Unit Iii 1. European Historiography Edward

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Socialist Minority and the Paris Commune of 1871 a Unique Episode in the History of Class Struggles

THE SOCIALIST MINORITY AND THE PARIS COMMUNE OF 1871 A UNIQUE EPISODE IN THE HISTORY OF CLASS STRUGGLES by PETER LEE THOMSON NICKEL B.A.(Honours), The University of British Columbia, 1999 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Department of History) We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA August 2001 © Peter Lee Thomson Nickel, 2001 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of Hi'sio*" y The University of British Columbia Vancouver, Canada Date AkgaS-f 30. ZOO I DE-6 (2/88) Abstract The Paris Commune of 1871 lasted only seventy-two days. Yet, hundreds of historians continue to revisit this complex event. The initial association of the 1871 Commune with the first modern socialist government in the world has fuelled enduring ideological debates. However, most historians past and present have fallen into the trap of assessing the Paris Commune by foreign ideological constructs. During the Cold War, leftist and conservative historians alike overlooked important socialist measures discussed and implemented by this first- ever predominantly working-class government. -

1964 Jaargang 19 (Xix)

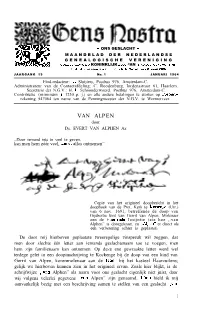

- ONS GESLACHT - MAANDBLAD DER NEDERLANDSE GENEALOGISCHE VERENIGING OOEDGEKEURD 312 KONINKLIJK BESL. “AN 16 A”O”STUS reaa. YO. 85 Llc.tstel,jk podpeKe”rd 51, KO”i”kli,k a.,,uit van J .+r,, ,833 JAARGANG 19 No. 1 JANUARI 1964 Eind-redacteur: J. Sluijters, Postbus 976, Amsterdam-C. Administrateur van de Contactafdeling: C. Roodenburg, Iordensstraat 61, Haarlem. Secretaris der N.G.V.: H. J. Schoonderwoerd, Postbus 976, Amsterdam-C. Contributie (minimum f 1230 p. j.) en alle andere betalingen te storten op Postgiro- rekening 547064 ten name van de Penningmeester der N.G.V. te Wormerveer. VAN ALPEN door Ds. EVERT VAN ALPHEN Az ,,Door iemand iets te veel te geven, kan men hem zéér veel, zoniet alles ontnemen” Copie van het origineel doopbericht in het doopboek van de Prot. Kerk te Kortenge (Utr.) van 6 nov. 1691, betreffende de doop van Gijsbertie kint van Gerrit van Alpen, Molenaer aen de Haer ende Josijntie (zie hoe ,,van Alphen” is doorgekrast, en ,,Alpen” er direct als een verbetering achter is geplaatst). De door mij hierboven geplaatste tweeregelige zinspreuk wil zeggen, dat men door slechts één letter aan iemands geslachtsnaam toe te voegen, men hem zijn familienaam kan ontnemen. Op deze ene gewraakte letter werd wel terdege gelet in een doopinschrijving te Kockenge bij de doop van een kind van Gerrit van Alpen, korenmolenaar aan de Haer bij het kasteel Haarzuilens; gelijk we hierboven kunnen zien in het origineel ervan. Zoals hier blijkt, is de schrijfwijze ,,van Alphen” als naam voor ons geslacht eigenlijk niet juist, daar wij volgens velerlei gegevens ,,van Alpen” zijn genaamd. -

Markets Not Capitalism Explores the Gap Between Radically Freed Markets and the Capitalist-Controlled Markets That Prevail Today

individualist anarchism against bosses, inequality, corporate power, and structural poverty Edited by Gary Chartier & Charles W. Johnson Individualist anarchists believe in mutual exchange, not economic privilege. They believe in freed markets, not capitalism. They defend a distinctive response to the challenges of ending global capitalism and achieving social justice: eliminate the political privileges that prop up capitalists. Massive concentrations of wealth, rigid economic hierarchies, and unsustainable modes of production are not the results of the market form, but of markets deformed and rigged by a network of state-secured controls and privileges to the business class. Markets Not Capitalism explores the gap between radically freed markets and the capitalist-controlled markets that prevail today. It explains how liberating market exchange from state capitalist privilege can abolish structural poverty, help working people take control over the conditions of their labor, and redistribute wealth and social power. Featuring discussions of socialism, capitalism, markets, ownership, labor struggle, grassroots privatization, intellectual property, health care, racism, sexism, and environmental issues, this unique collection brings together classic essays by Cleyre, and such contemporary innovators as Kevin Carson and Roderick Long. It introduces an eye-opening approach to radical social thought, rooted equally in libertarian socialism and market anarchism. “We on the left need a good shake to get us thinking, and these arguments for market anarchism do the job in lively and thoughtful fashion.” – Alexander Cockburn, editor and publisher, Counterpunch “Anarchy is not chaos; nor is it violence. This rich and provocative gathering of essays by anarchists past and present imagines society unburdened by state, markets un-warped by capitalism. -

Colonization, Education, and the Formation of Moral Character: Edward Gibbon Wakefield's a Letter from Sydney

1 Historical Studies in Education / Revue d’histoire de l’éducation ARTICLES / ARTICLES Colonization, Education, and the Formation of Moral Character: Edward Gibbon Wakefield’s A Letter from Sydney Bruce Curtis Carleton University ABSTRacT Edward Gibbon Wakefield proposed a scheme of “systematic colonization” that he claimed would guarantee the formation of civilized moral character in settler societies at the same time as it reproduced imperial class relations. The scheme, which was first hatched after Wakefield read Robert Gourlay’s A Statistical Account of Upper Canada, inverted the dominant under- standing of the relation between school and society. Wakefield claimed that without systematic colonization, universal schooling would be dangerous and demoralizing. Wakefield intervened in contemporary debate about welfare reform and population growth, opposing attempts to enforce celibacy on poor women and arguing that free enjoyment of “animal liberty” made women both moral and beautiful. RÉSUMÉ Edward Gibbon Wakefield propose que son programme de « colonisation systématique » ga- rantirait la formation de colons au caractère moral et civilisé. Ce programme, né d’une pre- mière lecture de l’oeuvre de Robert Gourlay, A Statistical Account of Upper Canada, contri- buerait à reproduire la structure des classes sociales impériales dans les colonies. Son analyse inverse la relation dominante entre école et société entretenue par la plupart de réformateurs de l’éducation. Sans une colonisation systématique, prétend Wakefield, la scolarisation universelle serait cause de danger politique et de démoralisation pour la société. Wakefield intervient dans le débat contemporain entourant les questions d’aide sociale et de croissance de la population. Il s’oppose aux efforts d’imposer le célibat au femmes pauvres et il argumente que l’expression de leur ‘liberté animale’ rend les femmes morales et belles. -

The Actuality of Critical Theory in the Netherlands, 1931-1994 By

The Actuality of Critical Theory in the Netherlands, 1931-1994 by Nicolaas Peter Barr Clingan A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Martin E. Jay, Chair Professor John F. Connelly Professor Jeroen Dewulf Professor David W. Bates Spring 2012 Abstract The Actuality of Critical Theory in the Netherlands, 1931-1994 by Nicolaas Peter Barr Clingan Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Berkeley Professor Martin E. Jay, Chair This dissertation reconstructs the intellectual and political reception of Critical Theory, as first developed in Germany by the “Frankfurt School” at the Institute of Social Research and subsequently reformulated by Jürgen Habermas, in the Netherlands from the mid to late twentieth century. Although some studies have acknowledged the role played by Critical Theory in reshaping particular academic disciplines in the Netherlands, while others have mentioned the popularity of figures such as Herbert Marcuse during the upheavals of the 1960s, this study shows how Critical Theory was appropriated more widely to challenge the technocratic directions taken by the project of vernieuwing (renewal or modernization) after World War II. During the sweeping transformations of Dutch society in the postwar period, the demands for greater democratization—of the universities, of the political parties under the system of “pillarization,” and of -

Marxism and the Solidarity Economy: Toward a New Theory of Revolution

Class, Race and Corporate Power Volume 9 Issue 1 Article 2 2021 Marxism and the Solidarity Economy: Toward a New Theory of Revolution Chris Wright [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/classracecorporatepower Part of the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Wright, Chris (2021) "Marxism and the Solidarity Economy: Toward a New Theory of Revolution," Class, Race and Corporate Power: Vol. 9 : Iss. 1 , Article 2. DOI: 10.25148/CRCP.9.1.009647 Available at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/classracecorporatepower/vol9/iss1/2 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts, Sciences & Education at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Class, Race and Corporate Power by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Marxism and the Solidarity Economy: Toward a New Theory of Revolution Abstract In the twenty-first century, it is time that Marxists updated the conception of socialist revolution they have inherited from Marx, Engels, and Lenin. Slogans about the “dictatorship of the proletariat” “smashing the capitalist state” and carrying out a social revolution from the commanding heights of a reconstituted state are completely obsolete. In this article I propose a reconceptualization that accomplishes several purposes: first, it explains the logical and empirical problems with Marx’s classical theory of revolution; second, it revises the classical theory to make it, for the first time, logically consistent with the premises of historical materialism; third, it provides a (Marxist) theoretical grounding for activism in the solidarity economy, and thus partially reconciles Marxism with anarchism; fourth, it accounts for the long-term failure of all attempts at socialist revolution so far. -

The Karl Marx

LENIN LIBRARY VO,LUME I 000'705 THE TEA~HINGS OF KARL MARX • By V. I. LENIN FLORIDA ATLANTIC UNIVERSITY U8AARY SOCIALIST - LABOR COllEClIOK INTERNATIONAL PUBLISHERS 381 FOURTH AVENUE • NEW YORK .J THE TEACHINGS OF KARL MARX BY V. I. LENIN INTERNATIONAL PUBLISHERS I NEW YORK Copyright, 1930, by INTERNATIONAL PUBLISHERS CO., INC. PRINTED IN THE U. S. A. ~72 CONTENTS KARL MARX 5 MARX'S TEACHINGS 10 Philosophic Materialism 10 Dialectics 13 Materialist Conception of History 14 Class Struggle 16 Marx's Economic Doctrine . 18 Socialism 29 Tactics of the Class Struggle of the Proletariat . 32 BIBLIOGRAPHY OF MARXISM 37 THE TEACHINGS OF KARL MARX By V. I. LENIN KARL MARX KARL MARX was born May 5, 1818, in the city of Trier, in the Rhine province of Prussia. His father was a lawyer-a Jew, who in 1824 adopted Protestantism. The family was well-to-do, cultured, bu~ not revolutionary. After graduating from the Gymnasium in Trier, Marx entered first the University at Bonn, later Berlin University, where he studied 'urisprudence, but devoted most of his time to history and philosop y. At th conclusion of his uni versity course in 1841, he submitted his doctoral dissertation on Epicure's philosophy:* Marx at that time was still an adherent of Hegel's idealism. In Berlin he belonged to the circle of "Left Hegelians" (Bruno Bauer and others) who sought to draw atheistic and revolutionary conclusions from Hegel's philosophy. After graduating from the University, Marx moved to Bonn in the expectation of becoming a professor. However, the reactionary policy of the government,-that in 1832 had deprived Ludwig Feuer bach of his chair and in 1836 again refused to allow him to teach, while in 1842 it forbade the Y0ung professor, Bruno Bauer, to give lectures at the University-forced Marx to abandon the idea of pursuing an academic career. -

A Study of Edward Gibbon and the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire

University of Wollongong Thesis Collections University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Year The historian as moralist: a study of Edward Gibbon and The decline and fall of the Roman Empire David Dillon-Smith University of Wollongong Dillon-Smith, David, The historian as moralist: a study of Edward Gibbon and The decline and fall of the Roman Empire, Doctor of Philosophy thesis, Department of History, University of Wollongong, 1982. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/1426 This paper is posted at Research Online. VOLUME TWO 312 CHAPTER SEVEN BARBARISM AND RELIGION If Gibbon's work gave classical expression to the nqtion of Rome's decline and fall, it did not close the great debate on the end of the ancient world. To some admiring contemporaries he seemed to have said the last word and he long remained without significant challenge. But eventually new questions and fresh evidence led to a diversity of answers and emphases. Perhaps only the assumption contained in his title still seems reasonably certain, though even the appropriateness of 'fall' in relation to the Western Empire has raised doubts. In discussing an aspect of the perennial question two centuries after Gibbon had gazed on the ruined greatness of the imperial city, Arnaldo Momigliano expressed satisfaction that he could at least begin with that 'piece of good news': 'it can still be considered an historical truth that the Roman Empire declined and fell'} There, however, agreement seemed to end and even when attention is confined to Gibbon's own contribution to the debate, there is divergence of opinion as to what constitutes the theme and crux of his version of Rome's decline and fall. -

Understanding the Reasons Behind the Failure of Wakefield's Systematic Colonization in South

When Colonization Goes South: Understanding the Reasons Behind the Failure of Wakefield’s Systematic Colonization in South Australia Edwyna Harris Monash University Sumner La Croix* University of Hawai‘i 3 December 2018 Abstract Britain after the Napoleonic wars saw the rise of colonial reformers, such as Edward Wakefield, who had extensive influence on British colonial policy. A version of Wakefield’s “System of Colonization” became the basis for an 1834 Act of Parliament establishing the South Australia colony. We use extended versions of Robert Lucas’s 1990 model of a colonial economy to illustrate how Wakefield’s institutions were designed to work. Actual practice followed some of Wakefield’s principles to the letter, with revenues from SA land sales used to subsidize passage for more than 15,000 emigrants over the 1836-1840 period. Other principles, such as surveying land in advance of settlement and maintaining a sufficient price of land, were ignored. Initial problems stemming from delays in surveying and a dysfunctional division of executive authority slowed the economy’s development over its first three years and led to a financial crisis. These difficulties aside, we show that actual SA land institutions were more aligned with geographic and political conditions in SA than the ideal Wakefield institutions and that the SA colony thrived after it took measures to speed surveying and reform its system of divided executive authority. Please do not quote or cite or distribute without permission © For Presentation at the ASSA Meetings, Atlanta, Georgia January 4, 8-10 am, Atlanta Marriott Marquis, L505 Key words: Adelaide; colonization; priority land order; South Australia; auction; Wakefield; special surveys; land concentration; emigration JEL codes: N47, N57, N97, R30, D44 *Edwyna Harris, Dept. -

The Libraries of the Boswells of Auchinleck, 1695–1825

chapter 4 Affleck Generations: The Libraries of the Boswells of Auchinleck, 1695–1825 James J. Caudle* As the ends of such a partnership cannot be obtained in many genera- tions, it becomes a partnership not only between those who are living, but between those who are living, those who are dead, and those who are to be born.1 edmund burke ... I consider a public sale as the most laudable method of disposing of it. From such sales my books were chiefly collected, and when I can no lon- ger use them they will be again culled by various buyers according to the measure of their wants and means … [I do not intend] to bury my trea- sure in a country mansion under the key of a jealous master! I am not flattered by the [idea which you propose of the] Gibbonian collection.2 edward gibbon ∵ These two quotations from two acquaintances of James Boswell (1740–95) sug- gest an essential tension in eighteenth-century private libraries, between the * This work emerged from over five years of collaboration with Terry Seymour, as well as J erry Morris and his team, on identifying Boswell’s books. Much of the work on this chapter was done while on a Fleeman Fellowship at the University of St Andrews in spring 2016. There, I benefitted from discussions with David Allan and Tom Jones, and the comments by the Eng- lish Research Seminar Series to whom I presented a version of this chapter. 1 The Beauties of the Late Right Hon. Edmund Burke … In Two Volumes (London: printed by J.W. -

Writings on the American Civil War Karl Marx and Frederick Engels Writings on the North American Civil War

Writings on the American Civil War Karl Marx and Frederick Engels Writings on the North American Civil War Karl Marx: The North American Civil War October, 1861 The Trent Case November, 1861 The Anglo-American Conflict November, 1861 Controversy Over the Trent Case December, 1861 The Progress of Feelings in England December, 1861 The Crisis Over the Slavery Issue December, 1861 News from America December, 1861 The Civil War in the United States October, 1861 The Dismissal of Frémont November, 1861 http://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1860/uscivwar/index.htm (1 of 2) [23/08/2000 17:11:09] Writings on the American Civil War Friedrich Engels: Lessons of the American Civil War December, 1861 Marx/Engels Works Archive http://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1860/uscivwar/index.htm (2 of 2) [23/08/2000 17:11:09] http://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1860/uscivwar/index-lg.jpg http://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1860/uscivwar/index-lg.jpg [23/08/2000 17:11:31] The North American Civil War Karl Marx The North American Civil War Written: October 1861 Source: Marx/Engels Collected Works, Volume 19 Publisher: Progress Publishers, Moscow, 1964 First Published: Die Presse No. 293, October 25, 1861 Online Version: marxists.org 1999 Transcribed: Bob Schwarz HTML Markup: Tim Delaney in 1999. London, October 20, 1861 For months the leading weekly and daily papers of the London press have been reiterating the same litany on the American Civil War. While they insult the free states of the North, they anxiously defend themselves against the suspicion of sympathising with the slave states of the South. -

The Political Nature of the Paris Commune of 1871 and Manifestations of Marxist Ideology in the Official Publications of the Central Committee

Virginia Commonwealth University VCU Scholars Compass Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2018 The Political Nature of the Paris Commune of 1871 and Manifestations of Marxist Ideology in the Official Publications of the Central Committee Emily M. Jones Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd Part of the European History Commons, Intellectual History Commons, Labor History Commons, Political History Commons, and the Social History Commons © The Author Downloaded from https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd/5417 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at VCU Scholars Compass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of VCU Scholars Compass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Political Nature of the Paris Commune of 1871 and Manifestations of Marxist Ideology in the Official Publications of the Central Committee A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts at Virginia Commonwealth University by Emily Marshall Jones Bachelor of Arts, Randolph-Macon College, 2010 Director: Joseph W. Bendersky, PhD Department of History Virginia Commonwealth University Richmond, Virginia May, 2018 ii Acknowledgements I would like to thank Dr. Joseph Bendersky for his guidance and encouragement. His direction and excellent advising made both my research and this written work possible. I would also like to thank my readers, Dr. John Herman and Dr. Robert Godwin-Jones for their efforts, advice, and input. I want to thank my parents for their love, support, enthusiasm, and, most of all, their faith in me.