An Unsuitable Theorist? Murray Bookchin and the PKK

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reassembling the Anarchist Critique of Technology Zachary M

Potential, Power and Enduring Problems: Reassembling the Anarchist Critique of Technology Zachary M. Loeb* Abstract Within anarchist thought there is a current that treats a critique of technology as a central component of a broader critique of society and modernity. This tendency – which can be traced through the works of Peter Kropotkin, Rudolf Rocker, and Murray Bookchin – treats technologies as being thoroughly nested within sets of powerful social relations. Thus, it is not that technology cannot provide ‘plenty for all’ but that technology is bound up in a system where priorities other than providing plenty win out. This paper will work to reassemble the framework of this current in order to demonstrate the continuing strength of this critique. I. Faith in technological progress has provided a powerful well of optimism from which ideologies as disparate as Marxism and neoliberal capitalism have continually drawn. Indeed, the variety of machines and techniques that are grouped together under the heading “technology” often come to symbolize the tools, both * Zachary Loeb is a writer, activist, librarian, and terrible accordion player. He earned his MSIS from the University of Texas at Austin, and is currently working towards an MA in the Media, Culture, and Communications department at NYU. His research areas include the critique of technology, media refusal and resistance to technology, ethical implications of technology, as well as the intersection of library science with the STS field. 87 literally and figuratively, which a society uses to construct a modern, better, world. That technologically enhanced modern societies remain rife with inequity and oppression, while leaving a trail of toxic e-waste in their wake, is treated as an acceptable tradeoff for progress – while assurances are given that technological solutions will soon appear to solve the aforementioned troubles. -

Murray Bookchin´S Libertarian Municipalism

CONCEPTOS Y FENÓMENOS FUNDAMENTALES DE NUESTRO TIEMPO UNAM UNIVERSIDAD NACIONAL AUTÓNOMA DE MÉXICO INSTITUTO DE INVESTIGACIONES SOCIALES MURRAY BOOKCHIN´S LIBERTARIAN MUNICIPALISM JANET BIEHL AGOSTO 2019 1 MURRAY BOOKCHIN’S LIBERTARIAN MUNICIPALISM By Janet Biehl The lifelong project of the American social theorist Murray Bookchin (1921–2006) was to try to perpetuate the centuries-old revolutionary socialist tradition. Born to socialist revolutionary parents in the Bronx, New York, he joined the international Communist movement as a Young Pioneer in 1930, then was inducted into the Young Communist League in 1934, where he trained to become a young commissar for the coming proletarian revolution. Impatient with traditional secondary education, he received a thoroughgoing education in Marxism-Leninism at the Workers School in lower Manhattan, where he immersed himself in dialectical materialism and the labor theory of value. But in the summer of 1939, when Stalin’s Soviet Union formed a pact with Nazi Germany, he cut his ties with the party to join the Trotskyists, who expected World War II to end in international proletarian revolution. When the war ended with no such revolution, many radical socialists of his generation abandoned the Left altogether.1 But Bookchin refused to give up on the socialist revolutionary project, or abandon the goal of replacing barbarism with socialism. Instead, in the 1950s, he set out to renovate leftist thought for the current era. He concluded that the new revolutionary arena would be not the factory but the city; that the new revolutionary agent would be not the industrial worker but the citizen; that the basic institution of the new society must be, not the dictatorship of the proletariat, but the citizens’ assembly in a face-to-face democracy; and that the limits of capitalism must be ecological. -

Social Ecology and Communalism

Murray Bookchin Bookchin Murray $ 12,95 / £ xx,xx Social Ecology and Communalism Replace this text Murray Bookchin ocial cology Social Ecology and Communalism and Communalism Social Ecology S E and Communalism AK Press Social Ecology and Communalism Murray Bookchin Social Ecology and Communalism Bookchin, Murray Social Ecology and Communalism Library of Congress Control Number 2006933557 ISBN 978-1-904859-49-9 Published by AK Press © Eirik Eiglad and Murray Bookchin 2006 AK Press 674–A 23rd St. Oakland, CA 94612 USA www.akpress.org [email protected] AK Press UK PO Box 12766 Edinburgh, EH8 9YE Scotland (0131) 555–5165 www.akuk.com [email protected] Design and layout by Eirik Eiglad Contents An Introduction to Social Ecology and Communalism 7 What is Social Ecology? 19 Radical Politics in an Era of Advanced Capitalism 53 The Role of Social Ecology in a Period of Reaction 68 The Communalist Project 77 After Murray Bookchin 117 An Introduction to Social Ecology and Communalism We are standing at a crucial crossroads. Not only does the age- old “social question” concerning the exploitation of human labor remain unresolved, but the plundering of natural resources has reached a point where humanity is also forced to politically deal with an “ecological question.” Today, we have to make conscious choices about what direction society should take, to properly meet these challenges. At the same time, we see that our very ability to make the necessary choices are being undermined by an incessant centralization of economic and political power. Not only is there a process of centralization in most modern nation states that divests humanity of any control over social affairs, but power is also gradually being transferred to transnational institutions. -

Bookchin's Libertarian Municipalism

BOOKCHIN’S LIBERTARIAN MUNICIPALISM Janet BIEHL1 ABSTRACT: The purpose of this article is to present the Libertarian Municipalism Theory developed by Murray Bookchin. The text is divided into two sections. The first section presents the main precepts of Libertarian Municipalism. The second section shows how Bookchin’s ideas reached Rojava in Syria and is influencing the political organization of the region by the Kurds. The article used the descriptive methodology and was based on the works of Murray Bookchin and field research conducted by the author over the years. KEYWORDS: Murray Bookchin. Libertarian Municipalism. Rojava. Introduction The lifelong project of the American social theorist Murray Bookchin (1921-2006) was to try to perpetuate the centuries-old revolutionary socialist tradition. Born to socialist revolutionary parents in the Bronx, New York, he joined the international Communist movement as a Young Pioneer in 1930 and trained to become a young commissar for the coming proletarian revolution. Impatient with traditional secondary education, he received a thoroughgoing education in Marxism-Leninism at the Workers School in lower Manhattan, immersing himself in dialectical materialism and the labor theory of value. But by the time Stalin’s Soviet Union formed a pact with Nazi Germany (in the sum- mer of 1939), he cut his ties with the party to join the Trotskyists, who expected World War II to end in international proletarian revolutions. When the war 1 Janet Biehl is an American political writer who is the author of numerous books and articles associated with social ecology, the body of ideas developed and publicized by Murray Bookchin. -

Leaving the Left Behind 115 Post-Left Anarchy?

Anarchy after Leftism 5 Preface . 7 Introduction . 11 Chapter 1: Murray Bookchin, Grumpy Old Man . 15 Chapter 2: What is Individualist Anarchism? . 25 Chapter 3: Lifestyle Anarchism . 37 Chapter 4: On Organization . 43 Chapter 5: Murray Bookchin, Municipal Statist . 53 Chapter 6: Reason and Revolution . 61 Chapter 7: In Search of the Primitivists Part I: Pristine Angles . 71 Chapter 8: In Search of the Primitivists Part II: Primitive Affluence . 83 Chapter 9: From Primitive Affluence to Labor-Enslaving Technology . 89 Chapter 10: Shut Up, Marxist! . 95 Chapter 11: Anarchy after Leftism . 97 References . 105 Post-Left Anarchy: Leaving the Left Behind 115 Prologue to Post-Left Anarchy . 117 Introduction . 118 Leftists in the Anarchist Milieu . 120 Recuperation and the Left-Wing of Capital . 121 Anarchy as a Theory & Critique of Organization . 122 Anarchy as a Theory & Critique of Ideology . 125 Neither God, nor Master, nor Moral Order: Anarchy as Critique of Morality and Moralism . 126 Post-Left Anarchy: Neither Left, nor Right, but Autonomous . 128 Post-Left Anarchy? 131 Leftism 101 137 What is Leftism? . 139 Moderate, Radical, and Extreme Leftism . 140 Tactics and strategies . 140 Relationship to capitalists . 140 The role of the State . 141 The role of the individual . 142 A Generic Leftism? . 142 Are All Forms of Anarchism Leftism . 143 1 Anarchists, Don’t let the Left(overs) Ruin your Appetite 147 Introduction . 149 Anarchists and the International Labor Movement, Part I . 149 Interlude: Anarchists in the Mexican and Russian Revolutions . 151 Anarchists in the International Labor Movement, Part II . 154 Spain . 154 The Left . 155 The ’60s and ’70s . -

Anarchism and Environmental Philosophy

CHAPTER 13 Anarchism and Environmental Philosophy Brian Morris Introduction This chapter explores the connection between anarchism and environmental philosophy with foremost attention on the pioneer ecologist Murray Bookchin and his relation to the prominent stream of environmental thought known as deep ecology. The first section takes aim at conventional accounts of the origins of modern ecological thinking and the concomintant rise of the global environmental movement. According to such accounts, Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring (1962)—an eye-opening study of the adverse social and ecological ef- fects of synthetic pesticides—laid the foundation for the emergence of an eco- logical movement in the 1970s.1 This was accompanied, it is further alleged, by the development of an “ecological worldview” founded on a robust critique of Cartesian metaphysics and articulated in the seminal writings of system theo- rists, deep ecologists, and eco-feminists. All of this, as I will argue, is quite mis- taken. A critique of Cartesian mechanistic philosophy, along with its dualistic metaphysics and its anthropocentric ethos, already existed in the early nine- teenth century. Darwin’s evolutionary naturalism, in particular, completely un- dermined the Newtonian Cartesian mechanistic framework, replacing it with an ecological worldview that transcended both mechanistic materialism as well as all forms of religious mysticism. In combining the ecological sensibility of evolutionary naturalism with anarchism as an emerging political tradition, nineteenth-century anarchists such as Peter Kropotkin and Éliseé Reclus dis- tinguished themselves as pioneering environmental thinkers nearly a century before Rachel Carson and Arne Naess appeared on the scene. In the second section I discuss the life and work of Murray Bookchin, fo- cusing specifically on his philosophy of social ecology and dialectical natural- ism. -

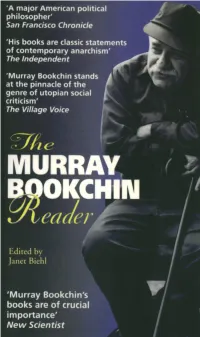

The Murray Bookchin Reader

The Murray Bookchin Reader We must always be on a quest for the new, for the potentialities that ripen with the development of the world and the new visions that unfold with them. An outlook that ceases to look for what is new and potential in the name of "realism" has already lost contact with the present, for the present is always conditioned by the future. True development is cumulative, not sequential; it is growth, not succession. The new always embodies the present and past, but it does so in new ways and more adequately as the parts of a greater whole. Murray Bookchin, "On Spontaneity and Organization," 1971 The Murray Bookchin Reader Edited by Janet Biehl BLACK ROSE BOOKS Montreal/New York London Copyright © 1999 BLACK ROSE BOOKS No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form, by any means electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system-without written permission from the publisher, or, in the case of photocopying or other reprographic copying, a license from the Canadian Reprography Collective, with the exception of brief passages quoted by a reviewer in a newspaper or magazine. Black Rose Books No. BB268 Hardcover ISBN: 1-55164-119-4 (bound) Paperback ISBN: 1-55164-118-6 (pbk.) Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 98-71026 Canadian Cataloguing in Publication Data Bookchin, Murray, 1921- Murray Bookchin reader Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 1-55164-119-4 (bound). ISBN 1-55164-118-6 (pbk.) 1. Libertarianism. 2. Environmentalism. 3. Human ecology. -

SOCIAL ANARCHISM OR LIFESTYLE ANARCHISM Murray 'Bookchin

SOCIAL ANARCHISM OR LIFESTYLE ANARCHISM AN UNB.RIDGEABLE CHASM Murray 'Bookchin AK PRESS © Copyright: 1995 Murray Bookchin Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Bookchin,Murray, 1921- Social anarchism or lifestyle anarchism : the unbridgeable chasm / byMurray Bookchin. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 1-873176-83-X (pbk.) 1. Anarchism. 2. Social problems. 3. Individualism. 4. Personalism. HX833.B635 1995 320.5'7-dc20 95-41903 CIP British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this title is available fromthe British Library . First published in 1995 by AK Press AK Press 22 Lutton Place P.O. Box 40682 Edinburgh, Scotland San Francisco, CA EH8 9PE 94140-0682 The publication of this volume was in part made possible by the generosity of Stefan Andreas Store, Chris Atton, Andy Hibbs, Stephen JohnAd ams, and the Friends of AK Press. Typeset and design donated by Freddie Baer. CONTENTS A Short Note to the Reader .......................................................... 1 Social Anarchism or Lifestyle Anarchism ................................. 4 The Left That Was: A Personal Reflection................................... ............................... 66 A NOTE TO THE READER This short work was written to deal with the fact that anarchism stands at a turning point in its long and turbulent history. At a time when popular distrust of the state has reached extraordinary proportions in many countries; when thedivision of society among a handful of opulently wealthy individuals and corporations contrasts sharply with the growing impover ishment of millions of people on a scale unprecedentedsince the Great Depression decade; when the intensity of exploitation has forced people in growing numbers to accept a work week of a length typical of the last century - anarchists have formed neither a coherent program nor a revolutionary organizationto provide a direction for the mass discontent that contemporary society is creating. -

The Concept of Solidarity in Anarchist Thought

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Loughborough University Institutional Repository The Concept of Solidarity in Anarchist Thought by John Nightingale A Doctoral Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of Doctor of Philosophy Loughborough University September 2015 © John Nightingale 2015 Abstract This thesis makes an original contribution to knowledge by presenting an analysis of anarchist conceptions of solidarity. Whilst recent academic literature has conceptualised solidarity from a range of perspectives, anarchist interpretations have largely been marginalised or ignored. This neglect is unjustified, for thinkers of the anarchist tradition have often emphasised solidarity as a key principle, and have offered original and instructive accounts of this important but contested political concept. In a global era which has seen the role of the nation state significantly reduced, anarchism, which consists in a fundamental critique and rejection of hierarchical state-like institutions, can provide a rich source of theory on the meaning and significance of solidarity. The work consists in detailed analyses of the concepts of solidarity of four prominent anarchist thinkers: Michael Bakunin, Peter Kropotkin, Murray Bookchin and Noam Chomsky. The analytic investigation is led by Michael Freeden’s methodology of ‘ideological morphology’, whereby ideologies are viewed as peculiar configurations of political concepts, which are themselves constituted by sub-conceptual idea- components. Working within this framework, the analysis seeks to ascertain the way in which each thinker attaches particular meanings to the concept of solidarity, and to locate solidarity within their wider ideological system. Subsequently, the thesis offers a representative profile of an ‘anarchist concept’ of solidarity, which is characterised by notions of universal inclusion, collective responsibility and the social production of individuality. -

Changing Anarchism.Pdf

Changing anarchism Changing anarchism Anarchist theory and practice in a global age edited by Jonathan Purkis and James Bowen Manchester University Press Manchester and New York distributed exclusively in the USA by Palgrave Copyright © Manchester University Press 2004 While copyright in the volume as a whole is vested in Manchester University Press, copyright in individual chapters belongs to their respective authors. This electronic version has been made freely available under a Creative Commons (CC-BY-NC- ND) licence, which permits non-commercial use, distribution and reproduction provided the author(s) and Manchester University Press are fully cited and no modifications or adaptations are made. Details of the licence can be viewed at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ Published by Manchester University Press Oxford Road, Manchester M13 9NR, UK and Room 400, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010, USA www.manchesteruniversitypress.co.uk British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data applied for ISBN 0 7190 6694 8 hardback First published 2004 13 12 11 10 09 08 07 06 05 04 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Typeset in Sabon with Gill Sans display by Servis Filmsetting Ltd, Manchester Printed in Great Britain by CPI, Bath Dedicated to the memory of John Moore, who died suddenly while this book was in production. His lively, innovative and pioneering contributions to anarchist theory and practice will be greatly missed. -

An Ungovernable Force? Food Not Bombs, Homeless Activism

AN UNGOVERNABLE FORCE? FOOD NOT BOMBS, HOMELESS ACTIVISM AND POLITICS IN SAN FRANCISCO, 1988-1995 by SEAN MICHAEL PARSON A DISSERTATION Presented to the Department ofPolitical Science and the Graduate School ofthe University ofOregon in partial fulfillment ofthe requirements for the degree of Doctor ofPhilosophy September 2010 11 University of Oregon Graduate School Confirmation of Approval and Acceptance of Dissertation prepared by: Sean Parson Title: "An Ungovernable Force? Food Not Bombs, Homeless Activism and Politics in San Francisco, 1988-1995" This dissertation has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment ofthe requirements for the degree in the Department ofPolitical Science by: Gerald Berk, Chairperson, Political Science Joseph Lowndes, Member, Political Science Deborah Baumgold, Member, Political Science Michael Dreiling, Outside Member, Sociology and Richard Linton, Vice President for Research and Graduate Studies/Dean ofthe Graduate School for the University of Oregon. September 4,2010 Original approval signatures are on file with the Graduate School and the University of Oregon Libraries. III © 2010 Sean M. Parson IV An Abstract ofthe Dissertation of Sean Michael Parson for the degree of Doctor ofPhilosophy in the Department ofPolitical Science to be taken September 2010 Title: AN UNGOVERNABLE FORCE? FOOD NOT BOMBS, HOMELESS ACTIVISM AND POLITICS IN SAN FRANCISCO, 1988-1995 Approved: ~ _ Gerald Berk This study examines the interaction between two anarchist support groups for the homeless, Food Not Bombs and Homes Not Jails, and the city ofSan Francisco between 1988 and 1995. Food Not Bombs provides free meals in public spaces and protests government and corporate policies that harm the poor and homeless. Homes Not Jails is a sister group ofFood Not Bombs that opens up unused houses and government buildings to provide housing for homeless residents. -

Anarchist Social Science : Its Origins and Development

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 1974 Anarchist social science : its origins and development. Rochelle Ann Potak University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses Potak, Rochelle Ann, "Anarchist social science : its origins and development." (1974). Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014. 2504. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses/2504 This thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ANARCHIST SOCIAL SCIENCE: ITS ORIGINS AND DEVELOPMENT A Thesis Presented By ROCHELLE ANN POTAK Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the den:ree of MASTER OF ARTS December 1974 Political Science ANARCHIST SOCIAL SCIENCE: ITS ORIGINS AND DEVELOPMENT A Thesis By ROCHELLE AliN POTAK Approved as to style and content by: Guenther Lewy, Chairman of Committee Dean Albertson, Member — Glen Gordon, Chairman Department of Political Science December 197^ Affectionately dedicated to my friends Men have sought for aees to discover the science of govern- ment; and lo l here it is, that men cease totally to attempt to govern each other at allJ that they learn to know the consequences of their OT-m acts, and that they arrange their relations with each other upon such a basis of science that the disagreeable consequences shall be assumed by the agent himself. Stephen Pearl Andrews V PREFACE The primary purpose of this thesis is to examine anarchist thought from a new perspective.