Little Magazines Suzanne W

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ezra Pound His Metric and Poetry Books by Ezra Pound

EZRA POUND HIS METRIC AND POETRY BOOKS BY EZRA POUND PROVENÇA, being poems selected from Personae, Exultations, and Canzoniere. (Small, Maynard, Boston, 1910) THE SPIRIT OF ROMANCE: An attempt to define somewhat the charm of the pre-renaissance literature of Latin-Europe. (Dent, London, 1910; and Dutton, New York) THE SONNETS AND BALLATE OF GUIDO CAVALCANTI. (Small, Maynard, Boston, 1912) RIPOSTES. (Swift, London, 1912; and Mathews, London, 1913) DES IMAGISTES: An anthology of the Imagists, Ezra Pound, Aldington, Amy Lowell, Ford Maddox Hueffer, and others GAUDIER-BRZESKA: A memoir. (John Lane, London and New York, 1916) NOH: A study of the Classical Stage of Japan with Ernest Fenollosa. (Alfred A. Knopf, New York, 1917; and Macmillan, London, 1917) LUSTRA with Earlier Poems. (Alfred A. Knopf, New York, 1917) PAVANNES AHD DIVISIONS. (Prose. In preparation: Alfred A. Knopf, New York) EZRA POUND HIS METRIC AND POETRY I "All talk on modern poetry, by people who know," wrote Mr. Carl Sandburg in _Poetry_, "ends with dragging in Ezra Pound somewhere. He may be named only to be cursed as wanton and mocker, poseur, trifler and vagrant. Or he may be classed as filling a niche today like that of Keats in a preceding epoch. The point is, he will be mentioned." This is a simple statement of fact. But though Mr. Pound is well known, even having been the victim of interviews for Sunday papers, it does not follow that his work is thoroughly known. There are twenty people who have their opinion of him for every one who has read his writings with any care. -

A MEDIUM for MODERNISM: BRITISH POETRY and AMERICAN AUDIENCES April 1997-August 1997

A MEDIUM FOR MODERNISM: BRITISH POETRY AND AMERICAN AUDIENCES April 1997-August 1997 CASE 1 1. Photograph of Harriet Monroe. 1914. Archival Photographic Files Harriet Monroe (1860-1936) was born in Chicago and pursued a career as a journalist, art critic, and poet. In 1889 she wrote the verse for the opening of the Auditorium Theater, and in 1893 she was commissioned to compose the dedicatory ode for the World’s Columbian Exposition. Monroe’s difficulties finding publishers and readers for her work led her to establish Poetry: A Magazine of Verse to publish and encourage appreciation for the best new writing. 2. Joan Fitzgerald (b. 1930). Bronze head of Ezra Pound. Venice, 1963. On Loan from Richard G. Stern This portrait head was made from life by the American artist Joan Fitzgerald in the winter and spring of 1963. Pound was then living in Venice, where Fitzgerald had moved to take advantage of a foundry which cast her work. Fitzgerald made another, somewhat more abstract, head of Pound, which is in the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C. Pound preferred this version, now in the collection of Richard G. Stern. Pound’s last years were lived in the political shadows cast by his indictment for treason because of the broadcasts he made from Italy during the war years. Pound was returned to the United States in 1945; he was declared unfit to stand trial on grounds of insanity and confined to St. Elizabeth’s Hospital for thirteen years. Stern’s novel Stitch (1965) contains a fictional account of some of these events. -

Orpheu Et Al. Modernism, Women, and the War

Orpheu et al. Modernism, Women, and the War M. Irene Ramalho-Santos* Keywords Little magazines, Poetry, Modernism, The Great War, Society, Sexual mores. Abstract The article takes off from Orpheu, the little magazine at the origin of Portuguese modernism, to reflect, from a comparative perspective, on the development of modernist poetry in the context of the Great War and the social changes evolving during the first decades of the twentieth century on both sides of the Atlantic. Palavras-chave “Little magazines,” Poesia, Modernismo, A Grande Guerra, Sociedade, Costumes sexuais. Resumo O artigo parte de Orpheu, a revista que dá origem ao modernismo português, para reflectir, numa perspectiva comparada, soBre o desenvolvimento da poesia modernista no contexto da Grande Guerra e das mudanças sociais emergentes nas primeiras décadas do século XX dos dois lados do Atlântico. * Universidade de CoimBra; University of Wisconsin-Madison. Ramalho Santos Orpheu et al. It is frequently repeated in the relevant scholarship that Western literary and artistic modernism started in little magazines.1 The useful online Modernist Journals Project (Brown University / Tulsa University), dealing so far only with American and British magazines, uses as its epigraph the much quoted phrase: “modernism began in the magazines”, see SCHOLES and WULFMAN (2010) and BROOKER and THACKER (2009-2013). With two issues published in 1915 and a third one stopped that same year in the galley proofs for lack of funding, the Portuguese little magazine Orpheu inaugurated modernism in Portugal pretty much at the same time as all the other major little magazines in Europe and the United States. This is interesting, given the proverbial belatedness of Portuguese accomplishments, and no less interesting the fact that, like everywhere else, Orpheu was followed, in Portugal as well, By a number of other little magazines. -

Modernism from Right to Left: Wallace Stevens, the Thirties, and Radicalism

Syracuse University SURFACE The Courier Libraries Spring 1992 Modernism from Right to Left: Wallace Stevens, the Thirties, and Radicalism Alan Filres University of Pennsylvania Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/libassoc Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Filres, Alan, "Modernism from Right to Left: Wallace Stevens, the Thirties, and Radicalism" (1992). The Courier. 293. https://surface.syr.edu/libassoc/293 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Libraries at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Courier by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SYRACUSE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY AS SOC lATE S COURIER VOLUME XXVII, NUMBER 1, SPRING 1992 SYRACUSE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY ASSOCIATES COURIER VOLUME XXVII NUMBER ONE SPRING 1992 Modernism from Right to Left: Wallace Stevens, the Thirties, and Radicalism By Alan Filreis, Associate Professor ofEnglish, 3 University ofPennsylvania Adam Badeau's "The Story ofthe Merrimac and the Monitor" By Robert]. Schneller,Jr., Historian, 25 Naval Historical Center A Marcel Breuer House Project of1938-1939 By Isabelle Hyman, Professor ofFine Arts, 55 New York University Traveler to Arcadia: Margaret Bourke-White in Italy, 1943-1944 By Randall I. Bond, Art Librarian, 85 Syracuse University Library The Punctator's World: A Discursion (Part Seven) By Gwen G. Robinson, Editor, Syracuse University 111 Library Associates Courier News ofthe Syracuse University Library and the Library Associates 159 Modernism from Right to Left: Wallace Stevens, the Thirties, and Radicalism BY ALAN FILREIS Author's note: In writing the bookfrom which thefollowing essay is ab stracted, I need have gone no further than the George Arents Research Li brary. -

Edited by Harriet Monroe

VOL. VIII NO. II Edited by Harriet Monroe MAY 1916 Baldur—Holidays—Finis Allen Upward 55 May in the City .... Max Michelson 63 The Newcomers — Love-Lyric — Midnight — The Willow Tree—Storm—The Red Light—In the Park—A Hymn to Night. To a Golden-Crowned Thrush . Richard Hunt 68 Sheila Eileen—Carnage ...... Antoinette DeCoursey Patterson 69 Indiana—An Old Song Daphne Kieffer Thompson 70 Forgiveness .... Charles L. O'Donnell 72 Sketches in Color Maxwell Bodenheim 73 Columns of Evening—Happiness—Suffering—A Man to a Dead Woman—The Window-Washers—The Department Store Pyrotechnics I-III ..... Amy Lowell 76 To a Flower Suzette Herter 77 A Little Girl I-XIII .... Mary Aldis 78 Editorial Comment 85 Down East Reviews 90 Chicago Granite—The Independents—Two Belgian Poets Our Contemporaries 103 A New School of Poetry—The Critic's Sense of Humor Notes 107 Copyright 1916 by Harriet Monroe. All rights reserved. 543 CASS STREET, CHICAGO $1.50 PER YEAR SINGLE NUMBERS, 15 CENTS Published monthly by Ralph Fletcher Seymour, 1025 Fine Arts Building, Chicago. Entered as second-class matter at Postoffice, Chicago VOL. VIII No. II MAY, 1916 BALDUR OLD loves, old griefs, the burthen of old songs That Time, who changes all things, cannot change : Eternal themes! Ah, who shall dare to join The sad procession of the kings of song— Irrevocable names, that sucked the dregs Of sorrow from the broken honeycomb Of fellowship?—or brush the tears that hang Bright as ungathered dewdrops on a briar? Death hallows all; but who will bear with me To breathe a more heartrending -

M OBAL IMTERPBETEB9S APPROACH to SELECTED

An oral interpreter's approach to selected poems by E. E. Cummings Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Holmes, Susanne Stanford, 1941- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 07/10/2021 02:44:40 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/318940 m OBAL IMTERPBETEB9 S APPROACH TO SELECTED POEMS BY E, E. CUMMINGS "by Susanne Stanford Holmes A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF SPEECH In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS t- In The Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 19 6 4 STATEMENT BY AUTHOR This thesis has been submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for an advanced degree at The University of Arizona and is deposited in the University Library to be made available to borrowers under rules of the Library. Brief quotations from this thesis are allowable with out special permission, provided that accurate acknowledgment of source is made. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this manuscript in whole or in part may be granted by the head of the major department or the Dean of the Graduate College when in his judgment the proposed use of the material is in the interests of scholar ship. In all other instances, however, permission must be obtained from the author. -

The “Objectivists”: a Website Dedicated to the “Objectivist” Poets by Steel Wagstaff a Dissertation Submitted in Partial

The “Objectivists”: A Website Dedicated to the “Objectivist” Poets By Steel Wagstaff A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (English) at the UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN‐MADISON 2018 Date of final oral examination: 5/4/2018 The dissertation is approved by the following members of the Final Oral Committee: Lynn Keller, Professor, English Tim Yu, Associate Professor, English Mark Vareschi, Assistant Professor, English David Pavelich, Director of Special Collections, UW-Madison Libraries © Copyright by Steel Wagstaff 2018 Original portions of this project licensed under a CC BY-SA 4.0 license. All Louis Zukofsky materials copyright © Musical Observations, Inc. Used by permission. i TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements ..................................................................................... vi Abstract ................................................................................................... vii Introduction ............................................................................................... 1 The Lives ................................................................................................ 31 Who were the “Objectivists”? .............................................................................................................................. 31 Core “Objectivists” .............................................................................................................................................. 31 The Formation of the “Objectivist” -

Introduction: the Lives of William Carlos Williams

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-09515-1 - The Cambridge Companion To William Carlos Williams Edited by Christopher Macgowan Excerpt More information 1 CHRISTOPHER MACGOWAN Introduction: the lives of William Carlos Williams William Carlos Williams might have led the life of a small-town doctor – one whose career spanned some important advances in medicine and whose practice was impacted by two world wars, a deadly influenza epidemic, and a depression so severe that many of his patients could not afford to pay him – ending with a few years of retirement from medicine after success- fully handing over his practice. Williams did lead this life. But at the same time he published more than forty books, and was part of a New York avant- garde that included such figures as Marcel Duchamp, Alfred Stieglitz, Wallace Stevens, and Marianne Moore. He knew Hilda Doolittle before she became H. D., and had a lifelong, if sometimes turbulent, correspondence with Ezra Pound. His work was well known to the expatriates who fre- quented Sylvia Beach’s bookshop in Paris in the 1920s well before his own visit there in 1924. He was friends with painters Charles Demuth, Marsden Hartley, Charles Sheeler, and Ben Shahn, and purchased Demuth and Hartley’s work when their buyers were few. He knew and corresponded with novelists Ford Madox Ford and Nathanael West, with critic Kenneth Burke, and poet Louis Zukofsky. He won the first National Book Award and a posthumous Pulitzer Prize; was a member of the Academy of Arts and Letters; was a mainstay for years, along with Pound, of James Laughlin’s New Directions; and in his last decade was the subject of pilgrimages to his suburban New Jersey house by such figures as Jack Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg, and Gregory Corso. -

A Magazine of Verse Edited by Harriet Monroe July 1918

Vol. XII No. IV A Magazine of Verse Edited by Harriet Monroe July 1918 Prairie by Carl Sandburg Kaleidoscope by Marsden Hartley D. H. Lawrence, Eloise Robinson, William Carlos Williams Poems by Children 543 Cass Street. Chicago $2.00 per Year Single Numbers 20c There ia no magazine published in this country which has brought me such delight as your POETRY. I loved it from the beginning of its existence, and 1 hope that it may live forever. A Subscriber POETRY for JULY, 1918 PAGE Prairie Carl Sandburg 175 Island Song Robert Paini Scripps 185 Moonrise—People D.H. Lawrence 186 Sacrament Pauline D. Partridge 187 The Trees Eloise Robinson 188 Crépuscule Maxwell Struthers Burt 189 There Was a Rose—An Old Man's Weariness Arthur L. Phelps 190 The Screech Owl J.E.Scruggs 191 Le Médecin Malgré Lui William Carlos Williams 192 Plums P. T. R. 193 • To a Phrase ' Hazel Hall 194 Kaleidoscope Marsden Hartley 195 In the Frail Wood—Spinsters—Her Daughter—After Battle I-III Poems by Children : Fairy Footsteps I-VIII Hilda Conkling 202 Sparkles I-III Elmond Franklin McNaught 205 In the Morning Juliana Allison Bond 205 Ripples I-IV Evans Krehbiel 206 Mr. Jepson's Slam H.M. 208 The New Postal Rate H. M. 212 Reviews: As Others See Us Alfred Kreymborg 214 Mr. O'Neil's Carvings Emanuel Carnevali 225 Correspondence: Of Puritans, Philistines and Pessimists .... A. CH. 228 An Anthology of 1842 Willard Wattles 230 Notes and Books Received 231 Manuscripts must be accompanied by a stamped and self-addressed envelope. -

Harriet Monroe's Abraham Lincoln

Harriet Monroe’s Abraham Lincoln MARK B. POHLAD It takes a great deal of history to produce a little literature. —Henry James In 1919, when Harriet Monroe reviewed a new stage hit Abraham Lincoln, by British playwright John Drinkwater, it was already a Broad- way smash and would run continuously for five years in nearly every major American city.1 Although audiences were clearly thrilled, Mon- roe resented the play and found it completely unconvincing: Mr. Drinkwater picks [Lincoln] up out of his own place, and sets him down in a manufactured milieu, where the people do not think his thoughts nor speak his tongue, and even the chairs don’t look natural.2 Her last observation is so withering it deserves a permanent place in theater history.3 What could have so upset Monroe about a portrayal of Lincoln? And how did she come to be so invested in the representation of Illinois’ most famous son? What was her relationship to Lincoln’s memory, and how did it influence her editorial entrepreneurship? Monroe was instrumental in shaping the modern literary treatment of Abraham Lincoln (fig. 1). She revered his memory and advanced the careers of authors who engaged Lincoln as a subject in their work. 1. Roy P. Basler, “Lincoln and American Writers,” Papers of the Abraham Lincoln Asso- ciation 7 (1985), 9. 2. Harriet Monroe, “Review: A Lincoln Primer,” Poetry: A Magazine of Verse 15 (December 1919), 161. 3. Monroe apparently did not read Drinkwater’s introduction to the published ver- sion of the play in which the author graciously confesses his limitations: “I am an Englishman, and not a citizen of the great country that gave Lincoln birth. -

William Carlos Williams

William Carlos Williams: An Inventory of His Collection at the Harry Ransom Center Descriptive Summary Creator: Williams, William Carlos, 1883-1963 Title: William Carlos Williams Collection Dates: 1928-1971 Extent: 4 document boxes (1.68 linear feet) Abstract: The William Carlos Williams Collection consists of manuscripts and correspondence by Williams; manuscripts, correspondence, and research notes about Williams by scholar John C. Thirlwall; and correspondence about Williams by other authors. Major works represented in draft form include Williams' Life Along the Passaic River (1938) and Thirlwall's edition of the Selected Letters of William Carlos Williams (1957). Correspondents represented include David McDowell, Marcia Nardi, Bonnie Golightly, and Srinivas Rayaprol. The collection is arranged in four series: I. Works, 1936-1960, undated; II. Correspondence, 1928-1961, undated; III. John C. Thirlwall Materials, 1951-1971, undated; and IV. Correspondence by Other Authors, 1946-1968, undated. Language: English Access: Open for research Administrative Information Acquisition: Purchases and gifts, 1961-1995 (R 942, R1027, R2897, R3377, R4103, R4591, R5374, R7152, R11685, G9033, G10239, R13411, R13444) Processed by: Elspeth Healey, 2010 Repository: The University of Texas at Austin, Harry Ransom Center Williams, William Carlos, 1883-1963 Biographical Sketch William Carlos Williams was born on September 17, 1883, in Rutherford, New Jersey, the same town where he would die nearly eighty years later. His father, William George Williams, was a British-born merchant who, since childhood, had lived in the Caribbean. His mother, Rachel Elena Hoheb, was from Puerto Rico and had studied painting in Paris. The couple moved to Rutherford shortly after their marriage in Brooklyn, New York. -

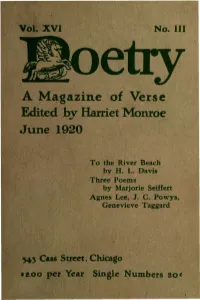

A Magazine of Verse Edited by Harriet Monroe June 1920

Vol. XVI No. III A Magazine of Verse Edited by Harriet Monroe June 1920 To the River Beach by H. L. Davis Three Poems by Marjorie Seiffert Agnes Lee, J. C. Powys, Genevieve Taggard 543 Cass Street. Chicago $2.00 per Year Single Numbers 20c Your magazine is admirably American in spirit—modern cosmopolitan America, not the insular America of bygone days. Evelyn Scott Vol. XVI No. III POETRY for JUNE, 1920 PAGE To the River Beach H. L. Davis 117 In this Wet Orchard—Stalks of Wild Hay—Baking Bread —The Rain-crow—The Threshing-floor—From a Vine yard—The Market-gardens—October: "The Old Eyes"— To the River Beach Sleep Poems Agnes Lee 128 Old Lizette on Sleep—The Ancient Singer—Mrs. Malooly —The Ilex Tree Three Poems Marjorie Allen Sieffert 131 Cythaera and the Leaves—Cythaera and the Song— C3'thaera and the Worm Transition Eleanor Hammond 133 Surrender Irwin Granich 134 Out of the Dark A. N. 135 Songs I-IV Glenn Ward Dresbach 136 The Riddle John Cowper Powys 138 The Shepherd Hymn Gladys Hensel 139 Cold Hills Janet Loxley Lewis 140 Austerity—The End of the Age—Geology—Fossil From the Frail Sea Genevieve Taggard 142 Men or Women? H. M. 146 Discovered in Paris H. M. Reviews: Starved Rock M. A. Seiffert 151 Perilous Leaping Marion Strobel 157 Out of the Den Babette Deutsch 159 Black and Crimson Marion Strobel 162 Standards of Literature .... Richard Aldington 164 Our Contemporaries: New English Magazines H. M. 168 Correspondence: ManuscriptRiddles s anmusdt bRunee accompanies . d.