CLR James's Early Thoughts on American Civilisation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Black Internationalism and African and Caribbean

BLACK INTERNATIONALISM AND AFRICAN AND CARIBBEAN INTELLECTUALS IN LONDON, 1919-1950 By MARC MATERA A Dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-New Brunswick Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in History Written under the direction of Professor Bonnie G. Smith And approved by _______________________ _______________________ _______________________ _______________________ New Brunswick, New Jersey May 2008 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Black Internationalism and African and Caribbean Intellectuals in London, 1919-1950 By MARC MATERA Dissertation Director: Bonnie G. Smith During the three decades between the end of World War I and 1950, African and West Indian scholars, professionals, university students, artists, and political activists in London forged new conceptions of community, reshaped public debates about the nature and goals of British colonialism, and prepared the way for a revolutionary and self-consciously modern African culture. Black intellectuals formed organizations that became homes away from home and centers of cultural mixture and intellectual debate, and launched publications that served as new means of voicing social commentary and political dissent. These black associations developed within an atmosphere characterized by a variety of internationalisms, including pan-ethnic movements, feminism, communism, and the socialist internationalism ascendant within the British Left after World War I. The intellectual and political context of London and the types of sociability that these groups fostered gave rise to a range of black internationalist activity and new regional imaginaries in the form of a West Indian Federation and a United West Africa that shaped the goals of anticolonialism before 1950. -

Island People

ISLAND PEOPLE [BIBLIOGRAPHY & FURTHER READING] JOSHUA JELLY-SCHAPIRO Island People: Bibliography and Further Reading www.joshuajellyschapiro.com ISLAND PEOPLE The Caribbean and the World By Joshua Jelly-Schapiro [Knopf 2016/Canongate 2017] Bibliography & Further Reading The direct source materials for Island People, and for quotations in the text not deriving from my own reporting and experience, are the works of history, fiction, film and music, along with primary documents from such archiVes as the West Indiana and Special Collections division at the University of the West Indies library in St. Augustine, Trinidad, enumerated in the “Notes” at the back of the book. But as essential to its chapters’ background, and to my explorations of indiVidual islands and their pasts, is a much larger body of literature—the wealth of scholarly and popular monographs on Antillean history and culture that occupy students and teachers in the burgeoning academic field of Caribbean Studies. What follows is a distilled account, more suggestiVe than comprehensiVe, of that bibliography’s essential entries, focusing on those books and other sources informing the stories and ideas contained in my book—and that comprise something like a list of Vital reading for those wishing to go further. Emphasis is here giVen to works in English, and to foreign-language texts that have been published in translation. Exceptions include those Spanish- and French- language works not yet published into English but which form an essential part of any good library on the islands in question. 1 Island People: Bibliography and Further Reading www.joshuajellyschapiro.com Introduction: The Caribbean in the World Start at the beginning. -

Uptown Conversation : the New Jazz Studies / Edited by Robert G

uptown conversation uptown conver columbia university press new york the new jazz studies sation edited by robert g. o’meally, brent hayes edwards, and farah jasmine griffin Columbia University Press Publishers Since 1893 New York Chichester, West Sussex Copyright © 2004 Robert G. O’Meally, Brent Hayes Edwards, and Farah Jasmine Griffin All rights reserved Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Uptown conversation : the new jazz studies / edited by Robert G. O’Meally, Brent Hayes Edwards, and Farah Jasmine Griffin. p. cm. Includes index. ISBN 0-231-12350-7 — ISBN 0-231-12351-5 1. Jazz—History and criticism. I. O’Meally, Robert G., 1948– II. Edwards, Brent Hayes. III. Griffin, Farah Jasmine. ML3507.U68 2004 781.65′09—dc22 2003067480 Columbia University Press books are printed on permanent and durable acid-free paper. Printed in the United States of America c 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 p 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 contents Acknowledgments ix Introductory Notes 1 Robert G. O’Meally, Brent Hayes Edwards, and Farah Jasmine Griffin part 1 Songs of the Unsung: The Darby Hicks History of Jazz 9 George Lipsitz “All the Things You Could Be by Now”: Charles Mingus Presents Charles Mingus and the Limits of Avant-Garde Jazz 27 Salim Washington Experimental Music in Black and White: The AACM in New York, 1970–1985 50 George Lewis When Malindy Sings: A Meditation on Black Women’s Vocality 102 Farah Jasmine Griffin Hipsters, Bluebloods, Rebels, and Hooligans: The Cultural Politics of the Newport Jazz Festival, 1954–1960 126 John Gennari Mainstreaming Monk: The Ellington Album 150 Mark Tucker The Man 166 John Szwed part 2 The Real Ambassadors 189 Penny M. -

When Britain Loved Rastafari: Englishness, Britishness and Ethiopianism"

Rasta Ites home Rastafari Movement UK Ites Zine “When Britain Loved RasTafari: Englishness, Britishness and Ethiopianism" At talk given by Dr. Robbie Shilliam: Reader in International Relations at Queen Mary University of London to the Anglo-Ethiopian Society and guests at SOAS, London UK, 22nd July 2015 This talk grew out of research collectively done for the Rastafari: Majesty and the Movement exhibition ************************************************************************** “This country is honoured by the emperor having taken up his residence here. Ten righteous men would have saved Sodom; I feel the emperor is one of the comparatively few who may save Britain.” So says one English commentator in the summer of 1936. The emperor in question is Qadamawi Haile Selassie of Ethiopia. The occasion: his arrival in England after the fascist Italian occupation of his homeland. But why would Britain need to be saved? Well, when, in 1935, Italy invaded Ethiopia – both sovereign members of the League of Nations - Britain promised to support this victim of fascist aggression. But Britain did not support Ethiopia – or international law. Instead, the government allowed Italy to consolidate its place in the African sun. Sylvia Pankhurst’s letters, her newspaper – New Times and Ethiopia News - as well as the general press of the day, suggest that many white Britons and Black subjects from British Caribbean and African colonies took issue with this duplicity. In short, Britain needed to be saved from its own perfidiousness. What did it mean to be British in this colonial era? What did it mean to belong to this perfidious empire? A number of things. -

The Construction of an Essentialist Mixed-Race' Identity in the Anglophone Caribbean Novel

THE CONSTRUCTION OF AN ESSENTIALIST MIXED-RACE' IDENTITY IN THE ANGLOPHONE CARIBBEAN NOVEL 1914 -1998 A thesis submitted to the University of London in part fulfilment of the requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Melissa PERSAUD Goldsmiths College University of London Supervisor: Dr Helen Carr March 2000 ýý-ýýý ti r1 ,ý ý. ABSTRACT This thesis examines the portrayal of the 'mixed-race' person in twentieth-century Caribbean literature. The premise that their portrayal has been limited by essentialised racial stereotypes is investigated and the conclusion is reached that these stereotypes have been founded in nineteenth century theories of racial hybridity. The development of this racial theory is explored and reveals that the concept of hybridity was generated through imperialistic and colonial endeavours to support a policy of racial subjugation predicated by European economic desire to exploit non-white peoples. In the Caribbean this took the form of African slavery, and the need to keep the 'races' separate and unequal under this system led to the demonisation of 'mixed-race' people of African and European descent. Despite attempts to prevent the proliferation of a 'mixed-race' population, their increasing numbers led to further plantocratic strategies to divide the 'mixed-race' and black population in order to maintain white socio-economic supremacy. This thesis finds that the literary construction of 'mixed-race' identity has been grounded in a biologised fallacy of `hybridity'. Despite recent attempts to appropriate the term `hybridity' as a cultural metaphor, hybridity itself remains entrenched in nineteenth century notions of absolute racial difference. The biological concept of `mixed-race' degeneracy coupled with the white engineered racial divisions within Caribbean society has left the 'mixed-race' person in an ambivalent position. -

A Sidelong Glance: the Practice of African Diaspora Art History in the United States

In This Issue & Katy Siegel Reconstruction Centennial Essay ( Krista Thompson Table of A Sidelong Glance: The Practice of African Diaspora Art History in the United States Contents Forum: Performance, Live or Dead #$ Amelia Jones, Introduction #+ Ron Athey, Getting It Right . Zooming Closer "' Sven Lütticken, Performing Time "& Sharon Hayes, The Not-Event "( Sophia Yadong Hao, Memory Is Not Transparent &! Branislav Jakovljević, On Performance Forensics: The Political Economy of Reenactments && William Pope.L, Canary in the Coal Mine &+ Helena Reckitt, To Make Time Appear Features (" Miwako Tezuka Experimentation and Tradition: The Avant-Garde Play Pierrot Lunaire by Jikken Kōbō and Takechi Tetsuji +( Sarah Kanouse Take It to the Air: Radio as Public Art Reviews '!! Lisa Florman on Kenneth Silver, ed., Chaos and Classicism: Art in France, Italy, and Germany, !"!#–!"$%, and the exhibition Chaos and Classicism: Art in France, Italy, and Germany, !"!#–!"$%, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York and Bilbao, $!'!–''; Robert Sli.in on Elisabeth Sussman and Lynn Zelavanksy, eds., Paul Thek: Diver, A Retrospective, and the exhibition Paul Thek: Diver, A Retrospective, Whitney Museum of American Art, $!'!–'', and Harald Falckenberg and Peter Weibel, eds., Paul Thek: Artist’s Artist; Jaleh Mansoor on Rosalyn Deutsche, Hiroshima after Iraq: Three Studies in Art and War; Lara Weibgen on Victor Tupitsyn, The Museological Unconscious: Communal (Post)Modernism in Russia, Boris Groys, History Becomes Form: Moscow Conceptualism, and Matthew Jesse Jackson, The Experimental Group: Ilya Kabakov, Moscow Conceptualism, Soviet Avant-Gardes ''# Letters Anne-Louis Girodet-Trioson, C[itizen] How one is seen (as black) and therefore, what one sees (in a white world) is always already crucial to Jean-Baptiste Belley, Ex-Representative of one’s existence as an Afro-American. -

History of Liberation + Nigeria Tamils + Tuna + West Papua + Book

Liberation Volume 57 No1 2014 International Womens Day Issue £1.50 Also Inside – History of Liberation + Nigeria Tamils + Tuna + West Papua + Book Review JOURNAL OF LIBERATION, FORMERLY THE MOVEMENT FOR COLONIAL FREEDOM Liberation EDITORIAL Volume 57 No 1 March 2014 adopted 43 restrictions on ac- the fast-food industry. Strikes ISSN 0024 1873 cess to abortion in the first half at places like McDonald’s, 75-77 St John Street, London, EC1M 4NN of 2013 — as many as enacted Burger King and Wendy’s have Phone & Fax 44 0207 324 2498 & 2489 in all of 2012. mushroomed from seven cities On June 18, the House of a month ago to about 60 cities E-mail [email protected] Representatives passed a bill on Aug. 29. And it’s women, Website (228-196) that would restrict often single mothers, who are http://www.liberationorg.co.uk abortions after 22 weeks on leading chants like “We can’t the unscientific supposition survive on $7.25!” Women are Editorial that a fetus feels pain at that also demanding living wages E-mail [email protected] point in its development. Since and benefits at Walmart. Phone & Fax 44 020 7229 5831 it is a direct challenge to the Taking note of that and of the 1973 Supreme Court decision fact that women are now 49 Editor - George Anthony. legalizing abortion, the bill will percent of the workforce, with Other than the editorial, the opinions in the articles never be passed by the Senate. an increasing number being inside are not necessarily those of Liberation. -

Introduction Diaspora and the Localities of Race

Introduction Diaspora and the Localities of Race Minkah Makalani Work theorizing the African diaspora has sought to identify its defining characteristics, map out lines of continuity between its geographic seg- ments, and outline methodological approaches to studying the dispersion of African descended populations. This work has resulted in studies of cultural exchange, migration, the social structure of various Afro-diasporic communities, as well as political activism within those communities.1 Recent scholarship, however, has devoted greater analytical attention to the question of difference — how diasporas emerge through “relations of difference,” thus opening up the necessary space for thinking about difference as a central feature of diaspora rather than a problem one must solve.2 Difference draws attention to how diaspora, as a social for- mation, is simultaneously framed by relationships of domination and is itself a structured hierarchy. Thus, the claim by Kachig Tölölyan that the African diaspora is exceptional precisely because of the history of racialization in this particular formation suggests the need for more work on racial difference in diaspora.3 What stands out most about the African diaspora is not merely that the process of racialization was central to and concomitant with dispersion, but that dispersion involved multiple racial formations that rendered large segments of African-descended popula- tions in places like the Dominican Republic, Brazil, Lusophone Africa, and Europe something other than black. The unique racial formations within which these populations exist complicate thinking about diaspora as a community and call into question the assumption of a correspon- dence between African diaspora and blackness. Indeed, work on the dis- similarities between the blackness of Africans, African Caribbeans, and Social Text 98 • Vol. -

Mariner, Renegade, Castaway: Chris Braithwaite, Seamen's Organiser and Pan-Africanist

This is a repository copy of Mariner, Renegade, Castaway: Chris Braithwaite, seamen’s organiser and Pan-Africanist. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/90062/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Hogsbjerg, CJ (2011) Mariner, Renegade, Castaway: Chris Braithwaite, seamen’s organiser and Pan-Africanist. Race and Class, 53 (2). pp. 36-57. ISSN 0306-3968 https://doi.org/10.1177/0306396811414114 © 2011 Institute of Race Relations. This is an author produced version of a paper published in Race and Class. Uploaded in accordance with the publisher's self-archiving policy. Reuse Unless indicated otherwise, fulltext items are protected by copyright with all rights reserved. The copyright exception in section 29 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 allows the making of a single copy solely for the purpose of non-commercial research or private study within the limits of fair dealing. The publisher or other rights-holder may allow further reproduction and re-use of this version - refer to the White Rose Research Online record for this item. Where records identify the publisher as the copyright holder, users can verify any specific terms of use on the publisher’s website. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Christian Høgsbjerg1 Mariner, renegade, castaway: Chris Braithwaite, seamen’s organiser and Pan- Africanist Introduction In 1945, the British socialist feminist novelist Ethel Mannin, a ‘determined collector of “interesting people”’, penned a satirical novel, Comrade O Comrade, reminiscing about the politics of the British far-Left during the 1930s.2 Subtitled ‘low- down on the Left’, Mannin noted that ‘not all the characters in this story are entirely fictitious’. -

Printing the West Indies: Literary Magazines and the Anglophone Caribbean 1920S-1950S Claire Catherine Irving

Printing the West Indies: Literary magazines and the Anglophone Caribbean 1920s-1950s Claire Catherine Irving Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Newcastle University School of English Literature, Language and Linguistics December 2015 Printing the West Indies: Literary magazines and the Anglophone Caribbean 1920s-1950s Abstract This thesis uncovers a body of literary magazines previously seen as peripheral to Caribbean literature. Drawing on extensive archival research, it argues for the need to open up the critical consensus around a small selection of magazines (Trinidad, The Beacon, Bim and Kyk-over-al), to consider a much broader and more varied landscape of periodicals. Covering twenty-eight magazines, the thesis is the first sustained account of a periodical culture published between the 1920s and 1950s. The project identifies a broad-based movement towards magazines by West Indians, informed and shaped by a shared aspiration for a West Indian literary tradition. It identifies the magazines as a key forum through which the West Indian middle classes contributed to and negotiated the process of cultural decolonisation which paralleled the political movement to independence in the 1960s. Chapter One explores the broad ways in which the magazines envisioned a West Indian literary tradition, before focusing on the tensions between the oral folk tradition and emerging print culture. Chapter Two moves to a closer focus on the middle-class West Indians publishing the magazines and the Literary and Debating Society movement. It argues that through their magazines these clubs sought to intervene in the public sphere. Chapter Three considers the marginalised publications of three key women editors, Esther Chapman, Una Marson and Aimee Webster and identifies how the magazine form enabled these editors to pursue wider political agendas linked to their cultural aims. -

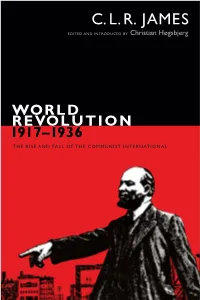

C. L. R. JAMES EDITED and INTRODUCED by Christian Høgsbjerg

C. L. R. JAMES EDITED AND INTRODUCED BY Christian Høgsbjerg WORLD REVOLUTION 1917–1936 THE RISE AND FALL OF THE COMMUNIST INTERNATIONAL WORLD REVOLUTION 1917–1936 ||||| C. L. R. James in Trafalgar Square (1935). Courtesy of Getty Images. the c. l. r. james archives recovers and reproduces for a con temporary audience the works of one of the great intel- lectual figures of the twentiethc entury, in all their rich texture, and will pres ent, over and above historical works, new and current scholarly explorations of James’s oeuvre. Robert A. Hill, Series Editor WORLD REVOLUTION 1917–1936 The Rise and Fall of the Communist International ||||| C. L. R. J A M E S Edited and Introduced by Christian Høgsbjerg duke university press Durham and London 2017 Introduction and Editor’s Note © 2017 Duke University Press World Revolution, 1917–1936 © 1937 C. L. R. James Estate Harry N. Howard, “World Revolution,” Annals of the American Acad emy of Po liti cal and Social Science, pp. xii, 429 © 1937 Pioneer Publishers E. H. Carr, “World Revolution,” International Affairs (Royal Institute of International Affairs 1931–1939) 16, no. 5 (September 1937), 819–20 © 1937 Wiley All rights reserved Printed in the United States of Amer i ca on acid- free paper ∞ Typeset in Arno Pro and Gill Sans Std by Westchester Publishing Ser vices Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Names: James, C. L. R. (Cyril Lionel Robert), 1901–1989, author. | Høgsbjerg, Christian, editor. Title: World revolution, 1917–1936 : the rise and fall of the Communist International / C. L. R. James ; edited and with an introduction by Christian Høgsbjerg. -

Download File

Projective Citizenship— The Reimagining of the Citizen in Post-War American Poetry Lytton Jackson Smith Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2012 i © 2012 Lytton Jackson Smith All rights reserved ii ABSTRACT Projective Citizenship— The Reimagining of the Citizen in Post-War American Poetry Lytton Jackson Smith This dissertation examines the work of four poets writing in a projective or “open field” tradition in post-war America: Charles Olson, Amiri Baraka/LeRoi Jones, Susan Howe, and Myung Mi Kim. It considers the way these poets engage, via innovations in poetic form, with conceptions of the citizen and meanings of citizenship at different historical moments in the United States. Drawing on recent developments in citizenship theory which have focussed on what Engin Isin calls “acts of citizenship,” “Projective Citizenship—The Reimagining of the Citizen in Post-War American Poetry” suggests that poetry might offer a means for imagining alternative notions of the citizen, conceiving of citizens as active agents rather than passive subjects. iii i Contents Acknowledgments ii Preface iii Introduction: Creative Acts of Poetry: The Bollingen Prize, the Citizen-Poet, and Projective Citizenship 1 Exiling the Transformative Poet The Bollingen Prize: Ezra Pound’s Tenuous Citizenship Creative Acts: Poets and the Claim to Citizenship Reimagining the Citizen Projective Verse—Projective Citizenship “To Try To Get Down One Citizen