Heerlen and Culture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Safety Is the Key to Mission Success

Volume 28, No. 13 NATO Air Base Geilenkirchen 13 July 2012 Photo by Andre Joosten VIP flies with Squadron 2 Col. Ton van Happen, E-3A Component deputy commander (DCOM), poses for a photo with Lt. Gen. H. Wehren in front of an AWACS on July 3 at NATO Air Base Geilenkirchen.60¡ The general65¡ is the newly70¡ appointed75¡ deputy chief80¡ of Defence85¡ for the90¡ Netherlands95¡ (DCHOD)100¡ and is105¡ the primary110¡ advisor to115¡ the Netherlands 120¡ Minister 125¡ of Defence 40¡ for all AWACS issues.UZBEKIS TGeneralAN Wehren flew on a mission sortie with with Colonel van Happen and members of Squadron 2, whose objective was to support a Dutch 4vs8 KAZAKHST AN Fighter Weapons Instructor Training mission. During the flight, the DzungaDCHODr iawas briefed on past,MONGOLIA ongoing and future operations, fleet modernization and the Canadian Almaty withdrawal. He was also briefed on noise relatedBishkek issues such as the Component’s†rŸmqi very successful noise policy,GOBI the economic impact of the NAEWBeijing program to Dalianthe general and Bukhara Oz. Issyk Kul' N local economy, and the need to performTashkent tree maintenance. After his flight,H theA general expressed his appreciation for the Component’s contribution to NATO’s mission. UZBEKISTAN KYRGYZSTAN S Hami Baotou Tianjin Bo Hai N Samarkand E I Turfan Depression Aksu TURKMENISTAN T 35¡ Mashhad ORDOS Shijiazhuang 35¡ Dushanbe Qingdao TAJIKISTAN Yinchuan Yumen Taiyuan T ARIM PENDI YELLOW Sheberghan Mazar-e Sharif N Q I L I SEA CHINA OPERATION H A A N IRAN S S Herat A L T U N H A N o Safety is the key to mission successg H n Qinghai Hu wa Zhengzhou AFGHANIST AN AHotanFGHAN H S H Luoyang Kabul N A Lanzhou Shanghai Farah L A N By E-3A Component Public Affairs safety programsK forU Ntheir respective training and lessons learned from workXi'an dangers and create the safest work H ASSIST u 30¡ Srinagaragencies with the assistance of unit center accidents ina n2011 and 2012. -

Mini-Europe. in These Times of Crisis and These Years of Remembrance Of

"Mini-Europe offers a unique opportunity to experience and see first hand the beauty and diversity of our continent. Europe is a political endeavour which we in the European Parliament fight to defend, but it is also a cultural treasure whose value must be learnt and seen by Europeans and foreigners alike." Martin SCHULZ Martin SCHULZ, Donald TUSK, President of the President of the * * "I said that Europe needs to be big on big things and small on small things. European Parliament. European Council. Well, Mini-Europe is now the only place in the EU where it is allowed to be small on big things !" Jean-Claude JUNCKER "This concept, Europe, will make the common founda- tion of our civilisation clear to all of us and create little by little a link similar to the one with which the nations were forged in the past." Robert Schuman Jean-Claude JUNCKER, Federica MOGHERINI, President of the Commission High Representative of the European Union.* for the Common Foreign and Security Policy.* Thierry MEEÙS Director Mini-Europe Welcome to Mini-Europe. Éducation ASBL In these times of crisis and these years of remembrance of the 1914-18 war, we must not forget that the European Union and the Euro have maintained solidarity between Europeans. A hundred years ago, nationalism and competition between nations led us to war. This guide is an essential help on your trip through The European Union. As Robert Schuman said, you will find out what these people, regions and countries have in common … and what makes each one special. -

Maastricht: a True Star Among Cities

city guide : city 2 : culture 24 : shopping 48 : culinary & out on the town 60 : active in South Limburg 84 : practical information 95 2/3 : city Maastricht: a true star among cities Welcome to Maastricht, one of the oldest cities in the Netherlands – a city that has ripened well with age, like good wine, with complex and lively cultural overtones added over centuries by the Romans, germans and French. this rich cultural palette is the secret behind the city’s attractive- Welcome ness, drawing visitors to the historic city centre If you pass by the most famous and a wealth of museums and festivals – making square in Maastricht, you will each visit a fascinating new experience. undoubtedly notice the fantas- tic and colourful set of figures But Maastricht is also a vibrant makes Maastricht special – in representing the Carnival and contemporary city with a the heart of the South Limburg orchestra ‘Zaate Herremenie.’ rich landscape of upmarket as hill country and nestled in the The Carnival celebration, or well as funky boutiques and a Meuse River Valley. Is it any ‘Vastelaovend’ as it is called wide range of restaurants & wonder that Maastricht is such by the locals, lasts only three cafés serving everything from a great place for a day out, a days, but this trumpet player local dishes, hearty pub food, weekend getaway, or a longer welcomes visitors to the and great selections of beer holiday? Vrijthof all year round. to the very best haute cuisine. Maastricht: a true star And of course its location also among cities. : city / welcome : city / zicht op Maastricht 4/5 compact and pedestrianfriendly A true son discover The centre of Maastricht is compact and easy to explore on of Maastricht Maastricht on foot. -

Packages Paketreisen

Packages Paketreisen Europe ... Benelux überland Ziele überland Destinations überland Reisen ist Paketer und Spezialist für überland Reisen is a package tour operator Gruppenreisen nach Berlin, Deutschland, Benelux - that has specialised in trips for groups to Berlin, seit 1990! Für die Organisation von Klassenfahrten, Germany, and the Benelux countries since 1990. Rund- und Städtereisen, Firmen- und Vereins- Whether you are going on a school trip, round reisen erstellen wir zielgruppengerechte Angebote trip, city tour, or a company or club outing, we are vom individuellen Programmbaustein bis zum happy to put together a tailor-made programme kompletten Arrangement. Dank starker Partner for you ranging from individual activities right im In- und Ausland bietet überland Reisen einen through to an entire itinerary. Thanks to our strong kompletten Incoming Service zu sehr attraktiven partnerships both at home and abroad, überland Preisen an. Reisen can offer a complete incoming service at very attractive prices. uberland Tecklenburg Benelux | Germany . Kampstr. 1 • D-49545 Tecklenburg-Germany • Telefon +49(0)5482-92 98 88 0 • Fax +49(0)5482-92 98 88 10 • [email protected] uberland Berlin Germany | Europe | Klassenfahrten Young Travel . Arndtstr. 34 • D-10965 Berlin-Germany • Telefon +49(0)30-69 53 17-0 • Fax +49(0)30-69 53 17-29 • [email protected] www.ueberland.de Inhalt Content Amsterdam 50 Antwerpen | Antwerp 12 Ardennen | Les Ardennes 42 Herzlich willkommen bei überland ! Welcome to überland 2 Belgien |Belgium 4 überland Service -

Maps -- by Region Or Country -- Eastern Hemisphere -- Europe

G5702 EUROPE. REGIONS, NATURAL FEATURES, ETC. G5702 Alps see G6035+ .B3 Baltic Sea .B4 Baltic Shield .C3 Carpathian Mountains .C6 Coasts/Continental shelf .G4 Genoa, Gulf of .G7 Great Alföld .P9 Pyrenees .R5 Rhine River .S3 Scheldt River .T5 Tisza River 1971 G5722 WESTERN EUROPE. REGIONS, NATURAL G5722 FEATURES, ETC. .A7 Ardennes .A9 Autoroute E10 .F5 Flanders .G3 Gaul .M3 Meuse River 1972 G5741.S BRITISH ISLES. HISTORY G5741.S .S1 General .S2 To 1066 .S3 Medieval period, 1066-1485 .S33 Norman period, 1066-1154 .S35 Plantagenets, 1154-1399 .S37 15th century .S4 Modern period, 1485- .S45 16th century: Tudors, 1485-1603 .S5 17th century: Stuarts, 1603-1714 .S53 Commonwealth and protectorate, 1660-1688 .S54 18th century .S55 19th century .S6 20th century .S65 World War I .S7 World War II 1973 G5742 BRITISH ISLES. GREAT BRITAIN. REGIONS, G5742 NATURAL FEATURES, ETC. .C6 Continental shelf .I6 Irish Sea .N3 National Cycle Network 1974 G5752 ENGLAND. REGIONS, NATURAL FEATURES, ETC. G5752 .A3 Aire River .A42 Akeman Street .A43 Alde River .A7 Arun River .A75 Ashby Canal .A77 Ashdown Forest .A83 Avon, River [Gloucestershire-Avon] .A85 Avon, River [Leicestershire-Gloucestershire] .A87 Axholme, Isle of .A9 Aylesbury, Vale of .B3 Barnstaple Bay .B35 Basingstoke Canal .B36 Bassenthwaite Lake .B38 Baugh Fell .B385 Beachy Head .B386 Belvoir, Vale of .B387 Bere, Forest of .B39 Berkeley, Vale of .B4 Berkshire Downs .B42 Beult, River .B43 Bignor Hill .B44 Birmingham and Fazeley Canal .B45 Black Country .B48 Black Hill .B49 Blackdown Hills .B493 Blackmoor [Moor] .B495 Blackmoor Vale .B5 Bleaklow Hill .B54 Blenheim Park .B6 Bodmin Moor .B64 Border Forest Park .B66 Bourne Valley .B68 Bowland, Forest of .B7 Breckland .B715 Bredon Hill .B717 Brendon Hills .B72 Bridgewater Canal .B723 Bridgwater Bay .B724 Bridlington Bay .B725 Bristol Channel .B73 Broads, The .B76 Brown Clee Hill .B8 Burnham Beeches .B84 Burntwick Island .C34 Cam, River .C37 Cannock Chase .C38 Canvey Island [Island] 1975 G5752 ENGLAND. -

Revitalization by Reconciliation Newspaper

15. Mostra Internazionale di Architettura Eventi Collaterali STRATEGIES FOR TRANSFORMING CROSS-BORDER REGIONS Revitalization by Reconciliation is more than an exhibition. Beyond being a platform for shared knowledge, it is a laboratory for strategic interventions based on an integrated approach for urban development, social cohesion and renewed civic participation. The exhibition invites the public audience to explore how spatial design can challenge a new IBA LEGACY vision for European Regions, by reconciling fragmented territorial layers and historical frames IBA Germany into a revitalized meaningful unity. In that sense the Querini Stampalia Foundation stands as a symbol. As Scarpa’s architecture reworked the existing EUREGION MEUSE-RHINE space, “Revitalization by Reconciliation” composes territories in a comparable way. IN TRANSITION By presenting the Dutch approach and the border IBA Parkstad and indeland as interface, between land and water or between nations, curator Jo Coenen considers that “Reporting from the Front” is the right stage to reflect on COASTAL PERSPECTIVES overcoming constraints of the crisis, thinking beyond the dichotomy of top-down and bottom-up solutions. AND INNOVATIVE The initiative will result into a contribution to the DEVELOPMENTS European Week for Regions and Cities in Bruxelles, in North Holland at the moment the European Commission is looking for efficient models for urban development. The current cross border projects in Netherlands STUDENT are presented in the exhibition supported by INTERNATIONAL an historical overview of the IBA phenomenon (Internationale Bauausstellung). STUDIO EVENTS RECONCILIATION REVITALISATION BY 1 THE ART OF BLENDING Jo Coenen concludes that The ®MIT research programme, during the past few decades with Jo Coenen as scientific we have been subjected to an director, stands at the epicentre unpredicted dynamic process of of the current debate in social and cultural change due architecture and construction. -

EN GUIDE Bonnefantenstraat 2 Map of Each the Netherlands’ CL6 COFFEELOVERS ST

MBD_adv_148x193_2017_2.pdf 1 07-10-16 11:21 COFFEE we love City Guide Maastricht LOVERS coffee 2017 City Guide Maastricht Shop the finest brands, such as Isabel Marant, Longchamp, Furla, Ganni, Hugo Boss, CL1 COFFEELOVERS DOMINICANEN Armani JEANS, Max Mara and many more. In fabulous bookstore Dominikanerskerkstraat 1 We welcome you 7 days a week in our CL2 COFFEELOVERS PLEIN 1992 Maastricht store on Achter het Vleeshuis 26. Urban coffee & lunch Ruiterij 2 CL3 COFFEELOVERS THE ANNEX Coffee lounge & terrace Plein 1992 CL4 COFFEELOVERS AVENUE Coffee in the library (1st floor) Avenue Céramique CL5 COFFEELOVERS UNIVERSITY Students & coffee meeting point EN GUIDE Bonnefantenstraat 2 Map of each The Netherlands’ CL6 COFFEELOVERS ST. PIETER most European city. Neighbourhood coffee corner district, with Glacisweg 26 You can feel it, see it, Must Sees and taste it! ‘17 THE BEST SHOPPING TIPS, RESTAURANTS, AND HIDDEN TREASURES OF MAASTRICHT www.visitmaastricht.nl € 4,95 www.visitmaastricht.nl MAISON BLANCHE DAEL SINCE 1878 Coffee roasters ~ tea packers ~ fresh peanuts www. .nl Wolfstraat 28 ~ www.blanchedael.nl 1 EN VVV Cover 2017 ENG.indd 1 13-12-16 12:17 MBD_adv_148x193_2017_2.pdf 1 07-10-16 11:21 contentCity Guide Maastricht COFFEE we love City Guide Maastricht LOVERS coffee 2017 City Guide Maastricht Shop the finest brands, such as Isabel Marant, Longchamp, Furla, Ganni, Hugo Boss, CL1 COFFEELOVERS DOMINICANEN Armani JEANS, Max Mara and many more. In fabulous bookstore Dominikanerskerkstraat 1 58 We welcome you 7 days a week in our CL2 COFFEELOVERS PLEIN 1992 Maastricht store on Achter het Vleeshuis 26. Urban coffee & lunch Ruiterij 2 CL3 COFFEELOVERS THE ANNEX 48 Coffee lounge & terrace Plein 1992 CL4 COFFEELOVERS AVENUE 132 Coffee in the library (1st floor) DISCOVER Avenue Céramique 14 3 THE CL5 COFFEELOVERS UNIVERSITY Students & coffee meeting point CITY FR GUIDE Bonnefantenstraat 2 Les incon- 34 WyckLa ville la plus CL6 COFFEELOVERS ST. -

Route Finder

> English South Limburg > Adventure > Attractions > Culinary > Culture > Cycling > Going out > Limburg Shop > Marlstone caves Free! > Monuments > Shopping > Walking Route Finder > Wellness Route Finder South Limburg Route Finder South Limburg Sections Walking & Cycling Tourist information in South Limburg > 30-31 Limburg Shop > 4-5 South Limburg Museums, Galleries South Limburg map > 6-7 & Studios > 32-33 > Main office of the Tourist Information South Limburg South Limburg, Attractions & Sights > 34-35 Walramplein 6, Postbus 820 a wonderful region > 8-9 6300 AV Valkenburg aan de Geul Action & Sports > 36-39 Region of castles > 10-12 River recreation > Branch offices of the Marlstone & Caves > 13 on the Meuse > 40 Tourist Information South Limburg Monuments, Churches & Mills Body treatment in South Limburg > 14-23 and Wellness > 41 > Beek > Berg en Terblijt > Bocholtz The South Limburg Tourist Information, > Born > Brunssum > Eijsden > Epen the Maastricht Tourist Information and Parks, Gardens Visiting companies > 42-43 > Eys > Geleen > Gulpen > Heerlen the North and Middle Limburg Tourist & Nature Reserves > 24-27 > Hoensbroek > Kerkrade > Landgraaf Information Services together promote Nightlife > Margraten > Mechelen > Meerssen the province of Limburg as cooperating Walks, City visits & Entertainment > 44-45 > Noorbeek > Nuth > Schin op Geul Tourist Information Services. & Excursions > 28 > Schinnen > Schinveld > Simpelveld Enjoying the good life > Sint Geertruid > Sittard > Stein Shopping > 29 in South Limburg > 46-51 > Vaals > Valkenburg a/d Geul > Vijlen > Voerendaal > Wijlre For more Tourist Information and bookings telephone number 0900-9798 (€ 1 per call) Colofon Coordination, general text South Limburg Survival Limburg, ROCCA, Gulpen; Corbis; can be used within the Netherlands. If you This brochure is a product of the Tourist Information, department of Marketing A ge Pannes Bar, Schin op Geul; Anouk call from abroad, use 0031-43-609 8518. -

FISITA 2014 World Automotive Congress 2–6 June, Maastricht, the Netherlands

FISITA 2014 World Automotive Congress 2–6 June, Maastricht, the Netherlands Intelligent transport to solve our future mobility, safety and environmental challenges Preliminary Programme Welcome Message 4 FISITA 2014 Committees 6 Introducing FISITA & Royal Dutch Society of Engineers 8 FISITA Member Societies 10 FISITA Honorary Committee 12 Programme Overview 14 Executive Track 15 Technical Programme 17 Special Sessions 43 Educators Seminar & Educators Technical Session 46 Student & Young Engineers Programme 48 Exhibition 50 Technical Tours 54 Social Programme 55 Cultural Tours 56 Welcome to Maastricht 60 General Information 62 Registration Information 64 Accommodation 66 The FISITA 2014 World Automotive Congress is organised by Royal Dutch Society of Engineers & FISITA (the International Federation of Automotive Engineering Societies). The Preliminary Programme is published by FISITA (UK) Limited, 30 Percy St, London W1T 2DB, United Kingdom Company Registered in England No. 03572997 Chief Executive – Ian Dickie Advertising – Joey Timmins, +44 (0)20 7299 6637 Design by Darren Cartwright, CJ Media, +44 (0) 1299 861 484 Copyright © 2014 FISITA (UK) Limited 3 Welcome Message Dr. Li Jun FISITA President These topics will be discussed in our diverse line up of Technical Sessions, including sessions focused on Clean and Efficient Engine Technologies, Advanced Safety Technologies, Automotive Human Factors, NVH and New Energy Powertrain. Another exciting topic of focus at this year’s congress will be Autonomous Driving, with both a keynote speech and a session topic devoted to exploring transformational benefits in safety and environmental performance as well as a pathway to a lucrative new market. Our opening keynote address comes from Prof. Dr.-Ing. Ulrich Hackenberg, credited with restructuring technical development at Rolls Royce, developing the concept of the Bentley model and revolutionising vehicle platform strategy for Volkswagen group by developing the innovative Modular Longitudinal Matrix. -

Your Travel Guide

Your travel guide visitzuidlimburg.com #visitzuidlimburg Zuid-Limburg Narrowest part of the Netherlands Westzipfelpunkt Historical River Meuse city centre of Sittard Sittard Hoensbroek Castle Marl caves Cauberg Heerlen Kerkrade Maastricht Columbus, Cube Continium Vrijthof Valkenburg square Heuvelland GaiaZOO (rolling hills) Gulpen Bonnefanten GERMANY Eijsden Vaals museum Aachen Drielandenpunt (tri-border point) BELGIUM 2 #visitzuidlimburg Welcome to Zuid-Limburg Zuid-Limburg is the southernmost and sunniest region of The Netherlands! Zuid-Limburg borders on Germany in the east and on Belgium in the south and west. As the centre of this border triangle, Germany – The Netherlands – Belgium, Zuid-Limburg boasts a boundless diversity in a small area. Its many attractive destinations and sights, make Zuid-Limburg a popular tourism destination. There is something there to suit every traveller, whether young or old, interested in sports or recreational activities. We invite you to relax and unwind, get active and to explore! Just as you like it best. In Your travel guide you will find all the inspiration and information that helps you make the most of your visit. Have fun! 3 Must do’s in Zuid-Limburg Different from the rest Hiking and cycling region of The Netherlands The Zuid-Limburg region is a true To the south, Zuid-Limburg borders on paradise for hikers and cyclists. the foothills of the Ardennes (Belgium), The hilly landscape features old High Fens (Belgium), and Eifel (Germa- sunken lanes, open plateaus and idyllic ny). This gives the region its character, woodlands. Along the way, picturesque which is not typical for the Netherlands villages and authentic towns alternate. -

NAEW&C Force

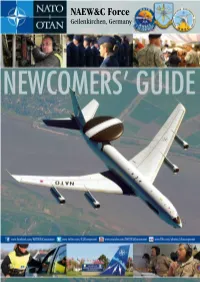

NAEW&C Force Geilenkirchen, Germany Renting furniture... a smart decision! TAX FREE RENTAL & SALESwith monthly down payments www.in-lease.com We provide: furniture, appliances, kitchenware, lighting, linnen, garden furniture. With or without buying option. At home with ease Contact: Marc Hul • [email protected] • T +32 (0)3 238 74 66 • M +32 (0)475 636 022 IL_advert-A4_SHAPE-2018-V2_NEW.indd 1 21/03/2019 09:31 NATO E-3A COMPONENT NEWCOMERS’ GUIDE WELCOME TO NATO AIR BASE Renting furniture... GEILENKIRCHEN, home of the NATO Airborne Early Warning and Control a smart decision! Force Headquarters, the E-3A Component and the Mission Support Engineering Centre. As your E-3A Component Commander, I am excited to welcome you and your families to our team of professional military and civilian Airmen. You are joining a team that has been dedicated to the security of the NATO Alliance for over 37 years, and as part of that legacy, you will be helping ensure our success for years to come. Since 1982, the NATO AWACS program has provided a high-readiness airborne capability to the Supreme Allied TAX Command as part of the NATO Integrated Air and Missile Defense System and beyond, to include operations in Iraq, FREE Afghanistan, Libya, the Balkans, and the United States. You RENTAL should be justifiably proud that your nation has chosen you areas, as well as helpful tips to make your move as easy to be a part of NATO’s leading edge force in demonstrating as possible. Of course, your greatest resources in this & SALESwith monthly alliance air power! exciting and challenging assignment are the multinational down payments www.in-lease.com teammates and friends you will meet in your time here! Our mission of providing responsive Air Battle Management Whether it’s understanding NATO operations or getting We provide: furniture, appliances, for NATO is one that I am very proud of. -

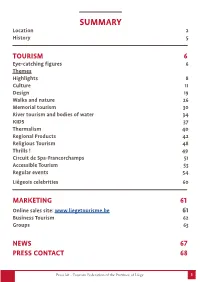

SUMMARY Location 2 History 5

SUMMARY Location 2 History 5 TOURISM 6 Eye-catching figures 6 Themes Highlights 8 Culture 11 Design 19 Walks and nature 26 Memorial tourism 30 River tourism and bodies of water 34 KIDS 37 Thermalism 40 Regional Products 42 Religious Tourism 48 Thrills ! 49 Circuit de Spa-Francorchamps 51 Accessible Tourism 53 Regular events 54 Liégeois celebrities 60 MARKETING 61 Online sales site: www.liegetourisme.be 61 Business Tourism 62 Groups 63 NEWS 67 PRESS CONTACT 68 Press kit - Tourism Federation of the Province of Liège 1 INTRODUCTION Location Liège is situated at the gateway to Ardenne. Its geographic location means that it is exceptionally open to Europe, and a major motorway and rail network reinforces its international calling. Liège is promoted as being the transportation hub of the Meuse- Rhine Euregion. Meuse-Rhine Euregion, which brings together the regions of Liège, Aachen, Hasselt, Heerlen and Maastricht, covers a surface area of 10,500 km and is home to 3.7 million inhabitants. At a dis- tance of just 30 km away from the Nether- lands and 45 km away from Germany, Liège is also ideally located on the London - Brus- sels - Berlin high-speed TGV train route, not forgetting the Thalys link with Paris (barely 2 hours and 20 minutes). Press kit - Tourism Federation of the Province of Liège 2 | Getting to Liège by car A highly comprehensive road and motorway network (E40, E25, E42, E313) makes it very easy to get to Liège by car from the major Belgian and European cities. With its motorway network shaped like a seven-pointed star, Liège features among Europe’s principal communi- cation hubs.