, 1992) – Irony – 6 people / 3 parGes – Facts of the end • Blue sleeping bag • 67 pounds • SOS note Chapter 3 • What does the West conjure/connote? • Carthage 15,18 • Cabaret 16 • Wayne Westerberg 16,19 • Revelaons of Chris / Alex – Tramps 17 – Physical 16 – EmoGonal 18 – Familial 19 • Car—Roadtrip/Odyssey—July/Aug 1990 22 Chapter 4 • Southwest journey – July 1990 – February 1991 • What are the associaons -

The Chris Mccandless Obsession Problem

The Chris McCandless Obsession Problem Diana Saverin, Outside Magazine, December 18, 2013 On the isolated shore of the Savage River, in the backcountry of interior Alaska, there‘s a small memorial to a deceased woman named Claire Ackermann. A pile of rocks sits on a metal plaque with an inscription that reads, in part: ―To stay put is to exist; to travel is to live.‖ Three years ago, Ackermann, 29, and her boyfriend, Etienne Gros, 27, tried to cross the Teklanika River, a couple of miles west from the Savage. They tied themselves to a rope that somebody had run from one bank to the other, to aid such attempts. The Teklanika is powerful in summertime, and about halfway across they lost their footing. The rope dipped into the water, and Ackermann and Gros, still tied on, were pulled under by its weight. Gros grabbed a knife, cut himself loose, and swam to shore. He waded back out to try and rescue Ackermann, but it was too late—she had already drowned. He cut her loose and swam with her body 300 yards downstream, where he dragged her to land on the river‘s far shore. His attempts at CPR were useless. Ackermann, who was from Switzerland, and Gros, a Frenchman, had been hiking the Stampede Trail, a route made famous by Christopher McCandless, who walked it in April 1992. Many people now know about McCandless and how the 24-year-old idealist bailed out of his middle- class suburban life, donated his $24,000 in savings to charity, and embarked on a two-year hitchhiking odyssey that led him to Alaska and the deserted Fairbanks City Transit bus number 142, which still sits, busted and rusting, 20 miles down the Stampede Trail. -

HOUSE RES COMMITTEE -1- April 5, 2010 WITNESS REGISTER

ALASKA STATE LEGISLATURE HOUSE RESOURCES STANDING COMMITTEE April 5, 2010 1:06 p.m. MEMBERS PRESENT Representative Craig Johnson, Co-Chair Representative Bryce Edgmon Representative Paul Seaton Representative David Guttenberg Representative Scott Kawasaki Representative Chris Tuck MEMBERS ABSENT Representative Mark Neuman, Co-Chair Representative Kurt Olson Representative Peggy Wilson COMMITTEE CALENDAR CONFIRMATION HEARING(S): Commercial Fisheries Entry Commission Bruce C. Twomley - Juneau - CONFIRMATION(S) ADVANCED Big Game Commercial Services Board Robert D. Mumford - Anchorage - CONFIRMATION(S) ADVANCED Board of Game Ben Grussendorf - Sitka Allen F. Barrette - Fairbanks - CONFIRMATION(S) ADVANCED PREVIOUS COMMITTEE ACTION No previous action to record HOUSE RES COMMITTEE -1- April 5, 2010 WITNESS REGISTER BRUCE C. TWOMLEY, Appointee Alaska Commercial Fisheries Entry Commission (CFEC) Juneau, Alaska POSITION STATEMENT: Testified as appointee to the Commercial Fisheries Entry Commission. ROBERT D. MUMFORD, Appointee Big Game Commercial Services Board Anchorage, Alaska POSITION STATEMENT: Testified as appointee to the Big Game Commercial Services Board. BEN GRUSSENDORF, Appointee Board of Game Sitka, Alaska POSITION STATEMENT: Testified as appointee to the Board of Game. ALLEN F. BARRETTE, Appointee Board of Game Sitka, Alaska POSITION STATEMENT: Testified as appointee to the Board of Game. VIRGIL UMPHENOUR Fairbanks, Alaska POSITION STATEMENT: Testified in support of Mr. Mumford's appointment to the Big Game Commercial Services Board. KELLY WALTERS Anchorage, Alaska POSITION STATEMENT: Testified in support of the appointment of Mr. Grussendorf to the Board of Game. TINA BROWN, Board Member Alaska Wildlife Alliance Juneau, Alaska POSITION STATEMENT: Testified in opposition to Mr. Barrette's appointment to the Board of Game. KARLA HART Juneau, Alaska POSITION STATEMENT: Expressed concerns with the appointment of Mr. -

From Engineering Hydrology to Earth System Science: Milestones in the Transformation of Hydrologic Science

Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci., 22, 1665–1693, 2018 https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-22-1665-2018 © Author(s) 2018. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. From engineering hydrology to Earth system science: milestones in the transformation of hydrologic science Murugesu Sivapalan1,* 1Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, Department of Geography and Geographic Information Science, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Urbana, Illinois 61801, USA * Invited contribution by Murugesu Sivapalan, recipient of the EGU Alfred Wegener Medal & Honorary Membership 2017. Correspondence: Murugesu Sivapalan ([email protected]) Received: 13 November 2017 – Discussion started: 15 November 2017 Revised: 2 February 2018 – Accepted: 5 February 2018 – Published: 7 March 2018 Abstract. Hydrology has undergone almost transformative hydrology to Earth system science, drawn from the work of changes over the past 50 years. Huge strides have been made several students and colleagues of mine, and discuss their im- in the transition from early empirical approaches to rigorous plication for hydrologic observations, theory development, approaches based on the fluid mechanics of water movement and predictions. on and below the land surface. However, progress has been hampered by problems posed by the presence of heterogene- ity, including subsurface heterogeneity present at all scales. எப்ெபாள் யார்யாரவாய் ் க் ேகட்ம் The inability to measure or map the heterogeneity every- அப்ெபாள் ெமய் ப்ெபாள் காண் ப த where prevented the development of balance equations and In whatever matter and from whomever heard, associated closure relations at the scales of interest, and has Wisdom will witness its true meaning. -

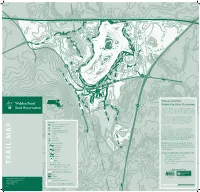

Walden Pond R O Oa W R D L Oreau’S O R Ty I a K N N U 226 O

TO MBTA FITCHBURG COMMUTER LINE ROUTE 495, ACTON h Fire d Sout Road North T 147 Fire Roa th Fir idge r Pa e e R a 167 Pond I R Pin i c o l Long Cove e ad F N Ice Fort Cove o or rt th Cove Roa Heywood’s Meadow d FIELD 187 l i Path ail Lo a w r Tr op r do e T a k e s h r F M E e t k a s a Heyw ’s E 187 i P 187 ood 206 r h d n a a w 167 o v o e T R n H e y t e v B 187 2 y n o a 167 w a 187 C y o h Little Cove t o R S r 167 d o o ’ H s F a e d m th M e loc Pa k 270 80 c e 100 I B a E e m a d 40 n W C Baker Bridge Road o EMERSON’S e Concord Road r o w s 60 F a n CLIFF i o e t c e R n l o 206 265 d r r o ’s 20 d t a o F d C Walden Pond R o oa w R d l oreau’s o r ty i a k n n u 226 o 246 Cove d C T d F Ol r o a O r i k l l d C 187 o h n h t THOREAU t c 187 a a HOUSE SITE o P P Wyman 167 r ORIGINAL d d 167 R l n e Meadow i o d ra P g . -

A New Look at Thoreau

ADDENDUM A NEW LOOK AT THOREAU In the summer of Thoreau did not put me to sleep. He shook me awake, 1984, as a college student hungry pointing me toward an alternative vision of the good life. to see the halls of power up close, I took a summer internship on Natural History, I saw just the thing to usher me blissfully into unconsciousness Capitol Hill. that night. Out of the corner of my eye, I’d spotted the bright green cover of It was heady Walden in the window of the museum bookshop. stuff for a 20-year-old. I shared a row Two years earlier, I’d been assigned to read Henry David Thoreau in American house with three other students a few Lit class and found him a colossal bore. His questioning of material gain left me blocks from the Capitol, passing the cold. I dreamed of a life after college that included more, not fewer, possessions. Library of Congress and Supreme I also wanted to be at the center of things, not sequestered in a shack by a pond. Court on my walk to work. Someone Walden seemed like a manual in how not to succeed. got me an insider tour of the White Finally, an author I’d endured in the classroom would have some use for me, his House, which allowed me to stick my prose as potent as a tranquilizer. I bought Walden from the Smithsonian and took head into the Oval Office and gaze it home, convinced that I carried literary laudanum in my hands. -

Agrarianism: an Ideology of the National FFA Organization

Journal of Agricultural Education Volume 54, Number 3, pp. 28 – 40 DOI: 10.5032/jae.2013.03028 Agrarianism: An Ideology of the National FFA Organization Michael J. Martin Colorado State University Tracy Kitchel University of Missouri The traditions of the National FFA Organization (FFA) are grounded in agrarianism. This ideology fo- cuses on the ability of farming and nature to develop citizens and integrity within people. Agrarianism has been an important thread of American rhetoric since the founding of country. The ideology has mor- phed over the last two centuries as the country developed from a nation of farmers to an industrial world power. The agrarian ideology that resonated in rural America during the formation of the FFA was southern agrarianism. Southern agrarian ideology argued for self-reliance and adherence to past tradi- tions. These concepts appear in the FFA traditions of the creed, opening ceremony, motto, and awards. The historical growth and success of the FFA within rural communities demonstrates the ability of the southern agrarian ideology to connect with contemporary rural values. However, the southern agrarian ideology may not connect with the culture of diverse, urban, or suburban students. Advisers of diverse, urban, or suburban FFA chapters may need to reconceptualize the FFA traditions to accommodate their students. Keywords: National FFA Organization; philosophy; ideology; agrarianism The theme Beyond Diversity to Cultural LaVergne, Larke, Elbert, & Jones, 2011). One Proficiency resonated at the 2011 American As- study highlighted how some non-FFA members sociation for Agricultural Education (AAAE) viewed FFA members as hicks (Phelps, Henry, conference. Fittingly, AAAE invited James & Bird, 2012). -

Into the Wild Libro Pdf Español

Into the wild libro pdf español Continue To the Wild Routes John KrakauerGenerous Biography Original English Edition Original title in the wild edition of VillardCompanhia das Letras Ciudad MichiganPais USA Publishing Date 1996 Pages 224Dition translated to spanishTitle K routes Wild Traduced Albert FreixaEditorial Editions BCity BarcelonaPa's SpainPages 285SerieEiger Dreams to Wild RoutesIn thin air (edited by Wikidata data) to wild routes (in its original English version) Into The Wild - book , written by John Krakower in 1995, which in 2007 was adapted into a movie directed by Sean Penn under the original name Into the Wild. Christopher McCandless, a young man from a wealthy family, in 1990, graduating from Emory University in Atlanta, decided to go on a journey without telling anyone about his purpose or his intentions. Two years later he was found dead in an Alaskan interior. His case was reported by Outside journalist John Krakover. The latter, interested in the motives and conditions that Chris experienced, decided to go even further into the story of this young man. To the wild routes, he almost completely tells the facts from the point of view of the last people with whom Chris communicated before entering the wild lands of Alaska, where he eventually found his death. In addition, the author adds excerpts from his life as a lover of nature and mountain life, citing the slight similarities he shares with Chris. At the same time, he is trying to clarify the key factors in the young man's life that led him to decide to follow this last path, completely moving away from his family and any hint of civilization.