Introduction to Navigation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Operational Policy

Operational policy Visitor management Orienteering and rogaining in QPWS-managed areas Operational policies provide a framework for consistent application and interpretation of legislation and for the management of non-legislative matters by the Environmental Protection Agency (incorporating the Queensland Parks and Wildlife Service). Operational policies are not intended to be applied inflexibly in all circumstances. Individual circumstances may require a modified application of policy. Policy subject This policy outlines the circumstances in which the Queensland Parks and Wildlife Service (QPWS) may authorise and manage the conduct of orienteering and rogaining activities on QPWS-managed areas. Background While QPWS-managed areas provide a range of opportunities for different visitor activities, not all activities can be accommodated, as requirements for conserving natural and cultural values and other considerations including impacts on other uses, management programs, priority community needs and equity dictate against some activities. Orienteering and rogaining activities vary from relatively informal, small scale gatherings to large scale championship or carnival events. Such events can give rise to a range of issues and impacts, including damage to vegetation, disturbance of wildlife and possible disruption of other visitor activities. Further information on these activities is contained in Attachment 1. The particular scale and format of an event or events will determine the extent to which impacts are concentrated or dispersed across the landscape. Particular environments have different conservation and cultural significance and are more or less sensitive (resistant and/or resilient) to particular types, frequencies and intensities of use. Each of these factors will be critical in identifying the risks associated with proposed orienteering and rogaining activities, and in assessing and determining applications to conduct such activities. -

Memorandum of Understanding Between Forests New South Wales

Memorandum of Understanding between Forests New South Wales and The Orienteering Association of NSW The New South Wales Rogaining Association CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION.......................................................................................................... 3 2. PURPOSE OF THE DOCUMENT................................................................................... 3 3. ROLE AND RESPONSIBILITY OF FORESTS NSW......................................................... 3 4. ROLE AND RESPONSIBILITY OF THE ORIENTEERING ASSOCIATION OF NEW SOUTH WALES.............................................................................................................................. 4 5. ROLE AND RESPONSIBILITY OF THE NSW ROGAINING ASSOCIATION ....................... 4 6. OPERATING FRAMEWORK......................................................................................... 5 6.1 Communication.................................................................................................... 5 6.2 Planning.............................................................................................................. 5 6.3 Permit Application Process .................................................................................... 5 6.3.1 State-wide Special Purpose Permit Application.....................................................................................5 6.3.2 Special Regional Arrangements .......................................................Error! Bookmark not defined. 6.3.2 General...............................................................................................................................................7 -

Inquiry Into the 2011 Kimberley Ultramarathon

Economics and Industry Standing Committee Inquiry into the 2011 Kimberley Ultramarathon Report No. 13 Legislative Assembly August 2012 Parliament of Western Australia Committee Members Chair Mr M.D. Nahan, MLA Member for Riverton Deputy Chair Mr W.J. Johnston, MLA Member for Cannington Members Ms A.R. Mitchell, MLA Member for Kingsley Mr I.C. Blayney, MLA Member for Geraldton Mr M.P. Murray, MLA Member for Collie-Preston Co-opted Member Hon. M.H. Roberts, MLA Member for Midland Committee Staff Principal Research Officer Mr Tim Hughes, BA (Hons) Ms Renée Gould, BA GradDipA (from 16 April 2012) Research Officer Mrs Kristy Bryden, BA, BCom Legislative Assembly Tel: (08) 9222 7494 Parliament House Fax: (08) 9222 7804 Harvest Terrace Email: [email protected] PERTH WA 6000 Website: www.parliament.wa.gov.au/eisc Published by the Parliament of Western Australia, Perth. August 2012. ISBN: 978-1-921865-53-4 (Series: Western Australia. Parliament. Legislative Assembly. Committees. Economics and Industry Standing Committee. Report 13) 328.365 Economics and Industry Standing Committee Inquiry into the 2011 Kimberley Ultramarathon Report No. 13 Presented by Dr M.D. Nahan, MLA Laid on the Table of the Legislative Assembly on 16 August 2012 Contents Executive Summary i Ministerial Response xi Findings and Recommendations xiii Relevant Persons xxv 1 Introduction 1 The 2011 Kimberley Ultramarathon 1 2 RacingthePlanet Events Limited 7 Part One: Risk identification and assessment 7 Risk of fire in the course area 7 RacingThePlanet’s awareness of -

PHYSICAL N Programme Ideas

S.Pmfecl Inspiring a million VOLUNTEERING more young PHYSICAL volunteers Programme ideas: Volunteering section Programme ideas: Physical section When completing each section of your DofE, you It's your choice... When completing each section of your DofE, you It's your choice... should develop a programme which is specific Volunteering gives you the chance to make a should develop a programme which is specific Doing physical activity is fun and improves your and relevant to you. This sheet gives you a list of difference to people's lives and use your skills and and relevant to you. This sheet gives you a list health and physical fitness. There's an activity to prograrnme ideas that you could do or you could experience to help your local community. You of programme ideas that you could do or you suit everyone so choose something you are really use it as a starting point to create a Volunteering can use this opportunity to become involved in a could use it as a starting point to create a Physical interested in. programme of your own! project or with an organisation that you care about. programme of your own! Help with planning For each idea, there is a useful document Help with planning For each idea, there is a useful document You can use the handy programme planner on giving you guidance on how to do it, which You can use the handy programme planner on giving you guidance on how to do it, which the website to work with your Leader to plan you can find under the category finder on the website to work with your Leader to plan you can find under the category finder on your activity. -

SUGAR HILL ROGAINE II CNYO's 20 ANNUAL ROGAINE 2010

SUGAR HILL ROGAINE II CNYO’s 20th ANNUAL ROGAINE 2010 UNITED STATES ROGAINING CHAMPIONSHIPS Date: July 31-August 1, 2010 Time: Mass start at noon on Saturday. Map issue for planning at 10am on Saturday. Duration: There will be options for 6, 12, and 24 hours. Only the 24 hour event is the official US Rogaining Championships. See more details further down about award categories and eligibility requirements. What is a Rogaine? The concept is very straightforward—teams of two to five people have a fixed time (6, 12, or 24 hours in this event) to visit as many checkpoints as possible, walking, running or resting as they see fit. The checkpoints (controls) are spread over a large area, and are pre-marked on a map issued shortly before the start of the event. Point values for visiting each control vary (and are specified in advance) depending on such factors as the distance from the start/finish area, elevation, navigational complexity, and the whims of the course setter. The members of the team must stay together throughout the event, for reasons of safety. Who may participate? Participants in rogaining come from diverse backgrounds, including hikers, cross-country runners, trail runners, adventure racers, ultra-runners, orienteers, and family groups. Even at a championship event such as this, a wide variety of competitive intensity is found, varying from the casual stroller wanting to add some variety to the weekend hike to serious athletes expecting to vie for the top spots in their category, going with no sleep and at a running pace for most of the event. -

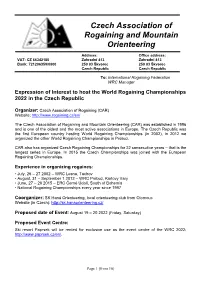

Czech Association of Rogaining and Mountain Orienteering (CAR) Was Established in 1996 and Is One of the Oldest and the Most Active Associations in Europe

Czech Association of Rogaining and Mountain Orienteering Address: Office address: VAT: CZ 66342180 Zahradní 413 Zahradní 413 Bank: 721206359/0800 250 83 Škvorec 250 83 Škvorec Czech Republic Czech Republic To: International Rogaining Federation WRC Manager Expression of Interest to host the World Rogaining Championships 2022 in the Czech Republic Organizer: Czech Association of Rogaining (CAR) Website: http://www.rogaining.cz/en/ The Czech Association of Rogaining and Mountain Orienteering (CAR) was established in 1996 and is one of the oldest and the most active associations in Europe. The Czech Republic was the first European country hosting World Rogaining Championships (in 2002), in 2012 we organized the other World Rogaining Championships in Prebuz. CAR also has organized Czech Rogaining Championships for 22 consecutive years – that is the longest series in Europe. In 2015 the Czech Championships was joined with the European Rogaining Championships. Experience in organizing rogaines: • July, 26 – 27 2002 – WRC Lesna, Tachov • August, 31 – September 1 2012 – WRC Prebuz, Karlovy Vary • June, 27 – 28 2015 – ERC Černé Údolí, South of Bohemia • National Rogaining Championships every year since 1997 Coorganizer: SK Haná Orienteering, local orienteering club from Olomouc Website (in Czech): http://sk.hanaorienteering.cz/ Proposed date of Event: August 19 – 20 2022 (Friday, Saturday) Proposed Event Centre: Ski resort Paprsek will be rented for exclusive use as the event centre of the WRC 2022: http://www.paprsek.cz/en/. Page 1 (from 10) -

18Th Russian Rogaining Championships Zalesye 2021

18TH RUSSIAN ROGAINING CHAMPIONSHIPS ZALESYE 2021 May 8-9, 2021, Vladimir and Yaroslavl regions Dear friends! It is great honor for us to host participants of the 18th Russian Rogaining Championships Zalesye 2021, and we are glad that for the first time the large rogaine enters to the territory of the Zalesye, the location with ancient historical roots and beautiful Russian nature. In 2021 Russia celebrates the 800th anniversary of the birth of Grand Duke Alexander Nevsky, a large number of events will be organized in the territory of Pereslavl-Zalessky, the city that is the birthplace of the Grand Duke. Such a significant event as the Russian Rogaining Championships in the territories of Vladimir and Yaroslavl regions is held for the first time. Therefore the team of the Genesis sports project and Nizhny Novgorod rogaine which organized the Russian Rogaining Championships 2017 in Nizhny Novgorod region and the Oka Trail project participate as the partners. We are sure that this Championship will be a bright event in the history of the development of rogaine and outdoor sports in the country. Participants will enjoy the diverse terrain and the high level of organization of the event. The participation of foreign athletes is planned, the Russian Championships have open status. As supporters will be prepared 8- and 4-hour formats of the rogaine, for a wide range of the participants who are not indifferent to the beauty of Russian nature, who want to touch the ancient history and culture of Zalesye. For the participants who want to broaden their horizons and to have a great weekend in the eve of the Championships, we elaborate with the institutions of Pereslavl-Zalessky the cultural program related to the nature and the history of the region. -

Orienteering, Rogaining and Navigation Activities V2.0

ORIENTEERING, ROGAINING AND NAVIGATION EFFECTIVE: 1 JANUARY 2021 VERSION: 2.0 2 ORIENTEERING, ROGAINING AND NAVIGATION This document contains specific requirements related to orienteering, rogaining and navigation activities, and must be read in conjunction with the Appendix A: General Requirements in the Recreation and Outdoor Education Activities for Public Schools Procedures. 1. BACKGROUND Orienteering, rogaining and navigation activities focus on the use and interpretation of maps in outdoor environments, with or without the aid of a compass for navigation. Navigation activities are generally suitable for a wide range of age groups. Beginners may be introduced to the skills of navigation using a simple map to locate points around a school environment. As a student’s skill set progresses, more capable participants may be challenged by completing more difficult courses set in a natural environment. DEFINITIONS ASSISTANT SUPERVISOR Assists the Qualified Supervisor and or Department teacher-in-charge. May or may not have relevant qualification or experience. NAVIGATION ACTIVITIES An activity where participants find their way around a predetermined course using a large scale orienteering map in natural environments with or without a compass. ORIENTEERING A competitive sport where participants navigate their way around a predetermined course using a large scale orienteering map with or without the use of a compass, at speed. QUALIFIED SUPERVISOR Has the required qualifications, skill, experience and technical knowledge to instruct the activity. REMOTE OR ISOLATED AREAS Includes any location where medical emergency assistance is more than one hour away by road and/or air. ROGAINING The sport of long distance cross-country navigation in which teams of two to five members visit as many checkpoints as possible in 24 hours. -

Maps for Different Forms of Orienteering

MAPS FOR DIFFERENT FORMS OF ORIENTEERING László Zentai Eötvös Loránd University, Pázmány Péter sétány 1/A H-1117 Budapest, Hungary [email protected] Abstract: Orienteering became a worldwide sport in the last 25-30 years. Orienteering maps are one of the very few types of maps that have the same specifications all over the world. Orienteering maps are special, because to make them suitable for orienteering the map makers have to be familiar not only with the map specifications, but also with the rules and traditions of the sport. The early period of orienteering maps was the age of homemade maps. Maps were made by orienteers using available tourist or topographic maps and only after the availability of cheaper reproduction techniques started the process of special field- working. The International Orienteering Federation (IOF) was formed in 1961. The Map Commission (MC) of the IOF has introduced different specifications for the official disciplines (before 2000 the ski-orienteering and foot-orienteering were the only official disciplines). The last version of the specification, the International Standard for Orienteering Maps (ISOM) was published in 2000 and included specifications for foot- orienteering, ski-orienteering, mountain-bike orienteering. A new format, the sprint competition, required new map specifications (ISSOM) which were finalized and published in 2007. The aim of orienteering map specifications is to provide rules that can accommodate many different types of terrain around the world and various forms of orienteering. We can use the experience of the official disciplines for developing new specifications: the official disciplines and formats were developed in the past 30 years (most of them are even newer). -

Community Cycling News

CYCLETHE MEMBERS’ MAGAZINE - No. 191 AUGUST TO OCTOBER 2021 COMMUNITY CYCLING NEWS SEA OTTER FESTIVAL A CRUCIAL STEP FOR BIKE SA RUPERT’S CROSS- CONTINENTAL EXPRESS IT’S TIME FOR REAL ROAD CONGESTION SOLUTIONS CONTENTS BICYCLE SA OFFICE Front cover image: 11A Croydon Road, Keswick SA 5035 Elite racing will be on show at Sea Otter Australia. Phone (08) 8168 9999 Fax (08) 8168 9988 CEO and President’s Notes 3, 7 Email [email protected] Web www.bikesa.asn.au Sea Otter Festival is a Vital, Exciting Step For Bike SA 4-6 @BicycleSA @bicyclesa Congestion Busting Starts with Busting @bike_sa the Old, Failed Model 7 Bicycle SA Cross-Continental Express – Rupert’s Ride The Bike SA office is open Mondays to Thursdays, 9am to 5pm for Health and Hope 8-9 Outback Odyssey 2021 10 CYCLE Join The Ride For Fun, Friendship and a Sea Otter Festival Crucial — page 4-6 Cycle is published quarterly Better Future 11 ISSN: 2208-3979 Riding Their Way to a Rare Achievement 13 DISCLAIMER The views expressed in this magazine are not MEMBER SUBMISSIONS necessarily those of Bicycle SA. Bicycle SA does After A New Cycling Challenge? not guarantee the accuracy of information Try Velogaine 12 published herein. © 2021 BICYCLE SA Original articles in Cycle are copyrighted to Bicycle South Australia Incorporated (Bicycle SA) unless otherwise specified. Non-profit organisations may reproduce articles copyrighted to Bicycle SA, with only minor modification, without the permission of the authors, provided Bicycle SA is sent, as a courtesy and condition, a copy of the publications Cross-Continental Express— page 8/9 containing such reproduction. -

List of Sports

List of sports The following is a list of sports/games, divided by cat- egory. There are many more sports to be added. This system has a disadvantage because some sports may fit in more than one category. According to the World Sports Encyclopedia (2003) there are 8,000 indigenous sports and sporting games.[1] 1 Physical sports 1.1 Air sports Wingsuit flying • Parachuting • Banzai skydiving • BASE jumping • Skydiving Lima Lima aerobatics team performing over Louisville. • Skysurfing Main article: Air sports • Wingsuit flying • Paragliding • Aerobatics • Powered paragliding • Air racing • Paramotoring • Ballooning • Ultralight aviation • Cluster ballooning • Hopper ballooning 1.2 Archery Main article: Archery • Gliding • Marching band • Field archery • Hang gliding • Flight archery • Powered hang glider • Gungdo • Human powered aircraft • Indoor archery • Model aircraft • Kyūdō 1 2 1 PHYSICAL SPORTS • Sipa • Throwball • Volleyball • Beach volleyball • Water Volleyball • Paralympic volleyball • Wallyball • Tennis Members of the Gotemba Kyūdō Association demonstrate Kyūdō. 1.4 Basketball family • Popinjay • Target archery 1.3 Ball over net games An international match of Volleyball. Basketball player Dwight Howard making a slam dunk at 2008 • Ball badminton Summer Olympic Games • Biribol • Basketball • Goalroball • Beach basketball • Bossaball • Deaf basketball • Fistball • 3x3 • Footbag net • Streetball • • Football tennis Water basketball • Wheelchair basketball • Footvolley • Korfball • Hooverball • Netball • Peteca • Fastnet • Pickleball -

BARK Newsletter

Bend Adventure Racing Klub News April, 2004 The Sharing adventure in the outdoors BBAARRKK a.k.a www.BARKracing.com “Getting Lost Together” Old BARK Bests Young BARK at Rogaine —What‘s a Rogaine?“ is the first question I‘m asked indistinct but rough sagebrush and lava rock of the when describing last weekend‘s race. —Is it a race desert seemed plenty. to grow hair?“ No, and it‘s not sponsored by a large pharmaceutical company. A rogaine is a type of Final Score: Young BARK- 1630; Old BARK- 1720. orienteering event and, on April 4th, several Bring on the Black Butte Porter! BARKers competed in the High Desert Drifter 6- Hour Mini-Rogaine organized by the Oregon By the way, "rogaine" is an Cascades Orienteering Klub. acronym that was invented in the 1970s from Rugged Outdoor Rogaining is the sport of long distance cross- Group Activity Involving country navigation in which teams visit as many Navigation and Endurance, or checkpoints (called control points in orienteering from a combination of the lingo) as possible in a given time period. This type inventor's names (ROd, GAIl, and of event is also called Score-O because each control NEil), depending on who you ask. is given a point value, sometimes different amounts Or you can go do a Billy Goat. based of difficulty, and the team with the most points wins. Teams can visit controls in any order - Pam Stevenson and must plan their course to get the maximum number of points. They navigate by map and compass between points that are marked with Volunteer for the distinctive orange and white control markers.