Mariner Venus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Space Impact of the Euro Crisis 50 Years After Mariner 2: Exploration at a Crossroads

0827_SPN_DOM_00_019_00 (READ ONLY) 8/24/2012 11:39 AM Page 19 www.spacenews.com SPACENEWS 19 August27, 2012 TheSpaceImpact of the Euro Crisis < ROBBIN LAIRD and HARALD MALMGREN > he European sovereign debt crisis Europe will now be challenged in the ing to hide the reality of European bank of the savings of millions of European is not simply abump in historical form of rollbacks of the many inter- weaknesses. The main reason is that eu- citizens. Tprogress; it is the end of aperiod twined strands of integration, fraying rozone economies are far more bank- European leaders are also attempt- of historyand acritical point in Euro- what has been an intricate but incom- dependent than economies like those in ing to initiate amore comprehensive fis- pean and global transition in the 21st plete tapestry. It is questionable whether the United States or United Kingdom, cal union, with new decision-making century. Europe will be able to prevent stalling of where substantial nonbank financing al- mechanisms that transfer sovereignty in The confluence of several trend lines the integration process in the face of ternatives exist for the corporate sector. parallel with the new banking union. We — the unification of Germany,the end widening gaps among the interests of In the eurozone, banks are the fi- do not believe that any of the eurozone of the Soviet Union, the collapse of the each nation and even within each nation. nancial markets; in the U.S., banks are governments are ready for such apoliti- Berlin Wall, the expansion of NATO, Since the birth of the euro, the but one segment of amultifaceted fi- cal transition in which citizens in each the expansion of the European Union French and Germans were in the lead in nancial market. -

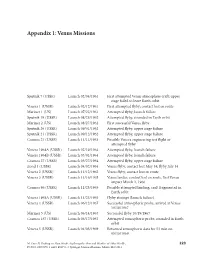

Appendix 1: Venus Missions

Appendix 1: Venus Missions Sputnik 7 (USSR) Launch 02/04/1961 First attempted Venus atmosphere craft; upper stage failed to leave Earth orbit Venera 1 (USSR) Launch 02/12/1961 First attempted flyby; contact lost en route Mariner 1 (US) Launch 07/22/1961 Attempted flyby; launch failure Sputnik 19 (USSR) Launch 08/25/1962 Attempted flyby, stranded in Earth orbit Mariner 2 (US) Launch 08/27/1962 First successful Venus flyby Sputnik 20 (USSR) Launch 09/01/1962 Attempted flyby, upper stage failure Sputnik 21 (USSR) Launch 09/12/1962 Attempted flyby, upper stage failure Cosmos 21 (USSR) Launch 11/11/1963 Possible Venera engineering test flight or attempted flyby Venera 1964A (USSR) Launch 02/19/1964 Attempted flyby, launch failure Venera 1964B (USSR) Launch 03/01/1964 Attempted flyby, launch failure Cosmos 27 (USSR) Launch 03/27/1964 Attempted flyby, upper stage failure Zond 1 (USSR) Launch 04/02/1964 Venus flyby, contact lost May 14; flyby July 14 Venera 2 (USSR) Launch 11/12/1965 Venus flyby, contact lost en route Venera 3 (USSR) Launch 11/16/1965 Venus lander, contact lost en route, first Venus impact March 1, 1966 Cosmos 96 (USSR) Launch 11/23/1965 Possible attempted landing, craft fragmented in Earth orbit Venera 1965A (USSR) Launch 11/23/1965 Flyby attempt (launch failure) Venera 4 (USSR) Launch 06/12/1967 Successful atmospheric probe, arrived at Venus 10/18/1967 Mariner 5 (US) Launch 06/14/1967 Successful flyby 10/19/1967 Cosmos 167 (USSR) Launch 06/17/1967 Attempted atmospheric probe, stranded in Earth orbit Venera 5 (USSR) Launch 01/05/1969 Returned atmospheric data for 53 min on 05/16/1969 M. -

Mariner to Mercury, Venus and Mars

NASA Facts National Aeronautics and Space Administration Jet Propulsion Laboratory California Institute of Technology Pasadena, CA 91109 Mariner to Mercury, Venus and Mars Between 1962 and late 1973, NASA’s Jet carry a host of scientific instruments. Some of the Propulsion Laboratory designed and built 10 space- instruments, such as cameras, would need to be point- craft named Mariner to explore the inner solar system ed at the target body it was studying. Other instru- -- visiting the planets Venus, Mars and Mercury for ments were non-directional and studied phenomena the first time, and returning to Venus and Mars for such as magnetic fields and charged particles. JPL additional close observations. The final mission in the engineers proposed to make the Mariners “three-axis- series, Mariner 10, flew past Venus before going on to stabilized,” meaning that unlike other space probes encounter Mercury, after which it returned to Mercury they would not spin. for a total of three flybys. The next-to-last, Mariner Each of the Mariner projects was designed to have 9, became the first ever to orbit another planet when two spacecraft launched on separate rockets, in case it rached Mars for about a year of mapping and mea- of difficulties with the nearly untried launch vehicles. surement. Mariner 1, Mariner 3, and Mariner 8 were in fact lost The Mariners were all relatively small robotic during launch, but their backups were successful. No explorers, each launched on an Atlas rocket with Mariners were lost in later flight to their destination either an Agena or Centaur upper-stage booster, and planets or before completing their scientific missions. -

(50000) Quaoar, See Quaoar (90377) Sedna, See Sedna 1992 QB1 267

Index (50000) Quaoar, see Quaoar Apollo Mission Science Reports 114 (90377) Sedna, see Sedna Apollo samples 114, 115, 122, 1992 QB1 267, 268 ap-value, 3-hour, conversion from Kp 10 1996 TL66 268 arcade, post-eruptive 24–26 1998 WW31 274 Archimedian spiral 11 2000 CR105 269 Arecibo observatory 63 2000 OO67 277 Ariel, carbon dioxide ice 256–257 2003 EL61 270, 271, 273, 274, 275, 286, astrometric detection, of extrasolar planets – mass 273 190 – satellites 273 Atlas 230, 242, 244 – water ice 273 Bartels, Julius 4, 8 2003 UB313 269, 270, 271–272, 274, 286 – methane 271–272 Becquerel, Antoine Henry 3 – orbital parameters 271 Biermann, Ludwig 5 – satellite 272 biomass, from chemolithoautotrophs, on Earth 169 – spectroscopic studies 271 –, – on Mars 169 2005 FY 269, 270, 272–273, 286 9 bombardment, late heavy 68, 70, 71, 77, 78 – atmosphere 273 Borealis basin 68, 71, 72 – methane 272–273 ‘Brown Dwarf Desert’ 181, 188 – orbital parameters 272 brown dwarfs, deuterium-burning limit 181 51 Pegasi b 179, 185 – formation 181 Alfvén, Hannes 11 Callisto 197, 198, 199, 200, 204, 205, 206, ALH84001 (martian meteorite) 160 207, 211, 213 Amalthea 198, 199, 200, 204–205, 206, 207 – accretion 206, 207 – bright crater 199 – compared with Ganymede 204, 207 – density 205 – composition 204 – discovery by Barnard 205 – geology 213 – discovery of icy nature 200 – ice thickness 204 – evidence for icy composition 205 – internal structure 197, 198, 204 – internal structure 198 – multi-ringed impact basins 205, 211 – orbit 205 – partial differentiation 200, 204, 206, -

March 21–25, 2016

FORTY-SEVENTH LUNAR AND PLANETARY SCIENCE CONFERENCE PROGRAM OF TECHNICAL SESSIONS MARCH 21–25, 2016 The Woodlands Waterway Marriott Hotel and Convention Center The Woodlands, Texas INSTITUTIONAL SUPPORT Universities Space Research Association Lunar and Planetary Institute National Aeronautics and Space Administration CONFERENCE CO-CHAIRS Stephen Mackwell, Lunar and Planetary Institute Eileen Stansbery, NASA Johnson Space Center PROGRAM COMMITTEE CHAIRS David Draper, NASA Johnson Space Center Walter Kiefer, Lunar and Planetary Institute PROGRAM COMMITTEE P. Doug Archer, NASA Johnson Space Center Nicolas LeCorvec, Lunar and Planetary Institute Katherine Bermingham, University of Maryland Yo Matsubara, Smithsonian Institute Janice Bishop, SETI and NASA Ames Research Center Francis McCubbin, NASA Johnson Space Center Jeremy Boyce, University of California, Los Angeles Andrew Needham, Carnegie Institution of Washington Lisa Danielson, NASA Johnson Space Center Lan-Anh Nguyen, NASA Johnson Space Center Deepak Dhingra, University of Idaho Paul Niles, NASA Johnson Space Center Stephen Elardo, Carnegie Institution of Washington Dorothy Oehler, NASA Johnson Space Center Marc Fries, NASA Johnson Space Center D. Alex Patthoff, Jet Propulsion Laboratory Cyrena Goodrich, Lunar and Planetary Institute Elizabeth Rampe, Aerodyne Industries, Jacobs JETS at John Gruener, NASA Johnson Space Center NASA Johnson Space Center Justin Hagerty, U.S. Geological Survey Carol Raymond, Jet Propulsion Laboratory Lindsay Hays, Jet Propulsion Laboratory Paul Schenk, -

Impact Melt Emplacement on Mercury

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 7-24-2018 2:00 PM Impact Melt Emplacement on Mercury Jeffrey Daniels The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Neish, Catherine D. The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Geology A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Master of Science © Jeffrey Daniels 2018 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Geology Commons, Physical Processes Commons, and the The Sun and the Solar System Commons Recommended Citation Daniels, Jeffrey, "Impact Melt Emplacement on Mercury" (2018). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 5657. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/5657 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract Impact cratering is an abrupt, spectacular process that occurs on any world with a solid surface. On Earth, these craters are easily eroded or destroyed through endogenic processes. The Moon and Mercury, however, lack a significant atmosphere, meaning craters on these worlds remain intact longer, geologically. In this thesis, remote-sensing techniques were used to investigate impact melt emplacement about Mercury’s fresh, complex craters. For complex lunar craters, impact melt is preferentially ejected from the lowest rim elevation, implying topographic control. On Venus, impact melt is preferentially ejected downrange from the impact site, implying impactor-direction control. Mercury, despite its heavily-cratered surface, trends more like Venus than like the Moon. -

N€WS 'RELEASE NATIONAL AERONAUTICS and SPACE Admln ISTRATION 400 MARYLAND AVENUE, SW, WASHINGTON 25, D.C

https://ntrs.nasa.gov/search.jsp?R=19630002483 2020-03-11T16:50:02+00:00Z b " N€WS 'RELEASE NATIONAL AERONAUTICS AND SPACE ADMlN ISTRATION 400 MARYLAND AVENUE, SW, WASHINGTON 25, D.C. TELEPHONES WORTH 2-4155-WORTH. 3-1110 RELEASE NO. 62-182 MARINER SPACECRAFT Mariner 2, the second of a series of spacecraft designed for planetary exploration,- will be launched within a few days (no earlier than August 17) from the Atlantic Missile Range, Cape Canaveral, Florida, by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Mariner 1, launched at 4:21 a.m. (EST) on July 22, 1962 from AMR, was destroyed by the Range Safety Officer after about 290 seconds of flight because of a deviation from the planned flight path. Measures have been taken to correct the difficulties experienced in the Mariner 1 launch. These measures include a more rigorous checkout of the Atlas rate beacon and revision of the data editing equation. The data editing equation Is designed as a guard against acceptance of faulty databy the ground guidance equipment. The Mariner 2 spacecraft and its mission are identical to the first Mariner. Mariner 2 will carry six experiments. Two of these instruments, infrared and microwave radiometers, will make measurements at close range as Mariner 2 flys by Venus and communicate this in€ormation over an interplanetary distance of 36 million miles, Four other experiments on the spacecraft -- a magnetometer, ion chamber and particle flux detector, cosmic dust detector and solar plasma spectrometer -- will gather Information on interplantetary phenomena during the trip to Venus and in the vicinity of the planet. -

Complete List of Contents

Complete List of Contents Volume 1 Cape Canaveral and the Kennedy Space Center ......213 Publisher’s Note ......................................................... vii Chandra X-Ray Observatory ....................................223 Introduction ................................................................. ix Clementine Mission to the Moon .............................229 Preface to the Third Edition ..................................... xiii Commercial Crewed vehicles ..................................235 Contributors ............................................................. xvii Compton Gamma Ray Observatory .........................240 List of Abbreviations ................................................. xxi Cooperation in Space: U.S. and Russian .................247 Complete List of Contents .................................... xxxiii Dawn Mission ..........................................................254 Deep Impact .............................................................259 Air Traffic Control Satellites ........................................1 Deep Space Network ................................................264 Amateur Radio Satellites .............................................6 Delta Launch Vehicles .............................................271 Ames Research Center ...............................................12 Dynamics Explorers .................................................279 Ansari X Prize ............................................................19 Early-Warning Satellites ..........................................284 -

Evolution and Geochemistry of the Martian Crust: Integrating Mission Datasets

Seventh International Conference on Mars 3179.pdf EVOLUTION AND GEOCHEMISTRY OF THE MARTIAN CRUST: INTEGRATING MISSION DATASETS. B. C. Hahn1 and S. M. McLennan1, 1Department of Geosciences, Stony Brook University, Stony Brook, NY, 11794-2100 ([email protected], [email protected]). Introduction: The Martian crust is an important the Odyssey GRS has an inherently low resolving ca- geochemical reservoir. It is the only portion of the pacity with a spatially large footprint and thus cannot planet surveyed by broad-scale remote sensing obser- be used effectively for fine-scale regional analysis. vations (beginning with the Mariner program through Additionally, element abundance maps are subject to the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter) or by in situ lander considerable smoothing and auto-correlation effects experiments (from the Viking missions through the due to element correction factors, the large footprint Mars Exploration Rovers). Mars experienced a unique and necessary data processing [6, 10]. This too, limits mechanism for crustal emplacement, resurfacing, and GRS analysis to areally-large regional or global stud- recycling [1] – different from the continuous plate tec- ies. For cross-instrument data analysis (e.g., comparing tonic regime of Earth or the episodic, widespread ba- GRS elemental abundances to TES mineralogies or salt flooding of Venus. USGS relative apparent surface ages), higher- Further, it is well-established that crusts of the in- resolution global datasets (e.g., TES mineralogical ner planets and rocky satellites become substantially maps) must be smoothed to GRS’s lower-resolution. enriched in a suite of geochemically important ele- The Mars Exploration Rovers, Spirit and Oppor- ments during early differentiation and further evolu- tunity, have each traveled several kilometers across the tion [2, 3]. -

Phil Liebrecht Assistant Deputy Associate Administrator and Deputy Program Manager Space Communications and Navigation NASA HQ

Phil Liebrecht Assistant Deputy Associate Administrator and Deputy Program Manager Space Communications and Navigation NASA HQ Meeting the Communications and Navigation Needs of Space missions since 1957 “Keeping the Universe Connected” Public University of Navarra, 2010 [email protected] 1 Operations and Communications Customers 2 Space Operations 101 Relation Between Space Segment, Ground System, and Data Users* Ground System Command Commands Requests Spacecraft and Payload Support • Mission Planning Telemetry • Flight Operations • Flight Dynamics • Perf. Assess., Trending & Archiving Space Data Users • Anomaly Support Segment Data Relay and Level (S/C) Mission Zero Data Processing Mission Data Data • Space-to-ground Comm. • Data Capture • Data Processing • Network Management • Data Distribution • Quick Look * Based on Wertz and Wiley; Space Mission Analysis and Design 3 Communications Theory- Basic Concepts Transmitter and Receiver must use the same language Noise causes interference a) Figures it – no errors (Identify and quantify) b) Figures it – corrects Must be loud enough ENERGY! c) Figures it – incorrectly (message in error) d) Cannot figure- recognizes E L an error T M E XP AIN L E e) Cannot figure- ? TRANSMITTER Distance weakens the sound RECEIVER (calculate the loss) CHANNEL Has to correctly interpret the message - the most difficult job The fundamental problem of communications is that of reproducing at one point either exactly or approximately a message selected at another point. 4 Functional - End to End Process -

Deep Space Chronicle Deep Space Chronicle: a Chronology of Deep Space and Planetary Probes, 1958–2000 | Asifa

dsc_cover (Converted)-1 8/6/02 10:33 AM Page 1 Deep Space Chronicle Deep Space Chronicle: A Chronology ofDeep Space and Planetary Probes, 1958–2000 |Asif A.Siddiqi National Aeronautics and Space Administration NASA SP-2002-4524 A Chronology of Deep Space and Planetary Probes 1958–2000 Asif A. Siddiqi NASA SP-2002-4524 Monographs in Aerospace History Number 24 dsc_cover (Converted)-1 8/6/02 10:33 AM Page 2 Cover photo: A montage of planetary images taken by Mariner 10, the Mars Global Surveyor Orbiter, Voyager 1, and Voyager 2, all managed by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California. Included (from top to bottom) are images of Mercury, Venus, Earth (and Moon), Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune. The inner planets (Mercury, Venus, Earth and its Moon, and Mars) and the outer planets (Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune) are roughly to scale to each other. NASA SP-2002-4524 Deep Space Chronicle A Chronology of Deep Space and Planetary Probes 1958–2000 ASIF A. SIDDIQI Monographs in Aerospace History Number 24 June 2002 National Aeronautics and Space Administration Office of External Relations NASA History Office Washington, DC 20546-0001 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Siddiqi, Asif A., 1966 Deep space chronicle: a chronology of deep space and planetary probes, 1958-2000 / by Asif A. Siddiqi. p.cm. – (Monographs in aerospace history; no. 24) (NASA SP; 2002-4524) Includes bibliographical references and index. 1. Space flight—History—20th century. I. Title. II. Series. III. NASA SP; 4524 TL 790.S53 2002 629.4’1’0904—dc21 2001044012 Table of Contents Foreword by Roger D. -

NASA and Planetary Exploration

**EU5 Chap 2(263-300) 2/20/03 1:16 PM Page 263 Chapter Two NASA and Planetary Exploration by Amy Paige Snyder Prelude to NASA’s Planetary Exploration Program Four and a half billion years ago, a rotating cloud of gaseous and dusty material on the fringes of the Milky Way galaxy flattened into a disk, forming a star from the inner- most matter. Collisions among dust particles orbiting the newly-formed star, which humans call the Sun, formed kilometer-sized bodies called planetesimals which in turn aggregated to form the present-day planets.1 On the third planet from the Sun, several billions of years of evolution gave rise to a species of living beings equipped with the intel- lectual capacity to speculate about the nature of the heavens above them. Long before the era of interplanetary travel using robotic spacecraft, Greeks observing the night skies with their eyes alone noticed that five objects above failed to move with the other pinpoints of light, and thus named them planets, for “wan- derers.”2 For the next six thousand years, humans living in regions of the Mediterranean and Europe strove to make sense of the physical characteristics of the enigmatic planets.3 Building on the work of the Babylonians, Chaldeans, and Hellenistic Greeks who had developed mathematical methods to predict planetary motion, Claudius Ptolemy of Alexandria put forth a theory in the second century A.D. that the planets moved in small circles, or epicycles, around a larger circle centered on Earth.4 Only partially explaining the planets’ motions, this theory dominated until Nicolaus Copernicus of present-day Poland became dissatisfied with the inadequacies of epicycle theory in the mid-sixteenth century; a more logical explanation of the observed motions, he found, was to consider the Sun the pivot of planetary orbits.5 1.