Views All Texts As Part of a Collective Culture from Which He May Sample

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Death Row U.S.A

DEATH ROW U.S.A. Summer 2017 A quarterly report by the Criminal Justice Project of the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc. Deborah Fins, Esq. Consultant to the Criminal Justice Project NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc. Death Row U.S.A. Summer 2017 (As of July 1, 2017) TOTAL NUMBER OF DEATH ROW INMATES KNOWN TO LDF: 2,817 Race of Defendant: White 1,196 (42.46%) Black 1,168 (41.46%) Latino/Latina 373 (13.24%) Native American 26 (0.92%) Asian 53 (1.88%) Unknown at this issue 1 (0.04%) Gender: Male 2,764 (98.12%) Female 53 (1.88%) JURISDICTIONS WITH CURRENT DEATH PENALTY STATUTES: 33 Alabama, Arizona, Arkansas, California, Colorado, Florida, Georgia, Idaho, Indiana, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska, Nevada, New Hampshire, North Carolina, Ohio, Oklahoma, Oregon, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas, Utah, Virginia, Washington, Wyoming, U.S. Government, U.S. Military. JURISDICTIONS WITHOUT DEATH PENALTY STATUTES: 20 Alaska, Connecticut, Delaware, District of Columbia, Hawaii, Illinois, Iowa, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, New Jersey, New Mexico [see note below], New York, North Dakota, Rhode Island, Vermont, West Virginia, Wisconsin. [NOTE: New Mexico repealed the death penalty prospectively. The men already sentenced remain under sentence of death.] Death Row U.S.A. Page 1 In the United States Supreme Court Update to Spring 2017 Issue of Significant Criminal, Habeas, & Other Pending Cases for Cases to Be Decided in October Term 2016 or 2017 1. CASES RAISING CONSTITUTIONAL QUESTIONS First Amendment Packingham v. North Carolina, No. 15-1194 (Use of websites by sex offender) (decision below 777 S.E.2d 738 (N.C. -

Mob Storms Into Tehran As Oil Halts

PAGE TWENTY-EIGHT - MANCHESTER EVENING HERALD. Manchester, Conn.. Wed.. Dec. 27. I97B other information could you Now. I’m not sure what colic sometimes benefit cage near the gallbladder give me about treatment of kind of X ray you had for from a low-fat diet. Fat region may be confused with the colic? your gallbladder, but some stimulates the gallbladder to discomfort from gallbladder What’s up In auto theft? DEAR READER - It is stones show up on an X ray contract, resulting in colic. disease. unlikely that your pain is and other don’t, depending This is not true of either pure' When such patients have Think twice about parking your car on a Boston street. HEALTH caused by gallbladder colic. upon their chemical compo protein or carbohydrates. their gallbladder removed, According to a recent survey by a'leading Insurance V^y? Because you don’t sition. I am sending you The often they don’t get relief company, Beantown has the highest auto thelt rate In the 1 " Lawrence E.Lamb.M.D. have any gallstones. Most The ones that don’t have to Health Letter number 4-9, from their symptoms be nation. attacks of gallbladder colic be visualized by X ray after Gall Stones and Gall cause the pain wasn't Here are the auto theft rates per 100.000 people as well Senator*s Win Costly 1 East Catholic Boysj Girls 1 Body Count Now 17 1 Guyana Top Headliner are caused by sudden ob taking a gallbladder dye. Bladder Disease. It will give caused by the gallbladder to as the costs ol a comprehensive theft policy on a struction of the bile duct — T his^ usi^ally done by giv you more information on begin with. -

Walt Whitman, Where the Future Becomes Present, Edited by David Haven Blake and Michael Robertson

7ALT7HITMAN 7HERETHE&UTURE "ECOMES0RESENT the iowa whitman series Ed Folsom, series editor WALTWHITMAN WHERETHEFUTURE BECOMESPRESENT EDITEDBYDAVIDHAVENBLAKE ANDMICHAELROBERTSON VOJWFSTJUZPGJPXBQSFTTJPXBDJUZ University of Iowa Press, Iowa City 52242 Copyright © 2008 by the University of Iowa Press www.uiowapress.org All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Design by Richard Hendel No part of this book may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the publisher. All reasonable steps have been taken to contact copyright holders of material used in this book. The publisher would be pleased to make suitable arrangements with any whom it has not been possible to reach. The University of Iowa Press is a member of Green Press Initiative and is committed to preserving natural resources. Printed on acid-free paper issn: 1556–5610 lccn: 2007936977 isbn-13: 978-1-58729–638-3 (cloth) isbn-10: 1-58729–638-1 (cloth) 08 09 10 11 12 c 5 4 3 2 1 Past and present and future are not disjoined but joined. The greatest poet forms the consistence of what is to be from what has been and is. He drags the dead out of their coffins and stands them again on their feet .... he says to the past, Rise and walk before me that I may realize you. He learns the lesson .... he places himself where the future becomes present. walt whitman Preface to the 1855 Leaves of Grass { contents } Acknowledgments, ix David Haven Blake and Michael Robertson Introduction: Loos’d of Limits and Imaginary Lines, 1 David Lehman The Visionary Whitman, 8 Wai Chee Dimock Epic and Lyric: The Aegean, the Nile, and Whitman, 17 Meredith L. -

The John Wayne Gacy Murders Pdf Free Download

KILLER CLOWN: THE JOHN WAYNE GACY MURDERS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Terry Sullivan,Professor Peter T Maiken | 419 pages | 01 May 2013 | Kensington Publishing | 9780786032549 | English | New York, United States Killer Clown: The John Wayne Gacy Murders by Terry Sullivan Armed with the signed search warrant, police and evidence technicians drove to Gacy's home. On their arrival, officers found Gacy had unplugged his sump pump , flooding the crawl space with water; to clear it, they simply replaced the plug and waited for the water to drain. After it had done so, evidence technician Daniel Genty entered the byfoot 8. Genty immediately shouted to the investigators that they could charge Gacy with murder, adding, "I think this place is full of kids". A police photographer then dug in the northeast corner of the crawl space, uncovering a patella. The two then began digging in the southeast corner, uncovering two lower leg bones. The victims were too decomposed to be Piest. As the body discovered in the northeast corner was later unearthed, a crime scene technician discovered the skull of a second victim alongside this body. Later excavations of the feet of this second victim revealed a further skull beneath the body. After being informed that the police had found human remains in his crawl space and that he would now face murder charges, Gacy told officers he wanted to "clear the air", adding he had known his arrest was inevitable since the previous evening, which he had spent on the couch in his lawyers' office. In the early morning hours of December 22, and in the presence of his lawyers, Gacy provided a formal statement in which he confessed to murdering approximately 30 young males—all of whom he claimed had entered his house willingly. -

Icons of Survival: Metahumanism As Planetary Defense." Nerd Ecology: Defending the Earth with Unpopular Culture

Lioi, Anthony. "Icons of Survival: Metahumanism as Planetary Defense." Nerd Ecology: Defending the Earth with Unpopular Culture. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2016. 169–196. Environmental Cultures. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 25 Sep. 2021. <http:// dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781474219730.ch-007>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 25 September 2021, 20:32 UTC. Copyright © Anthony Lioi 2016. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 6 Icons of Survival: Metahumanism as Planetary Defense In which I argue that superhero comics, the most maligned of nerd genres, theorize the transformation of ethics and politics necessary to the project of planetary defense. The figure of the “metahuman,” the human with superpowers and purpose, embodies the transfigured nerd whose defects—intellect, swarm-behavior, abnormality, flux, and love of machines—become virtues of survival in the twenty-first century. The conflict among capitalism, fascism, and communism, which drove the Cold War and its immediate aftermath, also drove the Golden and Silver Ages of Comics. In the era of planetary emergency, these forces reconfigure themselves as different versions of world-destruction. The metahuman also signifies going “beyond” these economic and political systems into orders that preserve democracy without destroying the biosphere. Therefore, the styles of metahuman figuration represent an appeal to tradition and a technique of transformation. I call these strategies the iconic style and metamorphic style. The iconic style, more typical of DC Comics, makes the hero an icon of virtue, and metahuman powers manifest as visible signs: the “S” of Superman, the tiara and golden lasso of Wonder Woman. -

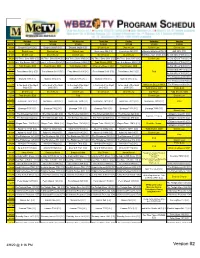

Me-TV Net Listings for 3-9-20

Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday Sunday METV 3/9/20 3/10/20 3/11/20 3/12/20 3/13/20 3/14/20 3/15/20 06:00A Dragnet 30243 {CC} Dragnet 28205 {CC} Dragnet 28206 {CC} Dietrich Law Dietrich Law Dietrich Law Dietrich Law 06:30A Dietrich Law Dietrich Law Dietrich Law I Love Lucy 056 {CC} I Love Lucy 045 {CC} The Beverly Hillbillies 6705 {CC} ALF 4012 {CC} 07:00A Dietrich Law Dietrich Law Dietrich Law Dietrich Law Dietrich Law Bat Masterson 1055ASaved {CC} by the Bell (E/I) AFQ06 {CC} <E/I-13-16> 07:30A My Three Sons 0033 {CC} My Three Sons 0034 {CC} My Three Sons 0035 {CC} My Three Sons 0036 {CC} My Three Sons 0037 {CC} Dietrich LawSaved by the Bell (E/I) AFR10 {CC} <E/I-13-16> 08:00ALeave It to Beaver 0921A {CC}Leave It to Beaver 0923A {CC}Leave It to Beaver 0926A {CC} Todd Shatkin, DDS Leave It to Beaver 0929A {CC} Saved by the Bell (E/I) AFQ14 {CC} <E/I-13-16> 08:30A Todd Shatkin, DDS Todd Shatkin, DDS Todd Shatkin, DDS What's the Buzz in WNY Todd Shatkin, DDS Saved by the Bell (E/I) AFQ10 {CC} <E/I-13-16> 09:00A Saved by the Bell (E/I) AFP13 {CC} <E/I-13-16> Perry Mason 6412 {CC} Perry Mason 6413 {CC} Perry Mason 6414 {CC} Perry Mason 6415 {CC} Perry Mason 6417 {CC} Paid 09:30A Saved by the Bell (E/I) AFQ17 {CC} <E/I-13-16> 10:00A The Flintstones 006 {CC} Matlock 8801 {CC} Matlock 8804 {CC} Matlock 8805 {CC} Matlock 8806 {CC} Matlock 8807 {CC} 10:30A The Flintstones 007 {CC} 11:00A In the Heat of the Night In the Heat of the Night In the Heat of the Night In the Heat of the Night In the Heat of the Night What's the Buzz -

The Caffe Cino

DESIGNATION REPORT The Caffe Cino Landmarks Preservation Designation Report Designation List 513 Commission The Caffe Cino LP-2635 June 18, 2019 DESIGNATION REPORT The Caffe Cino LOCATION Borough of Manhattan 31 Cornelia Street LANDMARK TYPE Individual SIGNIFICANCE No. 31 Cornelia Street in the Greenwich Village neighborhood of Manhattan is culturally significant for its association with the Caffe Cino, which occupied the building’s ground floor commercial space from 1958 to 1968. During those ten years, the coffee shop served as an experimental theater venue, becoming the birthplace of Off-Off-Broadway and New York City’s first gay theater. Landmarks Preservation Designation Report Designation List 513 Commission The Caffe Cino LP-2635 June 18, 2019 Former location of the Caffe Cino, 31 Cornelia Street 2019 LANDMARKS PRESERVATION COMMISSION COMMISSIONERS Lisa Kersavage, Executive Director Sarah Carroll, Chair Mark Silberman, Counsel Frederick Bland, Vice Chair Kate Lemos McHale, Director of Research Diana Chapin Cory Herrala, Director of Preservation Wellington Chen Michael Devonshire REPORT BY Michael Goldblum MaryNell Nolan-Wheatley, Research Department John Gustafsson Anne Holford-Smith Jeanne Lutfy EDITED BY Adi Shamir-Baron Kate Lemos McHale and Margaret Herman PHOTOGRAPHS BY LPC Staff Landmarks Preservation Designation Report Designation List 513 Commission The Caffe Cino LP-2635 June 18, 2019 3 of 24 The Caffe Cino the National Parks Conservation Association, Village 31 Cornelia Street, Manhattan Preservation, Save Chelsea, and the Bowery Alliance of Neighbors, and 19 individuals. No one spoke in opposition to the proposed designation. The Commission also received 124 written submissions in favor of the proposed designation, including from Bronx Borough President Reuben Diaz, New York Designation List 513 City Council Member Adrienne Adams, the LP-2635 Preservation League of New York State, and 121 individuals. -

The Ukrainian Weekly 1986

Іі$Ье(і by the Ukrainian National Association Inc., a fraternal non-profit association! ШrainianWeekl v ; Vol. LIV No. 34 THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY SUNDAY, AUGUST 24, 1986 25 cents Clandestine sources dispute Israel indirectly approaches USSR official Chornobyl information for help in Demjanjuk prosecution ELLICOTT CITY, Md. — The first For unexplained reasons, foreign JERSEY CITY, N.J. — Israeli offi- The card, which was used in the samvydav information has reached the radio broadcasts were difficult to pick cials have reportedly indirectly ap- United States by the Office of Special West about the accident at the Chor- up and understand within a 30-kilo- proached the Soviet Union for assis- Investigations in its proceedings against nobyl nuclear power plant in Ukraine in meter radius of the Chornobyl plant. tance in their case against John Dem- Mr. Demjanjuk, has been the subject of late April. This information disputes Thus, many listeners could not take ad- janjuk, the former Cleveland auto- much controversy. The Demjanjuk many pronouncements by the Soviet vantage of the news and advice broad- worker suspected of being "Ivan the defense contends it is a fraud and that government, reported Smoloskyp, a cast from abroad. Terrible," a guard at the Treblinka there is evidence the card was altered. quarterly published here. Although tens of thousands of death camp known for his brutality. In fact, Mark O'Connor, Mr. Dem- Following is Smoloskyp's story on school-age children were sent from Kiev The Jerusalem Post reported on janjuk's lawyer, had told The Weekly the new samvydav information. to camps on the Black Sea early, pre- August 18 that State Attorney Yona earlier this year that the original ID card According to these underground school children — who are most threat- Blattman had reportedly asked an was never examined by forensic experts. -

Jay Graydon Discography (Valid July 10, 2008)

Jay Graydon Discography (valid July 10, 2008) Jay Graydon Discography - A (After The Love Has Gone) Adeline 2008 RCI Music Pro ??? Songwriter SHE'S SINGIN' HIS SONG (I Can Wait Forever) Producer 1984 258 720 Air Supply GHOSTBUSTERS (Original Movie Soundtrack) Arista Songwriter 1990 8246 Engineer (I Can Wait Forever) Producer 2005 Collectables 8436 Air Supply GHOSTBUSTERS (Original Movie Soundtrack - Reissue) Songwriter 2006 Arista/Legacy 75985 Engineer (I Can Wait Forever) Producer Air Supply DEFINITIVE COLLECTION 1999 ARISTA 14611 Songwriter (I Can Wait Forever) Producer Air Supply ULTIMATE COLLECTION: MILLENNIUM [IMPORT] 2002 Korea? ??? Songwriter (I Can Wait Forever) BMG Entertainment 97903 Producer Air Supply FOREVER LOVE 2003 BMG Entertainment, Argentina 74321979032 Songwriter (I Can Wait Forever) FOREVER LOVE - 36 GREATEST Producer Air Supply HITS 1980 - 2001 2003 BMG Victor BVCM-37408 Import (2 CDs) Songwriter (I Can Wait Forever) Producer Air Supply PLATINUM & GOLD COLLECTION 2004 BMG Heritage 59262 Songwriter (I Can Wait Forever) Producer Air Supply LOVE SONGS 2005 Arista 66934 Songwriter (I Can Wait Forever) Producer Air Supply 2006 Sony Bmg Music, UK 82876756722 COLLECTIONS Songwriter Air Supply (I Can Wait Forever) 2006 Arista 75985 Producer GHOSTBUSTERS - (bonus track) remastered UPC: 828767598529 Songwriter (I Can Wait Forever) Producer Air Supply 2007 ??? ??? GRANDI SUCCESSI (2 CD) Songwriter (I Can Wait Forever) ULTIMATE COLLECTION Producer Air Supply 2007 Sony/Bmg Import ??? [IMPORT] [EXPLICIT LYRICS] [ENHANCED] Songwriter (I Can Wait Forever) Producer Air Supply ??? ??? ??? BELOVED Songwriter (I Can Wait Forever) Producer Air Supply CF TOP 20 VOL.3 ??? ??? ??? Songwriter (Compilation by various artists) (I Can Wait Forever) Producer Air Supply COLLECTIONS TO EVELYN VOL. -

My Beloved Is a Bass Line: Musical, De-Colonial Interventions in Song Criticism and Sacred Erotic Discourse

THE BIBLE & CRITICAL THEORY My Beloved is a Bass Line: Musical, De-colonial Interventions in Song Criticism and Sacred Erotic Discourse Heidi Epstein, University of Saskatchewan Abstract How might musical settings of the Song of Songs provide critical interventions in the politics of love? This case study builds a womanist intertextual matrix for the Song such that its amatory and horticultural language can be reinterpreted as irreducibly “de-colonial.” Reread through Chela Sandoval’s model of love, Alice Walker’s search for her foremothers’ and foresisters’ gardens, and Toni Morrison’s “commentary” on the Song (Beloved), the biblical text circulates de-colonial energies. And, given that music figures centrally in these womanists’ genealogies of love, a de-colonial reading of the Song mandates deconstruction of a subaltern musical archive within the Eurocentric discourse of sacred eroticism, a discourse that the Song sustains as an Ur-text. If the biblical female protagonist’s longing and seeking are reread as de-colonial and trickster-esque, she begets a subaltern musical family tree—audible today in the “Shulammitic” bass playing and protest singing of Meshell Ndegeocello. Key words Meshell Ndegeocello; Song of Songs; Bible and music; love; de-colonial theory; Toni Morrison; Alice Walker Introduction What meanings might be produced from the Song of Song’s amatory and horticultural language if it is read with a sense of love as irreducibly “de-colonial”? Some of these meanings shall emerge over the course of this article as I re-read the Song of Song’s imagery and its musicality in four phases through womanist intertexts by Chela Sandoval, Toni Morrison, Alice Walker, and Meshell Ndegeocello. -

Download Resume

John Himmelfarb johnhimmelfarb.com [email protected] @johnhimmelfarb Chicago, IL Spring Green, WI collections NORTHEAST Baltimore Art Museum - Baltimore, Maryland Boston Public Library Print Collection - Boston, Massachusetts Brooklyn Museum - Brooklyn, New York Danforth Museum of Art - Framingham, Massachusetts Fogg Art Museum, Harvard University - Cambridge, Massachusetts New Britain Museum of American Art - New Britain, Connecticut New York Public Library - New York, New York Rose Art Museum, Brandeis University - Waltham, Massachusetts Smithsonian American Art Museum - Washington, D.C. Vassar College Art Gallery - Poughkeepsie, New York SOUTHEAST Arkansas Art Center - Little Rock, Arkansas Asheville Museum of Art - Asheville, North Carolina Columbus Museum - Columbus, Georgia High Museum of Art - Atlanta, Georgia Huntington Museum of Art - Huntington, West Virginia Knoxville Museum of Art - Knoxville, Tennessee Montgomery Museum of Fine Arts - Montgomery, Alabama MIDWEST Albrecht-Kemper Museum - Saint Joseph, Missouri Art Institute of Chicago - Chicago, Illinois Blanden Museum of Art - Fort Dodge, Iowa Block Museum, Northwestern University - Evanston, Illinois Brauer Museum of Art, Valparaiso University - Valparaiso, Indiana Chazen Museum of Art, University of Wisconsin - Madison, Wisconsin Cleveland Museum of Art - Cleveland, Ohio Des Moines Art Center - Des Moines, Iowa Dubuque Museum of Art - Dubuque, Iowa Figge Museum of Art - Davenport, Iowa Flint Institute of Arts - Flint, Michigan Illinois State Museum - Springfield, -

Landmarks Preservation Commission November 17, 2009, Designation List 423 LP-2328

Landmarks Preservation Commission November 17, 2009, Designation List 423 LP-2328 ASCHENBROEDEL VEREIN (later GESANGVEREIN SCHILLERBUND/ now LA MAMA EXPERIMENTAL THEATRE CLUB) BUILDING, 74 East 4th Street, Manhattan Built 1873, August H. Blankenstein, architect; facade altered 1892, [Frederick William] Kurtzer & [Richard O.L.] Rohl, architects Landmark Site: Borough of Manhattan Tax Map Block 459, Lot 23 On March 24, 2009, the Landmarks Preservation Commission held a public hearing on the proposed designation as a Landmark of the Aschenbroedel Verein (later Gesangverein Schillerbund/ now La Mama Experimental Theatre Club) Building and the proposed designation of the related Landmark Site (Item No. 11). The hearing had been duly advertised in accordance with the provisions of law. Four people spoke in favor of designation, including representatives of the Municipal Art Society of New York, Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation, and Historic Districts Council. In addition, the Commission received a communication in support of designation from the Metropolitan Chapter of the Victorian Society in America. Summary The four-story, red brick-clad Aschenbroedel Verein Building, in today’s East Village neighborhood of Manhattan, was constructed in 1873 to the design of German-born architect August H. Blankenstein for this German-American professional orchestral musicians’ social and benevolent association. Founded informally in 1860, it had grown large enough by 1866 for the society to purchase this site and eventually construct the purpose-built structure. The Aschenbroedel Verein became one of the leading German organizations in Kleindeutschland on the Lower East Side. It counted as members many of the most important musicians in the city, at a time when German-Americans dominated the orchestral scene.