Murray Bookchin´S Libertarian Municipalism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reassembling the Anarchist Critique of Technology Zachary M

Potential, Power and Enduring Problems: Reassembling the Anarchist Critique of Technology Zachary M. Loeb* Abstract Within anarchist thought there is a current that treats a critique of technology as a central component of a broader critique of society and modernity. This tendency – which can be traced through the works of Peter Kropotkin, Rudolf Rocker, and Murray Bookchin – treats technologies as being thoroughly nested within sets of powerful social relations. Thus, it is not that technology cannot provide ‘plenty for all’ but that technology is bound up in a system where priorities other than providing plenty win out. This paper will work to reassemble the framework of this current in order to demonstrate the continuing strength of this critique. I. Faith in technological progress has provided a powerful well of optimism from which ideologies as disparate as Marxism and neoliberal capitalism have continually drawn. Indeed, the variety of machines and techniques that are grouped together under the heading “technology” often come to symbolize the tools, both * Zachary Loeb is a writer, activist, librarian, and terrible accordion player. He earned his MSIS from the University of Texas at Austin, and is currently working towards an MA in the Media, Culture, and Communications department at NYU. His research areas include the critique of technology, media refusal and resistance to technology, ethical implications of technology, as well as the intersection of library science with the STS field. 87 literally and figuratively, which a society uses to construct a modern, better, world. That technologically enhanced modern societies remain rife with inequity and oppression, while leaving a trail of toxic e-waste in their wake, is treated as an acceptable tradeoff for progress – while assurances are given that technological solutions will soon appear to solve the aforementioned troubles. -

In Pursuit of Freedom, Justice, Dignity, and Democracy

In pursuit of freedom, justice, dignity, and democracy Rojava’s social contract Institutional development in (post) – conflict societies “In establishing this Charter, we declare a political system and civil administration founded upon a social contract that reconciles the rich mosaic of Syria through a transitional phase from dictatorship, civil war and destruction, to a new democratic society where civil life and social justice are preserved”. Wageningen University Social Sciences Group MSc Thesis Sociology of Development and Change Menno Molenveld (880211578090) Supervisor: Dr. Ir. J.P Jongerden Co – Supervisor: Dr. Lotje de Vries 1 | “In pursuit of freedom, justice, dignity, and democracy” – Rojava’s social contract Abstract: Societies recovering from Civil War often re-experience violent conflict within a decade. (1) This thesis provides a taxonomy of the different theories that make a claim on why this happens. (2) These theories provide policy instruments to reduce the risk of recurrence, and I asses under what circumstances they can best be implemented. (3) I zoom in on one policy instrument by doing a case study on institutional development in the north of Syria, where governance has been set – up using a social contract. After discussing social contract theory, text analysis and in depth interviews are used to understand the dynamics of (post) conflict governance in the northern parts of Syria. I describe the functioning of several institutions that have been set –up using a social contract and relate it to “the policy instruments” that can be used to mitigate the risk of conflict recurrence. I conclude that (A) different levels of analysis are needed to understand the dynamics in (the north) of Syria and (B) that the social contract provides mechanisms to prevent further conflict and (C) that in terms of assistance the “quality of life instrument” is best suitable for Rojava. -

Social Ecology and Communalism

Murray Bookchin Bookchin Murray $ 12,95 / £ xx,xx Social Ecology and Communalism Replace this text Murray Bookchin ocial cology Social Ecology and Communalism and Communalism Social Ecology S E and Communalism AK Press Social Ecology and Communalism Murray Bookchin Social Ecology and Communalism Bookchin, Murray Social Ecology and Communalism Library of Congress Control Number 2006933557 ISBN 978-1-904859-49-9 Published by AK Press © Eirik Eiglad and Murray Bookchin 2006 AK Press 674–A 23rd St. Oakland, CA 94612 USA www.akpress.org [email protected] AK Press UK PO Box 12766 Edinburgh, EH8 9YE Scotland (0131) 555–5165 www.akuk.com [email protected] Design and layout by Eirik Eiglad Contents An Introduction to Social Ecology and Communalism 7 What is Social Ecology? 19 Radical Politics in an Era of Advanced Capitalism 53 The Role of Social Ecology in a Period of Reaction 68 The Communalist Project 77 After Murray Bookchin 117 An Introduction to Social Ecology and Communalism We are standing at a crucial crossroads. Not only does the age- old “social question” concerning the exploitation of human labor remain unresolved, but the plundering of natural resources has reached a point where humanity is also forced to politically deal with an “ecological question.” Today, we have to make conscious choices about what direction society should take, to properly meet these challenges. At the same time, we see that our very ability to make the necessary choices are being undermined by an incessant centralization of economic and political power. Not only is there a process of centralization in most modern nation states that divests humanity of any control over social affairs, but power is also gradually being transferred to transnational institutions. -

Social Ecology and the Non-Western World

Speech delivered at the conference “Challenging Capitalist Modernity II: Dissecting Capitalist Modernity–Building Democratic Confederalism”, 3–5 April 2015, Hamburg. Texts of the conference are published at http://networkaq.net/2015/speeches 2.5 Federico Venturini Social Ecology and the non-Western World Murray Bookchin was the founder of the social ecology, a philosophical perspective whose political project is called libertarian municipalism or Communalism. Recently there has been a revival of interest in this project, due to its influence on the socio-political organization in Rojava, a Kurdish self-managed region in the Syrian state. This should not be a surprise because Bookchin's works influenced Abdul Öcalan for a more than a decade, a key Kurdish leader who developed a political project called Democratic Confederalism. We should all welcome this renewed interest in social ecology and take lessons from the Rojava experience. Bookchin's analyses have always been more focussed on North-American or European experiences and so libertarian municipalism draws from these traditions. Moreover, Bookchin, who was writing in a Cold war scenario, was suspicious of the limits of national movements struggling for independence. The aim of this paper is to develop and enlarge Bookchin's analysis, including experiences and traditions from different cultures and movements, and their interrelations on a global scale. First, it explores social ecology perspective in non- Western contexts. Second, it will introduce new tools to deal with inter-national relations based on world system theory. Third, it will suggests that new experiences coming from non-Western regions can strength social ecology understanding and practices. -

Bookchin's Libertarian Municipalism

BOOKCHIN’S LIBERTARIAN MUNICIPALISM Janet BIEHL1 ABSTRACT: The purpose of this article is to present the Libertarian Municipalism Theory developed by Murray Bookchin. The text is divided into two sections. The first section presents the main precepts of Libertarian Municipalism. The second section shows how Bookchin’s ideas reached Rojava in Syria and is influencing the political organization of the region by the Kurds. The article used the descriptive methodology and was based on the works of Murray Bookchin and field research conducted by the author over the years. KEYWORDS: Murray Bookchin. Libertarian Municipalism. Rojava. Introduction The lifelong project of the American social theorist Murray Bookchin (1921-2006) was to try to perpetuate the centuries-old revolutionary socialist tradition. Born to socialist revolutionary parents in the Bronx, New York, he joined the international Communist movement as a Young Pioneer in 1930 and trained to become a young commissar for the coming proletarian revolution. Impatient with traditional secondary education, he received a thoroughgoing education in Marxism-Leninism at the Workers School in lower Manhattan, immersing himself in dialectical materialism and the labor theory of value. But by the time Stalin’s Soviet Union formed a pact with Nazi Germany (in the sum- mer of 1939), he cut his ties with the party to join the Trotskyists, who expected World War II to end in international proletarian revolutions. When the war 1 Janet Biehl is an American political writer who is the author of numerous books and articles associated with social ecology, the body of ideas developed and publicized by Murray Bookchin. -

Leaving the Left Behind 115 Post-Left Anarchy?

Anarchy after Leftism 5 Preface . 7 Introduction . 11 Chapter 1: Murray Bookchin, Grumpy Old Man . 15 Chapter 2: What is Individualist Anarchism? . 25 Chapter 3: Lifestyle Anarchism . 37 Chapter 4: On Organization . 43 Chapter 5: Murray Bookchin, Municipal Statist . 53 Chapter 6: Reason and Revolution . 61 Chapter 7: In Search of the Primitivists Part I: Pristine Angles . 71 Chapter 8: In Search of the Primitivists Part II: Primitive Affluence . 83 Chapter 9: From Primitive Affluence to Labor-Enslaving Technology . 89 Chapter 10: Shut Up, Marxist! . 95 Chapter 11: Anarchy after Leftism . 97 References . 105 Post-Left Anarchy: Leaving the Left Behind 115 Prologue to Post-Left Anarchy . 117 Introduction . 118 Leftists in the Anarchist Milieu . 120 Recuperation and the Left-Wing of Capital . 121 Anarchy as a Theory & Critique of Organization . 122 Anarchy as a Theory & Critique of Ideology . 125 Neither God, nor Master, nor Moral Order: Anarchy as Critique of Morality and Moralism . 126 Post-Left Anarchy: Neither Left, nor Right, but Autonomous . 128 Post-Left Anarchy? 131 Leftism 101 137 What is Leftism? . 139 Moderate, Radical, and Extreme Leftism . 140 Tactics and strategies . 140 Relationship to capitalists . 140 The role of the State . 141 The role of the individual . 142 A Generic Leftism? . 142 Are All Forms of Anarchism Leftism . 143 1 Anarchists, Don’t let the Left(overs) Ruin your Appetite 147 Introduction . 149 Anarchists and the International Labor Movement, Part I . 149 Interlude: Anarchists in the Mexican and Russian Revolutions . 151 Anarchists in the International Labor Movement, Part II . 154 Spain . 154 The Left . 155 The ’60s and ’70s . -

Anarchism and Environmental Philosophy

CHAPTER 13 Anarchism and Environmental Philosophy Brian Morris Introduction This chapter explores the connection between anarchism and environmental philosophy with foremost attention on the pioneer ecologist Murray Bookchin and his relation to the prominent stream of environmental thought known as deep ecology. The first section takes aim at conventional accounts of the origins of modern ecological thinking and the concomintant rise of the global environmental movement. According to such accounts, Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring (1962)—an eye-opening study of the adverse social and ecological ef- fects of synthetic pesticides—laid the foundation for the emergence of an eco- logical movement in the 1970s.1 This was accompanied, it is further alleged, by the development of an “ecological worldview” founded on a robust critique of Cartesian metaphysics and articulated in the seminal writings of system theo- rists, deep ecologists, and eco-feminists. All of this, as I will argue, is quite mis- taken. A critique of Cartesian mechanistic philosophy, along with its dualistic metaphysics and its anthropocentric ethos, already existed in the early nine- teenth century. Darwin’s evolutionary naturalism, in particular, completely un- dermined the Newtonian Cartesian mechanistic framework, replacing it with an ecological worldview that transcended both mechanistic materialism as well as all forms of religious mysticism. In combining the ecological sensibility of evolutionary naturalism with anarchism as an emerging political tradition, nineteenth-century anarchists such as Peter Kropotkin and Éliseé Reclus dis- tinguished themselves as pioneering environmental thinkers nearly a century before Rachel Carson and Arne Naess appeared on the scene. In the second section I discuss the life and work of Murray Bookchin, fo- cusing specifically on his philosophy of social ecology and dialectical natural- ism. -

Nationbuilding in Rojava

СТАТЬИ, ИССЛЕДОВАНИЯ, РАЗРАБОТКИ Кризисы и конфликты на Ближнем и Среднем Востоке M.J.Moberg NATION-BUILDING IN ROJAVA: PARTICIPATORY DEMOCRACY AMIDST THE SYRIAN CIVL WAR Название Национальное строительство в Роджаве: демократия участия в условиях на рус. яз. гражданской войны в Сирии Ключевые Сирия, гражданская война, сирийские курды, Роджава, демократический конфе- слова: дерализм Аннотация: В условиях гражданской войны в Сирии местные курды успешно использовали ослабление центральной власти для того, чтобы построить собственную систему самоуправления, известную как Роджава. Несмотря на то, что курдские силы на севере Сирии с энтузиазмом продвигают антинационалистическую программу левого толка, они сами при этом находятся в процессе национального строительства. Их главный идеологический принцип демократического конфедерализма объединяет элементы гражданского национализма и революционного социализма с целью создания новой нации в Сирии, построенной на эгалитарных началах. Политическая система Роджавы основана на принципах демократии участия (партиципаторной демократии) и федерализма, позволяющих неоднородному населению ее кантонов участвовать в самоуправлении на уровнях от локального до квазигосударственного. Хотя вопрос о признании Роджавы в ходе мирного процесса под эгидой ООН и политического урегулирования в Сирии остается открытым, практикуемый ей демократический конфедерализм может уже служить моделью инклюзивной партиципаторной демократии. Keywords: Syria, civil war, Syrian Kurds, Rojava, democratic confederalism Abstract: During -

Social Ecology and Democratic Confederalism-Eng

1 www.makerojavagreenagain.org facebook.com/GreenRojava twitter.com/GreenRojava [email protected] July 2020 Table of Contents 1 Abdullah Öcalan on the return to social ecology 6 Abdullah Öcalan 2 What is social ecology? 9 Murray Bookchin 3 The death of Nature 28 Carolyn Merchant 4 Ecology in Democratic Confederalism 33 Ercan Ayboga 5 Reber Apo is a Permaculturalist - Permaculture and 55 Political Transformation in North East Syria Viyan Qerecox 6 Ecological Catastrophe: Nature Talks Back 59 Pelşîn Tolhildan 7 Against Green Capitalism 67 Hêlîn Asî 8 The New Paradigm: Weaving ecology, democracy and gender liberation into a revolutionary political 70 paradigm Viyan Querecox 1 Abdullah Öcalan on the return to social ecology By Abdullah Öcalan Humans gain in value when they understand that animals and plants are only entrusted to them. A social 'consciousness' that lacks ecological consciousness will inevitably corrupt and disintegrate. Just as the system has led the social crisis into chaos, so has the environment begun to send out S.O.S. signals in the form of life-threatening catastrophes. Cancer-like cities, polluted air, the perforated ozone layer, the rapidly accelerating extinction of animal and plant species, the destruction of forests, the pollution of water by waste, piling up mountains of rubbish and unnatural population growth have driven the environment into chaos and insurrection. It's all about maximum profit, regardless of how many cities, people, factories, transportation, synthetic materials, polluted air and water our planet can handle. This negative development is not fate. It is the result of an unbalanced use of science and technology in the hands of power. -

Year 8 Winning Essays for Website

The Very Important Virtue of Tolerance Christian Torsell University of Notre Dame Introduction The central task of moral philosophy is to find out what it is, at the deepest level of reality, that makes right acts right and good things good. Or, at least, someone might understandably think that after surveying what some of the discipline’s most famous practitioners have had to say about it. As it is often taught, ethics proceeds in the shadows of three towering figures: Aristotle, Kant, and Mill. According to this story, the Big Three theories developed by these Big Three men— virtue ethics, deontology, and utilitarianism—divide the terrain of moral philosophy into three big regions. Though each of these regions is very different from the others in important ways, we might say that, because of a common goal they share, they all belong to the same country. Each of these theories aims to provide an ultimate criterion by which we can Judge the rightness or wrongness of acts or the goodness or badness of agents. Although the distinct criteria they offer pick out very different features of acts (and agents) as relevant in making true Judgments concerning rightness and moral value, they each claim to have identified a standard under which all such judgments are properly united. Adam Smith’s project in The Theory of Moral Sentiments1 (TMS) belongs to a different country entirely. Smith’s moral theory does not aim to give an account of the metaphysical grounding of moral properties—that is, to describe the features in virtue of which right actions and 1 All in-text citations without a listed author refer to this work, Smith (2004). -

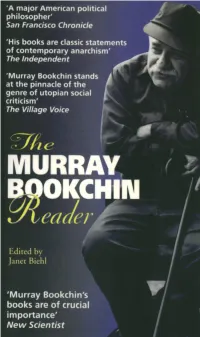

The Murray Bookchin Reader

The Murray Bookchin Reader We must always be on a quest for the new, for the potentialities that ripen with the development of the world and the new visions that unfold with them. An outlook that ceases to look for what is new and potential in the name of "realism" has already lost contact with the present, for the present is always conditioned by the future. True development is cumulative, not sequential; it is growth, not succession. The new always embodies the present and past, but it does so in new ways and more adequately as the parts of a greater whole. Murray Bookchin, "On Spontaneity and Organization," 1971 The Murray Bookchin Reader Edited by Janet Biehl BLACK ROSE BOOKS Montreal/New York London Copyright © 1999 BLACK ROSE BOOKS No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form, by any means electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system-without written permission from the publisher, or, in the case of photocopying or other reprographic copying, a license from the Canadian Reprography Collective, with the exception of brief passages quoted by a reviewer in a newspaper or magazine. Black Rose Books No. BB268 Hardcover ISBN: 1-55164-119-4 (bound) Paperback ISBN: 1-55164-118-6 (pbk.) Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 98-71026 Canadian Cataloguing in Publication Data Bookchin, Murray, 1921- Murray Bookchin reader Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 1-55164-119-4 (bound). ISBN 1-55164-118-6 (pbk.) 1. Libertarianism. 2. Environmentalism. 3. Human ecology. -

SOCIAL ANARCHISM OR LIFESTYLE ANARCHISM Murray 'Bookchin

SOCIAL ANARCHISM OR LIFESTYLE ANARCHISM AN UNB.RIDGEABLE CHASM Murray 'Bookchin AK PRESS © Copyright: 1995 Murray Bookchin Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Bookchin,Murray, 1921- Social anarchism or lifestyle anarchism : the unbridgeable chasm / byMurray Bookchin. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 1-873176-83-X (pbk.) 1. Anarchism. 2. Social problems. 3. Individualism. 4. Personalism. HX833.B635 1995 320.5'7-dc20 95-41903 CIP British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this title is available fromthe British Library . First published in 1995 by AK Press AK Press 22 Lutton Place P.O. Box 40682 Edinburgh, Scotland San Francisco, CA EH8 9PE 94140-0682 The publication of this volume was in part made possible by the generosity of Stefan Andreas Store, Chris Atton, Andy Hibbs, Stephen JohnAd ams, and the Friends of AK Press. Typeset and design donated by Freddie Baer. CONTENTS A Short Note to the Reader .......................................................... 1 Social Anarchism or Lifestyle Anarchism ................................. 4 The Left That Was: A Personal Reflection................................... ............................... 66 A NOTE TO THE READER This short work was written to deal with the fact that anarchism stands at a turning point in its long and turbulent history. At a time when popular distrust of the state has reached extraordinary proportions in many countries; when thedivision of society among a handful of opulently wealthy individuals and corporations contrasts sharply with the growing impover ishment of millions of people on a scale unprecedentedsince the Great Depression decade; when the intensity of exploitation has forced people in growing numbers to accept a work week of a length typical of the last century - anarchists have formed neither a coherent program nor a revolutionary organizationto provide a direction for the mass discontent that contemporary society is creating.