Multi0page.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Capturing the Demographic Dividend in Pakistan

CAPTURING THE DEMOGRAPHIC DIVIDEND IN PAKISTAN ZEBA A. SATHAR RABBI ROYAN JOHN BONGAARTS EDITORS WITH A FOREWORD BY DAVID E. BLOOM The Population Council confronts critical health and development issues—from stopping the spread of HIV to improving reproductive health and ensuring that young people lead full and productive lives. Through biomedical, social science, and public health research in 50 countries, we work with our partners to deliver solutions that lead to more effective policies, programs, and technologies that improve lives around the world. Established in 1952 and headquartered in New York, the Council is a nongovernmental, nonprofit organization governed by an international board of trustees. © 2013 The Population Council, Inc. Population Council One Dag Hammarskjold Plaza New York, NY 10017 USA Population Council House No. 7, Street No. 62 Section F-6/3 Islamabad, Pakistan http://www.popcouncil.org The United Nations Population Fund is an international development agency that promotes the right of every woman, man, and child to enjoy a life of health and equal opportunity. UNFPA supports countries in using population data for policies and programmes to reduce poverty and to ensure that every pregnancy is wanted, every birth is safe, every young person is free of HIV and AIDS, and every girl and woman is treated with dignity and respect. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Capturing the demographic dividend in Pakistan / Zeba Sathar, Rabbi Royan, John Bongaarts, editors. -- First edition. pages ; cm Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 978-0-87834-129-0 (alkaline paper) 1. Pakistan--Population--Economic aspects. 2. Demographic transition--Economic aspects--Pakistan. -

COHRED Paper Research to Action and Policy PAKISTAN Mary Hilderbrand, Jonathan Simon, and Adnan Hyder Pakistan Faces a Wide Arra

COHRED paper Research to Action and Policy PAKISTAN Mary Hilderbrand, Jonathan Simon, and Adnan Hyder Pakistan faces a wide array of health challenges, including communicable diseases and nutritional deficiencies connected with poverty and low levels of development, as well as non- communicable conditions more commonly associated with affluent countries. The former are major contributors to the national disease burden. The extent to which they continue to threaten and diminish the well-being of Pakistan’s children is of particular concern. Conquering them will require a wide range of resources and actions, some well beyond the concerns of health policy. But how effectively health policy and programs address the challenges remains critical, and health research can potentially be an important contributor to effective, efficient, and equitable policies and programs. Since at least 1953, with the founding of the Pakistan Medical Research Council (PMRC), Pakistan has officially recognized the importance of research in solving the health problems of the country. There have been repeated calls for more support for health research and for such research to be utilized more fully in policy. The 1990 and 1998 National Health Policies both mentioned research utilization as important and pledged to strengthen it (Government of Pakistan, Ministry of Health, 1990 and 1998). A process of defining an essential national health research agenda occurred in the early nineties and recently has been rejuvenated (COHRED 1999). We conducted a study to understand better the role that research plays in child health policy and programs in Pakistan.1 In open-ended, in-depth interviews, we asked informants about their views on health research and policy generally in Pakistan and about their own experience in linking research with policy. -

SURVEY of PAKISTAN Rawalpindi INVITATION to BID Survey Of

SURVEY OF PAKISTAN Rawalpindi INVITATION TO BID Survey of Pakistan, a National Surveying & Mapping Agency invites sealed bids under the Project titled "Cadestral Mapping” under Single Stage• Two Envelop procedure from the firms registered with Income Tax & Sales Tax Departments for followings: i) Cadestral Mapping of Karachi City Zone-A ii) Cadestral Mapping of Karachi City Zone-B iii) Cadestral Mapping of Lahore City Zone-A iv) Cadestral Mapping of Lahore City Zone-B v) Cadestral Mapping of Statelands Sindh (Division Wise) vi) Cadestral Mapping of Statelands Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (Division Wise) vii) Cadestral Mapping of Statelands Punjab (Division Wise) viii) Cadestral Mapping of Sectors in CDA Islamabad 2). For Cadastral mapping of Statelands, the bids will be submitted for each Division of Provinces separately. Firms can apply for Cadastral Mapping of Statelands in one or Division depending upon their capacity. Bidding documents, containing detailed terms and conditions, technical specifications, method of procurement, procedure for submission of bids, bid security, evaluation criteria, performance guarantee etc., are available for the interested bidders at website of Public Procurement Regulatory Authority, which can be downloaded. 3). The bids, prepared in accordance with the instructions in the bidding documents, must reach at Survey of Pakistan, Faizabad Rawalpindi duly addressed to the Chairman Purchase Committee on or before 24-02-2021 at 10:30 hrs. Bids will be opened on the same day at 11:00 hrs. This advertisement is also available on PPRA's website at www.ppra.org.pk and Survey of Pakistan website www.sop.gov.pk. (Muhammad Tanvir) Director Directorate of Photogrammetry Chairman Purchase Committee 051-9290217 SURVEY OF PAKISTAN BID SOLICITATION DOCUMENT FOR AWARD OF CONTRACT OF CADASTRAL MAPPING OF CDA Survey of Pakistan, Faizabad, Murree Road, Rawalpindi Table of Contents 1 Project Overview .............................................................................................. -

Download PDF Copy of Political Map of Pakistan 2020

TAJIKISTAN C H I N G I L A 70 J & K G Peshawar ( FINAL STATUS NOT YET ISLAMABAD DETERMINED) I T Quetta Lahore 30 - B 60 GILGIT A Karachi Tropic of Cancer L T 80 S 20 I Karakoram Pass Junagadh & U N Manavadar INDUS RIVER S R A V T T E S Y K I A A O F P A N 1767 1947 1823 W H K N U INDUS RIVER Line of Control PAKISTAN T MUZAFFARABAD H Political K SRINAGAR A INDIAN ILLEGALLY OCCUPIED JAMMU & KASHMIR PESHAWAR Scale 1: 3,000,000 N (DISPUTED TERRITORY - FINAL STATUS TO BE DECIDED IN LINE WITH RELEVANT UNSC RESOLUTIONS) ISLAMABAD A R P E B T Y * H S W K orking Boundary I JHELUM RIVER N INDUS RIVER A LAHORE The red dotted line represents approximately the line of control in Jammu & Kashmir. The state of Jammu & Kashmir and its accession H CHENAB RIVER is yet to be decided through a plebiscite under the relevant United Nations Security Council Resolutions. G Actual boundary in the area where remark FRONTIER UNDEFINED P U N J A B appears, would ultimately be decided by the sovereign authorities VI RIVER F RA concerned after the final settlement of the Jammu & Kashmir dispute. *AJ&K stands for Azad Jammu & Kashmir as defined in the AJK Interim A Constitution Act, 1974. QUETTA N CHENAB RIVER SUTLEJ RIVER A A LEGEND T I Capital of Country . ISLAMABAD S Headquarters; Province . .PESHAWAR D Boundary; International . I INDUS RIVER Boundary; Province . N Boundary; Working . P Line of Control . -

Missed Immunization Opportunities Among Children Under 5 Years of Age Dwelling in Karachi City Asif Khaliq Aga Khan University, [email protected]

eCommons@AKU Department of Paediatrics and Child Health Division of Woman and Child Health October 2017 Missed immunization opportunities among children under 5 years of age dwelling In Karachi city Asif Khaliq Aga Khan University, [email protected] Sayeeda Amber Sayed Aga Khan University Syed Abdullah Hussaini Alberta Health Service Kiran Azam Ziauddin Medical University, Karachi Mehak Qamar Institute of Business Management, Karachi Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.aku.edu/ pakistan_fhs_mc_women_childhealth_paediatr Part of the Immunology and Infectious Disease Commons, and the Pediatrics Commons Recommended Citation Khaliq, A., Sayed, S., Hussaini, S., Azam, K., Qamar, M. (2017). Missed immunization opportunities among children under 5 years of age dwelling In Karachi city. Journal of Ayub Medical College, Abbottabad : JAMC, 29(4), 645-649. Available at: https://ecommons.aku.edu/pakistan_fhs_mc_women_childhealth_paediatr/388 J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad 2017;29(4) ORIGINAL ARTICLE MISSED IMMUNIZATION OPPORTUNITIES AMONG CHILDREN UNDER 5 YEARS OF AGE DWELLING IN KARACHI CITY Asif Khaliq, Sayeeda Amber Sayed*, Syed Abdullah Hussaini**, Kiran Azam***, Mehak Qamar*** Department of Paediatrics and Child Health, The Aga Khan University Hospital, Karachi, *Alberta Health Services, Calgary-Zone- Canada, **Ziauddin Medical University, Karachi, ***Department of Health and Hospital Management, Institute of Business Management, Karachi-Pakistan Background: Immunization is the safest and effective measure for preventing and eradicating various communicable diseases. A glaring immunization gap exists between developing and industrialized countries towards immunization, because the developing countries including Pakistan are still striving to provide basic immunization to their children. The purpose of this study was to access the prevalence and factors of missing immunization among under 5-year children of Karachi. -

Adding It Up: Costs and Benefits of Meeting the Contraceptive and Maternal and Newborn Health Needs of Women in Pakistan

Adding It Up: Costs and Benefits Of Meeting the Contraceptive and Maternal and Newborn Health Needs of Women in Pakistan Aparna Sundaram, Rubina Hussain, Zeba Sathar, Sabahat Hussain, Emma Pliskin and Eva Weissman Key Points ■■ Modern contraceptive services and maternal and newborn health care are essential for protecting the health of Pakistani women, their families and communities. ■■ Based on data from 2017, women in Pakistan have an estimated 3.8 million unintended pregnancies each year, most of which result from unmet need for modern contraception. ■■ About 52% of married women of reproductive age (15–49) who want to avoid a pregnancy are not using a modern contraceptive method. If all unmet need for modern contraception were met, there would be 3.1 million fewer unintended pregnancies annually, 2.1 million fewer induced abortions and nearly 1,000 fewer maternal deaths. ■■ Pakistan is currently spending US$81 million per year on contraceptive services. Serving the full unmet need for modern contraception would require an additional US$92 million per year, for a total of US$173 million, based on public-sector health care costs. ■■ At current levels of contraceptive use, providing maternal and newborn health care to all women who have unintended pregnancies, at the standards recommended by the World Health Organization, would cost an estimated US$298 million. ■■ If all women wanting to avoid a pregnancy used modern contraceptives and all pregnant women and their newborns received the recommended care, the country would save US$152 million, compared with a scenario in which only maternal and newborn health care were increased. -

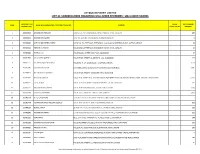

List of Unclaimed Shares and Dividend

ATTOCK REFINERY LIMITED LIST OF SHAREHOLDERS REGARDING UNCLAIMED DIVIDENDS / UNCLAIMED SHARES FOLIO NO / CDC SHARE NET DIVIDEND S/NO. NAME OF SHAREHOLDER / CERTIFICATE HOLDER ADDRESS ACCOUNT NO. CERTIFICATES AMOUNT 1 208020582 MUHAMMAD HAROON DASKBZ COLLEGE, KHAYABAN-E-RAHAT, PHASE-VI, D.H.A., KARACHI 450 2 208020632 MUHAMMAD SALEEM SHOP NO.22, RUBY CENTRE,BOULTON MARKETKARACHI 8 3 307000046 IGI FINEX SECURITIES LIMITED SUIT # 701-713, 7TH FLOOR, THE FORUM, G-20, BLOCK 9, KHAYABAN-E-JAMI, CLIFTON, KARACHI 15 4 307013023 REHMAT ALI HASNIE HOUSE # 96/2, STREET # 19, KHAYABAN-E-RAHAT, DHA-6, KARACHI. 15 5 307020846 FARRUKH ALI HOUSE # 246-A, STREET # 39, F-11/3, ISLAMABAD 67 6 307022966 SALAHUDDIN QURESHI HOUSE # 785, STREET # 11, SECTOR G-11/1, ISLAMABAD. 174 7 307025555 ALI IMRAN IQBAL MOTIWALA HOUSE NO. H-1, F-48-49, BLOCK - 4, CLIFTON, KARACHI. 2,550 8 307026496 MUHAMMAD QASIM C/O HABIB AUTOS, ADAM KHAN, PANHWAR ROAD, JACOBABAD. 2,085 9 307028922 NAEEM AHMED SIDDIQUI HOUSE # 429, STREET # 4, SECTOR # G-9/3, ISLAMABAD. 7 10 307032411 KHALID MEHMOOD HOUSE # 10 , STREET # 13 , SHAHEEN TOWN, POST OFFICE FIZAI, C/O MADINA GERNEL STORE, CHAKLALA, RAWALPINDI. 6,950 11 307034797 FAZAL AHMED HOUSE # A-121,BLOCK # 15,RAILWAY COLONY , F.B AREA, KARACHI 225 12 307037535 NASEEM AKHTAR AWAN HOUSE # 183/3 MUNIR ROAD , LAHORE CANTT LAHORE . 1,390 13 307039564 TEHSEEN UR REHMAN HOUSE # S-5, JAMI STAFE LANE # 2, DHA, KARACHI. 3,475 14 307041594 ATTIQ-UR-REHMAN C/O HAFIZ SHIFATULLAH,BADAR GENERALSTORE,SHAMA COLONY,BEGUM KOT,LAHORE 7 15 307042774 MUHAMMAD NASIR HUSSAIN SIDDIQUI HOUSE-A-659,BLOCK-H, NORTH NAZIMABAD, KARACHI. -

THE PAKISTAN EXPANDED PROGRAM on IMMUNIZATION and the NATIONAL IMMUNIZATION SUPPORT PROJECT: Public Disclosure Authorized an ECONOMIC ANALYSIS

THE PAKISTAN EXPANDED PROGRAM ON IMMUNIZATION AND THE NATIONAL IMMUNIZATION SUPPORT PROJECT: Public Disclosure Authorized AN ECONOMIC ANALYSIS DISCUSSION PAPER NOVEMBER 2016 Public Disclosure Authorized Minhaj ul Haque Muhammad Waheed Tayyeb Masud Wasim Shahid Malick Hammad Yunus Rahul Rekhi Robert Oelrichs Oleg Kucheryavenko Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized THE PAKISTAN EXPANDED PROGRAM ON IMMUNIZATION AND THE NATIONAL IMMUNIZATION SUPPORT PROJECT An Economic Analysis Minhaj ul Haque, Muhammad Waheed, Tayyeb Masud, Wasim Shahid Malick, Hammad Yunus, Rahul Rekhi, Robert Oelrichs, and Oleg Kucheryavenko November 2016 1 Health, Nutrition and Population (HNP) Discussion Paper This series is produced by the Health, Nutrition, and Population Global Practice. The papers in this series aim to provide a vehicle for publishing preliminary results on HNP topics to encourage discussion and debate. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this paper are entirely those of the author(s) and should not be attributed in any manner to the World Bank, to its affiliated organizations or to members of its Board of Executive Directors or the countries they represent. Citation and the use of material presented in this series should take into account this provisional character. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of The World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. For information regarding the HNP Discussion Paper Series, please contact the Editor, Martin Lutalo at [email protected] or Erika Yanick at [email protected]. -

Workshop Summary One Health Zoonotic Disease Prioritization & One Health Systems Mapping and Analysis Resource Toolkit™ for Multisectoral Engagement in Pakistan

Workshop Summary One Health Zoonotic Disease Prioritization & One Health Systems Mapping and Analysis Resource Toolkit™ for Multisectoral Engagement in Pakistan Islamabad, Pakistan CS 293126-A ONE HEALTH ZOONOTIC DISEASE PRIORITIZATION & ONE HEALTH SYSTEMS MAPPING AND ANALYSIS RESOURCE TOOLKIT™ FOR MULTISECTORAL ENGAGEMENT Photo 1. Waterfall in Skardu. ii ISLAMABAD, PAKISTAN AUGUST 22–25, 2017 ONE HEALTH ZOONOTIC DISEASE PRIORITIZATION & ONE HEALTH SYSTEMS MAPPING AND ANALYSIS RESOURCE TOOLKIT™ FOR MULTISECTORAL ENGAGEMENT TABLE OF CONTENTS Participating Organizations .................................................................................................................. iv Summary ................................................................................................................................................... 1 Background .............................................................................................................................................. 5 Pakistan’s National One Health Platform .................................................................................................................5 One Health Zoonotic Disease Prioritization and One Health Systems Mapping and Analysis Resource Toolkit Workshop .................................................................................................................... 7 Workshop Methods ................................................................................................................................. 8 One Health Zoonotic -

Pakistan's Role in Reducing the Global Burden of Reproductive, Maternal, Newborn, and Child Health

Ghaffar et al. Health Research Policy and Systems 2015, 13(Suppl 1):48 DOI 10.1186/s12961-015-0035-6 COMMENTARY Open Access Credit where credit is due: Pakistan’s role in reducing the global burden of reproductive, maternal, newborn, and child health (RMNCH) Abdul Ghaffar1*, Shamim Qazi2 and Iqbal Shah3 Abstract Factors contributing to Pakistan’s poor progress in reducing reproductive, maternal, newborn, and child health (RMNCH) include its low level of female literacy, gender inequity, political challenges, and extremism along with its associated relentless violence; further, less than 1% of Pakistan’s GDP is allocated to the health sector. However, despite these disadvantages, Pakistani researchers have been able to achieve positive contributions towards RMNCH-related global knowledge and evidence base, in some cases leading to the formulation of WHO guidelines, for which they should feel proud. Nevertheless,inordertoimprovethehealthofitsownwomenand children, greater investments in human and health resources are required to facilitate the generation and use of policy-relevant knowledge. To accomplish this, fair incentives for research production need to be introduced, policy and decision-makers’ capacity to demand and use evidence needs to be increased, and strong support from development partners and the global health community must be secured. Keywords: Capacities, Context, Global knowledge, Incentives Background the health sector [3]. Its expenditure record is certainly Pakistan is the sixth most populous country in the world. not outstanding, even compared to neighbouring coun- With the second and third highest rates of stillbirths and tries with relatively poorer economic indicators, but it newborn mortality [1], respectively, its progress towards is reasonable given the challenges it continues to face. -

1 National TB Control Program Ministry of National Health Services

National TB Control Program Ministry of National Health Services Regulations & Coordination Islamabad, Pakistan 1 Annual Report 2013 National TB Control Program Ministry of National Health Services Regulations & Coordination Islamabad, Pakistan 2 Editorial Oversight: Dr. Ejaz Qadeer, National Manager NTP Coordination:3 Wasim Bari Compiled By: Ms. Ammara Omer Contents Acronyms 6 Message by DG NHSR&C 8 Message by National Program Manager 9 Executive Summary 10 1. Epidemiology 12 2. National TB Control Program 13 3. Principle Recipients 22 4. Operational Research 28 5. Drug Management 34 6. Advocacy Communication & Social Mobilization Infection Control 37 7. PPM (Public Private Mix 42 8. MDR-TB 50 9. Hospital Dots Linkages 53 10. Infection Control 56 11. TB / HIV 60 12. National Reference Laboratory 66 13. Health System Strengthening 80 4 Acronyms ACSM Advocacy, Communication and Social Mobilization AIDS Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome AJK Azad Jammu and Kashmir AKHSP Aga Khan Health Services Pakistan BCC Behavior Change Communication BDN Basic Development Needs CBOs Community-Based Organizations DCO District Coordination Officer DFID Department for International Development DOTS Directly Observed Treatment Short-course DTC District TB Coordinator EDO (H) Executive District Officer-Health EQA External Quality Assurance GFATM Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria GLRA German Leprosy and TB Relief Association GS Green Star GTZ GesellschaftfürTechnischeZusammenarbeit HIV Human Immunodeficiency Virus IACC Inter-Agency Coordination -

Fighting Against the Reemergence of Polio in the Federally Administered Tribal Areas of Pakistan

Loyola University Chicago International Law Review Volume 13 Issue 1 Article 4 2016 Fighting Against The Reemergence of Polio in the Federally Administered Tribal Areas of Pakistan Basim Kamal Follow this and additional works at: https://lawecommons.luc.edu/lucilr Part of the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Basim Kamal Fighting Against The Reemergence of Polio in the Federally Administered Tribal Areas of Pakistan, 13 Loy. U. Chi. Int'l L. Rev. 57 (2016). Available at: https://lawecommons.luc.edu/lucilr/vol13/iss1/4 This Student Article is brought to you for free and open access by LAW eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Loyola University Chicago International Law Review by an authorized editor of LAW eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FIGHTING AGAINST THE REEMERGENCE OF POLIO IN THE FEDERALLY ADMINISTERED TRIBAL AREAS OF PAKISTAN Basim Kamal I. Introduction ................................................... 57 II. B ackground ................................................... 58 A. Federally Administered Tribal Areas of Pakistan ............ 58 B. Polio Eradication in Pakistan .............................. 59 III. D iscussion .................................................... 6 1 IV . A nalysis ...................................................... 63 A . Security .................................................. 63 B. M ism anagement ........................................... 64 C . M isinform ation ............................................ 65 V . Proposal .....................................................