Little Shuswap Indian Band

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SEVEN HABITS of HIGHLY EFFECTIVE FIRST NATIONS by TOM FLANAGAN and LEE HARDING FRONTIER CENTRE for PUBLIC POLICY Ideas That Change Your World

PFRONTIEROLICY CENTRE SFORERIES PUBLIC POLICY No. 189 • NOVEMBER 2016 SEVEN HABITS OF HIGHLY EFFECTIVE FIRST NATIONS BY TOM FLANAGAN AND LEE HARDING FRONTIER CENTRE FOR PUBLIC POLICY Ideas that change your world / www.fcpp.org This paper is co-published in association with The Atlantic Institute for Market Studies (AIMS) 1 FRONTIER CENTRE FOR PUBLIC POLICY TOM FLANAGAN, Chair, Aboriginal Futures Tom Flanagan is the Chair of the Aboriginal Futures program. He is Professor Emeritus of Political Science at University of Calgary, where he taught for more than 45 years, serving as Department Head, Advisor to the President and a Distinguished Fellow at the School of Public Policy. Dr. Flanagan has been Chief of Staff to Prime Minister Stephen Harper and a strategy and campaign advisor to numerous federal and provincial political campaigns. He is a Fellow of the Royal Society of Canada. Dr. Flanagan is a monthly columnist for the Globe & Mail and frequent contributor to national and international press such as MacLeans and Time magazines. He is the author of several award-winning books on aboriginal topics, including Metis Lands in Manitoba, First Nations? Second Thoughts and Beyond the Indian Act. LEE HARDING, Intern Lee Harding is a Master’s Candidate at the School of Public Policy at the University of Calgary. He also has a Bachelor of Arts in Journalism from the University of Regina and a Bachelor of Arts in Theology from Briercrest College and Seminary. After working as a television reporter for CBC, CTV, and Global in Regina, Saskatchewan, he joined the Canadian Taxpayers Federation in 2007 to become its Saskatchewan Director. -

Secwepemc Injury Surveillance & Prevention Program

Secwepemc Injury Surveillance & Prevention Program Participating Communities Year Joined: Esketemc February 2005 Inside this issue Three Corners Health Services Society (TCHSS) March 2005 Sxqeltqin Health ------ pg. 2 (Soda Creek Indian Band, Williams Lake Indian Band, Stswecem'c Xgat'tem First Nation) (Adams Lake) Qwemtsin Health Society May 2005 Little Shuswap --------- pg. 3 (Tk’emlups, Skeetchestn, Whispering Pines) Esketemc---------------- pg. 3 Adams Lake September 2005 TCHSS -------------------- pg. 4-5 Canim Lake Band (Tsq’escen) February 2006 Concussion Info ------ pg. 6 Little Shuswap Lake May 2006 Qwemtsin Health ----- pg. 7 Simpcw January 2013 Splatsin ------------------ pg. 7 Splatsin January 2013 Neskonlith September 2016 Contact Information pg. 8 Bonaparte September 2016 The Secwepemc Nation Injury Surveillance and Prevention Program helps communities collect information on injuries that happen in their respected communities. Each community will collect specific information on injuries by distributing a form to help collect the necessary information, the form which asks the 5 W’s: Who (age and gender), What (what happened), Where (injury occurred), When (date & time of day), and Why. The information collected will then be entered into an electronic database to generate reports and find out what injuries are taking place throughout a period of time. Communities can then use this information to start prevention programs in their communities. In order for us to get the most accurate information possible, we would like to encourage that ALL injuries be reported, regard- less of severity. Boozhoo-Greetings. My name is Jennifer and I was recently gifted my Anishinaabe name: Keesis Sagay Egette Ekwé, which translates to First Shining Rays of Sunlight Woman in honor of completing my doctorate from UBC. -

First Nation Address List

(Version: November 16 05) KAMLOOPS FOREST DISTRICT - FIRST NATION ADDRESS LIST I. SHUSWAP NATION TRIBAL COUNCIL (SNTC): Shuswap Nation Tribal Council Neskonlith Indian Band (Sk’emtsin) Chair Chief Nathan Matthew Chief Art Anthony and Council Suite #304-355 Yellowhead Highway P.O. Box 608 Kamloops, B.C. #33 Chief Neskonlith Rd V2H 1H1 Chase, B.C. Ph (250) 828- 9789 V0E 1M0 Fax (250) 374-6331 Ph (250) 679-3295 Fax (250) 679-5306 AOA Contact: Chief Art Anthony, Sharon Jules Adams Lake Indian Band (Sexqeltqi’n) Simpcw First Nation Chief Ron Jules and Council (North Thompson Indian Band) P.O. Box 588 Chief Nathan Matthew and Council Chase, B.C. P.O. Box 220 V0E 1M0 500 Dunn Lake Road Ph (250) 679-8841 Barriere, B.C. Fax (250) 679-8813 V0E 1E0 Cc Dave Nordquist, Natural Resources Manager Ph (250) 672-9995 AOA Contact: Dave Nordquist Fax (250) 672-5858 AOA Contact: Nancy Jules; Joe Jules Bonaparte Indian Band (St’uxwtews) Skeetchestn Indian Band Chief Mike Retasket and Council Chief Ed Jules and Council P.O. Box 669 330 Main Drive Cache Creek, B.C. Box 178 V0K 1H0 Savona, B.C. Ph:(250) 457-9624 V0E 2J0 Fax (250) 457-9550. Has FRA Ph (250) 373-2493 AOA Contact: Chief Mike Retasket; Bert Fax (250) 373-2494 Williams AOA Contact: Mike Anderson; Lea McNabb High Bar Indian Band Spallumcheen Band (Splats’in) Chief Lenora Fletcher and Council Chief Gloria Morgan and Council P.O. Box 458 5775 Old Vernon Road Clinton, BC Box 460) V0K 1K0 Enderby, B.C. -

Adams River As a Heritage River.Pdf

Draft Nomination Document for the Adams River As a Canadian Heritage River Prepared for B.C. Ministry of Environment By Cal-Eco Consultants Ltd. March 31, 2006 Version 1.2 1 The Canadian Heritage Rivers System The Canadian Heritage Rivers System (CHRS) is Canada's national river conservation system, aimed at promoting, protecting and enhancing Canada's river heritage. The system has been established by the Federal, Provincial and Territorial governments for the purpose of recognizing outstanding rivers of Canada, and ensuring future management which will protect these rivers and enhance their significant heritage values for the long term benefit and enjoyment of Canadians. The CHRS operates under a charter that describes rivers as "0 priceless olld irreplaceoblepart of our 1I0lio1101 heriloge olld idmti!j'. In British Columbia, the Fraser, Kickinghorse and Cowichan Rivers have been designated as Heritage Rivers under the CHRS. To qualify for inclusion in the CHRS, a river (or section of river) must be of outstanding significance in one or more areas: natural heritage, human heritage, or recreational values. The process of nominating a Canadian Heritage River requires an assessment of a river's natural, cultural and recreational values against criteria set out by the CHRS. While the CHRS is administered by the Canadian Heritage Rivers Board, a fundamental ptinciple of the system is that it depends on voluntary participation, parmership, cooperation and community involvement. The CHRS has no legislative authority, and as such, Local, Provincial -

North Thompson Official Community Plan

Schedule “A” to Bylaw 2700 North Thompson Official Community Plan Foreword and Acknowledgements The North Thompson Official Community Plan is the outcome of over two years of research, public participation and planning. The Regional District is grateful to all those residents and groups who provided interest, passion, and support from all corners of the Plan area culminating in the Plan development. In particular, we wish to recognize the following people for the exceptional amount of time and energy they dedicated to the planning process. OCP Advisory Committee Director Carol Schaffer, Electoral Area “A” Director Stephen Quinn, Electoral Area “B” Director Bill Kershaw, Electoral Area “O” Tom Eustache – Simpcw First Nation Rick Dee Harley Wright Willow Macdonald (past member) Meetings, Conversations and Information Providers Anna Kay Eldridge – Simpcw First Nation Ashley Dyck – Planning Services Celia Nord – Little Shuswap Indian Band Chris Ortner Dan Winiski Doris Laner – North Thompson Arts Council James Demens and Brandon Gustafsen – Ministry of Transportation and Infrastructure Jenny Green and Clare Audet – Interior Health Authority Kelly Funk – Kelly Funk Photography Laura Ryser – Research Manager, Rural and Small Town Studies Program, UNBC Leanne Nystoruk Mike Scarff, TNRD GIS Services PIBC and the Planners from the local Interior Chapter Sarah Cooke and Mike Cloet – Ministry of Mines, Energy and Petroleum Resources Staff and students at Clearwater and Barriere Secondary Schools Staff from the Agricultural Land Commission Staff -

The Struggle for Indigenous Representation in Canadian National Parks: the Case of the Haida Totem Poles in Jasper

Journal of Indigenous Research Full Circle: Returning Native Research to the People Volume 8 Issue 2020 March 2020 Article 1 March 2020 The Struggle for Indigenous Representation in Canadian National Parks: The Case of the Haida Totem Poles in Jasper Jason W. Johnston Thompson Rivers University, [email protected] Courtney Mason Thompson Rivers University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/kicjir Recommended Citation Johnston, Jason W. and Mason, Courtney (2020) "The Struggle for Indigenous Representation in Canadian National Parks: The Case of the Haida Totem Poles in Jasper," Journal of Indigenous Research: Vol. 8 : Iss. 2020 , Article 1. DOI: https://doi.org/10.26077/7t6x-ds86 Available at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/kicjir/vol8/iss2020/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Indigenous Research by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Struggle for Indigenous Representation in Canadian National Parks: The Case of the Haida Totem Poles in Jasper Cover Page Footnote To the Indigenous participants and the participants from Jasper National Park, thank you. Without your knowledge, passion and time, this project would not have been possible. While this is only the beginning, your contributions to this work will lead to a deeper understanding and appreciation for the complexities of the issues surrounding Indigenous representation in national parks. This article is available in Journal of Indigenous Research: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/kicjir/vol8/iss2020/1 Johnston and Mason: The Struggle for Indigenous Representation in Canadian National Parks The Struggle for Indigenous Representation in Canadian National Parks: The Case of the Haida Totem Poles in Jasper National parks hold an important place in the identities of many North Americans. -

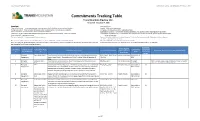

Commitments Tracking Table Trans Mountain Pipeline ULC Version 20 - December 7, 2018

Trans Mountain Expansion Project Commitment Tracking Table (Condition 6), December 7, 2018 Commitments Tracking Table Trans Mountain Pipeline ULC Version 20 - December 7, 2018 Project Stage Commitment Status "Prior to Construction" - To be completed prior to construction of specific facility or relevant section of pipeline "Scoping" - Work has not commenced "During Construction" - To be completed during construction of specific facility or relevant section of pipeline "In Progress - Work has commenced or is partially complete "Prior to Operations" - To be completed prior to commencing operations "Superseded by Condition" - Commitment has been superseded by NEB, BC EAO condition, legal/regulatory requirement "Operations" - To be completed after operations have commenced, including post-construction monitoring conditions "Superseded by Management Plan" - Addressed by Trans Mountain Policy or plans, procedures, documents developed for Project "Project Lifecycle" - Ongoing commitment design and execution "No Longer Applicable" - Change in project design or execution "Superseded by TMEP Notification Task Force Program" - Addressed by the project specific Notification Task Force Program "Complete" - Commitment has been met Note: Red text indicates a change in Commitment Status or a new Commitment, from the previously filed version. "No Longer Applicable" - Change in project design or execution Note: As of August 31, 2018, Kinder Morgan ceased to be an owner of Trans Mountain. References to Kinder Morgan Canada or KMC in the table below have -

Language List 2019

First Nations Languages in British Columbia – Revised June 2019 Family1 Language Name2 Other Names3 Dialects4 #5 Communities Where Spoken6 Anishnaabemowin Saulteau 7 1 Saulteau First Nations ALGONQUIAN 1. Anishinaabemowin Ojibway ~ Ojibwe Saulteau Plains Ojibway Blueberry River First Nations Fort Nelson First Nation 2. Nēhiyawēwin ᓀᐦᐃᔭᐍᐏᐣ Saulteau First Nations ALGONQUIAN Cree Nēhiyawēwin (Plains Cree) 1 West Moberly First Nations Plains Cree Many urban areas, especially Vancouver Cheslatta Carrier Nation Nak’albun-Dzinghubun/ Lheidli-T’enneh First Nation Stuart-Trembleur Lake Lhoosk’uz Dene Nation Lhtako Dene Nation (Tl’azt’en, Yekooche, Nadleh Whut’en First Nation Nak’azdli) Nak’azdli Whut’en ATHABASKAN- ᑕᗸᒡ NaZko First Nation Saik’uz First Nation Carrier 12 EYAK-TLINGIT or 3. Dakelh Fraser-Nechakoh Stellat’en First Nation 8 Taculli ~ Takulie NA-DENE (Cheslatta, Sdelakoh, Nadleh, Takla Lake First Nation Saik’uZ, Lheidli) Tl’azt’en Nation Ts’il KaZ Koh First Nation Ulkatcho First Nation Blackwater (Lhk’acho, Yekooche First Nation Lhoosk’uz, Ndazko, Lhtakoh) Urban areas, especially Prince George and Quesnel 1 Please see the appendix for definitions of family, language and dialect. 2 The “Language Names” are those used on First Peoples' Language Map of British Columbia (http://fp-maps.ca) and were compiled in consultation with First Nations communities. 3 The “Other Names” are names by which the language is known, today or in the past. Some of these names may no longer be in use and may not be considered acceptable by communities but it is useful to include them in order to assist with the location of language resources which may have used these alternate names. -

PROVINCI L Li L MUSEUM

PROVINCE OF BRITISH COLUMBIA REPORT OF THE PROVINCI_l_Li_L MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY • FOR THE YEAR 1930 PRINTED BY AUTHORITY OF THE LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY. VICTORIA, B.C. : Printed by CHARLES F. BANFIELD, Printer to tbe King's Most Excellent Majesty. 1931. \ . To His Honour JAMES ALEXANDER MACDONALD, Administrator of the Province of British Columbia. MAY IT PLEASE YOUR HONOUR: The undersigned respectfully submits herewith the Annual Report of the Provincial Museum of Natural History for the year 1930. SAMUEL LYNESS HOWE, Pt·ovincial Secretary. Pt·ovincial Secretary's Office, Victoria, B.O., March 26th, 1931. PROVINCIAl. MUSEUM OF NATURAl. HISTORY, VICTORIA, B.C., March 26th, 1931. The Ho1Wm·able S. L. Ho11ie, ProvinciaZ Secreta11}, Victo1·ia, B.a. Sm,-I have the honour, as Director of the Provincial Museum of Natural History, to lay before you the Report for the year ended December 31st, 1930, covering the activities of the Museum. I have the honour to be, Sir, Your obedient servant, FRANCIS KERMODE, Director. TABLE OF CONTENTS . PAGE. Staff of the Museum ............................. ------------ --- ------------------------- ----------------------------------------------------- -------------- 6 Object.. .......... ------------------------------------------------ ----------------------------------------- -- ---------- -- ------------------------ ----- ------------------- 7 Admission .... ------------------------------------------------------ ------------------ -------------------------------------------------------------------------------- -

Indian Band Revenue Moneys Order Décret Sur Les Revenus Des Bandes D’Indiens

CANADA CONSOLIDATION CODIFICATION Indian Band Revenue Moneys Décret sur les revenus des Order bandes d’Indiens SOR/90-297 DORS/90-297 Current to October 11, 2016 À jour au 11 octobre 2016 Last amended on December 14, 2012 Dernière modification le 14 décembre 2012 Published by the Minister of Justice at the following address: Publié par le ministre de la Justice à l’adresse suivante : http://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca http://lois-laws.justice.gc.ca OFFICIAL STATUS CARACTÈRE OFFICIEL OF CONSOLIDATIONS DES CODIFICATIONS Subsections 31(1) and (3) of the Legislation Revision and Les paragraphes 31(1) et (3) de la Loi sur la révision et la Consolidation Act, in force on June 1, 2009, provide as codification des textes législatifs, en vigueur le 1er juin follows: 2009, prévoient ce qui suit : Published consolidation is evidence Codifications comme élément de preuve 31 (1) Every copy of a consolidated statute or consolidated 31 (1) Tout exemplaire d'une loi codifiée ou d'un règlement regulation published by the Minister under this Act in either codifié, publié par le ministre en vertu de la présente loi sur print or electronic form is evidence of that statute or regula- support papier ou sur support électronique, fait foi de cette tion and of its contents and every copy purporting to be pub- loi ou de ce règlement et de son contenu. Tout exemplaire lished by the Minister is deemed to be so published, unless donné comme publié par le ministre est réputé avoir été ainsi the contrary is shown. publié, sauf preuve contraire. -

The Wealth of First Nations

The Wealth of First Nations Tom Flanagan Fraser Institute 2019 Copyright ©2019 by the Fraser Institute. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief passages quoted in critical articles and reviews. The author of this book has worked independently and opinions expressed by him are, there- fore, his own and and do not necessarily reflect those of the Institute, its Board of Directors, its donors and supporters, or its staff. This publication in no way implies that the Fraser Institute, its directors, or staff are in favour of, or oppose the passage of, any bill; or that they support or oppose any particular political party or candidate. Printed and bound in Canada National Library of Canada Cataloguing in Publication Data The Wealth of First Nations / by Tom Flanagan Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 978-0-88975-533-8. Fraser Institute ◆ fraserinstitute.org Contents Preface / v introduction —Making and Taking / 3 Part ONE—making chapter one —The Community Well-Being Index / 9 chapter two —Governance / 19 chapter three —Property / 29 chapter four —Economics / 37 chapter five —Wrapping It Up / 45 chapter six —A Case Study—The Fort McKay First Nation / 57 Part two—taking chapter seven —Government Spending / 75 chapter eight —Specific Claims—Money / 93 chapter nine —Treaty Land Entitlement / 107 chapter ten —The Duty to Consult / 117 chapter eleven —Resource Revenue Sharing / 131 conclusion —Transfers and Off Ramps / 139 References / 143 about the author / 161 acknowledgments / 162 Publishing information / 163 Purpose, funding, & independence / 164 About the Fraser Institute / 165 Peer review / 166 Editorial Advisory Board / 167 fraserinstitute.org ◆ Fraser Institute Preface The Liberal government of Justin Trudeau elected in 2015 is attempting massive policy innovations in Indigenous affairs. -

Joint Federal/Provincial Consultation and Accommodation Report for the Trans Mountain Expension Project

Joint Federal/Provincial Consultation and Accommodation Report for the Trans Mountain Expansion Project November 2016 Joint Federal/Provincial Consultation and Accommodation Report for the TRANS MOUNTAIN EXPANSION PROJECT TABLE OF CONTENTS Acronyms, Abbreviations and Definitions Used in This Report ...................... xi 1. INTRODUCTION .......................................................................... 1 1.1 Purpose of the Report ..............................................................................1 1.2 Project Description .................................................................................2 1.3 Regulatory Review Including the Environmental Assessment Process .....................7 1.3.1 NEB REGULATORY REVIEW AND ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT PROCESS ....................7 1.3.2 BRITISH COLUMBIA’S ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT PROCESS ...............................8 1.4 NEB Recommendation Report.....................................................................9 2. APPROACH TO CONSULTING ABORIGINAL GROUPS ........................... 12 2.1 Identification of Aboriginal Groups ............................................................. 12 2.2 Information Sources .............................................................................. 19 2.3 Consultation With Aboriginal Groups ........................................................... 20 2.3.1 PRINCIPLES INVOLVED IN ESTABLISHING THE DEPTH OF DUTY TO CONSULT AND IDENTIFYING THE EXTENT OF ACCOMMODATION ........................................ 24 2.3.2 PRELIMINARY