Projects and Peasants: Russia's Eighteenth Century 5

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Samuel Johnson's Childhood Illnesses and the King's Evil

SAMUEL JOHNSON'S CHILDHOOD ILLNESSES AND THE KING'S EVIL by LAWRENCE C. McHENRY, JR. AND RONALD MAC KEITH 'HERE is a brave boy,' proclaimed George Hector,* when he brought Samuel Johnson into the world. From this moment and throughout most of his childhood, young Sam was harassed by a variety of afflictions that troubled his daily existence, but did not prevent him from eventually becoming one of England's outstanding literary figures. Samuel Johnson's adult illnesses and the history of his childhood have been described by many writers, but no separate work is available on his childhood medical history. The purpose ofthis paper is to describe Johnson's childhood medical disorders and their consequences. The principal source of information on this period in Johnson's life is from an autobiographical sketch, An account of the life of Dr. Samuel Johnson from his birth to his eleventh year, written by himself. Johnson apparently called this his 'Annals' and his two principal biographers, Boswell and Hawkins, did not know of its existence. This was written when he was 55 years old and was 'among the mass of papers which were ordered to be committed to the flames a few days before his death.'** Johnson's 'Annals' gives a record of his early affections, but it contains a rather questionable medical implication that has been perpetuated as fact. This is that Johnson developed tuberculosis during the first few weeks of his life. We propose to point out that this is unlikely and to show that it is much more probable that he developed tuberculosis later, when he was about two years old. -

The Inextricable Link Between Literature and Music in 19Th

COMPOSERS AS STORYTELLERS: THE INEXTRICABLE LINK BETWEEN LITERATURE AND MUSIC IN 19TH CENTURY RUSSIA A Thesis Presented to The Graduate Faculty of The University of Akron In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Music Ashley Shank December 2010 COMPOSERS AS STORYTELLERS: THE INEXTRICABLE LINK BETWEEN LITERATURE AND MUSIC IN 19TH CENTURY RUSSIA Ashley Shank Thesis Approved: Accepted: _______________________________ _______________________________ Advisor Interim Dean of the College Dr. Brooks Toliver Dr. Dudley Turner _______________________________ _______________________________ Faculty Reader Dean of the Graduate School Mr. George Pope Dr. George R. Newkome _______________________________ _______________________________ School Director Date Dr. William Guegold ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page CHAPTER I. OVERVIEW OF THE DEVELOPMENT OF SECULAR ART MUSIC IN RUSSIA……..………………………………………………..……………….1 Introduction……………………..…………………………………………………1 The Introduction of Secular High Art………………………………………..……3 Nicholas I and the Rise of the Noble Dilettantes…………………..………….....10 The Rise of the Russian School and Musical Professionalism……..……………19 Nationalism…………………………..………………………………………..…23 Arts Policies and Censorship………………………..…………………………...25 II. MUSIC AND LITERATURE AS A CULTURAL DUET………………..…32 Cross-Pollination……………………………………………………………...…32 The Russian Soul in Literature and Music………………..……………………...38 Music in Poetry: Sound and Form…………………………..……………...……44 III. STORIES IN MUSIC…………………………………………………… ….51 iii Opera……………………………………………………………………………..57 -

Democracy’ in Somerset and Beyond

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-89755-6 - Romanticism, Revolution and Language: The Fate of the Word from Samuel Johnson to George Eliot John Beer Excerpt More information chapter 1 ‘Democracy’ in Somerset and beyond The political impact of the French Revolution in England was strangely oblique, even when one remembers that it was largely being experienced at one remove. My concern here is not only with some examples of that oblique reaction but with language generally, and with the manner in which the growing questioning of authority during the period reflected a more profound alteration, taking place over a much longer period – a movement from what might be termed the language of fidelity to the cultivation of dialects that could be regarded as more critically oriented. To put the matter another way, whereas in medieval times writers had been so close to the religion of their surrounding culture that they did not need to think about the possible religious implications of their language, by the middle of the twentieth century, they would have become so self-conscious and self-critical that they could not write anything containing such implications and not be aware of possible commenting voices ranging from the harshly critical to the warmly favourable. The 1790s, I shall maintain, provided a crucial juncture for this development. In addition, however, attention may be drawn to recent emphases in the writing of history by which the possibility of concentrating on a small and particular detail and expanding one’s attention from there can be explored, or, alternately, one may begin by proceeding to the widest possible extreme and moving inward. -

On the Question of the Main Concepts and Theories of the Origin of the State

Law/1. Theory of State and Law Zhadan V. N. PhD in Law, Associate Professor Kazan Federal University, Elabuga Institute, Russia ON THE QUESTION OF THE MAIN CONCEPTS AND THEORIES OF THE ORIGIN OF THE STATE Abstract. The article is devoted to the discussion of the main concepts and theories of the origin of the state based on the analysis of General theoretical provisions of legal science, scientific approaches and author's understanding. Key words: question, basic, concept, theory, origin, state, analysis, General theoretical provisions, approaches. In the science of state and law (and especially the theory of state and law), there are many scientific materials that consider the laws of the origin, development and functioning of the state and law, historical types, forms, functions and other aspects that characterize the state and law [1-2]. Many scientists specializing in the theory of state and law (and in other areas of scientific research) offer their views on the theoretical characteristics of the state and law, their features, state-political forms and functions, and many other aspects, which does not deprive the author to Express his opinion on some issues related to the discussion of the origin of the state. The subject of this review will be questions about the main concepts and theories of the origin of the state. Based on the research subject of interest the following questions: what is a theory of the origin of the state; what the right science is called basic theory of the origin of the state; what are the terms "concept" and "theory"; which is accepted to highlight the concepts and theories of the origin of the state; how key concepts and theories explain the emergence of the state? The author shares the scientific approach that the study of theories of the origin of the state (and law) is not only cognitive (theoretical), but also political and practical in nature [3, p. -

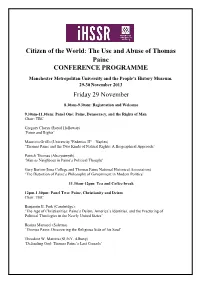

The Use and Abuse of Thomas Paine CONFERENCE PROGRAMME

Citizen of the World: The Use and Abuse of Thomas Paine CONFERENCE PROGRAMME Manchester Metropolitan University and the People’s History Museum, 29-30 November 2013 Friday 29 November 8.30am-9.30am: Registration and Welcome 9.30am-11.30am: Panel One: Paine, Democracy, and the Rights of Man Chair: TBC Gregory Claeys (Royal Holloway) ‘Paine and Rights’ Maurizio Griffo (University "Federico II" – Naples) ‘Thomas Paine and the Two Kinds of Natural Rights: A Biographical Approach’ Patrick Thomas (Aberystwyth) ‘Man as Neighbour in Paine’s Political Thought’ Gary Berton (Iona College and Thomas Paine National Historical Association) ‘The Distortion of Paine’s Philosophy of Government in Modern Politics’ 11.30am-12pm: Tea and Coffee break 12pm-1.30pm: Panel Two: Paine, Christianity and Deism Chair: TBC Benjamin E. Park (Cambridge): ‘The Age of Christianities: Paine’s Deism, America’s Identities, and the Fracturing of Political Theologies in the Newly United States’ Rosina Martucci (Salerno) ‘Thomas Paine: Discovering the Religious Side of his Soul’ Theodore W. Marotta (SUNY, Albany) ‘Defending God: Thomas Paine’s Last Crusade’ 1.30-2.30pm: Lunch 2.30pm-4pm: Panel Three: The Image and Idea of Paine in a Transatlantic Context Chair: Catherine Armstrong (MMU) Matteo Battistini (Bologna) Atlantic Fragments of Thomas Paine: Democratic Language and its Class Meaning in Paine’s Early Nineteenth Century Legacy on both the English and American Shores of the Ocean. Sam Edwards (MMU) ‘He Came From America Didn’t He? Identity, Nationality and the 1964 Thetford -

DOES the JEWISH PAST HAVE a FUTURE? by Sholome Michael Gelber 251

CONTENTS EDITORS' PREFACE Ν THE HISTORIC QUEST BY JOSEPH L. BLAU VII BIBLIOGRAPHY OF THE WRITINGS OF SALO WITTMAYER BARON XV THE CORRESPONDENCE OF TOBIAS BEN MOSES, THE KARAITE, OF CON- STANTINOPLE BY ZVI ANKORI 1 TOWARD THE DAWN OF HISTORY BY MEIR BEN-HORIN 39 THE MESSIANIC SELF-CONSCIOUSNESS OF ABRAHAM ABULAFIA: A TEN- TATIVE EVALUATION BY ABRAHAM BERGER 55 THE CLOAKMAKERS' STRIKE OF 1910 BY HYMAN BERMAN 63 TRADITION AND INNOVATION BY JOSEPH L. BLAU 95 FELIX LIBERTATE AND THE EMANCIPATION OF DUTCH JEWRY BY HERBERT I. BLOOM 105 AMERICAN JEWRY-REFLECTIONS ON SOCIAL, COMMUNAL, AND SPIRITUAL TRENDS BY SAMUEL M. BLUMENFIELD 123 MORALITY AND RELIGION IN THE THEOLOGY OF MAIMONIDES BY BEN Ζ ION BOKSER 139 AN AMERICAN JEW AT THE PARIS PEACE CONFERENCE OF 1919: EXCERPTS FROM THE DIARY OF OSCAR S. STRAUS BY NAOMI W. COHEN 159 THE LAFAYETTE COMMITTEE FOR JEWISH EMANCIPATION BY ABRAHAM G. DUKER 169 THE BACKGROUND OF THE BERLIN HASKALAH BY ISAAC EISENSTEIN- BARZILAY 183 ASPECTS OF THE JEWISH COMMUNAL CRISIS IN THE PERIOD OF THE NAZI REGIME IN GERMANY, AUSTRIA, AND CZECHOSLOVAKIA BY PHILIP FRIEDMAN 199 JEWISH IMMIGRANTS IN LONDON IN THE 1880's by Lloyd P. Gartner 231 XIV CONTENTS DOES THE JEWISH PAST HAVE A FUTURE? by Sholome Michael Gelber 251 AN AMERICAN ANTI-SEMITE IN THE NINETEENTH CENTURY BY LEONARD A. GREENBERG AND HAROLD J. JONAS 265 FLIGHT FROM THE SLUMS BY HYMAN B. GRINSTEIN 285 WELLHAUSEN'S INTERPRETATION OF ISRAEL'S RELIGIOUS HISTORY: A REAPPRAISAL OF HIS RULING IDEAS BY HERBERT F. HAHN 299 THE CONSERVATIVE RABBINATE: A SOCIOLOGICAL STUDY BY ARTHUR HERTZBERG 309 THE JEWISH ASSOCIATION IN AMERICA BY ISAAC LEVITATS 333 ON MARRIAGE IN ALALAKH BY ISAAC MENDELSOHN 351 DOCTOR SAMUEL JOHNSON'S GRAMMAR AND HEBREW PSALTER BY ISIDORE S. -

The Times and Influence of Samuel Johnson

UNIVERZITA PALACKÉHO V OLOMOUCI FILOZOFICKÁ FAKULTA Katedra anglistiky a amerikanistiky Martina Tesařová The Times and Influence of Samuel Johnson Bakalářská práce Studijní obor: Anglická filologie Vedoucí práce: Mgr. Ema Jelínková, Ph.D. OLOMOUC 2013 Prohlášení Prohlašuji, že jsem bakalářskou práci na téma „Doba a vliv Samuela Johnsona“ vypracovala samostatně a uvedla úplný seznam použité a citované literatury. V Olomouci dne 15.srpna 2013 …………………………………….. podpis Poděkování Ráda bych poděkovala Mgr. Emě Jelínkové, Ph.D. za její stále přítomný humor, velkou trpělivost, vstřícnost, cenné rady, zapůjčenou literaturu a ochotu vždy pomoci. Rovněž děkuji svému manželovi, Joe Shermanovi, za podporu a jazykovou korekturu. Johnson, to be sure, has a roughness in his manner, but no man alive has a more tender heart. —James Boswell Table of Contents 1. Introduction ..................................................................................................... 1 2. The Age of Johnson: A Time of Reason and Good Manners ......................... 3 3. Samuel Johnson Himself ................................................................................. 5 3.1. Life and Health ......................................................................................... 5 3.2. Works ..................................................................................................... 10 3.3. Johnson’s Club ....................................................................................... 18 3.4. Opinions and Practice ............................................................................ -

Methodological Basis of Legal Personality of the State (Civil Aspects)

Journal of Legal, Ethical and Regulatory Issues Volume 20, Special Issue 1, 2017 METHODOLOGICAL BASIS OF LEGAL PERSONALITY OF THE STATE (CIVIL ASPECTS) Anatoliy V Kostruba, Vasyl Stefanyk Precarpathian National University ABSTRACT Article deals with the investigation the legal nature of the state. It was found that the state is the allied unity of settled people provided with primary power of primacy. The essence of the state lies in creation of conditions for the development of the civil society, implementation of shared interests of members of society. The state is a means of social compromise of members of civil society. It appears not only as a form of provision of such social compromise, but also as an active and equal member of the relevant legal relations. The ability of the state to be an active participant in social communications configures its natural right that can and should be implemented. As a result, the subject gets legal opportunities for its activities and transformed into a legal person the nature of which is revealed through the signs of interest, will of the subject and its individual separation. Since the state is a union of interests of persons united in the unified social organism for their support, the fact that the legal entity as a legal person synthesizes in itself not only characteristics peculiar to the corporation, but also characteristics peculiar to the state as a legal person is justified. Implementation of the civil capacity of the state is revealed through the institution of representation. The justification of universal character of legal capacity of the state is given. -

Samuel Johnson's Pragmatism and Imagination

Samuel Johnson’s Pragmatism and Imagination Samuel Johnson’s Pragmatism and Imagination By Stefka Ritchie Samuel Johnson’s Pragmatism and Imagination By Stefka Ritchie This book first published 2018 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2018 by Stefka Ritchie All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-1603-2 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-1603-8 A sketch of Samuel Johnson, after Joshua Reynold (circa 1769) By Svetlan Stefanov (2009) (http://www.phot4oart.com) CONTENTS List of Illustrations ................................................................................... viii Abstract ...................................................................................................... ix Preface ........................................................................................................ xi Acknowledgements .................................................................................. xiv Chronology: Samuel Johnson (1709-1784) ............................................... xv Abbreviations ......................................................................................... xviii Chapter One ................................................................................................ -

Monarchs and the Enlightenment in Russia and Central Europe | University College London

09/26/21 SEHI3009: Monarchs and the Enlightenment in Russia and Central Europe | University College London SEHI3009: Monarchs and the View Online Enlightenment in Russia and Central Europe Alexander, John T., Bubonic Plague in Early Modern Russia: Public Health and Urban Disaster (Oxford University Press 2003) Augustine WR, ‘Notes toward a Portrait of the Eighteenth-Century Russian Nobility’ [1970] Canadian Slavic studies: a quarterly journal devoted to Russia and East Europe = Revue canadienne d’études slaves Balázs, Éva H., Hungary and the Habsburgs, 1765-1800: An Experiment in Enlightened Absolutism (Central European University Press 1997) Bartlett, Roger P., Human Capital: The Settlement of Foreigners in Russia, 1762-1804 (Cambridge University Press 1979) Bartlett RP, ‘The Question of Serfdom: Catherine II, the Russian Debate and the View from the Baltic Periphery (J. G. Eisen and G. H. Merkel)’, Russia in the age of the enlightenment: essays for Isabel de Madariaga, vol Studies in Russia and East Europe (Macmillan in association with the School of Slavonic and East European Studies, University of London 1990) Bartlett RP, ‘Defences of Serfdom in Eighteenth Century Russia’, A window on Russia: papers from the V International Conference of the Study Group on Eighteenth-Century Russia, Gargnano, 1994 (La Fenice Edizioni 1996) Bartlett RP, ‘Russia’s First Abolitionist: The Political Philosophy Og J. G. Eisen’ Jahrbücher für Geschichte Osteuropas Beales D, ‘Religion and Culture’, The eighteenth century: Europe, 1688-1815, vol The short -

Pope and Slavery

Proceedings of the British Academy, 91,27753 Pope and Slavery HOWARD ERSKINE-HILL I am certainly desirous to run from my Country, if you’ll run from yours, and study Popery and Slavery abroad a while, to reconcile ourselves to the Church & State we may find at home on our return. (Pope to the Earl of Marchmont, 22 June 1740 Correspondence, IV. 250) 1 IN 1790 THE POET Alexander Radishchev, called ‘The First Russian Radical’, printed his Journey from St. Petersburg to Moscow, criticising the condition of the serfs under Catherine the Great, and dedicating it without permission to his friend, the poet A. M. Kutuzov. Kutuzov, alarmed with reason at this dedication, recounts how on an earlier occasion he had remonstrated with Radishchev, quoting to him in English Pope’s translation of Homer’s lfiad,Bk. I, the lines of Calchas to Achilles on the perils of telling unwelcome truths to kings: For I must speak what Wisdom would conceal, And Truths invidious [to] the Great reveal. Bold is the task! when Subjects grown too wise Instruct a Monarch where his Error lies; For tho’ we deem the short-liv’d fury past Be sure, the Mighty will revenge at last. (I. 101-6)’ 0 The British Academy 1998. ‘In my reference to Radishchev I am indebted to Professor Monica Partridge and to Professor A. G. Cross. The lines quoted from Pope’s Iliad translation by A. M. Kutuzov are I. 101-6; T. E. VIII. 92. The allusion is briefly discussed in David Marshal Lang, The First Russian Radical 1749-1802 (London, 1959), pp. -

Samuel Johnson (1709-84)

Samuel Johnson (1709-84) gsdfgsd Dr. Samuel Johnson • From his biography in the Norton 2841-2843: • Crowning achievement: his English Dictionary. • Famous style: ―The great generalist‖ • direct, memorable, and sometimes harsh (little patience for elaborate nonsense). • A famous talker, known for his conversation. • The subject of the most famous biography in English literature—Boswell’s Life of Johnson. 1729: Left Oxford—too poor. 1737-55: Tutoring and ―hack writing‖ in London for money. 1747-55: A Dictionary of the English Language (assisted). 1750-52: The Rambler (bi- weekly published essays). 1759: Rasselas (moral tales, written in one week). 1762: ―The Club‖—by now, an influential celebrity among artists, writers, intellectuals. 1763: Met Boswell (22), who recorded Johnson’s life. 1779-81: Lives of the Poets. Johnson wrote fast and worked hard. 18th C Writers’ Relations to the Reading Public • Back in the Renaissance, books were the property of the few; books were expensive, and their production (the author’s time and the costs to publish them) was often supported by a patron. • In the 18th C, there was a shift from the patron to the public. • Books became much cheaper to produce, and an expanding middle class would buy them. • Pope may have looked down on new reading public, but the new market of readers freed writers from the old model of patronage. • Reading brief works on contemporary arts & issues flourished. Periodicals emerged—not unlike like today’s weekly or monthly magazines. Today we have magazines like The New Yorker. • In the 18th C, instead of The New Yorker, there was The Spectator, The Idler, and The Rambler.