Journal of Ukrainian Studies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report - 2007 Vernadsky National Library of Ukraine Kyiv, Ukraine

Conference of European National Libraries CENL - Annual Report - 2007 Vernadsky National Library of Ukraine Kyiv, Ukraine Address: Director General Academician O.S.Onyschenko Prospekt 40-richja Zhovtnja,3 Kyiv-39 Ukraine 03039 Tel: +39 044 525 81 04 Fax: +39 044 524 33 98 E-mail: [email protected] URL: http://www.nbuv.gov.ua 1. Management of the Library Vernadsky National Library of Ukraine (VNLU) is the main scientific-informational centre of the country, national book-store and scientific centre of bibliography, studies in books and library science, which is under the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine. The Fund of the Presidents of Ukraine, the National legal library, the Service of informational-analytical ensuring of the State bodies function in Vernadsky National Library of Ukraine. In the VNLU structure there are 39 departments, which according to their activity were grouped in the institutes (of library science, of Ukrainian book, of manuscripts, of archives science, of bibliographic researches), centers (of bibliotheka-informational technologies, of formation of library and information resources, of conservation and restoration, of cultural-enlightening, scientific-publishing). The direction of the Library consists of: Director General, 5 Assistant Managers. The direction works out and confirms programs, strategic and financial plans, adopts and caries out the annual plan, budget and long-lasting capital investments. The V. Vernadsky National library of Ukraine scientific council is the collegial board of the Library scientific activity’s managing. This board is responsible for the scientific activities main directions determination, analyzing of the scientific researches realization state, material, technical and financial providing of the scientific researches, for training of personnel, for approving of the programs and projects of scientific and researches activities. -

Liudmyla Hrynevych the Price of Stalin's “Revolution from Above

Liudmyla Hrynevych The Price of Stalin’s “Revolution from Above”: Anticipation of War among the Ukrainian Peasantry On the whole, the Soviet industrialization program, as defined by the ideological postulate on the inevitability of armed conflict between capitalism and socialism and implemented at the cost of the merciless plundering of the countryside, produced the results anticipated by the Stalinist leadership: the Soviet Union made a great industrial leap forward, marked first and foremost by the successful buildup of its military-industrial complex and the modernization of its armed forces.1 However, the Bolshevik state’s rapid development of its “steel muscle” led directly to the deaths of millions of people—the Soviet state’s most valuable human resources—and the manifestation of an unprecedented level of disloyalty to the Bolshevik government on the part of a significant proportion of the Soviet population, particularly in Ukraine, not seen since the civil wars fought between 1917 and the early 1920s. The main purpose of this article is to establish a close correlation between the Stalinist “revolution from above,” the Holodomor tragedy, and the growth of anti-Soviet moods in Ukrainian society in the context of its attitude to a potential war. The questions determining the intention of this article may be formulated more concretely as follows: How did the population of the Ukrainian SSR imagine a possible war? What was the degree of psychological preparedness for war? And, finally, the main question: To what extent did political attitudes in Ukrainian society prevalent during the unfolding of the Stalinist “revolution from above” correspond to the strategic requirement of maintaining the masses’ loyalty to the Soviet government on an adequate level as a prerequisite for the battle-readiness of the armed forces and the solidity of the home front? Soviet foreign-policy strategy during the first decade after the end of the First World War resembled the two-faced Roman god Janus. -

Download File

BEYOND RESENTMENT Mykola Riabchuk Vasyl Kuchabsky, Western Ukraine in Conflict with Poland and Bolshevism, 1918-1923. Translated from the German by Gus Fagan. Edmomton and Toronto: Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies Press, 2009. 361 pp. + 6 maps. t might be a risky enterprise to publish a historical of Western Ukrainians to establish their independent monograph written some eighty years ago, which at republic on the ruins of the Habsburg empire—in full the time addressed the very recent developments of line with the prevailing Wilsonian principle of national I1918-1923—this would seem to be much more suited toself-determination, the right presumably granted by the lively memoirs than a cool-blooded analysis and archival victorious Entente to all East European nations. Western research. Indeed, since 1934 when Vasyl Kuchabsky's Ukraine is in the center of both the title and the narrative, Die Westukraine im Kampfe mit Polen und dem and this makes both the book and its translation rather Bolschewismus in den Jahren 1918-1923 was published important, since there are still very few “Ukrainocentric” in Germany in a small seminar series, a great number of accounts of these events, which though not necessarily books and articles on the relevant topics have appeared, opposing the dominant Polish and Russian perspectives, and even a greater number of archival documents, letters at least provide some check on the myths and biases and memoirs have become accessible to scholars. and challenge or supplement the dominant views with Still, as Frank Sysyn rightly points out in his short neglected facts and alternative interpretations. -

The Jews of Ukraine and Moldova

CHAPTER ONE THE JEWS OF UKRAINE AND MOLDOVA by Professor Zvi Gitelman HISTORICAL BACKGROUND A hundred years ago, the Russian Empire contained the largest Jewish community in the world, numbering about 5 million people. More than 40 percent—2 million of them—lived in Ukraine SHIFTING SOVEREIGNTIES and Bessarabia (the latter territory was subsequently divided Nearly a thousand years ago, Moldova was populated by a between the present-day Ukraine and Moldova; here, for ease Romanian-speaking people, descended from Romans, who of discussion, we use the terms “Bessarabia” and “Moldova” intermarried with the indigenous Dacians. A principality was interchangeably). Some 1.8 million lived in Ukraine (west of established in the territory in the fourteenth century, but it the Dniepr River) and in Bessarabia, and 387,000 made their did not last long. Moldova then became a tributary state of homes in Ukraine (east of the Dniepr), including Crimea. the Ottoman Empire, which lost parts of it to the Russian Thousands of others lived in what was called Eastern Galicia— Empire in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. now Western Ukraine. After the 1917 Russian Revolution, part of Moldova lay Today the Jewish population of those areas is much reduced, within the borders of Romania. Eventually part of it became due to the cumulative and devastating impacts of World War I, the Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic (SSR) of Moldavia, the 1917 Russian Revolution, World War II and the Holocaust, a unit within the larger Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic. massive emigration since the 1970s, and a natural decrease In August 1940, as Eastern Europe was being carved up resulting from a very low birth rate and a high mortality rate. -

WEST EAST MIP 06122018 All.Indd

Купить книгу на сайте kniga.biz.ua >>> AUTHOR’S NOTE A 25 000 kilometers long journey in Ukraine their knowledge and their experiences. I tried all is how one could describe the contents of the the dishes of the regional cuisine and wrote down book you are holding in your hands now. It was all the recipes. I visited and tried all the hotels and an approximate mileage of the odometer of my restaurants I mentioned in the book, choosing Subaru Forester SUV was during the last two years, only the best ones or those that didn’t have any while I was roaming in the country, exploring lots alternative at all, if there were no other options of familiar as well as some new routes, driving on available in the area. However, some of the splendid highways and forcing my way off road, establishments and businesses described here visiting big cities and small remote villages and could have been shut down since the moment discovering various resorts, both developing of publication of this book, although some new ones and those going into decline. My goal was ones could have been opened as well. I made the wonders of nature and historical sights, well- sure to write separately about the conditions of advertised nature reserves and forgotten ruins, the roads on all the routes I was writing about, calm and quiet beaches and death-defying rides. which I consider being extremely important while And of course, my primary goal was all those choosing the direction of a trip. interesting people who really love their country, If you opened this book, it means that you who genuinely care about its future and actually either belong to the travellers’ tribe already or do something in order to increase its attractiveness seriously consider the possibility to really see to the tourists. -

Newsletter #7

NEWSLETTER #7 18.12.2017 Innovations in decentralisation: the very first in Ukraine Mobile Administrative Service Centre was launched with support from U-LEAD with Europe Programme A Mobile ASC is a specially equipped vehicle with workstations for two administrators and room for three visitors. The Mobile ASC can provide 80 types of services for citizens of remote areas. Slavuta community in Khmelnytskyi oblast is U-LEAD’s pilot region for implementation of the “mobile” format of administrative service delivery. The Mobile ASC will visit the residents of remote towns and villages on a regular basis and run 5 routes covering 20 settlements during the course of a week. It will provide access to high quality services for more than 8,000 residents of the remote areas in Slavuta community, including pensioners and people with disabilities. The mobile ASC is equipped with the terminal for cashless payments and the revenues from the administrative services will be credited to the community budget. In case of pilot’s success in Slavuta, it will be replicated in other Ukrainian communities. The “U-LEAD with Europe” Programme’s team jointly with the Vice-Prime-Minister, Minister of Regional Development, Hennadii Zubko, presented the mobile ASC in Kyiv on December 4th at the 2nd All-Ukrainian Forum for amalgamated communities. The event was attended by the President, the Head of the Parliament, Prime-Minister and heads of the amalgamated communities. At the ceremony of the ASC opening in Slavuta (which took place on November 30th), the Ambassador of Sweden to Ukraine, Martin Hagström, and the Adviser on Decentralization of the EU Delegation to Ukraine, Benedikt Herrmann, highly praised the partnership between the community and Swedish and Ukrainian experts and its role in development of accessible, high quality administrative services and good governance in Ukraine. -

Jewish Cemetries, Synagogues, and Mass Grave Sites in Ukraine

Syracuse University SURFACE Religion College of Arts and Sciences 2005 Jewish Cemetries, Synagogues, and Mass Grave Sites in Ukraine Samuel D. Gruber United States Commission for the Preservation of America’s Heritage Abroad Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/rel Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Gruber, Samuel D., "Jewish Cemeteries, Synagogues, and Mass Grave Sites in Ukraine" (2005). Full list of publications from School of Architecture. Paper 94. http://surface.syr.edu/arc/94 This Report is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts and Sciences at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Religion by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. JEWISH CEMETERIES, SYNAGOGUES, AND MASS GRAVE SITES IN UKRAINE United States Commission for the Preservation of America’s Heritage Abroad 2005 UNITED STATES COMMISSION FOR THE PRESERVATION OF AMERICA’S HERITAGE ABROAD Warren L. Miller, Chairman McLean, VA Members: Ned Bandler August B. Pust Bridgewater, CT Euclid, OH Chaskel Besser Menno Ratzker New York, NY Monsey, NY Amy S. Epstein Harriet Rotter Pinellas Park, FL Bingham Farms, MI Edgar Gluck Lee Seeman Brooklyn, NY Great Neck, NY Phyllis Kaminsky Steven E. Some Potomac, MD Princeton, NJ Zvi Kestenbaum Irving Stolberg Brooklyn, NY New Haven, CT Daniel Lapin Ari Storch Mercer Island, WA Potomac, MD Gary J. Lavine Staff: Fayetteville, NY Jeffrey L. Farrow Michael B. Levy Executive Director Washington, DC Samuel Gruber Rachmiel -

Horyniec-Zdrój 200 0 200 M Das Portal 200 0 100 100 200 M NOWINY 4 Rathaus HORYNIECKIE 5 Zwierzyniec Kultur- Und Erholungszentrum Torowa

1 Jüdischer Friedhof 2 Kirche Muttergottes Königin von Polen 3 Sportverein Sokół Zwierzyniec Horyniec-Zdrój 200 0 200 m Das Portal www.greenvelo.pl 200 0 100 100 200 m NOWINY 4 Rathaus HORYNIECKIE 5 Zwierzyniec Kultur- und Erholungszentrum Torowa HORYNIECKA Południoworoztoczański 6 Stadtpark POLANKA ZAMOJSKA Besuchen Sie die WWW-Seite www.greenvelo.pl und 7 Kirche des heiligen Johannes Nepomuk PrzemysłowaMyśliwska Wodna Park Krajobrazowy Monopolowa Verwaltungskomplex der Zamojski 1 erfahren Sie, welche Möglichkeiten der Ostpolnische www.greenvelo.pl 8 Cm. Familienfideikommiss Przemysłowa żydowski Sanatoryjna 8 SZCZEBRZESZYN, ZAMOŚĆ 9 „Zwierzyńczyk” Park Radweg bietet. Das Portal ist der größte Reiseführer für (Woiwodschaft Świętokrzyskie) (Woiwodschaft 858 10 Brauerei Zwierzyniec Rolna Dębowa Radfahrer in Ostpolen. Dank ihm werden Sie den Ablauf Umgebung und Gebirge Świętokrzyskie 12. 11 Musealen Bildungszentrum LUBACZÓW (Woiwodschaften Podkarpackie und Świętokrzyskie) und Podkarpackie (Woiwodschaften des Nationalparks Roztocze Leśna der Route sowie den Verlauf anderer Wege in der Umge- San-Tal Untere das und Sandomierz Region 11. 12 Das Haus des Bevollmächtigten HORYNIEC-ZDRÓJ PKP Glinianiec 2 Lutego Karpatenvorland (Woiwodschaft Podkarpackie) (Woiwodschaft Karpatenvorland 10. Myśliwska 867 bung kennen lernen, Sie finden touristische Attraktionen, Roztocze (Woiwodschaften Lubelskie und Podkarpackie) und Lubelskie (Woiwodschaften Roztocze 9. 8 Legionów Cm. Polesien (Woiwodschaft Lubelskie) (Woiwodschaft Polesien 8. Kośc. MB 3 HREBENNE Unterkunft und Restaurants. Vor der Reise können Sie mit Królowej Polski Bug-Tal (Woiwodschaften Podlaskie und Lubelskie) und Podlaskie (Woiwodschaften Bug-Tal 7. Klub AL. PRZYJAŻNI 2 Sportowy 867 Wąska Hilfe des Reiseplaners in einfachen Schritten den eigenen Plan erstellen. Urwälder Białowieska und Knyszyńska (Woiwodschaft Podlaskie) (Woiwodschaft Knyszyńska und Białowieska Urwälder 6. DębowaSłowackiego Sokół Hłaski Leœna Das Tal der Biebrza und Narew (Woiwodschaft Podlaskie) (Woiwodschaft Narew und Biebrza der Tal Das 5. -

142-2019 Yukhnovskyi.Indd

Original Paper Journal of Forest Science, 66, 2020 (6): 252–263 https://doi.org/10.17221/142/2019-JFS Green space trends in small towns of Kyiv region according to EOS Land Viewer – a case study Vasyl Yukhnovskyi1*, Olha Zibtseva2 1Department of Forests Restoration and Meliorations, Forest Institute, National University of Life and Environmental Sciences of Ukraine, Kyiv 2Department of Landscape Architecture and Phytodesign, Forest Institute, National University of Life and Environmental Sciences of Ukraine, Kyiv *Corresponding author: [email protected] Citation: Yukhnovskyi V., Zibtseva O. (2020): Green space trends in small towns of Kyiv region according to EOS Land Viewer – a case study. J. For. Sci., 66: 252–263. Abstract: The state of ecological balance of cities is determined by the analysis of the qualitative composition of green space. The lack of green space inventory in small towns in the Kyiv region has prompted the use of express analysis provided by the EOS Land Viewer platform, which allows obtaining an instantaneous distribution of the urban and suburban territories by a number of vegetative indices and in recent years – by scene classification. The purpose of the study is to determine the current state and dynamics of the ratio of vegetation and built-up cover of the territories of small towns in Kyiv region with establishing the rating of towns by eco-balance of territories. The distribution of the territory of small towns by the most common vegetation index NDVI, as well as by S AVI, which is more suitable for areas with vegetation coverage of less than 30%, has been monitored. -

1 Introduction

State Service of Geodesy, Cartography and Cadastre State Scientific Production Enterprise “Kartographia” TOPONYMIC GUIDELINES For map and other editors For international use Ukraine Kyiv “Kartographia” 2011 TOPONYMIC GUIDELINES FOR MAP AND OTHER EDITORS, FOR INTERNATIONAL USE UKRAINE State Service of Geodesy, Cartography and Cadastre State Scientific Production Enterprise “Kartographia” ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Prepared by Nina Syvak, Valerii Ponomarenko, Olha Khodzinska, Iryna Lakeichuk Scientific Consultant Iryna Rudenko Reviewed by Nataliia Kizilowa Translated by Olha Khodzinska Editor Lesia Veklych ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ © Kartographia, 2011 ISBN 978-966-475-839-7 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Introduction ................................................................ 5 2 The Ukrainian Language............................................ 5 2.1 General Remarks.............................................. 5 2.2 The Ukrainian Alphabet and Romanization of the Ukrainian Alphabet ............................... 6 2.3 Pronunciation of Ukrainian Geographical Names............................................................... 9 2.4 Stress .............................................................. 11 3 Spelling Rules for the Ukrainian Geographical Names....................................................................... 11 4 Spelling of Generic Terms ....................................... 13 5 Place Names in Minority Languages -

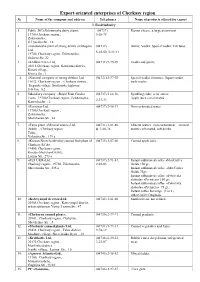

Export-Oriented Enterprises of Cherkasy Region № Name of the Company and Address Telephones Name of Products Offered for Export I

Export-oriented enterprises of Cherkasy region № Name of the company and address Telephones Name of products offered for export I. Food industry 1. Public JSC«Zolotonosha dairy plant», (04737) Rennet cheese, a large assortment 19700,Cherkasy region., 5-26-78 Zolotonosha , G.Lysenko Str., 18 2. «Zolotonosha plant of strong drinks «Zlatogor» (04737) Balms; Vodka; Special vodka; Tinctures. Ltd, 5-23-50, 5-39-41 19700, Cherkasy region, Zolotonosha, Sichova Str, 22 3. «Khlibna Niva» Ltd, (04732) 9-79-69 Vodka and spirits. 20813,Cherkasy region, Kamianka district, Kosari village, Kirova Str., 1 4. «National company of strong drinks» Ltd, (0472) 63-37-70 Special vodka, tinctures, liquers under 19632, Cherkasy region., Cherkasy district , trade marks. Stepanki village, Smilianske highway, 8-th km, б.2 5. Subsidiary company «Royal Fruit Garden (04737) 5-64-26, Sparkling cider, semi-sweet; East», 19700,Cherkasy region, Zolotonosha, Apple juice concentrated 2-27-73 Kanivska Str. , 2 6. «Econiya» Ltd, (04737) 2-16-37 Non-carbonated water. 19700,Cherkasy region , Zolotonosha , Shevchenko Str., 24 7. «Talne plant «Mineral waters»Ltd., (04731) 3-01-88, Mineral waters non-carbonated, mineral 20400, ., Cherkasy region ф. 3-08-36 waters carbonated, soft drinks Talne, Voksalna Str., 139 а 8. «Korsun-Shevchenkivskiy canned fruit plant of (04735) 2-07-60 Canned apple juice Cherkasy RCA», 19400, Cherkasy region., Korsun-Shevchenkivskiy, Lenina Str., 273 а 9. «FES UKR»Ltd, (04737) 2-91-84, Instant sublimated coffee «MacCoffee Cherkasy region., 19700, Zolotonosha, 2-92-03 Gold» 150 gr; Shevchenka Str., 235 а Instant sublimated coffee «MacCoffee Gold» 75gr; Instant sublimated coffee «Petrovska sloboda» «Premiera» 150 gr; Instant sublimated coffee «Petrovska sloboda» «Premiera» 75 gr.; Instant coffee beverage (3 in 1) «MacCoffee Original». -

Textbook on HUUC 2018.Pdf

MINISTRY OF HEALTH CARE OF UKRAINE Kharkiv National Medical University HISTORY OF UKRAINE AND UKRAINIAN CULTURE the textbook for international students by V. Alkov Kharkiv KhNMU 2018 UDC [94:008](477)=111(075.8) A56 Approved by the Academic Council of KhNMU Protocol № 5 of 17.05.2018 Reviewers: T. V. Arzumanova, PhD, associate professor of Kharkiv National University of Construction and Architecture P. V. Yeremieiev, PhD, associate professor of V. N. Karazin Kharkiv National University Alkov V. A56 History of Ukraine and Ukrainian Culture : the textbook for international students. – Kharkiv : KhNMU, 2018. – 146 p. The textbook is intended for the first-year English Medium students of higher educational institutions and a wide range of readers to get substantively acquainted with the complex and centuries-old history and culture of Ukraine. The main attention is drawn to the formation of students’ understanding of historical and cultural processes and regularities inherent for Ukraine in different historical periods. For a better understanding of that, the textbook contains maps and illustrations, as well as original creative questions and tasks aimed at thinking development. UDC [94:008](477)=111(075.8) © Kharkiv National Medical University, 2018 © Alkov V. A., 2018 Contents I Exordium. Ukrainian Lands in Ancient Times 1. General issues 5 2. Primitive society in the lands of modern Ukraine. Greek colonies 7 3. East Slavic Tribes 15 II Princely Era (9th century – 1340-s of 14th century) 1. Kievan Rus as an early feudal state 19 2. Disintegration of Kievan Rus and Galicia-Volhynia Principality 23 3. Development of culture during the Princely Era 26 III Ukrainian Lands under the Power of Poland and Lithuania 1.