North Yorkshire Police

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BMJ Open Is Committed to Open Peer Review. As Part of This Commitment We Make the Peer Review History of Every Article We Publish Publicly Available

BMJ Open: first published as 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019312 on 27 March 2018. Downloaded from BMJ Open is committed to open peer review. As part of this commitment we make the peer review history of every article we publish publicly available. When an article is published we post the peer reviewers’ comments and the authors’ responses online. We also post the versions of the paper that were used during peer review. These are the versions that the peer review comments apply to. The versions of the paper that follow are the versions that were submitted during the peer review process. They are not the versions of record or the final published versions. They should not be cited or distributed as the published version of this manuscript. BMJ Open is an open access journal and the full, final, typeset and author-corrected version of record of the manuscript is available on our site with no access controls, subscription charges or pay-per-view fees (http://bmjopen.bmj.com). If you have any questions on BMJ Open’s open peer review process please email [email protected] http://bmjopen.bmj.com/ on September 26, 2021 by guest. Protected copyright. BMJ Open BMJ Open: first published as 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019312 on 27 March 2018. Downloaded from Inter-agency collaboration models for people with mental health problems in contact with the police: a systematic scoping review ForJournal: peerBMJ Open review only Manuscript ID bmjopen-2017-019312 Article Type: Research Date Submitted by the Author: 24-Aug-2017 Complete List of Authors: Parker, Adwoa; -

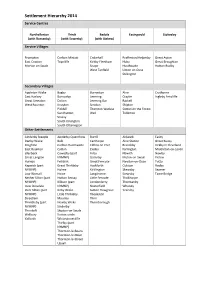

LDF05 Settlement Hierarchy (IPGN) 2014

Settlement Hierarchy 2014 Service Centres Northallerton Thirsk Bedale Easingwold Stokesley (with Romanby) (with Sowerby) (with Aiskew) Service Villages Brompton Carlton Miniott Crakehall Brafferton/Helperby Great Ayton East Cowton Topcliffe Kirkby Fleetham Huby Great Broughton Morton on Swale Snape Husthwaite Hutton Rudby West Tanfield Linton on Ouse Stillington Secondary Villages Appleton Wiske Bagby Burneston Alne Crathorne East Harlsey Borrowby Leeming Crayke Ingleby Arncliffe Great Smeaton Dalton Leeming Bar Raskelf West Rounton Knayton Scruton Shipton Pickhill Thornton Watlass Sutton on the Forest Sandhutton Well Tollerton Sessay South Kilvington South Otterington Other Settlements Ainderby Steeple Ainderby Quernhow Burrill Aldwark Easby Danby Wiske Balk Carthorpe Alne Station Great Busby Deighton Carlton Husthwaite Clifton on Yore Brandsby Kirkby in Cleveland East Rounton Catton Exelby Farlington Middleton-on-Leven Ellerbeck Cowesby (part Firby Flawith Newby Great Langton NYMNP) Gatenby Myton-on-Swale Picton Hornby Felixkirk Great Fencote Newton-on-Ouse Potto Kepwick (part Great Thirkleby Hackforth Oulston Rudby NYMNP) Holme Kirklington Skewsby Seamer Low Worsall Howe Langthorne Stearsby Tame Bridge Nether Silton (part Hutton Sessay Little Fencote Tholthorpe NYMNP) Kilburn (part Londonderry Thormanby Over Dinsdale NYMNP) Nosterfield Whenby Over Silton (part Kirby Wiske Sutton Howgrave Yearsley NYMNP) Little Thirkleby Theakston Streetlam Maunby Thirn Thimbleby (part Newby Wiske Thornborough NYMNP) Sinderby Thrintoft Skipton-on-Swale Welbury Sutton under Yafforth Whitestonecliffe Thirlby (part NYMNP) Thornton-le-Beans Thornton-le-Moor Thornton-le-Street Upsall . -

Download This

Decision Notice Template Part 1 uncontrolled copy when printed OFFICE OF POLICE AND CRIME COMMISSIONER FOR NORTH YORKSHIRE DECISION NOTICE – PART 1 RECORD OF DECISION MADE BY THE COMMISSIONER Decision Notice Number/Date (//2017) Title/Description: Re -locate the fall -back control room facility to Harrogate Police Station Executive Summary and Recommendation: This paper proposes to locate the fall -back facility of the force control room to Harrogate police station, in the event of a critical incident in York. The fall-back facility is currently located at police headquarters at Newby Wiske, but the site is being sold. Moving the facility to Harrogate ensures the right resilience is in place to guarantee North Yorkshire Police can continue to provide a telephone service to the public of North Yorkshire should the control room in York no longer be able to function. The North Yorkshire Police FCR delivers a highly professional and dedicated service 24 hours a day, seven days a week. The FCR provides the essential link with the public in handling emergency and non- emergency calls and are directly involved in managing incidents and deploying officers and resources where they are most needed. In the event of the FCR not being available the FCR fall back facility is immediately deployed. This could be due to technical, power and building issues, or an environmental incident such as flooding. Plans to vacate the Newby Wiske site also make this decision notice necessary. Recommendation: To approve the replacement of the existing Force Control Room (FCR) fall back facility with a new FCR fall back facility at Harrogate Police Station and the requisite funding to deliver this proposal. -

Parish: Newby Wiske Committee Date: Thursday 10Th January 2019

Parish: Newby Wiske Committee date: Thursday 10th January 2019 Ward: Morton on Swale Officer dealing: Miss Charlotte Cornforth th 8 Target date: Friday 11 January 2019 18/01179/FUL Demolition of bungalow and construction of three detached dwellings and garages, alterations to existing access and provision of additional vehicle accesses At Marden, Newby Wiske For Mr & Mrs J Burgess This application is referred to Planning Committee as the application is a departure from the Development Plan 1.0 SITE, CONTEXT AND PROPOSAL 1.1 The application site relates to the curtilage of an existing detached dwelling known as Marden, set in a relatively large plot fronting West View to the south of the village of Newby Wiske. Marden is set back within the site and at a 45-degree angle to West View. 1.2 The dwelling and associated driveway occupy the northern part of the site with the remainder of the site laid out as garden, which is mainly laid to grass with trees adjacent to some boundaries. 1.3 There are three trees within the application site that are the subject of Tree Preservation Orders. The one in the north-west corner is a lime tree and two on the southern boundary are birch trees. No works are proposed to these trees. 1.4 The application site extends to 0.37 hectares and is bound by the existing garden curtilages of Well House to the north and Weighbridge Cottage to the south. To the east, the site is bounded by Riverside Farm comprising of large agricultural buildings and associated hardstanding areas situated immediately to the rear of the site. -

(Electoral Changes) Order 2000

545297100128-09-00 23:35:58 Pag Table: STATIN PPSysB Unit: PAG1 STATUTORY INSTRUMENTS 2000 No. 2600 LOCAL GOVERNMENT, ENGLAND The District of Hambleton (Electoral Changes) Order 2000 Made ----- 22nd September 2000 Coming into force in accordance with article 1(2) Whereas the Local Government Commission for England, acting pursuant to section 15(4) of the Local Government Act 1992(a), has submitted to the Secretary of State a report dated November 1999 on its review of the district of Hambleton together with its recommendations: And whereas the Secretary of State has decided to give effect to those recommendations: Now, therefore, the Secretary of State, in exercise of the powers conferred on him by sections 17(b) and 26 of the Local Government Act 1992, and of all other powers enabling him in that behalf, hereby makes the following Order: Citation, commencement and interpretation 1.—(1) This Order may be cited as the District of Hambleton (Electoral Changes) Order 2000. (2) This Order shall come into force— (a) for the purposes of proceedings preliminary or relating to any election to be held on 1st May 2003, on 10th October 2002; (b) for all other purposes, on 1st May 2003. (3) In this Order— “district” means the district of Hambleton; “existing”, in relation to a ward, means the ward as it exists on the date this Order is made; any reference to the map is a reference to the map prepared by the Department of the Environment, Transport and the Regions marked “Map of the District of Hambleton (Electoral Changes) Order 2000”, and deposited in accordance with regulation 27 of the Local Government Changes for England Regulations 1994(c); and any reference to a numbered sheet is a reference to the sheet of the map which bears that number. -

Areas Designated As 'Rural' for Right to Buy Purposes

Areas designated as 'Rural' for right to buy purposes Region District Designated areas Date designated East Rutland the parishes of Ashwell, Ayston, Barleythorpe, Barrow, 17 March Midlands Barrowden, Beaumont Chase, Belton, Bisbrooke, Braunston, 2004 Brooke, Burley, Caldecott, Clipsham, Cottesmore, Edith SI 2004/418 Weston, Egleton, Empingham, Essendine, Exton, Glaston, Great Casterton, Greetham, Gunthorpe, Hambelton, Horn, Ketton, Langham, Leighfield, Little Casterton, Lyddington, Lyndon, Manton, Market Overton, Martinsthorpe, Morcott, Normanton, North Luffenham, Pickworth, Pilton, Preston, Ridlington, Ryhall, Seaton, South Luffenham, Stoke Dry, Stretton, Teigh, Thistleton, Thorpe by Water, Tickencote, Tinwell, Tixover, Wardley, Whissendine, Whitwell, Wing. East of North Norfolk the whole district, with the exception of the parishes of 15 February England Cromer, Fakenham, Holt, North Walsham and Sheringham 1982 SI 1982/21 East of Kings Lynn and the parishes of Anmer, Bagthorpe with Barmer, Barton 17 March England West Norfolk Bendish, Barwick, Bawsey, Bircham, Boughton, Brancaster, 2004 Burnham Market, Burnham Norton, Burnham Overy, SI 2004/418 Burnham Thorpe, Castle Acre, Castle Rising, Choseley, Clenchwarton, Congham, Crimplesham, Denver, Docking, Downham West, East Rudham, East Walton, East Winch, Emneth, Feltwell, Fincham, Flitcham cum Appleton, Fordham, Fring, Gayton, Great Massingham, Grimston, Harpley, Hilgay, Hillington, Hockwold-Cum-Wilton, Holme- Next-The-Sea, Houghton, Ingoldisthorpe, Leziate, Little Massingham, Marham, Marshland -

Yorkshire Swale Flood History 2013

Yorkshire Swale flood history 2013 Sources The greater part of the information for the River Swale comes from a comprehensive PhD thesis by Hugh Bowen Willliams to the University of Leeds in 1957.He in turn has derived his information from newspaper reports, diaries, local topographic descriptions, minutes of Local Authority and Highway Board and, further back in time, from Quarter Sessions bridge accounts. The information is supplemented by various conversations which Williams had with farmers who owned land adjacent to the river. Where possible the height of the flood at the nearest cross- section of the place referred to in the notes is given. This has either been levelled or estimated from the available data. Together with the level above Ordnance Datum (feet) and the section in question there is given (in brackets) the height of the flood above normal water level. Information is also included from the neighbouring dales (mainly Wensleydale and Teesdale) as this gives some indication of conditions in Swaledale. Williams indicates that this is by no means a complete list, but probably contains most of the major floods in the last 200 years, together with some of the smaller ones in the last 70 years. Date and Rainfall Description sources 11 Sep 1673 Spate carried away dwelling house at Brompton-on-Swale. Burnsell Bridge on the Wharfe was washed away. North Riding Selseth Bridge in the Parish of Ranbaldkirke became ruinous by reason of the late great storm. Quarter Sessions (NRQS) ? Jul 1682 Late Brompton Bridge by the late great floods has fallen down. NRQS Speight(1891) Bridge at Brompton-on-Swale was damaged. -

Superficial Deposits

Mineral Resource Information in Support of National, Regional and Local Planning: North Yorkshire (comprising North Yorkshire, Yorkshire Dales and North York Moors National Parks and City of York) Commissioned Report CR/04/228N BRITISH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY COMMISSIONED REPORT CR/04/228N Mineral Resource Information in Support of National, Regional and Local Planning: North Yorkshire (comprising North Yorkshire, Yorkshire Dales and North York Moors National Parks and City of York) D J Harrison, P J Henney, D Minchin, F M McEvoy, D G Cameron, S F Hobbs, D J Evans, G K Lott, E L Ball and D E Highley The National Grid and other Ordnance Survey data are used with the permission of the This report accompanies the two 1:100 000 scale maps: Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. North Yorkshire (comprising North Yorkshire, Yorkshire Ordnance Survey licence number GD 272191/2006 Dales and North York Moors National Parks and City of York). Key words North Yorkshire; mineral resources; mineral planning Front cover Coldstones Quarry, Carboniferous limestones, view to southwest. North Yorkshire Bibliographical reference Harrison, D J, Henney, P J, Minchin, D, McEvoy, F M, Cameron, D G, Hobbs, S F, Evans, D J, Lott, G K, Ball, E L, and Highley, D E. 2006. Mineral Resource Information in Support of National, Regional and Local Planning: North Yorkshire (comprising North Yorkshire, Yorkshire Dales and North York Moors National Parks and City of York). British Geological Survey Commissioned Report, CR/04/228N. 24pp © Crown Copyright 2006 Keyworth, Nottingham British Geological Survey 2006 BRITISH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY The full range of Survey publications is available Keyworth, Nottingham NG12 5GG from the BGS Sales Desks at Nottingham and Edinburgh; see contact details below or shop online 0115-936 3241 Fax 0115-936 at www.thebgs.co.uk 3488 e-mail: [email protected] The London Information Office maintains a www.bgs.ac.uk reference collection of BGS publications including Shop online at: www.thebgs.co.uk maps for consultation. -

Rose Cottage, Maunby, Thirsk, YO7 4HA Guide Price £259,000

Rose Cottage, Maunby, Thirsk, YO7 4HA Guide price £259,000 www.joplings.com A double fronted detached cottage requiring some updating but with great potential. Located just outside the village of Maunby and with good outside space the property has beautiful far reaching views towards the Hambleton Hills. Accommodation comprises: rear porch, utility/cloakroom, inner hall, cellar, lounge, kitchen open to dining room, three bedrooms and bathroom. Gravelled area to rear allowing parking for several vehicles and caravan. Lawns to front and side, chicken run and outside store and single garage. CHAIN FREE. www.joplings.com LOCATION front. Radiator. Recessed lighting. OUTSIDE From the cross roads at South Otterington, travel KITCHEN 9'6" x 7'5" (2.90m x 2.26m) towards Newby Wiske, past the primary school REAR AREA UPVC window to the rear. Cream base and wall and church and over the little bridge. Turn left on Metal gate from roadway with concrete entrance. units with co-ordinating work surfaces and tiled the corner and continue to the T junction before Gravelled parking area providing parking for splashbacks. One and a half bowl stainless steel entering the village of Maunby. Left at this several vehicles and suitable for a caravan. Brick sink and drainer with mixer tap. Integrated junction and the property is located on the left and tile outbuilding. Chicken run area. Oil tank. electric oven and hob. Space for fridge/freezer. hand side after a quarter of a mile. Recessed lighting. Step down to Dining Area. FRONT Timber fencing to side with hand gate providing REAR PORCH AREA FIRST FLOOR A lean to porch with back door and windows to a secure garden mainly laid to lawn and side and rear. -

Mr Paul Vayro 10 Beechfield, South Otterington, North Yorkshire, DL7 9JJ

Mr Paul Vayro 10 Beechfield, South Otterington, North Yorkshire, DL7 9JJ. Date: 20th November 2017 F.A.O. Diane Parsons North Yorkshire Police & Crime Commission c/o County Hall, Racecourse Lane, Northallerton, North Yorkshire, DL7 8AD. Dear Sirs RE: Sale of Newby Wiske Hall to PGL Travel Ltd I write again regarding the above planned sale to PGL, after attending last Thursdays NYPCC public Q & A forum in York, I am even more disgusted, with NYPCC who are after all supposed to uphold and represent the moral fibre of our society. Following the points made by Mr David Stockport, you would have thought that at least there would have been an acceptance of the points made; instead the Chairman was so indignant to the fact, that someone should dare to suggest that a public body should show even a modicum of moral fibre, in the respect of the Paradise Papers, and the massive negative effect these schemes have on Public Finances and Services, instead the response by the Chairman was, its nothing to do with us, so let’s move on. I repeat, this company are so heavily and extensively involved in a scheme to avoid paying tax in the UK, they receive tax handouts for listed buildings, significant Government subsidies for assisted places (This would be perfectly acceptable if they paid their full taxes to the UK Government), only then to operate a tax avoidance scheme, meaning we, the British tax payer, would be helping them pay even less tax, which could be used to support ALL OUR UNDERFUNDED PUBLIC SERVICES including the POLICE. -

Maunby, Newby Wiske and South Otterington Parish Council

Maunby, Newby Wiske and South Otterington Parish Council Minutes of the Parish Council meeting held at 7.30pm on Thursday 22nd November at the Village Hall, South Otterington Present: Councillors I. Glover (Chairman), K. Bowe, M. Harland, K. Holliday, T. Brett, C. Newton, V. Gillson, County Councillor B. Baker and District Councillor B. Phillips. Item Parish Council Meeting Minutes Action 1. Apologies: Councillor A. Shore Chairman, Iain Glover informed the meeting that Nicola Bowe is off sick. Carol Bowe acting as Temporary Clerk. 2. Minutes of Last Meeting Approval of minutes of last meeting on 18/10/2018 - Proposed Celia Newton. Seconded Vanessa Gilson. 3. Open Forum Ten minutes allocated for public consultation Pat Ovard asked about grit box. Bob Baker seen email to say it is on its way. 4. Matters arising from previous minutes Chairman, Iain Glover asked for letter of thanks to be sent to P H K Steveney and wish him well. a. Newby Wiske Hall – Update – K. Bowe - All action group documents are on portal. Awaiting response from applicant. Peter Jones informed AECOM document not on portal for full application. Lot of training activity on site - Police dogs, firearms, drones, and RSPCA the latest. 129 Associated members of Action Group. Planning Committee Site visit expected to be early January. b. South Otterington Village Signs – Update – Iain Quote £480 plus VAT for one sign. Additional £80 for Yorkshire Rose plus VAT. Fitting £95. Bob Baker – T-l-B quote from firm in Birmingham. Get more prices and ideas. On Agenda for next meeting. c. Report back regarding Defibrillator - Update – V. -

(Designated Rural Areas in the North East) Order 1997

Status: This is the original version (as it was originally made). This item of legislation is currently only available in its original format. STATUTORY INSTRUMENTS 1997 No. 624 HOUSING, ENGLAND AND WALES The Housing (Right to Acquire or Enfranchise) (Designated Rural Areas in the North East) Order 1997 Made - - - - 5th March 1997 Laid before Parliament 7th March 1997 Coming into force - - 1st April 1997 The Secretary of State for the Environment, as respects England, in exercise of the powers conferred upon him by section 17 of the Housing Act 1996(1) and section 1AA(3)(a) of the Leasehold Reform Act 1967(2) and of all other powers enabling him in that behalf, hereby makes the following Order— Citation and commencement 1. This Order may be cited as the Housing (Right to Acquire or Enfranchise) (Designated Rural Areas in the North East) Order 1997 and shall come into force on 1st April 1997. Designated rural areas 2. The following areas shall be designated rural areas for the purposes of section 17 of the Housing Act 1996 (the right to acquire) and section 1AA(3)(a) of the Leasehold Reform Act 1967 (additional right to enfranchise)— (a) the parishes in the districts of the East Riding of Yorkshire, Hartlepool, Middlesborough, North East Lincolnshire, North Lincolnshire, Redcar and Cleveland and Stockton-on-Tees specified in Parts I, II, III, IV, V, VI and VII of Schedule 1 to this Order and in the counties of Durham, Northumberland, North Yorkshire, South Yorkshire, Tyne and Wear and West Yorkshire specified in Parts VIII, IX, X, XI,