Anarchism and Environmental Philosophy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reassembling the Anarchist Critique of Technology Zachary M

Potential, Power and Enduring Problems: Reassembling the Anarchist Critique of Technology Zachary M. Loeb* Abstract Within anarchist thought there is a current that treats a critique of technology as a central component of a broader critique of society and modernity. This tendency – which can be traced through the works of Peter Kropotkin, Rudolf Rocker, and Murray Bookchin – treats technologies as being thoroughly nested within sets of powerful social relations. Thus, it is not that technology cannot provide ‘plenty for all’ but that technology is bound up in a system where priorities other than providing plenty win out. This paper will work to reassemble the framework of this current in order to demonstrate the continuing strength of this critique. I. Faith in technological progress has provided a powerful well of optimism from which ideologies as disparate as Marxism and neoliberal capitalism have continually drawn. Indeed, the variety of machines and techniques that are grouped together under the heading “technology” often come to symbolize the tools, both * Zachary Loeb is a writer, activist, librarian, and terrible accordion player. He earned his MSIS from the University of Texas at Austin, and is currently working towards an MA in the Media, Culture, and Communications department at NYU. His research areas include the critique of technology, media refusal and resistance to technology, ethical implications of technology, as well as the intersection of library science with the STS field. 87 literally and figuratively, which a society uses to construct a modern, better, world. That technologically enhanced modern societies remain rife with inequity and oppression, while leaving a trail of toxic e-waste in their wake, is treated as an acceptable tradeoff for progress – while assurances are given that technological solutions will soon appear to solve the aforementioned troubles. -

Murray Bookchin´S Libertarian Municipalism

CONCEPTOS Y FENÓMENOS FUNDAMENTALES DE NUESTRO TIEMPO UNAM UNIVERSIDAD NACIONAL AUTÓNOMA DE MÉXICO INSTITUTO DE INVESTIGACIONES SOCIALES MURRAY BOOKCHIN´S LIBERTARIAN MUNICIPALISM JANET BIEHL AGOSTO 2019 1 MURRAY BOOKCHIN’S LIBERTARIAN MUNICIPALISM By Janet Biehl The lifelong project of the American social theorist Murray Bookchin (1921–2006) was to try to perpetuate the centuries-old revolutionary socialist tradition. Born to socialist revolutionary parents in the Bronx, New York, he joined the international Communist movement as a Young Pioneer in 1930, then was inducted into the Young Communist League in 1934, where he trained to become a young commissar for the coming proletarian revolution. Impatient with traditional secondary education, he received a thoroughgoing education in Marxism-Leninism at the Workers School in lower Manhattan, where he immersed himself in dialectical materialism and the labor theory of value. But in the summer of 1939, when Stalin’s Soviet Union formed a pact with Nazi Germany, he cut his ties with the party to join the Trotskyists, who expected World War II to end in international proletarian revolution. When the war ended with no such revolution, many radical socialists of his generation abandoned the Left altogether.1 But Bookchin refused to give up on the socialist revolutionary project, or abandon the goal of replacing barbarism with socialism. Instead, in the 1950s, he set out to renovate leftist thought for the current era. He concluded that the new revolutionary arena would be not the factory but the city; that the new revolutionary agent would be not the industrial worker but the citizen; that the basic institution of the new society must be, not the dictatorship of the proletariat, but the citizens’ assembly in a face-to-face democracy; and that the limits of capitalism must be ecological. -

Social Ecology and Communalism

Murray Bookchin Bookchin Murray $ 12,95 / £ xx,xx Social Ecology and Communalism Replace this text Murray Bookchin ocial cology Social Ecology and Communalism and Communalism Social Ecology S E and Communalism AK Press Social Ecology and Communalism Murray Bookchin Social Ecology and Communalism Bookchin, Murray Social Ecology and Communalism Library of Congress Control Number 2006933557 ISBN 978-1-904859-49-9 Published by AK Press © Eirik Eiglad and Murray Bookchin 2006 AK Press 674–A 23rd St. Oakland, CA 94612 USA www.akpress.org [email protected] AK Press UK PO Box 12766 Edinburgh, EH8 9YE Scotland (0131) 555–5165 www.akuk.com [email protected] Design and layout by Eirik Eiglad Contents An Introduction to Social Ecology and Communalism 7 What is Social Ecology? 19 Radical Politics in an Era of Advanced Capitalism 53 The Role of Social Ecology in a Period of Reaction 68 The Communalist Project 77 After Murray Bookchin 117 An Introduction to Social Ecology and Communalism We are standing at a crucial crossroads. Not only does the age- old “social question” concerning the exploitation of human labor remain unresolved, but the plundering of natural resources has reached a point where humanity is also forced to politically deal with an “ecological question.” Today, we have to make conscious choices about what direction society should take, to properly meet these challenges. At the same time, we see that our very ability to make the necessary choices are being undermined by an incessant centralization of economic and political power. Not only is there a process of centralization in most modern nation states that divests humanity of any control over social affairs, but power is also gradually being transferred to transnational institutions. -

Bookchin's Libertarian Municipalism

BOOKCHIN’S LIBERTARIAN MUNICIPALISM Janet BIEHL1 ABSTRACT: The purpose of this article is to present the Libertarian Municipalism Theory developed by Murray Bookchin. The text is divided into two sections. The first section presents the main precepts of Libertarian Municipalism. The second section shows how Bookchin’s ideas reached Rojava in Syria and is influencing the political organization of the region by the Kurds. The article used the descriptive methodology and was based on the works of Murray Bookchin and field research conducted by the author over the years. KEYWORDS: Murray Bookchin. Libertarian Municipalism. Rojava. Introduction The lifelong project of the American social theorist Murray Bookchin (1921-2006) was to try to perpetuate the centuries-old revolutionary socialist tradition. Born to socialist revolutionary parents in the Bronx, New York, he joined the international Communist movement as a Young Pioneer in 1930 and trained to become a young commissar for the coming proletarian revolution. Impatient with traditional secondary education, he received a thoroughgoing education in Marxism-Leninism at the Workers School in lower Manhattan, immersing himself in dialectical materialism and the labor theory of value. But by the time Stalin’s Soviet Union formed a pact with Nazi Germany (in the sum- mer of 1939), he cut his ties with the party to join the Trotskyists, who expected World War II to end in international proletarian revolutions. When the war 1 Janet Biehl is an American political writer who is the author of numerous books and articles associated with social ecology, the body of ideas developed and publicized by Murray Bookchin. -

Leaving the Left Behind 115 Post-Left Anarchy?

Anarchy after Leftism 5 Preface . 7 Introduction . 11 Chapter 1: Murray Bookchin, Grumpy Old Man . 15 Chapter 2: What is Individualist Anarchism? . 25 Chapter 3: Lifestyle Anarchism . 37 Chapter 4: On Organization . 43 Chapter 5: Murray Bookchin, Municipal Statist . 53 Chapter 6: Reason and Revolution . 61 Chapter 7: In Search of the Primitivists Part I: Pristine Angles . 71 Chapter 8: In Search of the Primitivists Part II: Primitive Affluence . 83 Chapter 9: From Primitive Affluence to Labor-Enslaving Technology . 89 Chapter 10: Shut Up, Marxist! . 95 Chapter 11: Anarchy after Leftism . 97 References . 105 Post-Left Anarchy: Leaving the Left Behind 115 Prologue to Post-Left Anarchy . 117 Introduction . 118 Leftists in the Anarchist Milieu . 120 Recuperation and the Left-Wing of Capital . 121 Anarchy as a Theory & Critique of Organization . 122 Anarchy as a Theory & Critique of Ideology . 125 Neither God, nor Master, nor Moral Order: Anarchy as Critique of Morality and Moralism . 126 Post-Left Anarchy: Neither Left, nor Right, but Autonomous . 128 Post-Left Anarchy? 131 Leftism 101 137 What is Leftism? . 139 Moderate, Radical, and Extreme Leftism . 140 Tactics and strategies . 140 Relationship to capitalists . 140 The role of the State . 141 The role of the individual . 142 A Generic Leftism? . 142 Are All Forms of Anarchism Leftism . 143 1 Anarchists, Don’t let the Left(overs) Ruin your Appetite 147 Introduction . 149 Anarchists and the International Labor Movement, Part I . 149 Interlude: Anarchists in the Mexican and Russian Revolutions . 151 Anarchists in the International Labor Movement, Part II . 154 Spain . 154 The Left . 155 The ’60s and ’70s . -

John Zerzan Organized Labor Versus "The Revolt Against Work"

John Zerzan Organized labor versus "the revolt against work" Serious commentators on the labor upheavals of the Depression years seem to agree that disturbances of all kinds, including the wave of sit-down strikes of 1936 and 1937, were caused by the 'speed-up' above all. Dissatisfaction among production workers with their new CIO unions set in early, however, mainly because the unions made no efforts to challenge management's right to establish whatever kind of work methods and working conditions they saw fit. The 1945 Trends in Collective Bargaining study noted that "by around 1940" the labor leader had joined the business leader as an object of "widespread cynicism" to the American employee. Later in the 1940s C. Wright Mills, in his The New Men of Power: Amenca's Labor Leaders, described the union's role thusly: "the integration of union with plant means that the union takes over much of the company's personnel work, becoming the discipline agent of the rank-and-file." In the mid-1950s, Daniel Bell realized that unionization had not given workers control over their job lives. Struck by the huge, Spontaneous walk-out at River Rouge in July. 1949, over the speed of the Ford assembly line, he noted that "sometimes the constraints of work explode with geyser suddenness." And as Bell's Work and Its Discontents (1956) bore witness that "the revolt against work is widespread and takes many forms, “so had Walker and Guest's Harvard study, The Man on the Assembly Line (1953), testified to the resentment and resistance of the man on the line. -

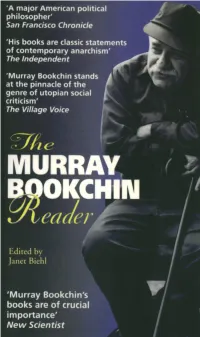

The Murray Bookchin Reader

The Murray Bookchin Reader We must always be on a quest for the new, for the potentialities that ripen with the development of the world and the new visions that unfold with them. An outlook that ceases to look for what is new and potential in the name of "realism" has already lost contact with the present, for the present is always conditioned by the future. True development is cumulative, not sequential; it is growth, not succession. The new always embodies the present and past, but it does so in new ways and more adequately as the parts of a greater whole. Murray Bookchin, "On Spontaneity and Organization," 1971 The Murray Bookchin Reader Edited by Janet Biehl BLACK ROSE BOOKS Montreal/New York London Copyright © 1999 BLACK ROSE BOOKS No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form, by any means electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system-without written permission from the publisher, or, in the case of photocopying or other reprographic copying, a license from the Canadian Reprography Collective, with the exception of brief passages quoted by a reviewer in a newspaper or magazine. Black Rose Books No. BB268 Hardcover ISBN: 1-55164-119-4 (bound) Paperback ISBN: 1-55164-118-6 (pbk.) Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 98-71026 Canadian Cataloguing in Publication Data Bookchin, Murray, 1921- Murray Bookchin reader Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 1-55164-119-4 (bound). ISBN 1-55164-118-6 (pbk.) 1. Libertarianism. 2. Environmentalism. 3. Human ecology. -

SOCIAL ANARCHISM OR LIFESTYLE ANARCHISM Murray 'Bookchin

SOCIAL ANARCHISM OR LIFESTYLE ANARCHISM AN UNB.RIDGEABLE CHASM Murray 'Bookchin AK PRESS © Copyright: 1995 Murray Bookchin Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Bookchin,Murray, 1921- Social anarchism or lifestyle anarchism : the unbridgeable chasm / byMurray Bookchin. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 1-873176-83-X (pbk.) 1. Anarchism. 2. Social problems. 3. Individualism. 4. Personalism. HX833.B635 1995 320.5'7-dc20 95-41903 CIP British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this title is available fromthe British Library . First published in 1995 by AK Press AK Press 22 Lutton Place P.O. Box 40682 Edinburgh, Scotland San Francisco, CA EH8 9PE 94140-0682 The publication of this volume was in part made possible by the generosity of Stefan Andreas Store, Chris Atton, Andy Hibbs, Stephen JohnAd ams, and the Friends of AK Press. Typeset and design donated by Freddie Baer. CONTENTS A Short Note to the Reader .......................................................... 1 Social Anarchism or Lifestyle Anarchism ................................. 4 The Left That Was: A Personal Reflection................................... ............................... 66 A NOTE TO THE READER This short work was written to deal with the fact that anarchism stands at a turning point in its long and turbulent history. At a time when popular distrust of the state has reached extraordinary proportions in many countries; when thedivision of society among a handful of opulently wealthy individuals and corporations contrasts sharply with the growing impover ishment of millions of people on a scale unprecedentedsince the Great Depression decade; when the intensity of exploitation has forced people in growing numbers to accept a work week of a length typical of the last century - anarchists have formed neither a coherent program nor a revolutionary organizationto provide a direction for the mass discontent that contemporary society is creating. -

John Zerzan and the Primitive Confusion, by En Attendant: a Review

Library.Anarhija.Net John Zerzan and the primitive confusion, by En Attendant: A Review Paul Petard 2004 Paul Petard reviews a pamphlet criticising the primitivism of John Zerzan. This Chronos pamphlet, John Zerzan and the primitive confusion is a reprint of a French text which was translated in September 2000 to coincide with a talk in London by the political neo-primitivist John Zerzan. The talk was hosted by U.K. Green Anarchist and Paul Petard Zerzan’s subject was the Green Anarchist movement in America. John Zerzan and the primitive confusion, by En Attendant: A The text dealt critically with two of John Zerzan’s books, “Future Review Primitive” and “Elements of Refusal”, and criticised them for being 2004 an ideological re-writing of the history of humanity. I made the mistake myself of going to the talk in London, and Retrieved on December 22, 2009 from libcom.org I was disappointed to find Zerzan, and more particularly his U.K. Green Anarchist hosts, talking some tiresome tosh against all tech- lib.anarhija.net nology, against all towns and cities, against any agriculture except the most basic smallest scale subsistence horticulture, against elec- tricity, against language, rationality, logic, against any large or so- phisticated human interaction. The only valid thing for them being very small neo-primitive subsistence groups and isolated individ- uals as a compulsory universal model for everyone. All those who don’t conform to this are to be despised and regarded as the enemy. As I have argued before elsewhere, I am opposed to the despotic policy proposal of some “communists” that hermits ought to be eaten for protein because they are outside community, to the con- trary I am very much in favour of leaving alone the eccentric indi- vidualists and isolationists and those who need a bit of temporary solitude. -

Technology Is Capital: Fifth Estate's Critique of the Megamachine

4 Steve Millett Technology is capital: Fifth Estate’s critique of the megamachine Introduction ‘How do we begin to discuss something as immense as technology?’, writes T. Fulano at the beginning of his essay ‘Against the megamachine’ (1981a: 4). Indeed, the degree to which the technological apparatus penetrates all elements of contemporary society does make such an undertaking a daunting one. Nevertheless, it is an undertaking that the US journal and collective Fifth Estate has attempted. In so doing, it has developed arguably the most sophisticated and challenging anarchist approach to technology currently available.1 Starting from the late 1970s, the Fifth Estate (hereafter FE) began to put forward the argument that the technologies of capitalism cannot be separated from the socioeconomic system itself. Inspired and influenced by a number of writers, including Karl Marx, Jacques Ellul and Jacques Camatte, it began to conceptualise modern technology as constituting a system of domination itself, one which interlinks and interacts with the economic processes of capitalism to create a new social form, a ‘megamachine’ which integrates not only capitalism and technology, but also State, bureaucracy and military. For the FE, technology and capital, although not identical, are more similar than different, and cannot be separated into an ‘evil’ capitalism and an essentially neutral technology. Any critique of capitalism and the State must recognise the importance of contem- porary technology and the crucial role it plays in the development of new forms of domination, oppression and exploitation. Concepts of ‘capital’ and ‘mega- machine’ are also explored later in this chapter. The Fifth Estate The FE began in Detroit in 1965, started by seventeen-year-old high-school student Harvey Ovshinsky. -

The Concept of Solidarity in Anarchist Thought

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Loughborough University Institutional Repository The Concept of Solidarity in Anarchist Thought by John Nightingale A Doctoral Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of Doctor of Philosophy Loughborough University September 2015 © John Nightingale 2015 Abstract This thesis makes an original contribution to knowledge by presenting an analysis of anarchist conceptions of solidarity. Whilst recent academic literature has conceptualised solidarity from a range of perspectives, anarchist interpretations have largely been marginalised or ignored. This neglect is unjustified, for thinkers of the anarchist tradition have often emphasised solidarity as a key principle, and have offered original and instructive accounts of this important but contested political concept. In a global era which has seen the role of the nation state significantly reduced, anarchism, which consists in a fundamental critique and rejection of hierarchical state-like institutions, can provide a rich source of theory on the meaning and significance of solidarity. The work consists in detailed analyses of the concepts of solidarity of four prominent anarchist thinkers: Michael Bakunin, Peter Kropotkin, Murray Bookchin and Noam Chomsky. The analytic investigation is led by Michael Freeden’s methodology of ‘ideological morphology’, whereby ideologies are viewed as peculiar configurations of political concepts, which are themselves constituted by sub-conceptual idea- components. Working within this framework, the analysis seeks to ascertain the way in which each thinker attaches particular meanings to the concept of solidarity, and to locate solidarity within their wider ideological system. Subsequently, the thesis offers a representative profile of an ‘anarchist concept’ of solidarity, which is characterised by notions of universal inclusion, collective responsibility and the social production of individuality. -

An Unsuitable Theorist? Murray Bookchin and the PKK

Turkish Studies ISSN: 1468-3849 (Print) 1743-9663 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/ftur20 An unsuitable theorist? Murray Bookchin and the PKK Umair Muhammad To cite this article: Umair Muhammad (2018) An unsuitable theorist? Murray Bookchin and the PKK, Turkish Studies, 19:5, 799-817, DOI: 10.1080/14683849.2018.1480370 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/14683849.2018.1480370 Published online: 02 Jun 2018. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 354 View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=ftur20 TURKISH STUDIES 2018, VOL. 19, NO. 5, 799–817 https://doi.org/10.1080/14683849.2018.1480370 An unsuitable theorist? Murray Bookchin and the PKK Umair Muhammad Department of Political Science, York University, Toronto, Canada ABSTRACT Over the course of the last decade and a half the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) has transformed its ideological orientation in accord with the changing outlook of its imprisoned leader, Abdullah Öcalan. It has discarded its erstwhile Marxist- Leninist ideology for the anarchist-inspired thought of the American political theorist Murray Bookchin. Yet, the PKK’s new theorist of choice may not be an entirely suitable one. Bookchin was a rabid anti-nationalist, and this paper argues that, even after having appropriated Bookchin, the PKK has been unable to chart a non-nationalist course. Scholars of the Kurdish question have so far let Bookchin’s seeming unsuitability go unnoticed. This is likely because Bookchin’s thought is not well known. This paper offers an overview of Bookchin’s thought, and in doing so, hopefully contributes to making Bookchin better understood.