Five Decades Ago 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Short History of the RAF Britannia

A Short History of the RAF Britannia Birth of the Britannia Even as the Hastings was still in its prime as a 99 Squadron aircraft, thoughts were turning to a replacement that would take advantage of aeronauti- cal development and better meet the strategic air transport needs of the future. The Bristol Aircraft Britannia was to be the choice. If a conception date has to be determined for the totally military Britannia then it might be seen as July 1956 when the Chiefs of Staff set up the Bingley Committee (chaired by Rear Admiral A N C Bingley, the then Fifth Sea Lord and Deputy Chief of Naval Staff (Air)), to make recommendations on the inter-service requirements of the future air transport force. In mid-1957 the air transport force consisted of 20 Hastings, 10 Beverleys, 5 Comet 2s, 11 Vallettas. In an emergency this fleet could be supplemented with 30 Maritime Shackletons and 29 civil aircraft normally engaged in routine trooping. It was considered that this force did not match the possible demand and that an up-date was required. It is worth considering the backdrop to these deliberations. The Royal Air Force was con- cerned with the emergence of the thermo-nuclear bomb and acquiring its delivery system, the V- Force. Military emphasis had changed from the post-Korea threat of major war to the prospect of a prolonged period of maintaining delicately balanced forces to secure peace. There were clear signs that conflicts of a lesser nature were to be our concern, with a continuing commitment to global affairs. -

The Connection

The Connection ROYAL AIR FORCE HISTORICAL SOCIETY 2 The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the contributors concerned and are not necessarily those held by the Royal Air Force Historical Society. Copyright 2011: Royal Air Force Historical Society First published in the UK in 2011 by the Royal Air Force Historical Society All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing. ISBN 978-0-,010120-2-1 Printed by 3indrush 4roup 3indrush House Avenue Two Station 5ane 3itney O72. 273 1 ROYAL AIR FORCE HISTORICAL SOCIETY President 8arshal of the Royal Air Force Sir 8ichael Beetham 4CB CBE DFC AFC Vice-President Air 8arshal Sir Frederick Sowrey KCB CBE AFC Committee Chairman Air Vice-8arshal N B Baldwin CB CBE FRAeS Vice-Chairman 4roup Captain J D Heron OBE Secretary 4roup Captain K J Dearman 8embership Secretary Dr Jack Dunham PhD CPsychol A8RAeS Treasurer J Boyes TD CA 8embers Air Commodore 4 R Pitchfork 8BE BA FRAes 3ing Commander C Cummings *J S Cox Esq BA 8A *AV8 P Dye OBE BSc(Eng) CEng AC4I 8RAeS *4roup Captain A J Byford 8A 8A RAF *3ing Commander C Hunter 88DS RAF Editor A Publications 3ing Commander C 4 Jefford 8BE BA 8anager *Ex Officio 2 CONTENTS THE BE4INNIN4 B THE 3HITE FA8I5C by Sir 4eorge 10 3hite BEFORE AND DURIN4 THE FIRST 3OR5D 3AR by Prof 1D Duncan 4reenman THE BRISTO5 F5CIN4 SCHOO5S by Bill 8organ 2, BRISTO5ES -

World Bank Document

Document de La Banque Mondiale IFILE COp<1 A N'UTlLlSER QU'A DES FINS OFFICIELLES Public Disclosure Authorized Rapport No. 3867-DI RAPPORT D'EVALUATION Public Disclosure Authorized DJIBOUTI PROJET D'ENTRETIEN ROUTIER Public Disclosure Authorized 24 septembre 1982 Division des transports 1 Bureau regional Afrique de l'Est Public Disclosure Authorized TRADUCTION NON-OFFICIELLE A TITRE D'INFORMATlON e pre5.ent document fait l'objE't d'une diffu5.ion reslreinte, et ne peut (:Ire utilise par ~es destinataires que dans I'exereh:e de leurs fonetions officieJles. Sa teneur ne peut etre DaUllrement divulguee sans I'aulorisation de la Banque Mondiale. ~ d TAUX DE CHANGE Unite monetaire = Franc de Djibouti (FD) $ EU 1 = FD 175 POlDS ET ~lEStJRES Systeme met rique SIGLES ET ABREVIATIONS FED Fonds europeen de developpement FAC Fonds d'aide et de cooperation (France) DTP Direction des travaux publics TRE Taux de rentabilite economique EXERCICE 1er janvier - 31 decembre A N'UTILISER QU'A DES FINS OFFICIELLES DJIBOUTI PROJET D'ENTRETIEN ROUTIER RAPPORT D'EVALUATION Table des matieres I.. LE SECTEUR DES TRANSPORTS ...................................... 1 A. Le cadre economique ....................................... 1 B. Le reseau des transports - Generalites ..... ............... 1 C. Le sous·secteur routier ..................... :.... ... ...... 3 D. Planification et financement des transports ... ............ 9 E. Politique de developpement des routes............ ......... 10 II. LE PROJET ...................................................... 11 A. Objectifs ................................................. 11 B. Description du projet ..................................... 11 C. Estimations des couts du projet et financement .... ..... ... 14 D. Execution du projet et passation des marches.............. 15 E. Decaissements ............................................. 17 F, Criteres d'etablissement des comptes et des rapports...... 19 G. Impact sur l'environnement ............................... -

And Then… (Accounts of Life After Halton 1963-2013)

And Then… (Accounts of Life after Halton 1963-2013) Compiled & Edited by Gerry (Johnny) Law And Then… CONTENTS Foreword & Dedication 3 Introduction 3 List of aircraft types 6 Whitehall Cenotaph 249 St George’s 50th Anniversary 249 RAF Halton Apprentices Hymn 251 Low Flying 244 Contributions: John Baldwin 7 Tony Benstead 29 Peter Brown 43 Graham Castle 45 John Crawford 50 Jim Duff 55 Roger Garford 56 Dennis Greenwell 62 Daymon Grewcock 66 Chris Harvey 68 Rob Honnor 76 Merv Kelly 89 Glenn Knight 92 Gerry Law 97 Charlie Lee 123 Chris Lee 126 John Longstaff 143 Alistair Mackie 154 Ivor Maggs 157 David Mawdsley 161 Tony Meston 164 Tony Metcalfe 173 Stuart Meyers 175 Ian Nelson 178 Bruce Owens 193 Geoff Rann 195 Tony Robson 197 Bill Sandiford 202 Gordon Sherratt 206 Mike Snuggs 211 Brian Spence 213 Malcolm Swaisland 215 Colin Woodland 236 John Baldwin’s Ode 246 In Memoriam 252 © the Contributors 2 And Then… FOREWORD & DEDICATION This book is produced as part of the 96th Entry’s celebration of 50 years since Graduation Our motto is “Quam Celerrime (With Greatest Speed)” and our logo is that very epitome of speed, the Cheetah, hence the ‘Spotty Moggy’ on the front page. The book is dedicated to all those who joined the 96th Entry in 1960 and who subsequently went on to serve the Country in many different ways. INTRODUCTION On the 31st July 1963 the 96th Entry marched off Henderson Parade Ground marking the conclusion of 3 years hard graft, interspersed with a few laughs. It also marked the start of our Entry into the big, bold world that was the Royal Air Force at that time. -

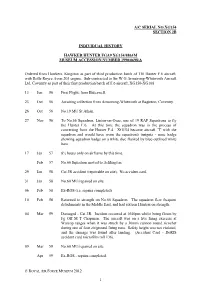

A/C Serial No.Xg154 Section 2B

A/C SERIAL NO.XG154 SECTION 2B INDIVIDUAL HISTORY HAWKER HUNTER FGA9 XG154/8863M MUSEUM ACCESSION NUMBER 1990/0698/A Ordered from Hawkers, Kingston as part of third production batch of 110 Hunter F.6 aircraft, with Rolls-Royce Avon 203 engine. Sub-contracted to Sir W G Armstrong-Whitworth Aircraft Ltd, Coventry as part of their first production batch of F.6 aircraft, XG150-XG168 13 Jun 56 First Flight, from Bitteswell. 23 Oct 56 Awaiting collection from Armstrong-Whitworth at Baginton, Coventry. 26 Oct 56 No.19 MU St Athan. 27 Nov 56 To No.66 Squadron, Linton-on-Ouse, one of 19 RAF Squadrons to fly the Hunter F.6. At this time the squadron was in the process of converting from the Hunter F.4. XG154 became aircraft `T' with the squadron and would have worn the squadron's insignia - nose badge showing squadron badge on a white disc flanked by blue-outlined white bars. 17 Jan 57 8½ hours only on airframe by this time. Feb 57 No.66 Squadron moved to Acklington. 29 Jan 58 Cat 3R accident (repairable on site). No accident card. 31 Jan 58 No.60 MU/repaired on site. 06 Feb 58 Ex-ROS (i.e. repairs completed). 10 Feb 58 Returned to strength on No.66 Squadron. The squadron flew frequent detachments in the Middle East, and had sixteen Hunters on strength. 04 Mar 59 Damaged - Cat 3R. Incident occurred at 1640pm whilst being flown by Fg Off M T Chapman. The aircraft was on a live firing exercise at Warcop ranges when it was struck by a 30mm cannon round ricochet during one of four air/ground firing runs. -

Battle of Britain Dining in Night

INSIGHT BATTLE OF BRITAIN DINING IN NIGHT INSIGHTMAGAZINE 1 2 INSIGHTMAGAZINE INSIGHTMAGAZINE 3 INSIGHT Issue 5 2013 From the Editor… From Brammer to Bremner… There may have been some who have taken the time to minor confusion over the present articles highlighting Brammer/Bremner handover the diverse activities of service of the editor role of the Insight personnel, families and the Magazine, but I clearly have a community. The Insight team lot to thank Squadron Leader have been working hard to EDITORIAL TEAM: Brammer for, the last editorial ensure the magazine reflects [email protected] for a start. I am grateful for the spectrum of activities at RAF the vibrant and professional Waddington and we are always External Email: Use personal email addresses listed magazine that he and his team keen to receive articles, so please Tel: 01522 720271 (6706 Ext No.) have developed and hope to if you are organising an event or Editor: continue to ensure it meets the activity, send us some pictures needs of RAF Waddington and and an article, to let everyone Sqn Ldr Stewart Bremner the local community. know what you are up to. [email protected] Deputy Editor: As we enjoy the last few days Looking forward, there are of Summer it is clear from the more changes coming to the (Flt Lt) Heather Constantine wide range of articles that we Insight editorial team and we [email protected] have received, that the Station are all keen to ensure that the Assistant Deputy Editors: has had an extremely busy but magazine meets the needs rewarding few months. -

The Emergency Develops 1St Battalion Lancashire Regiment

The Aden Emergency 1963 - 1967 The Aden Emergency, also known as the Radfan Uprising, was an insurgency against the Occupying Forces of the former British Empire in the Protectorate of South Arabia, which now forms part of Yemen. The uprising began on 14th October 1963 with the throwing of a grenade at British High Commissioner Sir Kennedy Trevaskis, which took place as he arrived at Khormaksar Airport to catch a London-bound flight. The grenade killed a woman and injured fifty other people. On that day, a state of emergency was declared in Aden. The Emergency Develops Anti-British guerrilla groups with varying political objectives began to coalesce into two larger, rival organisations: first the Egyptian-supported National Liberation Front (NLF) and then the Front for the Liberation of Occupied South Yemen (FLOSY), who attacked each other as well as the British. Between 1963 and 1967 the NLF and FLOSY waged a continuous campaign against British forces in Aden, relying largely on grenade attacks mainly focused on killing off-duty British officers and policemen. By 1965, the RAF station RAF Khormaksar was operating nine squadrons. These included transport units with helicopters and a number of Hawker Hunter fighter bomber aircraft. 1st Battalion Lancashire Regiment (Prince of Wales's Volunteers) The 1st Battalion Lancashire Regiment (Prince of Wales's Volunteers) (PWV) were deployed in South Arabia from January to October 1967. Local St Helens soldiers served in Aden among the ranks of the 1st Battalion Lancashire Regiment (PWV). They arrive at Radfan Camp in January 1967 and were immediately drawn into action. -

Royal Air Force Historical Society Journal 18

ROYAL AIR FORCE HISTORICAL SOCIETY JOURNAL 18 2 The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the contributors concerned and are not necessarily those held by the Royal Air Force Historical Society. First Published in the UK in 1998 Copyright © 1998: Royal Air Force Historical Society. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without the permission from the Publisher in writing. ISSN 1361-4231 Printed by Fotodirect Ltd Enterprise Estate, Crowhurst Road Brighton, East Sussex BN1 8AF Tel 01273 563111 3 CONTENTS Page SOME REFLECTIONS – Rt Hon Lord Merlyn-Rees 6 ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING 10th June 1997 19 SOUTH ARABIA AND THE WITHDRAWAL FROM ADEN 24 AIRMAN’S CROSS – Postscript 100 AIR CHIEF MARSHAL SIR DENIS SMALLWOOD 103 BOOK REVIEWS 106 CORRESPONDENCE 121 NOTICES 124 4 ROYAL AIR FORCE HISTORICAL SOCIETY President: Marshal of the Royal Air Force Sir Michael Beetham GCB CBE DFC AFC Vice-President: Air Marshal Sir Frederick Sowrey KCB CBE AFC Committee Chairman: Air Vice-Marshal N B Baldwin CB CBE General Secretary: Wing Commander C G Jefford MBE BA Membership Secretary: Dr Jack Dunham PhD CPsychol AMRAeS Treasurer: Desmond Goch Esq FCAA Members: *J S Cox BA MA *Dr M A Fopp MA FMA FIMgt Group Captain J D Heron OBE *Group Captain S W Peach BA RAF Air Commodore H A Probert MBE MA Editor, Publications Derek H Wood Esq AFRAeS Publications Manager Roy Walker Esq ACIB *Ex officio 5 INTRODUCTION BY SOCIETY CHAIRMAN Air Vice-Marshal Baldwin after the 11th AGM Ladies and gentlemen it is a pleasure to welcome as our guest this evening Lord Merlyn-Rees, an ex-Secretary of State for Northern Ireland and Home Secretary and, just as important from our point of view, an ex RAF squadron leader. -

Nairobi Airport Annual Report 1965 ~·

REPUBLIC OF KENYA NAIROBI AIRPORT ANNUAL REPORT 1965 ~·,. 1. D. E. P. rii~ lf~·l CENTRE ··~".~-'1 DE DOCUMENTATION Three Shillings - 1966 . .' NAIROBI AIRPORT ANNUAL REPORT 196S 1. D. E. P. CENTRE DE DOCUMENTATION CONTENTS INTRODUCTION-REVIEW OF THE YEAR Part !-Sections PAGE 1. Operations .. 2 2. Aerodrome Fire Service 6 3. Business Management 7 4. Security Service 8 5. Information Service 9 6. Additional Kenya Government Services JO 7. East African Common Services Organization .. 12 Part II-Appendices 1 Senior Staff of the Department 14 TI Airline Operating Companies and their Representatives .. J4 11I Aircraft Movements J5 IV Passeogers Handled 16 V Mail J6 VI Freight .. 17 VII Aviation Fuel Uplift 18 Vlll Waving Base Visitors 19 IX Diversions Due to Weather 19 x Delayed Arrivais Due to Weather 20 Xl Delayed Departures Due to Weather 20 XII Meteorological Data .. 21 Xlli General Information .. 23 XIV Radio Facilities and Navigatiooal Aids 26 XV Air Distances from Nairobi Airport 29 XVI Legislation 30 NAIROBI AffiPORT ANNUAL REPORT 1965 INTRODUCTION Rcvicw of the Y car T he rate of increase in the Airport's actüvities which has been steadily growing in the previous years was main tained in 1965. D uring the year, one more airline, namely, Pan-American World Airways was added to the n umber of heavy jet operators using Nairobi Airport. The introduction of a DC.S jet airliner by this new company, providing non-stop scheduled fli ghts between Lagos and Nairobi, opened the fi rst direct air lin k between Kenya and West Africa. This is a faci lity which has been longed for by many travellers in the past. -

215183076.Pdf

IDENTIFICATION AND ANALYSIS OF INTERNATIONAL TERRORISM TRENDS ON AERONAUTICAL SECURITY By CHRIS ANTHONY HAMILTON Bachelor of Science Saint Louis University Saint Louis, Missouri 1987 Master of Science Central Missouri State University Warrensburg, Missouri 1991 Education Specialist Central Missouri State University Warrensburg, Missouri 1994 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF EDUCATION May, 1996 COPYRIGHT By Chris Anthony Hamilton May, 1996 IDENTIFICATION AND ANALYSIS OF INTERNATIONAL TERRORISM TRENDS ON AERONAUTICAL SECURITY Thesis Approved: Dean of the Graduate College ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to take this opportunity to express my sincere appreciation to all those who, support, guidance, and sacrificed time made my educational experience at Oklahoma State University a successful one. First, I would like to thank my doctoral committee chairman, Dr. Cecil Dugger for his guidance and direction throughout my doctoral program. Dr. Dugger is a unique individual for which I have great respect not only as a mentor but also as good and supportive friend. I would also like to thank my dissertation advisor Dr. Steven Marks, for his support and impute in my academic life at Oklahoma State University. I would also like to thank the Dr. Kenneth Wiggins, Head, Department of Aviation and Space Education for his continue and great support in many ways, that without, I will have never completed my educational goals. Finally, I would like to thank Dr. Deke Johnson as my doctoral committee member, that has always a kind and wise word to get me through difficult days. -

A History of Modern Yemen

A HISTORY OF MODERN YEMEN PAUL DRESCH University of Oxford The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge, United Kingdom The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge , UK http://www.cup.cam.ac.uk West th Street, New York, –, USA http://www.cup.org Stamford Road, Oakleigh, Melbourne , Australia Ruiz de Alarcón , Madrid, Spain © Cambridge University Press This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published Printed in the United Kingdom at the University Press, Cambridge Typeface Monotype Baskerville /. pt System QuarkXPress™ [] A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloguing in Publication data Dresch, Paul. A history of modern Yemen / Paul Dresch. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. Yemen–History–th century. I. Title. .–dc - hardback paperback Contents List of illustrations page ix List of maps and figures xi Preface and acknowledgements xiii List of abbreviations xvii . Turkey, Britain and Imam Yah·ya¯: the years around Imperial divisions Premodern Yemen Political connections Forms of life .Yah·ya¯ and the British: – Control of Yemen Aden’s hinterland and H· ad·ramawt A geographical intersection The dynastic state Modernist contradictions The coup of . A new form of politics: the s Changes in the South The Aden hinterland Ah·mad’s domain The new politics Cairo and Sanaa Constitutions and revolution . Revolutions and civil wars: the s Revolution in the North Armed struggle in the South Aden as political focus ¨ Abd al-Na¯s·ir and Yemen The end of the British in the South vii viii Contents The end of the Egyptians in the North Consolidation of two states . -

A/C Serial No.Xg154 Section 2B

A/C SERIAL NO.XG154 SECTION 2B INDIVIDUAL HISTORY HAWKER HUNTER FGA9 XG154/8863M MUSEUM ACCESSION NUMBER 1990/0698/A Ordered from Hawkers, Kingston as part of third production batch of 110 Hunter F.6 aircraft, with Rolls-Royce Avon 203 engine. Sub-contracted to Sir W G Armstrong-Whitworth Aircraft Ltd, Coventry as part of their first production batch of F.6 aircraft, XG150-XG168 13 Jun 56 First Flight, from Bitteswell. 23 Oct 56 Awaiting collection from Armstrong-Whitworth at Baginton, Coventry. 26 Oct 56 No.19 MU St Athan. 27 Nov 56 To No.66 Squadron, Linton-on-Ouse, one of 19 RAF Squadrons to fly the Hunter F.6. At this time the squadron was in the process of converting from the Hunter F.4. XG154 became aircraft `T' with the squadron and would have worn the squadron's insignia - nose badge showing squadron badge on a white disc flanked by blue-outlined white bars. 17 Jan 57 8½ hours only on airframe by this time. Feb 57 No.66 Squadron moved to Acklington. 29 Jan 58 Cat 3R accident (repairable on site). No accident card. 31 Jan 58 No.60 MU/repaired on site. 06 Feb 58 Ex-ROS (i.e. repairs completed). 10 Feb 58 Returned to strength on No.66 Squadron. The squadron flew frequent detachments in the Middle East, and had sixteen Hunters on strength. 04 Mar 59 Damaged - Cat 3R. Incident occurred at 1640pm whilst being flown by Fg Off M T Chapman. The aircraft was on a live firing exercise at Warcop ranges when it was struck by a 30mm cannon round ricochet during one of four air/ground firing runs.