The Guidebook Odyssey - Unearthing the Epic Task of Writing a Guidebook by Michael Adamson

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

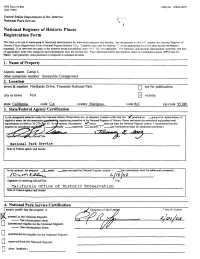

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NPS Form 10-900 OMBNo. 10024-0018 (Oct. 1990) United States Department of the Interior » , • National Park Service V National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determination for individual properties and districts Sec instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" lor 'not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and area of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10- 900A). Use typewriter, word processor or computer to complete all items. 1. Name of Property____________________________________________________ historic name Camp 4 other name/site number Sunnyside Campground__________________________________________ 2. Location_______________________________________________________ street & number Northside Drive, Yosemite National Park |~1 not for publication city or town N/A [_xj vicinity state California code CA county Mariposa code 043 zip code 95389 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this Itjiomination _irquest for determination of eligibility meets the documentationsJand»ds-iJar -

California Road Trip a Climber’S Guide Northern California

Introduction California Road Trip A Climber’s Guide Northern California by Tom Slater and Chris Summit With contributing authors Steve Edwards and Marty Lewis Guidebook layout and design by Tom Slater Maps by Amy Panzardi, Tom Slater, & Marty Lewis MAXIMVS PRESS California Road Trip - North NORTHERN CALIFORNI A Over view Map 199 Cresent City N 101 97 Eureka Goose 299 Lake 5 101 Section 5 Alturas North Coast 29 9 page 376 Redding Red Bluff 395 5 1 101 Chico Section 4 Tahoe Area page 286 5 99 Santa Rosa 80 116 80 Lake Sacramento Tahoe 99 50 12 99 Section 2 88 Yosemite/ 1 116 101 Gold Country 88 page 147 80 12 San 680 Francisco Oakland 580 Modesto Yosemite San 12 0 99 Nat. Park 395 Santa Jose Cruz Merced Section 1 Section 3 Lee San Francisco Vining Southern Sierra Bay Area page 30 Salinas page 227 1 99 6 101 5 Bishop King Fresno City Kings Canyon Nat. Park Sequoia Death Nat. Park Valley 99 Nat. 46 Park 19 0 MartyGraphic Lewis Bakersfiel d 395 17 8 10 California Road Trip - North Table of Contents Foreword......................................12 Sequoia/Kings.Cyn..Overview........113 Moro Rock **** .............................................114 Preface..........................................14 Little Baldy *** .............................................120 Introduction................................16 Chimney Rock **** ......................................123 Buck Rock **.................................................127 Key.to.Stars Shaver.Lake.Overview......................129 Tollhouse Rock *** .......................................130 ***** World Class. Squarenail Rock **.......................................134 **** Excellent destination crag. Dogma Dome * ............................................137 *** Regionally famous, good Courtright Reservoir **** ...........................139 destination. ** Good local crag. SECTION 2N— * Good if passing through. YOSEMITE/GOLD COUntry SECTION 1N— Section.2.Overview..................147. SOUTHERN SIERRA Shuteye Ridge **** ......................................150 So. -

Cómo Entrenar Y Escalar Mejor

R. 5120773 Cómo entrenar y escalar mejor Eric Hörst 796.52 MANUAL RECOMENDADO POR: ESCUELA ESPAÑOLA DE ALTA MONTAÑA Federación Española de Deportes de Montaña y Escalada Ediciones Desnivel DEDICATORIA A mis padres, por 30 años de amor y apoyo y a Jeff Batzer, mi original compañero de entrenamiento cuya increíble forma de escalar -en todas sus variantes- continúa siendo una inspiración. CÓMO ENTRENAR Y ESCALAR MEJOR © Chockstone Press. / Eric J. Hörst, 1994 Título original: Flash Training © Ediciones Desnivel 1ª Edición en castellano: Febrero 1996 Traducción: Gema Redondo Revisión técnica: Tino Núñez Maquetación: Jorge Galán Liquete Las fotos sin créditos pertenecen al autor. Fotos de aprendizaje: Mike McGill y el autor. Imprime: Miram ISBN: 84-87746-64-0 Depósito Legal: M-32.683-1996 Está prohibida la reproducción o almacenamiento total o parcial del libro por cualquier medio: fotográfico, fotocopia, mecánico, reprográfico, óptico, magnético o electrónico sin la autorización expresa y por escrito del titular del © copyright. Ley de la Propiedad Intelectual (22/1987). ADVERTENCIA: LA ESCALADA ES UN DEPORTE EN EL QUE PUEDES RESULTAR SERIAMENTE LESIONADO O INCLUSO MORIR. Éste es un manual técnico para practicar la escalada, un deporte intrínsecamente peligroso; las rutinas y ejercicios descritos son aconsejables sólo para escaladores con un cierto nivel (6a en adelante). Para tu seguridad, no te bastará únicamente con la información contenida en este libro. Tu seguridad física en este deporte depende de tu propio criterio basado en una información competente, tu experiencia, y un buen conocimiento de tu propia capacidad como escalador. No hay nada en la escalada que pueda sustituir al profesor, cosa fácil de encontrar. -

STRANDED, EXCEEDING ABILITIES Colorado, Flatirons Analysis

COLORADO / 35 STRANDED, EXCEEDING ABILITIES Colorado, Flatirons Six members from the Colorado Rescue Dogs and Alpine Rescue Team (MRA), who were on a social climb, met the involved party at the start of the Eyebolt route (5.0- 5.4) of the Third Flatiron in suburban Boulder County. During the usual preclimb chatter, it became obvious that two members of the party had never seen a rope before, much less tied a knot or climbed a rock. The leader (20) did not appear significantly superior in skills. He was wearing a fine commercial harness, carried a rack of “better” carabiners and protection, and had two nearly new kernmantle ropes. After he had tied the other two into the waist loops only of their inadequate home-tied swami belts, we were able to suggest to him that a chased figure eight through the leg loops might be better than an unsaftied bowline. They led off before us. We met them at the first belay point about 45 minutes later (150 feet of 4th class). The leader had led the second pitch; number two was still on the first belay anchor, and number one was stranded and panicking about 5 feet up. Her hard, smooth, crepe soled shoes could not grip the rock. The leader lowered her to the ledge and then we lowered her to the ground, having to instruct her on how to work the gate on her carabiner, etc., through our fixed rope. During this evacuation, one of her shoes broke completely in two. She finished the descent barefoot. -

Cleveland (Cleve) Mccarty

CLEVELAND (CLEVE) MCCARTY. Born 1933. TRANSCRIPT of OH 1336V A-B. This interview was recorded on June 8, 2005, for the Maria Rogers Oral History Program. The interviewer is Robyn Crispe. The interview is also available in video format, filmed by Liz McCutcheon. The interview was transcribed by Catherine Jopling and Carol Jordan. NOTE: The interviewer’s questions and comments appear in parentheses. Added material appears in brackets. ABSTRACT: Cleveland McCarty, a pioneer in rock climbing and co-author of High Over Boulder, talks about his love for climbing (both rock climbing and mountaineering) since his boyhood days in Boulder. He shares stories of some of his more memorable climbs along the Front Range and elsewhere. [A]. 00:00 (This is Robyn Crispe. I’m interviewing for the Maria Rogers Oral History Program of the Carnegie Branch Library for Local History. The date is Wednesday, June 8, 2005. The narrator is Cleveland McCarty, and we’re at his home at 315 Arapahoe in Boulder, Colorado.) (So, thank you for having this interview with us, and I’ll start by asking when and where were you born.) I’m a native, born in Denver, Colorado, and when—1933. (When did you move to Boulder?—What brought you here?) I went to school here, so that would’ve been in the ‘50s—‘53 or so. And then I went in the Air Force. I went to dental school in St. Louis at Washington University and then the Air Force, and back to Denver for a year, and finally in ‘66 bought a home here, started a practice. -

Climbing.Com Helmets 317.Pdf

HEAD TRAUMA IS AMONG THE MOST FEARED AND CATASTROPHIC INJURIES IN CLIMBING. SO WHy aren’T MORE ROCK CLIMBERS WEARING HELMETS? By Dougald MacDonald Photography by Ben Fullerton ¬No-Brainer 40 | AUGUST 2013 CLIMBING.COM | 41 BetH RoddeN didN’t expect tRouBle oN tHe trad route, the long, easy east face of the is more dangerous: If you venture above mostly in the lower extremities. In 2009, Second Flatiron in Boulder, Colorado. base camp on Annapurna, you’ve got about the American Journal of Preventive Medi- ceNtRal pillaR of fReNzy Near the top, her partner asked if she’d a 1 in 25 chance of dying. By contrast, fa- cine published a study by Nicolas Nelson oN yosemite’s middle like to lead a short step. Barnes fell part- talities in rock climbing and bouldering are and Lara McKenzie of U.S. Consumer Prod- catHedRal Rock. afteR all, tHe 33-yeaR-old way up the pitch, popping out her naively very uncommon. Statistically, rock climbing uct Safety Commission data on climbers placed pro, and tumbled down the slab. is nowhere near as dangerous as the main- admitted to emergency rooms. Injuries to She sprained both ankles, strained a knee stream media (or your mom) would believe. the lower extremities accounted for nearly supeRstaR Had fRee climBed tHe and thumb, and chomped a big chunk out An average of about 30 climbers of all half of the climber ER visits between 1990 of her tongue. Before she came to a stop, disciplines die each year in the United and 2007, with ankles bearing the brunt of Nose of el cap she smacked the side of her head just States, from falling, rockfall, or any other the damage. -

Library List Oct 2016 by Author.Pdf

A. Arnold-Brown. 1962. Unfolding character. The impact of Gordonstoun. A. Christensen (editor). 1987. Wilderness first aid. A. F. Mummery. 1895. My Climbs in the Alps and Caucasus. A. F. Mummery. 1974. My Climbs in the Alps and Caucasus. A. Harvard and T. Thompson. 1974. Mountain of Storms. A. K. Lobeck. 1939. Geomorphology: an introduction to the study of landscapes. A.H. Griffin. 1974. Long days in the hills. A.O. Wheeler. 1905. Selkirk Range, The. A.O. Wheeler. 1912. Selkirk Mountains, The. A guide for mountain pilgrims and climbers. A.P. Coleman. 1911. Canadian Rockies, The: new and old trails. A.W. Moore and E.H. Stevens (editors). 1939. Alps in 1864, The. Adrian and Alan Burgess. 1998. Burgess book of lies, The. Adrian and Alan Burgess. 2007. Brotherhood of the rope. The biography of Charles Houston. Advance Rock Climbing Committee, MIT Outing Club. 1956. Fundamentals of rock climbing. Al Burgess and Jim Palmer. 1983. Everest Canada. The ultimate challenge. Alan Blackshaw. 1965. Mountaineering. From hill walking to alpine climbing. Alan Blackshaw. 1973. Mountaineering. Alan Kane. 1999. Scrambles in the Canadian Rockies. Alastair Borthwick. 1989. Always a Little Further: a classic tale of camping, hiking and climbing in Scotland in the thirties. Alexander Mackenzie Trail Association. 1989 - 1996. Newsletter. Alfred Wills. 1937. Wandering Among the High Alps. Alice Purdey, John Halliday, and David and Mary Macaree . 2014. 109 Walks in British Columbia’s Lower Mainland. Allen Steck, Steve Roper, and David Harris (editors). 1999. Ascent. The climbing experience in word and image. Alpine Club of Canada, Vancouver Section. 1959-2012. -

DE BANADE VÄG FÖR KLÄTTRINGEN Valtou R N E Nche, Italy H Erv É B Armasse

#159 september 2013 Pris: 50 sek. ETT KLÄTTER- FÖRBUND BLIR TILL STOLT 40-ÅRING JUNIORERNAS ROADTRIP PUMAN TOG EM-GULD MÖT ”LG” OCH 16 ANDRA PROFILER DE BANADE VÄG FÖR KLÄTTRINGEN VALTOU R N E NCHE, ITALY H ERV É B ARMASSE # THERMOBALL NEVER ONE PLACE. ALWAYS ONE JACKET. NEVER STOP ™ EXPLORING THERMOBALL™ HOODIE ULTRALIGHT WARMTH IN ALL CONDITIONS THERMOBALL™ IS THE BREAKTHROUGH ALTERNATIVE TO DOWN THAT PROVIDES PHOTO: Damiano Levati UNCOMPROMISING WARMTH EVEN WHEN WET. DISCOVER MORE AT THENORTHFACE.COM TNF_F13_Thermoball_Bergsport_420x285_Sve.indd 1 19/07/13 14.52 VALTOU R N E NCHE, ITALY H ERV É B ARMASSE # THERMOBALL NEVER ONE PLACE. ALWAYS ONE JACKET. NEVER STOP ™ EXPLORING THERMOBALL™ HOODIE ULTRALIGHT WARMTH IN ALL CONDITIONS THERMOBALL™ IS THE BREAKTHROUGH ALTERNATIVE TO DOWN THAT PROVIDES PHOTO: Damiano Levati UNCOMPROMISING WARMTH EVEN WHEN WET. DISCOVER MORE AT THENORTHFACE.COM TNF_F13_Thermoball_Bergsport_420x285_Sve.indd 1 19/07/13 14.52 INNEHÅLL SEPTEMBER 2013 6 Förbundsnyheter 12 Ett klätterförbund blir till 18 Boulderingens intåg 20 Intervjun: Gudmund Söderin 22 Profilerna 34 Intervjun: Lars-Göran ”LG” Johansson 36 Nytt från klubbarna 39 Juniorernas roadtrip gav EM-guld 42 Toppenklättring i Georgien Omslaget till historiens första Bergsport! Foto: Annika Ringstedt 4 BERGSPorT #159 · SEPTEMBER 2013 JSM Foto: Martin Argus Bouldering 5-6 oktober 2013 Solna klätterklubb och Svenska klätterförbundet bjuder in till Svenska PJÄS: DE TVÅ juniormästerskapen i bouldering 2013. Foto: Martin Argus JSMTävlingen äger rum 5-6 oktober på REDAKTÖRERNA Klättercentret i Uppsala. Scen 2 Bouldering 5-6 oktober 2013 Plats: Eva framför datorn i söder OBS! Tävlingen flyttad till och Annika framför datorn SolnaKlättercentret klätterklubb och Svenska i Uppsala. -

Anna Kacperczyk University of Lodz, Poland Between Individual and Collective Actions

Anna Kacperczyk University of Lodz, Poland Between Individual and Collective Actions: The Introduction of Innovations in the Social World of Climbing DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.18778/1733-8077.15.2.08 Abstract This article, which is based upon the findings of a seven-year research project concerning the social world of climbing, discusses climbing as an organized social practice that possesses a strong historical dimen- sion and collective character. It examines the relation between individual participants and that social world as a whole, and it accepts that an individual’s personal life may be inscribed in the development and formation of that world in two ways. These are 1) a given social world imposes the behavioral pat- terns, normative rules, institutional schemes of actions, and careers upon participants that characterize their identities and actions; and 2) the actions of an individual participant trigger significant change in that world. I am particularly interested in those unique situations in which when a participant induces a change that affects a given social world (or a sub-world) as a whole, and discuss two examples of this relation, namely, the history of designing and creating climbing equipment, and setting new standards of climbing performance. Briefly stated, innovative solutions are born in conjunction with particular climb- ing actions that are either promoted or hindered depending on whether or not the vision of the primary activity associated with those solutions was accepted by the majority of participants. The dynamics and transformations of the social world in question thus rely upon the activities of exceptional individuals who, as pioneers, innovators, and visionaries, attain mastery in performing the primary activity of that world and set new standards of performance for others. -

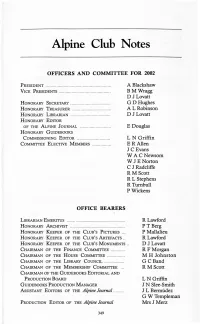

Alpine Club Notes

Alpine Club Notes OFFICERS AND COMMITTEE FOR 2002 PRESIDENT .. A Blackshaw VICE PRESIDENTS . BMWragg DJ Lovatt HONORARY SECRETARY . GD Hughes HONORARY TREASURER .. AL Robinson HONORARY LIBRARIAN .. D JLovatt HONORARY EDITOR OF THE ALPINE JOURNAL .. E Douglas HONORARY GUIDEBOOKS COMMISSIONING EDITOR . LN Griffin COMMITTEE ELECTIVE MEMBERS .. E RAllen JC Evans W ACNewsom W JE Norton CJ Radcliffe RM Scott RL Stephens R Tumbull P Wickens OFFICE BEARERS LIBRARIAN EMERITUS .. RLawford HONORARY ARCHIVIST .. .. PT Berg HONORARY KEEPER OF THE CLUB'S PICTURES . P Mallalieu HONORARY KEEPER OF THE CLUB'S ARTEFACTS .. RLawford HONORARY KEEPER OF THE CLUB'S MONUMENTS .. DJ Lovatt CHAIRMAN OF THE FINANCE COMMITTEE RFMorgan CHAIRMAN OF THE HOUSE COMMITTEE .. MH Johnston CHAIRMAN OF THE LIBRARY COUNCIL .. GCBand CHAIRMAN OF THE MEMBERSHIP COMMITTEE RM Scott CHAIRMAN OF THE GUIDEBOOKS EDITORIAL AND PRODUCTION BOARD LN Griffin GUIDEBOOKS PRODUCTION MANAGER JN Slee-Smith ASSISTANT EDITORS OF THE Alpine Journal JL Bermudez GW Templeman PRODUCTION EDITOR OF THE Alpine Journal Mrs JMerz 349 350 THE ALPINE J OURN AL 2002 ASSISTANT HONORARY SECRETARIES: ANNuAL WINTER DINNER . MHJohnston LECTURES .. MWHDay MEETS . JC Evans MEMBERSHIP . RM Scot! TRUSTEES .. MFBaker JG RHarding S NBeare HONORARY SOLICITOR . PG C Sanders AUDITORS . PKF ASSISTANT SECRETARY (ADMINISTRATION) .. Sheila Harrison ALPINE CLIMBING GROUP PRESIDENT .. D Wilkinson HONORARY SECRETARY . RA Ruddle GENERAL, INFORMAL, AND CLIMBING MEETINGS 2001 9 January General Meeting: Stevan Jackson, British -

Climbers' Guidebooks 551

2 INDEX GENERAL BOOKS: 1- 530 FICTION: 531 - 542 CAVING: 543 - 547 SKIING: 548 - 550 GUIDEBOOKS (ENGLISH LANGUAGE): 551 - 823 GUIDEBOOKS (FOREIGN LANGUAGE): 824 - 855 WALKING/TREKKING GUIDES: 856 - 866 FOREIGN LANGUAGE BOOKS: 867 - 877 JOURNALS 878 - 947 MAGAZINES: 948 - 964 PHOTOGRAPHS: 965 - 967 1. Abraham, A.P: BEAUTIFUL LAKELAND: Abraham, Keswick; 1920: (2nd) edition. Hardback, 52 pages, 32 monogravure plates (including one on front cover) by G.P Abraham of Keswick, 28.5cm. Head of spine lightly bumped with a 1cm joint split reglued (darkened) at head and base, corner tips also reglued; foxing and browning mainly confined to outer page-edges and endpapers, overall a VG presentable copy. General commentary on the Lake District; enhanced with fine Abraham photographs of the period: £10.00 2. Abraham, G.D: BRITISH MOUNTAIN CLIMBS: Mills & Boon; 1937: 4th edition. Pages xvi + 448, 18 plates, 21 outline drawings, 17.5cm. Complete, but pages 49-64 bound out of sequence. Previous owner’s bookplate inside front board; faint water stain lower corner of frontispiece and a slight touch of wrinkling in vicinity; surface glaze dull (8x8cm) on lower rear corner of rear board; slight foxing top outer edge of pages; but otherwise a Near Fine very clean copy in (dust wrapper condition - spine age- darkened, slightly rubbed and tiny loss at base) d/w now protected in a loose plastic sleeve. Primarily a guidebook but also useful for the history of early British climbing: £25.00 3. Abraham, G.D: BRITISH MOUNTAIN CLIMBS: Mills & Boon; 1945 5th edition: Pages xvi + 448, 18 plates, 21outline drawings, 18cm. -

“Yosemite Is a Pile.” “The Bouldering Is Just A

Contents Preface 9 Ahwahnee Boulders, West 94 Indian Creek 98 Introduction 11 Lower Yosemite Falls 104 Swan Slab Boulders 108 Logistics 11 Camp 4, Overview 112 Bouldering History 22 Camp 4, Columbia Grades and Stars 29 Boulders 114 Yosemite’s Best Lists 31 Camp 4, East 116 Overview Maps 32 Camp 4, Center 122 How to Use this Guide 34 Camp 4, West 128 Topo Legend 34 The Crystals 136 Areas Yabo Boulder 139 The Bachar Boulder 140 Turtle Dome 35 Wood Yard 142 Bridalveil Boulders 36 The Wave 146 Lower Cathedral 38 Intersection Boulders 148 Gunsight Boulders 40 Knobby Wall 148 Cathedral Boulders 42 Appendix Lost Boulders 50 Candyland 54 More From SuperTopo 150 The Presidential Boulder 60 About the Author 152 Sentinel Boulders 62 Problems by Grade 153 Chicken Boulder 68 Index 157 Housekeeping 70 Curry Village 76 Happy Isles 82 Horse Trail Boulders 84 Ahwahnee Boulders, East 88 Ahwahnee Boulders, Central 90 5 FOR CURRENT ROUTE INFORMATION, VISIT WWW.SUPERTOPO.COM Warning! Climbing and bouldering are inherently dangerous sports in which severe injuries or death may occur. Relying on the information in this book may increase the danger. When climbing you can only rely on your skill, training, experience, and conditioning. If you have any doubts as to your ability to safely climb any route in this guide, do not try it. This book is neither a professional climbing instructor nor a substitute for one. It is not an instructional book. Do not use it as one. It contains information that is nothing more than a compilation of opinions about bouldering in Yosemite Valley.