Human Uniqueness and Human Dignity: Persons in Nature and The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

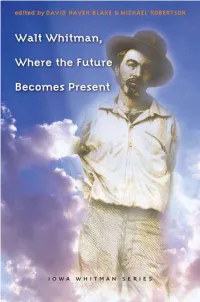

Walt Whitman, Where the Future Becomes Present, Edited by David Haven Blake and Michael Robertson

7ALT7HITMAN 7HERETHE&UTURE "ECOMES0RESENT the iowa whitman series Ed Folsom, series editor WALTWHITMAN WHERETHEFUTURE BECOMESPRESENT EDITEDBYDAVIDHAVENBLAKE ANDMICHAELROBERTSON VOJWFSTJUZPGJPXBQSFTTJPXBDJUZ University of Iowa Press, Iowa City 52242 Copyright © 2008 by the University of Iowa Press www.uiowapress.org All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Design by Richard Hendel No part of this book may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the publisher. All reasonable steps have been taken to contact copyright holders of material used in this book. The publisher would be pleased to make suitable arrangements with any whom it has not been possible to reach. The University of Iowa Press is a member of Green Press Initiative and is committed to preserving natural resources. Printed on acid-free paper issn: 1556–5610 lccn: 2007936977 isbn-13: 978-1-58729–638-3 (cloth) isbn-10: 1-58729–638-1 (cloth) 08 09 10 11 12 c 5 4 3 2 1 Past and present and future are not disjoined but joined. The greatest poet forms the consistence of what is to be from what has been and is. He drags the dead out of their coffins and stands them again on their feet .... he says to the past, Rise and walk before me that I may realize you. He learns the lesson .... he places himself where the future becomes present. walt whitman Preface to the 1855 Leaves of Grass { contents } Acknowledgments, ix David Haven Blake and Michael Robertson Introduction: Loos’d of Limits and Imaginary Lines, 1 David Lehman The Visionary Whitman, 8 Wai Chee Dimock Epic and Lyric: The Aegean, the Nile, and Whitman, 17 Meredith L. -

Icons of Survival: Metahumanism As Planetary Defense." Nerd Ecology: Defending the Earth with Unpopular Culture

Lioi, Anthony. "Icons of Survival: Metahumanism as Planetary Defense." Nerd Ecology: Defending the Earth with Unpopular Culture. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2016. 169–196. Environmental Cultures. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 25 Sep. 2021. <http:// dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781474219730.ch-007>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 25 September 2021, 20:32 UTC. Copyright © Anthony Lioi 2016. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 6 Icons of Survival: Metahumanism as Planetary Defense In which I argue that superhero comics, the most maligned of nerd genres, theorize the transformation of ethics and politics necessary to the project of planetary defense. The figure of the “metahuman,” the human with superpowers and purpose, embodies the transfigured nerd whose defects—intellect, swarm-behavior, abnormality, flux, and love of machines—become virtues of survival in the twenty-first century. The conflict among capitalism, fascism, and communism, which drove the Cold War and its immediate aftermath, also drove the Golden and Silver Ages of Comics. In the era of planetary emergency, these forces reconfigure themselves as different versions of world-destruction. The metahuman also signifies going “beyond” these economic and political systems into orders that preserve democracy without destroying the biosphere. Therefore, the styles of metahuman figuration represent an appeal to tradition and a technique of transformation. I call these strategies the iconic style and metamorphic style. The iconic style, more typical of DC Comics, makes the hero an icon of virtue, and metahuman powers manifest as visible signs: the “S” of Superman, the tiara and golden lasso of Wonder Woman. -

Television Academy Awards

2021 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot Outstanding Music Composition For A Series (Original Dramatic Score) The Alienist: Angel Of Darkness Belly Of The Beast After the horrific murder of a Lying-In Hospital employee, the team are now hot on the heels of the murderer. Sara enlists the help of Joanna to tail their prime suspect. Sara, Kreizler and Moore try and put the pieces together. Bobby Krlic, Composer All Creatures Great And Small (MASTERPIECE) Episode 1 James Herriot interviews for a job with harried Yorkshire veterinarian Siegfried Farnon. His first day is full of surprises. Alexandra Harwood, Composer American Dad! 300 It’s the 300th episode of American Dad! The Smiths reminisce about the funniest thing that has ever happened to them in order to complete the application for a TV gameshow. Walter Murphy, Composer American Dad! The Last Ride Of The Dodge City Rambler The Smiths take the Dodge City Rambler train to visit Francine’s Aunt Karen in Dodge City, Kansas. Joel McNeely, Composer American Gods Conscience Of The King Despite his past following him to Lakeside, Shadow makes himself at home and builds relationships with the town’s residents. Laura and Salim continue to hunt for Wednesday, who attempts one final gambit to win over Demeter. Andrew Lockington, Composer Archer Best Friends Archer is head over heels for his new valet, Aleister. Will Archer do Aleister’s recommended rehabilitation exercises or just eat himself to death? JG Thirwell, Composer Away Go As the mission launches, Emma finds her mettle as commander tested by an onboard accident, a divided crew and a family emergency back on Earth. -

2017 File Sesi

f e s t i v a l international l a n g u a g e festival internacionalelectronic de linguagem eletrônica o borbulhar de universos b u b b l i n g u n i v e r s e s Realização | Accomplishment FILE SÃO PAULO 2017 festival internacional de linguagem eletrônica file.org.br FILE FILE SÃO PAULO 2017 electronic l a n g u a g e international f e s t i v a l f e s t i v a l international l a n g u a g e festival internacionalelectronic de linguagem eletrônica o borbulhar de universos b u b b l i n g u n i v e r s e s Realização | Accomplishment FILE SÃO PAULO 2017 festival internacional de linguagem eletrônica file.org.br FILE FILE SÃO PAULO 2017 electronic l a n g u a g e international f e s t i v a l o borbulhar de universos b u b b l i n g u n i v e r s e s FILE SÃO PAULO 2017 festival internacional de linguagem eletrônica electronic l a n g u a g e international f e s t i v a l Dados Internacionais de Catalogação na Publicação (CIP) (Câmara Brasileira do Livro, SP, Brasil) o borbulhar de universos FILE São Paulo 2017 : Festival Internacional de Linguagem Eletrônica : o borbulhar de universos = FILE São Paulo b u b b l i n g u n i v e r s e s 2017 : Electronic Language International Festival : bubbling universes / organizadores Paula Perissinotto e Ricardo Barreto. -

Spatial Effects: Juxtapositions of Nature and Artifice in Beowulf

SPATIAL EFFECTS: JUXTAPOSITIONS OF NATURE AND ARTIFICE IN BEOWULF by Kevin D. Yeargin A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in English Middle Tennessee State University August 2014 Thesis Committee: Dr. Rhonda McDaniel, Chair Dr. Amy Kaufman ABSTRACT Critics have extensively explored the tensions in Beowulf between Christianity and Paganism, literacy and orality, and heroism and kingship, yet little work has been done toward understanding another prominent binary: nature and artifice. This thesis examines instances when the Beowulf-poet brings images of artifice and images of nature into close proximity. Along with the introduction of literacy, new technologies and ideas were suddenly thrust into Anglo-Saxon culture, and one of the ways in which the people explored these social matters was through poetry such as Beowulf. The thesis first attempts to delineate the concepts of artifice and nature as they might have been viewed from an Anglo-Saxon perspective. This enables us to see how the poet utilizes these concepts to build vibrant aesthetic effects, to construct dynamic characters, and finally to bridge the conceptual divide between his current Christian audience and their Pagan ancestors. These “spatial effects” recur with enough frequency and sophistication to suggest that they stem from intentional creative decisions. Still, many Modern English translations of Beowulf obscure their significance or ignore them altogether. If, for instance, an image appears to waver between artifice and nature, the critical inclination has been to resolve instead of embrace the tension. Contemporary scholars and translators tend to simplify what the Beowulf-poet apparently wanted to complicate. -

"Just Trying to Be Human in This Place": the Legal Education of Twenty Women

"JUST TRYING TO BE HUMAN IN THIS PLACE": THE LEGAL EDUCATION OF TWENTY WOMEN t Paula Gaber Coming back afterfifteen years out of school, I sort of thought it would be the brave new world of gender rights and racial equality that it was a politically correct world and that, at least educationally, that would be how things would operate.i During my second semester of law school, I was telling a second-year friend of mine about how unhappy I was with my law school experience. She nodded knowingly, and suggested that I read an essay that had been written by two Yale students in the 1980's. Shortly after our conversation, I found and read Catherine Weiss and Louise Melling's article entitled The Legal Education of Twenty Women,2 a study of twenty women at Yale Law School. From the first sentence of the essay, which asserts that men "made American law and American law schools by and for themselves,, 3 1 felt a tremendous sense of what can only be described as relief It was exhilarating to read a description of my own experiences in the pages of a distinguished law review. The Weiss and Melling essay both validated my feelings and showed me that I was not alone in my feelings of isolation and bewilderment in the law school environment. In an attempt to try to make sense of my own feelings of alienation, I began to read more about women in law school. The more I read, the more curious I became about the extent of the problem in my own law school class. -

The True Cost of Chevron

The True Cost of Chevron An Alternative Annual Report MAy 2009 TABLE OF CONTENTS (Unless otherwise noted, all pieces written by Antonia Juhasz) Introduction . 1. I . Chevron Corporate, Political and Economic Overview Map of Global Operations and Corporate Basics . 2. Political Influence and Connections: How Chevron Spreads its Money Around . 3. Sex, Bribes, and Paintball . .3 General James L . Jones: Chevron’s Oil Man in the White House . 4. William J . Haynes: Chevron’s In-House “Torture Lawyer” . 5. J . Stephen Griles: Current Convict—Ex Chevron Lobbyist . 5. Banking on California . 6. Squeezing Consumers at the Pump . 7. Chevron’s Hype on Alternative Energy . 8. II . The United States Alaska, Trustees for Alaska . 11. Drilling off of America’s Coasts . 13. Colorado, Utah, and Wyoming’s Oil Shale . 15. Richmond, California Refinery . 16. Pascagoula, Mississippi Refinery . 18. Perth Amboy, New Jersey Refinery, CorpWatch . 19. Chevron Sued for Massive Underground Brooklyn Oil Spill . 19. Salt Lake City Utah Refinery Lawsuit . 20. III . Around the World Angola, Mpalabanda . 21. Burma, EarthRights International . 23. Cover photo LEFT: Fire burning at Canada, Rainforest Action Network . 25. the Chevron refinery in Pascagoula, Chad-Cameroon, Antonia Juhasz edits Environmental Defense, Mississippi, photograph by Christy Pritchett ran on August 17, 2007 . Center for Environment & Development, Chadian Association Courtesy of the Press-Register 2007 for the Promotion of Defense of Human Rights . 27. © All rights reserved . Reprinted Ecuador, Amazon Watch . 29. with permission . RIGHT: Ecuadorian workers at former Texaco oil waste pit Iraq, Antonia Juhasz . 32. in Ecuador, photographed by Mitchell Anderson, January 2008 . Kazakhstan, Crude Accountability . 34. -

Cyborgs and Enhancement Technology

philosophies Article Cyborgs and Enhancement Technology Woodrow Barfield 1 and Alexander Williams 2,* 1 Professor Emeritus, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington, DC 98105, USA; [email protected] 2 140 BPW Club Rd., Apt E16, Carrboro, NC 27510, USA * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-919-548-1393 Academic Editor: Jordi Vallverdú Received: 12 October 2016; Accepted: 2 January 2017; Published: 16 January 2017 Abstract: As we move deeper into the twenty-first century there is a major trend to enhance the body with “cyborg technology”. In fact, due to medical necessity, there are currently millions of people worldwide equipped with prosthetic devices to restore lost functions, and there is a growing DIY movement to self-enhance the body to create new senses or to enhance current senses to “beyond normal” levels of performance. From prosthetic limbs, artificial heart pacers and defibrillators, implants creating brain–computer interfaces, cochlear implants, retinal prosthesis, magnets as implants, exoskeletons, and a host of other enhancement technologies, the human body is becoming more mechanical and computational and thus less biological. This trend will continue to accelerate as the body becomes transformed into an information processing technology, which ultimately will challenge one’s sense of identity and what it means to be human. This paper reviews “cyborg enhancement technologies”, with an emphasis placed on technological enhancements to the brain and the creation of new senses—the benefits of which may allow information to be directly implanted into the brain, memories to be edited, wireless brain-to-brain (i.e., thought-to-thought) communication, and a broad range of sensory information to be explored and experienced. -

Galaxy: International Multidisciplinary Research Journal the Criterion: an International Journal in English Vol

AboutUs: http://www.the-criterion.com/about/ Archive: http://www.the-criterion.com/archive/ ContactUs: http://www.the-criterion.com/contact/ EditorialBoard: http://www.the-criterion.com/editorial-board/ Submission: http://www.the-criterion.com/submission/ FAQ: http://www.the-criterion.com/fa/ ISSN 2278-9529 Galaxy: International Multidisciplinary Research Journal www.galaxyimrj.com The Criterion: An International Journal in English Vol. 12, Issue-I, February 2021 ISSN: 0976-8165 Wonder Woman: American Dc Comics Purbasa Banerjee Article History: Submitted-15/10/2020, Revised-21/02/2021, Accepted-22/02/2021, Published-28/02/2021. Abstract: Comics enlighten the fact in a light manner with a serious theme to it. Wonder Woman very much serves the purpose of the article that emphasizes on the importance of women, the value of women, the superior thought of a woman with awe-inspiring nature and characteristics that eventually demonstrate ‘Feminism’ or invaluable women around. The work is significant as the protagonist is a woman with invincible herself without any fear, facing her own world of the living and also another world where patriarchy narrates itself. There are mixed methods in the article that have been used i.e. some experiments shown in 2017 The Wonder Woman movie and some secondary data have been collected from websites and sites. The protocol used here was to proliferate the womanism as feminism and to wide open the eyes of the people about the feminine entity. And to reach the destination the theoretical angles been used giving all the information on the main character even scientifically. Ultimately, a lot of learning took place that called as results of the article. -

Views All Texts As Part of a Collective Culture from Which He May Sample

"THIS IS WHAT IT IS TO BE HUMAN": THE DRAMA AND HISTORY OF CHARLES L. MEE JR. A Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Jennifer Elissa Schlueter, B.A. ***** The Ohio State University 2003 Master's Examination Committee: Approved by Dr. Thomas Postlewait, Adviser Dr. Alan Woods Adviser Department of Theatre Copyright by Jennifer Elissa Schlueter 2003 ABSTRACT In his career, Charles L. Mee, Jr. (1938- ) has moved between the fields of history and theatre. Between 1960 and 1965, Mee participated in the Off Off Broadway movement as a playwright and a journalist. From 1966 to 1999, Mee wrote nineteen books: two memoirs, three children’s books, and fourteen histories. In 1986, Mee returned to playwriting, with his Obie-award-winning Vienna: Lusthaus. The plays Mee created after 1986 are heavily influenced by his career as a historian. His plays have taken historical events as their topic. In addition, Mee creates his scripts as collages, sampling from a variety of literary and popular texts. Further, several of Mee’s plays are rewrites of other texts, including Caucasian Chalk Circle, Orestes, and The Trojan Women. Mee claims “there is no such thing as an original play,” and thus views all texts as part of a collective culture from which he may sample. Via his website, he then returns his work, copyright-free, to the culture for further use. Mee’s battle with polio (which he contracted in 1953) has also shaped his aesthetic view. -

Factoring Humanity Progress Before He Committed Suicide? in the Case That Most Vexed Cheetah – Whether the Pregnant, 7

attempts to be human, Cheetah tries to master care about any of this in the years to come? Or is pop WWW.SFWRITER.COM both humor and the ability to make moral culture, by its very nature, utterly ephemeral? If not, Reading Group Guide judgments. Are these really the things that separate what parts of 20th Century pop culture do you think us from machines? Was Cheetah making real will endure into the next century? Factoring Humanity progress before he committed suicide? In the case that most vexed Cheetah – whether the pregnant, 7. The alien radio message from Epsilon Indi, encoded Robert J. Sawyer devoutly Catholic, comatose woman who had been on the Huneker disk, suggests that humanity should raped should have her baby – what decision would proceed with great caution in creating artificial University of Toronto psychologist you have made had you been the woman’s parents? intelligence. Do you agree? Or do you agree, as others Heather Davis succeeds in Sawyer didn’t make up this case; it really happened. have held (such as Christopher Dewdney, in his 1998 decoding alien radio messages Is mixing fact and fiction in this way appropriate? non-fiction book Last Flesh), that humanity’s destiny is received from Alpha Centauri. But to create its own silicon-based successors? her private life is falling apart, as 4. Heather Davies gets to surf the collective her grown daughter accuses memories of all of humanity, plugging into several 8. Sawyer raises several privacy issues: quantum Heather’s husband of having historical characters who interest her, including computers threaten the security of encrypted data; the abused her as a child. -

THE GENESIS PRINCIPLE of LEADERSHIP: Reclaiming and Stewarding the Long-Lost Image of God

THE GENESIS PRINCIPLE OF LEADERSHIP: Reclaiming and Stewarding the Long-Lost Image of God by Richard D. Allen, Ph.D. Professor Covenant College Lookout Mountain, Georgia 30750 Copyrighted October 31, 2002 2 Written by Richard D. Allen, Ph.D. All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, transcribed in any form by any means, including but not limited to electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or other means, without written permission of Richard D. Allen, Ph.D. October 31, 2002. The Genesis Principle of Leadership 3 Leadership is everyone’s vocation and it can be an evasion to insist it is not. Parker Palmer1 PREFACE: Leadership is a popular theme in today’s literature. The behavioral sciences, driven by mechanistic and reductionistic views of the person, provide the philosophical framework for most current notions about leadership. Many Christians, including some prominent, high-profile leaders and authors, are reprehensively ransacking prevalent leadership theories, elevating Shakespeare, Attila the Hun and others as leadership gurus. Too much of such thinking regarding leadership is left unexamined, is uncritically adopted and then “Christianized.” It is time to develop a truly biblical theory about leadership! We can no longer trim secular thinking with pious platitudes, “baptizing” current notions about leadership with a sprinkling of misapplied scripture verses. In this paper I will attempt to set forth a biblical response to the age-old question, “Are leaders born or made?” Central to this response is the biblical understanding that men and women are created in the image of God (imago Dei); that because men and women are created in His image, they possess the communicable attributes of God; and, that these attributes are the true source of leadership.