Exploring the Musical Experience, Its Attachments and Its Technologies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MEDIA KIT M K E D I a Audio SOUL PROJECT

AL MA KEEPING IT UNREAL SINCE 1991 I Z IC I F F O MEDIA KIT ASP AUDIO I T SOUL PROJECT M K E D I A AUDIO SOUL PROJECT A prolific producer, Mazi Namvar has written Recordings, Cates & dPL’s “Through The or remixed over 200 records in 15 years Weekend” on OM Records, Alexander time. He works under several pseudonyms Maier’s “Sahara Rain” on Mood Music, Nick the most popular of which is Audio Soul and Danny Chatelain’s “Sube Conmigo” Project. Current original ASP releases have on NRK, Chaim’s “C Factor” on Missive appeared on Dessous, Systematic, Circle Recordings and Matthias Vogt’s “Roofs” on Music, SAW, Mood Music and Ovum. Fresh Meat. His latest production “Traditionalist” for Systematic recordings was featured on that A DJ for 18 years, Mazi has visited clubs label’s 5 vinyl box set entitled “5YSYST” like Fabric in London, Crystal in Istanbul, Q and reached the top 10 Deep House chart in Zürich, Avalon in Los Angeles, Masai in on Beatport.com. His music has recently Varna, Level in Bahrain, Red Light in Paris appeared on compilations such as Loco and Simoon in Tokyo. He still finds time to Dice “The Lab01” on NRK Music, Darren play in Chicago, DJ’ing or performing live Emerson’s “Bogota GU36” on Global at local venues like Spy Bar, Moonshine, Underground, Ralph Lawson’s “Fabric 33” Zentra, Vision and Smart Bar. mix, Sander Kleinenberg’s edition of the famous “This Is” Renaissance series and on As an A & R executive, Mazi presides over the 9th volume of the “KM5 Ibiza” series on his label Fresh Meat Records which he co- Belgium’s impeccable NEWS label. -

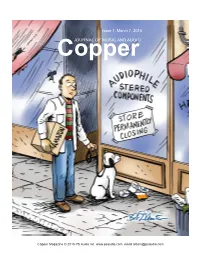

Psaudio Copper

Issue 1 MARCH 7TH, 2016 The birth of a child is always a cause for celebration. For the new parent, it's also a time of uncertainty and anxiety: Am I doing this right? Is THAT normal?? Creating Copper has been pretty much the same for us. There is exhilaration, the excitement of starting something completely new, of charting the course as we go. And of course, there is the desire to do everything perfectly. The first issue of Copper, now before you, requires a little by way of introduction. Copper is dedicated to furthering the art of home audio reproduction, and growing the community that supports it. Whether you call it Hi-Fi, hi-res, or High-End doesn't matter; such labels tend to separate and isolate people, which is exactly what we don't want to do. We'll do our best not to be audio snobs. Any system, technology, or category of product that faithfully reproduces music, honoring its source and intent, qualifies as fair game to us. Vinyl, digital, portable, expensive, inexpensive, new or old: if it makes music, it's of interest to our readers. Copper is not a traditional audio magazine. It is published by a well-established audio manufacturer, and we hope you do buy our products... but that's not the point of this magazine. Copper won't sell or promote products, services, or advertising. Instead, Copper aims to inform, entertain, inspire, motivate and build community. We believe that a diverse, strong, well informed community of like-minded people, sharing ideas, news, and knowledge benefits all. -

Hannah Pezzack

Hannah Pezzack Tel. 07500117971 Email: [email protected] Address: 99 Billesley Lane, Moseley, B13 9RB DoB: 21/06/1995 Highly motivated, organized and creative university graduate with a flair for writing, excellent attention to detail and an aptitude for producing engaging content. My experience and skills have tailored me into the ideal candidate for jobs in creative marketing, fundraising, online media and communications. Flux Magazine – Journalist As a feature writer for this online magazine, I create engaging and up to date articles about the world of music. Flux is a nationally and internationally recognised brand, with over 16, 000 “likes” on Facebook, and was nominated by DJ mag as the UK’s best night club. http://www.fluxmusic.net/info/ The Gryphon Newspaper – Music Journalist Interviewed famous artists and DJ’s including Dubstep producer Mala and Back To Basic’s Dave Beer. Responded positively to editor feedback and was always seeking to improve my work. Nominated Article of the Year 2016 & 2017, thus demonstrating the strength and originality of my writing. Portfolio of writing for The Gryphon: http://www.thegryphon.co.uk/tag/hannah-pezzack/ Positive Causes – Fundraiser (July - September 2016) On the busy high street in Cardiff city centre I encouraged people to buy the charity’s magazine, and spread awareness about the organisation and its important work. Built skills as a clear and polite communicator. Prepared, informed and sensitive in order to answer any questions. Consistently able to go above the daily sale target of the magazine. Tibet World – Volunteer (June – July 2016) Conducted English lessons: instructing a class of over 30 individuals of varying levels of English. -

Kings of Conveniencedeclaration of Dependence Full Album Zip

Kings Of Convenience-Declaration Of Dependence Full Album Zip 1 / 4 Kings Of Convenience-Declaration Of Dependence Full Album Zip 2 / 4 3 / 4 Tracklist: 1. Winning A Battle, Losing The War, 2. ... Loading... Play album. 0:00. Track playing: ... Declaration Of Dependence · Kings Of Convenience 13 tracks .... ... Dependence at Discogs. Complete your Kings Of Convenience collection. ... Declaration Of Dependence album cover. More Images · Edit Master ... Tracklist .... Kings Of Convenience - Riot On An Empty Street - Amazon.com Music. ... Declaration Of Dependence by Kings of Convenience Audio CD $11.66 ... Because these Kings of melodic music have struck again with their second full length disc.. Kings of Convenience son un dúo de Indie pop - Folk Pop formado por Erlend Øye y Eirik Glambek Bøe y ... (2009) Declaration of Dependence.. Declaration Of Dependence Kings Of Convenience Rar ... Kings Of Convenience-Declaration Of Dependence Full Album Zip >> DOWNLOAD .... Release Date: 2004 | Tracklist. Kings of Convenience is the mellow indie pop duo of Eirik Glambek Bøe and Erlend Øye. Riot on an Empty Street is their third major label album, and ended a three year layoff ... i need to listen to declaration of dependence still. i think this is the only album with a review.. Declaration of Dependence is the third album from Norwegian duo Kings of Convenience and it is also their first album in five years. It was planned for release in .... Declaration Of Dependence Kings Of Convenience Rar ... -i-could-be-the-only-one-zip https://easchelmahar.typeform.com/to/SAAN4a .... Kings Of Convenience, Declaration Of Dependence Full Album Zip, ispring pro full x64 indowebster 63e72d5f49 3. -

Thugs Sent Round to Threaten Tenants LANDLORD DRAFTS IN

Incorporating juice magazine Guardian/ NUS Student Newspaper of the Year Thugs sent round to threaten tenants LANDLORD DRAFTS IN HEAVBy GARETH EVANS Y MOB THREE finalists fled their house days before their exams, claiming a gang threatened them with violence if they refused to pay outstanding rent. Merewyn Fenton, Chris Greenfield and Scott Dinnis left EXCLUSIVE! their house within a day of the alleged threats and stayed at home. First British They claim they were threatened by a gang of men who barged into their house review of and warned they could expect violence if they did not pay up. It is the latest chapter in a year of conflict with their estate agents, which looks set to end up in court. Demands The agencx sent letters demanding more thai) two thousand pounds which also co\ered repair \\ork. The students took legal ad\ ice. convinced thcx \\ ere not liable tor these expenses and claim the agents reacted b\ sending oxer the thugs. "Scott and 1 xxerc out so Chris xxas alone in the house." said Merexxxn. "these txxo blokes came around asking lo look round the house, \\heii he opened the door thex pushed him inside and told him it xxc didn't pax up. thex xxould come back and beat us all up. Chris is usuallx an casx -going bloke, but he xxas really shaken up." The trouble began xxhen one housemate left in September lor a xxork placement leax ing the remaining BRAVE BATTLER: LMU graduate Vicki Hunter is suing three to find another person to till their house Birmingham Health Authority for damages, claiming a A I'orlugiicsc waiter moxed in but left txxo months misdiagnosis resulted in the loss of her leg which was later \\ithout pax ing an\ deposit, rent or hills. -

Declaration of Dependence Kings of Convenience Rar

Declaration Of Dependence Kings Of Convenience Rar 1 / 4 Declaration Of Dependence Kings Of Convenience Rar 2 / 4 3 / 4 Declaration Of Dependence Kings Of Convenience Rar >>> http://bltlly.com/14kkih.. Shop for Vinyl, CDs and more from Kings Of Convenience at the Discogs Marketplace. ... Kings of Convenience are an indie folk-pop duo from Bergen, Norway. ... ASW 06840, Kings Of Convenience - Declaration Of Dependence album art .... Plik Kings Of Convenience 2009 Declaration Of Dependence.rar na koncie użytkownika SumaWszystkichLudzi • folder 2009-Declaration Of Dependence • Data .... Download: «Declaration of Dependence» – Kings of Convenience. Descargas, Radio. Muchos de ustedes han compartido a través de sus comentarios la .... Riot On An Empty Street Kings Of Convenience Rar ... Cayman Islands Riot On An Empty Street 3:02 1.29 4 Freedom And Its Owner Declaration Of Dependence .... 38bdf500dc Kings Of Convenience-Declaration Of Dependence Full Album Zip >> DOWNLOAD (Mirror #1) e31cf57bcd Cerita Hantu Malaysia .... “Failure” (aransemen oleh Kings of Convenience) – 4:56 11. “Leaning Against the ... Declaration of Dependence (2009). 1. “24-25” 3:38 2.. Kings Of Convenience - Me in You (Letras y canción para escuchar) - Crossroads and given the option ... Declaration Of Dependence Kings Of Convenience.. 2009 release, the third album from the Norwegian Pop/Folk duo (Erik Boe and Erlend Oye). Declaration of Dependence is the story of two people living two very .... Declaration of Dependence is the third album from Norwegian duo Kings of Convenience, their first album in five years. It was released on October 5, 2009.. Kings of Convenience son un dúo de Indie pop - Folk Pop formado por Erlend Øye y Eirik Glambek Bøe y .. -

DIAMONDS & MUSIC I

$6.99 (U.S.), $3.39 (CAN.), £5.50 (U.K.), 8.95 (EUROPE), Y2,500 (JAPAN) aw N W Z : -DIGIT 908 Illllllllllll llllllllllllllll lllllllllllllllllll I B1240804 APROE A04 E0101 MONTY GREENLY 3740 ELM AVE N A LONG BEACH CA 90807 -3402 THE INTERNAT ON4L AUTHORITY ON ML SIC, VIDEO AND DIGITAL ENTERTAINMENT AUGUST 21, 20C4 LUXU Q\Y" E É DIAMONDS & MUSIC i SPE(IAL REPORT INSIDE i www.americanradiohistory.com HOW ABOUT YOU BLINDING THE PAPARAZZI FOR A CHANGE A DIAMOND IS FOREVER ¡ THE FOREVERMPRK IS USED UNDER LICENSE. WWW.P DIA MIONDIS FOREVER.COM www.americanradiohistory.com $6.99 (U.S.), $8.99 (CAN.), £5.50 (U.K.), 8.95 (EUROPE), Y2,500 (JAPAN) aw a `) zW Iong Specia eport Begins On Page 19 www.billboard.com THE INTERNATIONAL AUTHORITY ON MUSIC, VIDEO AND DIGITAL ENTERTAINMENT 110TH YEARra AUGUST 21, 2004 HOT SPOTS Battling To Save Archives At Risk BY BILL HOLLAND When it comes to recorded music archives, there ain't nothing like the real thing. As technology evolves, it is essential, archivists say, that re- issues on new audio platforms be based on original masters. Unfortunately, in an unexpected by- product of digital - era recording, many original masters are in danger of dete- riorating or becoming obsolete. 13 A Bright Remedy That's because the material was This is a first in a Meredith Brooks' 2002 single recorded on early digital equipment two -part series on the challenges `Shine' re- emerges as the that is no longer manufactured. In U.S. record new song `The Dr. -

Music We for Everyone in the Business of Music Mcgee and Branson

music we For Everyone in the Business of Music JULY 261997 £3.35 Mercury faces THIS WEEK McGee and Branson: name change 4 Strong importspoundsees rise 5Music Mercury Pnze: 'We'llfiglit for music' by Martin Talbot He says the création of the commit- A spokesman for Branson says he STelstar Prodigy's The Fat Ôf The Land o^aboutdrugspofdrugs music. and wh^they^oorto whenBecause they IVe look had to Twi: M ! ïétÂWmk . j^DMXgoesoff airand into liquidation o runs DMX Inc in the US, is the liquidation means the THE RIVERDANCE EXYRAVAGANZA HAS FINALLY RETURNED TO T "r Y A 71 r i ;r LWI n M, > Jm MUSIC I ROM Tlli; SHOW » * * "l-*' • * :-0 jtî- ^ ?• RIVERDANCE EYOKES THE CELTIC PASSION AND RICH EMOTION THAT HAS CAPTIVATED AUDIENCES OF ALL AGES THE SENSATIONAL ALBUM IS OUT ON CD AND CASSETTE IN STORES FROM 28TH JULY NEWSDESK: 0171-921 59S0 or o-mail n NEWSFILE James aimsto raise MPA's profile EM(EMI Group enjoys increased market ils global share market rise share by 1% last jobthink in araising lot of thcpeople profile, think but record I still labelers ii year to a total of 19%, group chairman Sir Colin when,companics in fact, do ail wc thc bave Creative a lot work of crentsays. nt for lie. Southgate told the company's agm on Friday. Southgate impact," hc says. ing of rights, „ deliveredsaid il had satisfactory been a difficult résulta year. while but EMI HMV Music outperformed had MPA'sJames membership. also wants "The to surveypast secrc- the licensing."James is standing down as chair- the market Southgate also suggested the S35m savings didn'l bave 'ell, but theythe tee;man bis of placethe pop is beingpublishers' taken commit- by MPA ariseexpected quicker to resuit than fromoriginally its US planned, restructuring as it had should closed , Music'snight ago, Andv replacing Heath. -

Issue 10 Sunday 7 June 2020

ISSUE 10 SUNDAY 7 JUNE 2020 IN THIS ISSUE • Camilla Blackett exposes the lie that is “Over There” The wonder is how everything, • The Art of Junior absolutely everything, anyone Tomlin can name that makes our so- • Lunch with Andy called civilisation unique has a Warhol scared source – a sacred purpose. • Gnostic golf epiphanies + more Peter Kingsley, Catafalque It was the week summer officially started, although it felt like it had been summer forever. And finally, in a cruel irony only nature could orchestrate, the rain came down, ‘Like the angel come down from above’, as Steve Earle sang. Collectively, looking in horror at what’s happening ‘over there’ as Camilla Blackett powerfully reminded us in these pages, so the reckoning with a failing state and a changing country that has refused to change sharpened in focus. We have reached astonishing new depths of achievement when it comes to introspection; while even still this week at The Social Gathering marks our 10th iteration as a collaborative blog. Tom Noble, our designer, marketing guru and long-suffering Leeds fan, wanted to do something big to celebrate that moment (the 10 issues, not the introspection, that is). Perhaps, although this would belie his commitment to the hopeless West Yorkshire cause, there’s something hopeful about reaching double-figures. But how do you define BIG in a world that seems to be getting smaller? Carl, who runs the bar and whose vision led us to this place, said fuck it, let’s celebrate #23. The milestone meant little to me until I started to think about it as the week unfolded with its usual manic energy; up at 5am writing, editing, reading, communicating with authors, catching up with correspondence, procrastinating, drinking tea, sorting through records, listening to reggae, eating eggs, eventually walking the dog at 7am with my 8-year-old girl whose innocence has been a balm in the darkness then eventually ‘starting’ the day. -

A 16 Bar Cut: the History of American Musical Theatrean Original Script and Monograph Document

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2006 A 16 Bar Cut: The History Of American Musical Theatrean Original Script And Monograph Document Patrick Moran University of Central Florida Part of the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Moran, Patrick, "A 16 Bar Cut: The History Of American Musical Theatrean Original Script And Monograph Document" (2006). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 916. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/916 A 16 BAR CUT: THE HISTORY OF AMERICAN MUSICAL THEATRE An Original Script and Monograph Document by PATRICK JOHN MORAN B.A. Greensboro College, 2003 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts in the Department of Theatre in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Summer Term 2006 © 2006 Patrick John Moran ii ABSTRACT A final thesis for my Master of Fine Arts degree should encompass every aspect of the past few years spent in the class room. Therefore, as a perfect capstone to my degree, I have decided to conceive, write, and perform a new musical with my classmate Rockford Sansom entitled The History of Musical Theatre: A 16 Bar Cut. -

DNA Concerti E Ferrara Sotto Le Stelle Sono Orgogliosi Di Presentare

DNA concerti e Ferrara Sotto le Stelle sono orgogliosi di presentare KINGS OF CONVENIENCE 24 Luglio 2010 - Ferrara - Piazza Castello - Ferrara Sotto Le Stelle Dopo i due sold out di ottobre, il duo norvegese che ha incantato il mondo e raggiunto le vette delle classifiche di tutto il globo con i singoli Misread e I’d Rather Dance with You, estratti dal celebre album Riot on an Empty Street, torna in Italia per un lungo tour estivo per presentare il nuovo bellissimo album DECLARATION OF DEPENDENCE uscito per EMI alla fine del 2009. Il terzo album dei Kings Of Convenience, Declaration Of Dependence, é un disco meraviglioso per diverse ragioni. Per prima cosa, Eirik Bøe si trova ugualmente a suo agio nel parlare delle “idee serie” del disco così come nel ridere dei suoi momenti “bossanova intellettuali”, mentre Erlend Øye é chiaramente eccitato dall’aver realizzato “il disco pop più ritmico che sia mai stato fatto senza percussioni né batteria”. Secondo, non c’è nessuno che faccia dischi come loro. Per essere in grado di fare una musica così apertamente emozionale bisogna essere pronti a mettere in gioco molto di sé e a sviluppare l’abilità di essere brutalmente onesti circa le proprie idee. Declaration Of Dependence vede i Kings Of Convenience – due personalità molto diverse - afferrare il potere che hanno insieme e li sorprende ad ammettere quanto abbiano bisogno l’uno dell’altro per fare la musica che vogliono davvero fare. Un’onestà come questa non è comune nella musica pop. Toccante come vi aspettate, con brani come Second To Numb, Rule My World e 24-25, perfette come nulla che abbiano scritto finora. -

JOURNAL of MUSIC and AUDIO Issue 1, March 7, 2016

Issue 1, March 7, 2016 JOURNAL OF MUSIC AND AUDIO Copper Copper Magazine © 2016 PS Audio Inc. www.psaudio.com email [email protected] Page 2 Credits Issue 1, March 7, 2016 JOURNAL OF MUSIC AND AUDIO Publisher Paul McGowan Editor Bill Leebens Copper Columnists Seth Godin Richard Murison Dan Schwartz Bill Leebens Lawrence Schenbeck Duncan Taylor Scott McGowan Inquiries Writers [email protected] Elizabeth Newton 720 406 8946 Bill Low Boulder, Colorado Ken Micaleff USA Copyright © 2016 PS Audio International Copper magazine is a free publication made possible by its publisher, PS Audio. We make every effort to uphold our editorial integrity and strive to offer honest content for your enjoyment. Copper Magazine © 2016 PS Audio Inc. www.psaudio.com email [email protected] Page 3 Copper JOURNAL OF MUSIC AND AUDIO Issue 1 - March 7, 2016 Birth of a Child Letter from the Publisher Paul McGowan The birth of a child is always a cause for celebration. For the new parent, it's also a time of uncer- tainty and anxiety: Am I doing this right? Is THAT normal?? Creating Copper has been pretty much the same for us. There is exhilaration, the excitement of starting something completely new, of charting the course as we go. And of course, there is the desire to do everything perfectly. The first issue of Copper, now before you, requires a little by way of introduction. Copper is dedi- cated to furthering the art of home audio reproduction, and growing the community that supports it. Whether you call it Hi-Fi, hi-res, or High-End doesn't matter; such labels tend to separate and isolate people, which is exactly what we don't want to do.