Anarcho-Primitivism and Revolt Against Disintegration in Eugene O'neill's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![HUMS 4904A Schedule Mondays 11:35 - 2:25 [Each Session Is in Two Halves: a and B]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6562/hums-4904a-schedule-mondays-11-35-2-25-each-session-is-in-two-halves-a-and-b-86562.webp)

HUMS 4904A Schedule Mondays 11:35 - 2:25 [Each Session Is in Two Halves: a and B]

CARLETON UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF THE HUMANITIES Humanities 4904 A (Winter 2011) Mahatma Gandhi Across Cultures Mondays 11:35-2:25 Prof. Noel Salmond Paterson Hall 2A46 Paterson Hall 2A38 520-2600 ext. 8162 [email protected] Office Hours: Tuesdays 2:00 - 4:00 (Or by appointment) This seminar is a critical examination of the life and thought of one of the pivotal and iconic figures of the twentieth century, Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi – better known as the Mahatma, the great soul. Gandhi is a bridge figure across cultures in that his thought and action were inspired by both Indian and Western traditions. And, of course, in that his influence has spread across the globe. He was shaped by his upbringing in Gujarat India and the influences of Hindu and Jain piety. He identified as a Sanatani Hindu. Yet he was also influenced by Western thought: the New Testament, Henry David Thoreau, John Ruskin, Count Leo Tolstoy. We will read these authors: Thoreau, On Civil Disobedience; Ruskin, Unto This Last; Tolstoy, A Letter to a Hindu and The Kingdom of God is Within You. We will read Gandhi’s autobiography, My Experiments with Truth, and a variety of texts from his Collected Works covering the social, political, and religious dimensions of his struggle for a free India and an India of social justice. We will read selections from his commentary on the Bhagavad Gita, the book that was his daily inspiration and that also, ironically, was the inspiration of his assassin. We will encounter Gandhi’s clash over communal politics and caste with another architect of modern India – Bimrao Ambedkar, author of the constitution, Buddhist convert, and leader of the “untouchable” community. -

(Quakers) in Britain Testimonies Including Index of Epistles

Yearly Meeting of the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers) in Britain Testimonies including index of epistles Compiled for Yearly Meeting 2020 Q Logo - Sky - CMYK - Black Text.pdf 1 26.04.2016 04.55 pm C M Y CM MY CY CMY K Credit: Mike Pinches for BYM Pinches for Mike Credit: This booklet is part of ‘Proceedings of the Yearly Meeting of the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers) in Britain 2019’, a set of publications published for Yearly Meeting. The full set comprises: 1. The Yearly Meeting programme, with introductory material for Yearly Meeting 2019 and annual reports of Meeting for Sufferings, Quaker Stewardship Committee and other related bodies 2. Testimonies 3. Minutes, to be distributed after the conclusion of Yearly Meeting 4. The formal Trustees’ annual report including financial statements for the year ended December 2019 5. Tabular statement. All documents are available online at www.quaker.org.uk/ym. If these do not meet your accessibility needs, or the needs of someone you know, please email [email protected]. Printed copies of all documents will be available at Yearly Meeting. All Quaker faith & practice references are to the online edition, which can be found at www.quaker.org.uk/qfp. Yearly Meeting of the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers) in Britain Testimonies Contents Epistles 5 Introduction 6 Warren Adams 8 Judith Mary Effer 9 Marion Fairweather 11 Sheila J. Gatiss 12 Joyce Gee 14 Joan Gibson 16 David Henshaw 17 Kate Joyce 20 Richard Lacock 23 Lesley Parker 25 Erika Margarethe Zintl Pearce 27 Angela Maureen Pivac 30 Margaret Rowan 32 Peter Rutter 34 Margaret Slee 36 Rachel Smith 38 Claire Watkins 39 Allan N. -

The Social Ecology of Artisanal Mining: Between Romanticisation and Anathema Saleem H

5 The social ecology of artisanal mining: Between romanticisation and anathema Saleem H. Ali Artisanal and small-scale mining (ASM) has existed for millennia, and is ingrained in many cultural traditions. However, as this book’s first four chapters have demonstrated, the activity has often faced challenges of acceptance by mainstream institutions because it occupies an interstitial space ‘between the pick and the plough’. It is at once an extractive sector but is also practised as a seasonal activity of agrarian peasants. It may not have all the hallmarks of a formal enterprise, but it is also seldom anarchic plundering of a resource. Thus, in this chapter, I attempt to negotiate through these seemingly conflicting elements of ASM by offering a synthetic conceptual anchor for the preceding chapters. I am guided in this task by an acute recognition that environmental concerns about ASM would need to be addressed in any effective framing of its social development imperative. Development donors have considered ASM as suitable for technical interventions to improve yield of minerals or alternative techniques for safer extraction. The World Bank and the Communities and Small-Scale Mining (CASM) program1 was operational from 2000 to 2010, and developed a 1 Details of the CASM program of work can be found at World Bank (2008). 117 BeTWeeN THe PLOUGH AND THe PICK broad repertoire of information exchange in this arena. The United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO) and Swiss Development Agency’s efforts to focus on the use of mercury in ASM gold-mining are examples of such undertakings. Mercury reduction efforts have been spurred by the advent of the Minamata Convention on Mercury Reduction that has thus far been signed by over 128 countries, and ratified by 88 (as of January 2018).2 The Convention recognises that mercury usage in artisanal and small-scale mining will likely be a challenge for many more years to come, given the remote locations of the mining sites and the relatively low cost of mercury worldwide. -

From Engineering Hydrology to Earth System Science: Milestones in the Transformation of Hydrologic Science

Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci., 22, 1665–1693, 2018 https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-22-1665-2018 © Author(s) 2018. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. From engineering hydrology to Earth system science: milestones in the transformation of hydrologic science Murugesu Sivapalan1,* 1Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, Department of Geography and Geographic Information Science, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Urbana, Illinois 61801, USA * Invited contribution by Murugesu Sivapalan, recipient of the EGU Alfred Wegener Medal & Honorary Membership 2017. Correspondence: Murugesu Sivapalan ([email protected]) Received: 13 November 2017 – Discussion started: 15 November 2017 Revised: 2 February 2018 – Accepted: 5 February 2018 – Published: 7 March 2018 Abstract. Hydrology has undergone almost transformative hydrology to Earth system science, drawn from the work of changes over the past 50 years. Huge strides have been made several students and colleagues of mine, and discuss their im- in the transition from early empirical approaches to rigorous plication for hydrologic observations, theory development, approaches based on the fluid mechanics of water movement and predictions. on and below the land surface. However, progress has been hampered by problems posed by the presence of heterogene- ity, including subsurface heterogeneity present at all scales. எப்ெபாள் யார்யாரவாய் ் க் ேகட்ம் The inability to measure or map the heterogeneity every- அப்ெபாள் ெமய் ப்ெபாள் காண் ப த where prevented the development of balance equations and In whatever matter and from whomever heard, associated closure relations at the scales of interest, and has Wisdom will witness its true meaning. -

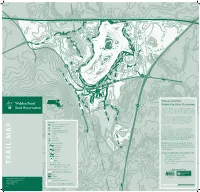

Walden Pond R O Oa W R D L Oreau’S O R Ty I a K N N U 226 O

TO MBTA FITCHBURG COMMUTER LINE ROUTE 495, ACTON h Fire d Sout Road North T 147 Fire Roa th Fir idge r Pa e e R a 167 Pond I R Pin i c o l Long Cove e ad F N Ice Fort Cove o or rt th Cove Roa Heywood’s Meadow d FIELD 187 l i Path ail Lo a w r Tr op r do e T a k e s h r F M E e t k a s a Heyw ’s E 187 i P 187 ood 206 r h d n a a w 167 o v o e T R n H e y t e v B 187 2 y n o a 167 w a 187 C y o h Little Cove t o R S r 167 d o o ’ H s F a e d m th M e loc Pa k 270 80 c e 100 I B a E e m a d 40 n W C Baker Bridge Road o EMERSON’S e Concord Road r o w s 60 F a n CLIFF i o e t c e R n l o 206 265 d r r o ’s 20 d t a o F d C Walden Pond R o oa w R d l oreau’s o r ty i a k n n u 226 o 246 Cove d C T d F Ol r o a O r i k l l d C 187 o h n h t THOREAU t c 187 a a HOUSE SITE o P P Wyman 167 r ORIGINAL d d 167 R l n e Meadow i o d ra P g . -

A New Look at Thoreau

ADDENDUM A NEW LOOK AT THOREAU In the summer of Thoreau did not put me to sleep. He shook me awake, 1984, as a college student hungry pointing me toward an alternative vision of the good life. to see the halls of power up close, I took a summer internship on Natural History, I saw just the thing to usher me blissfully into unconsciousness Capitol Hill. that night. Out of the corner of my eye, I’d spotted the bright green cover of It was heady Walden in the window of the museum bookshop. stuff for a 20-year-old. I shared a row Two years earlier, I’d been assigned to read Henry David Thoreau in American house with three other students a few Lit class and found him a colossal bore. His questioning of material gain left me blocks from the Capitol, passing the cold. I dreamed of a life after college that included more, not fewer, possessions. Library of Congress and Supreme I also wanted to be at the center of things, not sequestered in a shack by a pond. Court on my walk to work. Someone Walden seemed like a manual in how not to succeed. got me an insider tour of the White Finally, an author I’d endured in the classroom would have some use for me, his House, which allowed me to stick my prose as potent as a tranquilizer. I bought Walden from the Smithsonian and took head into the Oval Office and gaze it home, convinced that I carried literary laudanum in my hands. -

What Is Anarcho-Primitivism?

The Anarchist Library Anti-Copyright What is Anarcho-Primitivism? Anonymous Anonymous What is Anarcho-Primitivism? 2005 Retrieved on 11 December 2010 from blackandgreenbulletin.blogspot.com theanarchistlibrary.org 2005 Rousseau, Jean Jacques. (2001). On the Inequality among Mankind. Vol. XXXIV, Part 3. The Harvard Classics. (Origi- nal 1754). Retrieved November 13, 2005, from Bartleby.com: www.bartleby.com Sahlins, Marshall. (1972). “The Original Affluent Society.” 1–39. In Stone Age Economics. Hawthorne, New York: Aldine de Gruyter. Sale, Kirkpatrick. (1995a). Rebels against the future: the Luddites and their war on the Industrial Revolution: lessons for the computer age. New York: Addison-Wesley. — . (1995b, September 25). “Unabomber’s Secret Treatise: Is There Method In His Madness?” The Nation, 261, 9, 305–311. “Situationism”. (2002). The Art Industri Group. Retrieved Novem- ber 15, 2005, from Art Movements Directory: www.artmovements.co.uk Stobbe, Mike (2005, Dec 8). “U.S. Life Expectancy Hits All- Time High.” Retrieved December 8, 2005, from Yahoo! News: news.yahoo.com — Tucker, Kevin. (2003, Spring). “The Spectacle of the Symbolic.” Species Traitor: An Insurrectionary Anarcho-Primitivist Journal, 3, 15–21. U.S. Forestland by Age Class. Retrieved December 7, 2005, from Endgame Research Services: www.endgame.org Zerzan, John. (1994). Future Primitive and Other Essays. Brooklyn: Autonomedia. — . (2002, Spring). “It’s All Coming Down!” In Green Anarchy, 8, 3–3. — . (2002). Running on Emptiness: The Pathology of Civilisation. Los Angeles: Feral House. Zinn, Howard. (1997). “Anarchism.” 644–655. In The Zinn Reader: Writings on disobedience and democracy. New York: Seven Sto- ries. 23 Kassiola, Joel Jay. (1990) The Death of Industrial Civilization: The Limits to Economic Growth and the Repoliticization of Advanced Industrial Society. -

Agrarianism: an Ideology of the National FFA Organization

Journal of Agricultural Education Volume 54, Number 3, pp. 28 – 40 DOI: 10.5032/jae.2013.03028 Agrarianism: An Ideology of the National FFA Organization Michael J. Martin Colorado State University Tracy Kitchel University of Missouri The traditions of the National FFA Organization (FFA) are grounded in agrarianism. This ideology fo- cuses on the ability of farming and nature to develop citizens and integrity within people. Agrarianism has been an important thread of American rhetoric since the founding of country. The ideology has mor- phed over the last two centuries as the country developed from a nation of farmers to an industrial world power. The agrarian ideology that resonated in rural America during the formation of the FFA was southern agrarianism. Southern agrarian ideology argued for self-reliance and adherence to past tradi- tions. These concepts appear in the FFA traditions of the creed, opening ceremony, motto, and awards. The historical growth and success of the FFA within rural communities demonstrates the ability of the southern agrarian ideology to connect with contemporary rural values. However, the southern agrarian ideology may not connect with the culture of diverse, urban, or suburban students. Advisers of diverse, urban, or suburban FFA chapters may need to reconceptualize the FFA traditions to accommodate their students. Keywords: National FFA Organization; philosophy; ideology; agrarianism The theme Beyond Diversity to Cultural LaVergne, Larke, Elbert, & Jones, 2011). One Proficiency resonated at the 2011 American As- study highlighted how some non-FFA members sociation for Agricultural Education (AAAE) viewed FFA members as hicks (Phelps, Henry, conference. Fittingly, AAAE invited James & Bird, 2012). -

Green Anarchy

GREENGREEN ANARCHYANARCHY AnAn Anti-CivilizationAnti-Civilization JournalJournal ofof TheoryTheory andand ActionAction www.greenanarchy.org SPRING/ SUMMER 2008 we live to live ISSUE #25 (i guess you could say we are “pro-lifers”) GREEN ANARCHY PO BOX 11331 Eugene, OR 97440 [email protected] $4 USA, $6 CANADA, $7 EUROPE, $8 WORLD FREE TO U.S.PRISONERS Direct Action Anarchist Resistance, pg 26 ContentsContents:: Ecological Defense and Animal Liberation, pg 40 Issue #25 Spring/Summer 2008 Indigenous Struggles, pg 48 Anti-Capitalist and Anti-State Battles, pg 54 Prisoner Escapes and Uprisings, pg 62 Articles Symptoms of the System’s Meltdown, pg 67 Silence byJohn Zerzan, pg 4 Straight Lines Don’t Work Any More Sections by Rebelaze, pg 6 Welcome to Green Anarchy, pg 2 Connecting to Place In the Land of the Lost: Fragment #42-44, pg 46 Questions for the Nomadic Wanderers The Garden of Peculiarities: by Sal Insieme, pg 8 State Repression News, pg 70 Hope Against Hope: Why Progressivism is as Useless Reviews, pg 74 as Leftism by Tara Specter, pg 12 News from the Balcony with Waldorf and Statler, pg 80 Sermon on the Cyber Mount Letters, pg 86 by The Honorable Reverend Black A. Hole,pg 14 Subscriber and Distributor Info, pg 90 Second-Best Life: Real Virtuality Green Anarchy Distro, pg 90 byJohn Zerzan, pg 16 Announcements, pg 92 Canaries In the Clockwork by earth-ling-gerring, pg 17 A Specious Species by C.E. Hayes, pg 18 Alone Together: the City and its Inmates .. .. .. inin thethe midstmidst ofof activity,activity, by John Zerzan, pg 20 therethere is a blurring between The End Of Slavery: Urban Scout On Creating A World thethe solosolo and the swarm. -

Agrarian Anarchism and Authoritarian Populism: Towards a More (State-)Critical ‘Critical Agrarian Studies’

The Journal of Peasant Studies ISSN: 0306-6150 (Print) 1743-9361 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/fjps20 Agrarian anarchism and authoritarian populism: towards a more (state-)critical ‘critical agrarian studies’ Antonio Roman-Alcalá To cite this article: Antonio Roman-Alcalá (2020): Agrarian anarchism and authoritarian populism: towards a more (state-)critical ‘critical agrarian studies’, The Journal of Peasant Studies, DOI: 10.1080/03066150.2020.1755840 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2020.1755840 © 2020 The Author(s). Published by Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group Published online: 20 May 2020. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 3209 View related articles View Crossmark data Citing articles: 4 View citing articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=fjps20 THE JOURNAL OF PEASANT STUDIES https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2020.1755840 FORUM ON AUTHORITARIAN POPULISM AND THE RURAL WORLD Agrarian anarchism and authoritarian populism: towards a more (state-)critical ‘critical agrarian studies’* Antonio Roman-Alcalá International Institute of Social Studies, The Hague, Netherlands ABSTRACT KEYWORDS This paper applies an anarchist lens to agrarian politics, seeking to Anarchism; authoritarian expand and enhance inquiry in critical agrarian studies. populism; critical agrarian Anarchism’s relevance to agrarian processes is found in three studies; state theory; social general areas: (1) explicitly anarchist movements, both historical movements; populism; United States of America; and contemporary; (2) theories that emerge from and shape these moral economy movements; and (3) implicit anarchism found in values, ethics, everyday practices, and in forms of social organization – or ‘anarchistic’ elements of human social life. -

John Zerzan Organized Labor Versus "The Revolt Against Work"

John Zerzan Organized labor versus "the revolt against work" Serious commentators on the labor upheavals of the Depression years seem to agree that disturbances of all kinds, including the wave of sit-down strikes of 1936 and 1937, were caused by the 'speed-up' above all. Dissatisfaction among production workers with their new CIO unions set in early, however, mainly because the unions made no efforts to challenge management's right to establish whatever kind of work methods and working conditions they saw fit. The 1945 Trends in Collective Bargaining study noted that "by around 1940" the labor leader had joined the business leader as an object of "widespread cynicism" to the American employee. Later in the 1940s C. Wright Mills, in his The New Men of Power: Amenca's Labor Leaders, described the union's role thusly: "the integration of union with plant means that the union takes over much of the company's personnel work, becoming the discipline agent of the rank-and-file." In the mid-1950s, Daniel Bell realized that unionization had not given workers control over their job lives. Struck by the huge, Spontaneous walk-out at River Rouge in July. 1949, over the speed of the Ford assembly line, he noted that "sometimes the constraints of work explode with geyser suddenness." And as Bell's Work and Its Discontents (1956) bore witness that "the revolt against work is widespread and takes many forms, “so had Walker and Guest's Harvard study, The Man on the Assembly Line (1953), testified to the resentment and resistance of the man on the line. -

Download Green Anarchy #13

CivilizationCivilization isis thethe amputationamputation ofof everythingeverything thatthat everever happenedhappened toto us.us. AnAn experimentexperiment createdcreated byby aliensaliens unableunable toto havehave sex.sex. CivilizationCivilization isis thethe molestationmolestation GREENGREEN ANARCHYANARCHY anan anti-civilizationanti-civilization journaljournal ofof theorytheory andand actionaction ofof everythingeverything wewe couldcould be.be. AA giantgiant repressionrepression meltingmelting intointo suppressionsuppression ISSUE #13 So that YOU never say what YOU mean. So that YOU never say what YOU mean. SUMMER 2003 Civilization is breathing down our necks Civilization is breathing down our necks $3 USA $4 CAN $5 WORLD SplittingSplitting usus apart.apart. FREE TO PRISONERS WeWe areare wreckagewreckage withwith beatingbeating hearts.hearts. CivilizationCivilization isis aa cancan ofof hairsprayhairspray SprayingSpraying forfor thethe senselesssenseless vainvain IntoInto aa hairnethairnet ...... OnlyOnly everever meantmeant toto bebe waves.waves. Civilization,Civilization, genocidegenocide beliefs,beliefs, MoralisticMoralistic See-throughSee-through lacelace blousesblouses Missiles,Missiles, ballisticballistic LackadaisicalLackadaisical MelancholyMelancholy redred lipsticklipstick WhenWhen oneone feelsfeels nauseous,nauseous, ButBut doesndoesn’’tt feelfeel sick.sick. CivilizationCivilization knewknew whowho youyou werewere beforebefore youyou werewere eveneven bornborn ForgaveForgave YouYou whenwhen youyou thoughtthought YouYou neededneeded