On Development of Curricula on Human Rights and Health Equity in Public Health Response

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Capturing the Demographic Dividend in Pakistan

CAPTURING THE DEMOGRAPHIC DIVIDEND IN PAKISTAN ZEBA A. SATHAR RABBI ROYAN JOHN BONGAARTS EDITORS WITH A FOREWORD BY DAVID E. BLOOM The Population Council confronts critical health and development issues—from stopping the spread of HIV to improving reproductive health and ensuring that young people lead full and productive lives. Through biomedical, social science, and public health research in 50 countries, we work with our partners to deliver solutions that lead to more effective policies, programs, and technologies that improve lives around the world. Established in 1952 and headquartered in New York, the Council is a nongovernmental, nonprofit organization governed by an international board of trustees. © 2013 The Population Council, Inc. Population Council One Dag Hammarskjold Plaza New York, NY 10017 USA Population Council House No. 7, Street No. 62 Section F-6/3 Islamabad, Pakistan http://www.popcouncil.org The United Nations Population Fund is an international development agency that promotes the right of every woman, man, and child to enjoy a life of health and equal opportunity. UNFPA supports countries in using population data for policies and programmes to reduce poverty and to ensure that every pregnancy is wanted, every birth is safe, every young person is free of HIV and AIDS, and every girl and woman is treated with dignity and respect. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Capturing the demographic dividend in Pakistan / Zeba Sathar, Rabbi Royan, John Bongaarts, editors. -- First edition. pages ; cm Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 978-0-87834-129-0 (alkaline paper) 1. Pakistan--Population--Economic aspects. 2. Demographic transition--Economic aspects--Pakistan. -

SURVEY of PAKISTAN Rawalpindi INVITATION to BID Survey Of

SURVEY OF PAKISTAN Rawalpindi INVITATION TO BID Survey of Pakistan, a National Surveying & Mapping Agency invites sealed bids under the Project titled "Cadestral Mapping” under Single Stage• Two Envelop procedure from the firms registered with Income Tax & Sales Tax Departments for followings: i) Cadestral Mapping of Karachi City Zone-A ii) Cadestral Mapping of Karachi City Zone-B iii) Cadestral Mapping of Lahore City Zone-A iv) Cadestral Mapping of Lahore City Zone-B v) Cadestral Mapping of Statelands Sindh (Division Wise) vi) Cadestral Mapping of Statelands Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (Division Wise) vii) Cadestral Mapping of Statelands Punjab (Division Wise) viii) Cadestral Mapping of Sectors in CDA Islamabad 2). For Cadastral mapping of Statelands, the bids will be submitted for each Division of Provinces separately. Firms can apply for Cadastral Mapping of Statelands in one or Division depending upon their capacity. Bidding documents, containing detailed terms and conditions, technical specifications, method of procurement, procedure for submission of bids, bid security, evaluation criteria, performance guarantee etc., are available for the interested bidders at website of Public Procurement Regulatory Authority, which can be downloaded. 3). The bids, prepared in accordance with the instructions in the bidding documents, must reach at Survey of Pakistan, Faizabad Rawalpindi duly addressed to the Chairman Purchase Committee on or before 24-02-2021 at 10:30 hrs. Bids will be opened on the same day at 11:00 hrs. This advertisement is also available on PPRA's website at www.ppra.org.pk and Survey of Pakistan website www.sop.gov.pk. (Muhammad Tanvir) Director Directorate of Photogrammetry Chairman Purchase Committee 051-9290217 SURVEY OF PAKISTAN BID SOLICITATION DOCUMENT FOR AWARD OF CONTRACT OF CADASTRAL MAPPING OF CDA Survey of Pakistan, Faizabad, Murree Road, Rawalpindi Table of Contents 1 Project Overview .............................................................................................. -

Download PDF Copy of Political Map of Pakistan 2020

TAJIKISTAN C H I N G I L A 70 J & K G Peshawar ( FINAL STATUS NOT YET ISLAMABAD DETERMINED) I T Quetta Lahore 30 - B 60 GILGIT A Karachi Tropic of Cancer L T 80 S 20 I Karakoram Pass Junagadh & U N Manavadar INDUS RIVER S R A V T T E S Y K I A A O F P A N 1767 1947 1823 W H K N U INDUS RIVER Line of Control PAKISTAN T MUZAFFARABAD H Political K SRINAGAR A INDIAN ILLEGALLY OCCUPIED JAMMU & KASHMIR PESHAWAR Scale 1: 3,000,000 N (DISPUTED TERRITORY - FINAL STATUS TO BE DECIDED IN LINE WITH RELEVANT UNSC RESOLUTIONS) ISLAMABAD A R P E B T Y * H S W K orking Boundary I JHELUM RIVER N INDUS RIVER A LAHORE The red dotted line represents approximately the line of control in Jammu & Kashmir. The state of Jammu & Kashmir and its accession H CHENAB RIVER is yet to be decided through a plebiscite under the relevant United Nations Security Council Resolutions. G Actual boundary in the area where remark FRONTIER UNDEFINED P U N J A B appears, would ultimately be decided by the sovereign authorities VI RIVER F RA concerned after the final settlement of the Jammu & Kashmir dispute. *AJ&K stands for Azad Jammu & Kashmir as defined in the AJK Interim A Constitution Act, 1974. QUETTA N CHENAB RIVER SUTLEJ RIVER A A LEGEND T I Capital of Country . ISLAMABAD S Headquarters; Province . .PESHAWAR D Boundary; International . I INDUS RIVER Boundary; Province . N Boundary; Working . P Line of Control . -

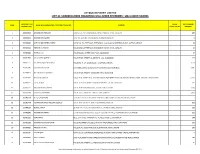

List of Unclaimed Shares and Dividend

ATTOCK REFINERY LIMITED LIST OF SHAREHOLDERS REGARDING UNCLAIMED DIVIDENDS / UNCLAIMED SHARES FOLIO NO / CDC SHARE NET DIVIDEND S/NO. NAME OF SHAREHOLDER / CERTIFICATE HOLDER ADDRESS ACCOUNT NO. CERTIFICATES AMOUNT 1 208020582 MUHAMMAD HAROON DASKBZ COLLEGE, KHAYABAN-E-RAHAT, PHASE-VI, D.H.A., KARACHI 450 2 208020632 MUHAMMAD SALEEM SHOP NO.22, RUBY CENTRE,BOULTON MARKETKARACHI 8 3 307000046 IGI FINEX SECURITIES LIMITED SUIT # 701-713, 7TH FLOOR, THE FORUM, G-20, BLOCK 9, KHAYABAN-E-JAMI, CLIFTON, KARACHI 15 4 307013023 REHMAT ALI HASNIE HOUSE # 96/2, STREET # 19, KHAYABAN-E-RAHAT, DHA-6, KARACHI. 15 5 307020846 FARRUKH ALI HOUSE # 246-A, STREET # 39, F-11/3, ISLAMABAD 67 6 307022966 SALAHUDDIN QURESHI HOUSE # 785, STREET # 11, SECTOR G-11/1, ISLAMABAD. 174 7 307025555 ALI IMRAN IQBAL MOTIWALA HOUSE NO. H-1, F-48-49, BLOCK - 4, CLIFTON, KARACHI. 2,550 8 307026496 MUHAMMAD QASIM C/O HABIB AUTOS, ADAM KHAN, PANHWAR ROAD, JACOBABAD. 2,085 9 307028922 NAEEM AHMED SIDDIQUI HOUSE # 429, STREET # 4, SECTOR # G-9/3, ISLAMABAD. 7 10 307032411 KHALID MEHMOOD HOUSE # 10 , STREET # 13 , SHAHEEN TOWN, POST OFFICE FIZAI, C/O MADINA GERNEL STORE, CHAKLALA, RAWALPINDI. 6,950 11 307034797 FAZAL AHMED HOUSE # A-121,BLOCK # 15,RAILWAY COLONY , F.B AREA, KARACHI 225 12 307037535 NASEEM AKHTAR AWAN HOUSE # 183/3 MUNIR ROAD , LAHORE CANTT LAHORE . 1,390 13 307039564 TEHSEEN UR REHMAN HOUSE # S-5, JAMI STAFE LANE # 2, DHA, KARACHI. 3,475 14 307041594 ATTIQ-UR-REHMAN C/O HAFIZ SHIFATULLAH,BADAR GENERALSTORE,SHAMA COLONY,BEGUM KOT,LAHORE 7 15 307042774 MUHAMMAD NASIR HUSSAIN SIDDIQUI HOUSE-A-659,BLOCK-H, NORTH NAZIMABAD, KARACHI. -

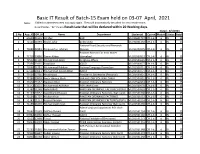

Basic IT Result of Batch-15 Exam Held on 03-07 April, 2021 Note: Failled Or Absentees Need Not Apply Again

Basic IT Result of Batch-15 Exam held on 03-07 April, 2021 Note: Failled or absentees need not apply again. They will automatically be called for next retake exam. Result Status "RL" means Result Late that will be declared within 20 Working days. Dated: 4/5/2021 S.No App_ID Off_Sr Name Department Studentid Course Module Status Batch 1 69690 21515 Ali Sher EAD VU180601737 CPL1-6 6 RL 15 2 72124 21093 Khalid Zafar policy wing VU191001292 CPL1-6 6 RL 15 National Food Security and Research 3 74699 22881 Maqsood-ur-rehman Division VU191200205 CPL1-6 6 RL 15 Pakistan Mission For Indis Water 4 71718 20880 Zamin Abbas Islamabad VU201500522 CPL1-6 6 RL 15 5 72512 21500 Muhammad Azam Religious Affairs VU201500665 CPL1-6 6 RL 15 6 75356 23135 Fazal Dad IESCO VU201500677 CPL1-6 6 RL 15 7 73560 21981 Muhammad Rukhsar National Language Promotion VU201500751 CPL1-6 6 RL 15 8 67148 20641 Muhammad Junaid Akbar Admin VU201500771 CPL1-6 6 RL 15 9 73904 22704 Khushnood President's Secretariat (Personal) VU201500829 CPL1-6 6 RL 15 10 72286 20893 Ansar Ahmed Shah SAA FACTORY POF WAH CANTT VU201500931 CPL1-6 6 RL 15 11 71610 21652 Nadeem Khan Pakistan Ordnance Factories VU201500953 CPL1-6 6 RL 15 12 71142 20525 Muhammad Asif Khan POFs Wah Cantt VU201500970 CPL1-6 6 RL 15 13 71780 21248 Nahid Bhatti PAKISTAN ORDNANCE FACTORIES (POFs) VU201500993 CPL1-6 6 RL 15 14 71197 20552 Syed Shahid Hussain Pakistan Ordnance Factories, Wah Cantt. VU201501008 CPL1-6 6 RL 15 15 72164 21707 Mohsin Khan PAKISTAN ORDNANCE FACTORIES VU201501022 CPL1-6 6 RL 15 16 71783 21251 Kousar Perveen PAKISTAN ORDNANCE FACTORIES (POFs) VU201501024 CPL1-6 6 RL 15 17 71155 21693 Muhammad Imran Pakistan Ordnance Factories Wah Cantt. -

Strategic Salience of the Gwadar Port an Analytical Study

Strategic Salience of the Gwadar Port An Analytical Study Sindhu Dinesh* Gwadar Port has gained currency in the light of recent international developments that are increasingly focused on maritime-related economic activities. It has become an important reference point for people discussing the geopolitics and geo-economics of the South Asian region. The article explores in detail the strategic salience of Gwadar against the backdrop of the ongoing Baloch insurgency, the current activities being undertaken at Gwadar, the strategic outlook of Pakistan and China on the port and the implications it holds for China–Pakistan ties. Gwadar Port holds strategic significance due to its prime location and the massive investments by China to provide world-class facilities of docking at the port. The port has increased the existing economic and strategic interdependence between China and Pakistan. INTRODUCTION The twenty-first century has been characterised by several countries refocusing to invest more and expand in the maritime domain. Presently, naval activities, especially among the developing nations, have assumed accelerated economic and political significance. In essence, ‘port’ in a country’s economy is the bridge between its land and sea economic activities. It occupies a crucial position and its utilisation influences the * The author is a Postgraduate Research Scholar from the Department of Geopolitics and International Relations, Manipal Academy of Higher Education, Manipal. She is currently working as Research Analyst at Janes Defence India. ISSN 0976-1004 print © 2021 Manohar Parrikar Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses Journal of Defence Studies, Vol. 15, No. 1, January–March 2021, pp. 53–78 54 Journal of Defence Studies pace of progress of a nation. -

The Word Gwadar Is Derived from Two Balochi Words 'Gwa' Means Wind

Grassroots, Vol.52, No.I January-June 2018 EFFECT OF CHINA–PAKISTAN ECONOMIC RELATIONS TO THE ECONOMIC GROWTH OF BALOCHISTAN: A CASE STUDY OF GWADAR PORT Mohammad Hanif Baloch Dr Imdad Ali Khowaja Dr Kamleshwer Lohana ABSTRACT The Gwadar city is located between the two most important Gulf and Persian regions of the world. Both areas are so rich in resources, simply it is said that, those regions are famous for the production of Oil and Gas. The southern border of Balochistan province is situated in the Arabian Sea. After the construction of a sea port in 2008 with the technical and financial assistance of China, the status of this thinly populated area of the city of Balochistan province has been converted into the economic corridor for suitable trading between the countries of the world. Now a days trading is possible through the sea port, where a country can earn a billion dollars, as port directly connects one area to another area of the world. This paper introduces the economic effects of trading, such as growth. It is expected that the project would generate thousands of jobs for the local people, because of the construction of new industries, agricultural development and communication facilities, which would also be of benefit to the nation as a whole change the area location. The data highlights that the trade between China and Pakistan has increased to 75.8 million USA Dollars due to the bilateral trade agreement between them after the construction of the port. While the output of industries has doubled if compared to the period between 2005 and 2009 and before it. -

Technical Report

TECHNICAL REPORT Boundary Demarcation, Surveying & Mapping of Sustainable Forest Management (SFM) areas of Afforestation Division Shaheed Benazirabad. Survey of Pakistan Directorate of Southern Circle No. 9 Survey Party Karachi Tele: 021-99266387 Fax: 021-99266382 TABLE OF CONTENTS Contents Foreword ________________________________________________________________ 1 Introduction ______________________________________________________________ 2 Objectives _______________________________________________________________ 6 Methodology______________________________________________________________ 8 Field Activities and Summary ________________________________________________ 15 Project Team ____________________________________________________________ 18 Constraints and lessons learnt _______________________________________________ 19 Recommendation and Suggestions ___________________________________________ 20 Contact Information _______________________________________________________ 21 Maps of the Forest ________________________________________________________ 22 FOREWORD Foreword It gives me immense pleasure to acknowledge that Directorate of Southern Circle, Survey of Pakistan, (SoP), Karachi have completed the boundary demarcation &Topographic survey of riverine forest of Shaheed Benazirabad Division Sustainable Forest Management (SFM) Project in compliance of Court orders and under provision of Global Environment Facility (GEF) and United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) assisted Programme. In this project physical boundaries of all -

China–Pakistan Economic Corridor, Logistics Developments and Economic Growth in Pakistan

logistics Article China–Pakistan Economic Corridor, Logistics Developments and Economic Growth in Pakistan Zunaira Khadim 1,2, Irem Batool 2,* and Muhammad Bilal Lodhi 2 1 Department of Economics, National College of Business Administration & Economics, Lahore 54660, Pakistan; [email protected] 2 Department of Management Sciences, COMSATS University Islamabad, Sahiwal Campus, Sahiwal 57000, Pakistan; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +92-347-4763300 Abstract: The study aims to analyze the impact of China–Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) logistics-related developments on economic growth in Pakistan. The study defined a Cobb–Douglas type of research framework in which the country’s real income level relates to four factor inputs, e.g., employed labor force, logistics development, financial development, and energy consumption in an economy. The study utilized the time series data set for the period 1972–2018. To estimate the long run relationship and short run adjustment mechanism, the study used Johansen’s method of co-integration and error correction model. Estimated results showed that the country’s logistics developments have a significant positive impact on economic growth in both the long run and the short run. It implies that China–Pakistan collaborative efforts for logistics developments will have a strong positive impact on economic growth in Pakistan. Keywords: China–Pakistan Economic Corridor developments; logistics developments; economic growth; Pakistan Citation: Khadim, Z.; Batool, I.; Bilal Lodhi, M. China–Pakistan Economic Corridor, Logistics Developments and Economic Growth in Pakistan. 1. Introduction Logistics 2021, 5, 35. https://doi.org/ China’s One Belt and One Road (B & R) Initiative is a giant project, under which the 10.3390/logistics5020035 Chinese government intends to reconstruct the ancient ‘Silk Road’ in a contemporary mode in the vast area extending from China to Europe [1]. -

Survey Training Institute H-8/2, Islamabad

SURVEY OF PAKISTAN SURVEY TRAINING INSTITUTE H-8/2, ISLAMABAD ADMISSION FORM For ONE YEAR CERTIFICATE COURSE IN LAND SURVEYING (Form Processing Fee Rs. 200/-) Name: Father’s Name: Date of Birth: Religion Gender: Male Female Domicile: CNIC No. Postal Address: Permanent Address: Phone No: Mobile No: QUALIFICATION Certificate Year of Board / Marks Total Main Subjects Div %age / Degree Passing University Obt. Marks SSC HSSC Bachelors Masters Any Other Previous experience (if any): Current employment (if any): Page 1 of 4 AFFIDAVIT I solemnly declare that all the entries made in this admission form are correct to the best of my knowledge and belief. During the training period, I shall abide by the rules/regulations made and notified by the Survey Training Institute from time to time. Date: Signature of Candidate: FOR OFFICE USE ONLY Entry Test Marks: Admission: Recommended Not Recommended Course No: Registration No: CHIEF INSTRUCTOR FEE STRUCTURE Admission Fee: Rs. 1000 Tuition Fee: Rs. 2000 per month Other Charges: Rs. 5500 Security Refundable: Rs. 2000 Registration and exam fee of Punjab Board of Technical Education will be collected according to board rules. Hostel Charges (Limited space available in hostel): Room Charges: Rs. 20 per day Hostel Security: Rs. 1000 (refundable) COURSE CONTENTS a. Theory CLS-101 Mathematics, Scales CLS-102 Introduction to Survey Instruments & their use, Measurement of Vertical Distances CLS-103 Surveying, Field Astronomy & Curves CLS-104 Tachometry, Plane Tabling, Map Making CLS-105 Computation, Measurement & Errors CLS-106 Photogrammetry, General Information on Surveying CLS-107 Fundamentals of Microcomputers b. Practical Leveling, Traversing, GPS, Total Station and Plane Tabling on Scale on different scale. -

SURVEY of PAKISTAN Rawalpindi

SURVEY OF PAKISTAN Rawalpindi INVITATION TO BID (For Procurement of Furniture items) Survey of Pakistan invites sealed bids under the Project titled “Cadestral Mapping” through Single Stage-Two Envelop procedure from the Original manufacturers / Authorized Distributers etc., registered with Income Tax & Sales Tax Departments for supply of furniture. 2). Bidding documents, containing detail of Furniture, terms and conditions, technical specifications, method of procurement, procedure for submission of bids, bid security, etc., are available for the interested bidders on PPRA’s website at www.ppra.org.pk and Survey of Pakistan website www.sop.gov.pk., which can be downloaded. 3). The bids, prepared in accordance with the instructions in the bidding documents, must reach at Survey of Pakistan Faizabad Rawalpindi duly addressed to the Chairman Purchase Committee on or before 10-05-2021 at 11:00 hrs. Bids will be opened on the same day at 11:30 hrs. (Muhammad Tanvir) Director Chairman Purchase Committee 051-9290217 Page 1 of 39 TERMS & CONDITIONS 1. Applications on prescribed form (attached) along with technical specifications (compliance sheet) and contract, which can be downloaded from the website of PPRA, should reach the Chairman Purchase Committee, Survey of Pakistan Faizabad Rawalpindi by registered post/courier latest by 11:00 hours on 10- 05-2021. These will be opened at 11:30 hours on the same day in the presence of bidders or their authorized representatives. 2. The method of procurement is single stage – two envelopes as per PPRA’s Rule-36(b). 3. The Bidders will send their Proposals in two sealed envelopes, marked as “FINANCIAL PROPOSAL” & “TECHNICAL PROPOSAL” in bold and legible letters to avoid confusion. -

Survey of Pakistan

SURVEY OF PAKISTAN 1. OVERVIEW. a. Introduction: Survey of Pakistan is a National Surveying and Mapping Agency and an attached department of Ministry of Defence with its headquarters at Rawalpindi and sub-offices (Circle Field Directorates) in all four provincial capitals. It emerged from Survey of India at the time of independence. b. Mission: To delineate and demarcate International borders, carry out topographic survey, prepare national geographical data base and publish maps of Pakistan. c. Role / Functions/Responsibilities: i. To delineate International borders and demarcate & relocate border pillars. ii. To carry out topographic survey, updation and printing of topographic sheets of National Map series on scale 1:50,000. iii. To provide geodetic control, heights and geographical positions all over Pakistan. iv. To compile derived maps on scale 1:250,000, 1:500,000, 1:1,000,000, 1:2,000,000, International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) charts on scale 1:1,000,000. v. To generate maps on any scale through aerial photography and remote sensing through analytical and digital methods. vi. To Develop Geographic Information System (GIS) for Govt., Semi Govt. departments/organizations/private sector according to their requirements on payment. vii. To survey & prepare cantonment areas maps. viii. To prepare and print Guide maps, District maps, Road maps & Tehsil maps for the entire country. ix. To train departmental employees and potential candidates from private sector in various disciplines of surveying and mapping in the Survey Training Institute at certificate and diploma levels. d. Organization: The department is headed by Surveyor General of Pakistan assisted by two Deputy Surveyor Generals.