Guo Gu (Professor Jimmy Yu) Is a Worthy Heir to the Great Chan Master Sheng Yen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tianjin Travel Guide

Tianjin Travel Guide Travel in Tianjin Tianjin (tiān jīn 天津), referred to as "Jin (jīn 津)" for short, is one of the four municipalities directly under the Central Government of China. It is 130 kilometers southeast of Beijing (běi jīng 北京), serving as Beijing's gateway to the Bohai Sea (bó hǎi 渤海). It covers an area of 11,300 square kilometers and there are 13 districts and five counties under its jurisdiction. The total population is 9.52 million. People from urban Tianjin speak Tianjin dialect, which comes under the mandarin subdivision of spoken Chinese. Not only is Tianjin an international harbor and economic center in the north of China, but it is also well-known for its profound historical and cultural heritage. History People started to settle in Tianjin in the Song Dynasty (sòng dài 宋代). By the 15th century it had become a garrison town enclosed by walls. It became a city centered on trade with docks and land transportation and important coastal defenses during the Ming (míng dài 明代) and Qing (qīng dài 清代) dynasties. After the end of the Second Opium War in 1860, Tianjin became a trading port and nine countries, one after the other, established concessions in the city. Historical changes in past 600 years have made Tianjin an unique city with a mixture of ancient and modem in both Chinese and Western styles. After China implemented its reforms and open policies, Tianjin became one of the first coastal cities to open to the outside world. Since then it has developed rapidly and become a bright pearl by the Bohai Sea. -

Kūnqǔ in Practice: a Case Study

KŪNQǓ IN PRACTICE: A CASE STUDY A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN THEATRE OCTOBER 2019 By Ju-Hua Wei Dissertation Committee: Elizabeth A. Wichmann-Walczak, Chairperson Lurana Donnels O’Malley Kirstin A. Pauka Cathryn H. Clayton Shana J. Brown Keywords: kunqu, kunju, opera, performance, text, music, creation, practice, Wei Liangfu © 2019, Ju-Hua Wei ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to express my gratitude to the individuals who helped me in completion of my dissertation and on my journey of exploring the world of theatre and music: Shén Fúqìng 沈福庆 (1933-2013), for being a thoughtful teacher and a father figure. He taught me the spirit of jīngjù and demonstrated the ultimate fine art of jīngjù music and singing. He was an inspiration to all of us who learned from him. And to his spouse, Zhāng Qìnglán 张庆兰, for her motherly love during my jīngjù research in Nánjīng 南京. Sūn Jiàn’ān 孙建安, for being a great mentor to me, bringing me along on all occasions, introducing me to the production team which initiated the project for my dissertation, attending the kūnqǔ performances in which he was involved, meeting his kūnqǔ expert friends, listening to his music lessons, and more; anything which he thought might benefit my understanding of all aspects of kūnqǔ. I am grateful for all his support and his profound knowledge of kūnqǔ music composition. Wichmann-Walczak, Elizabeth, for her years of endeavor producing jīngjù productions in the US. -

Just This Is It: Dongshan and the Practice of Suchness / Taigen Dan Leighton

“What a delight to have this thorough, wise, and deep work on the teaching of Zen Master Dongshan from the pen of Taigen Dan Leighton! As always, he relates his discussion of traditional Zen materials to contemporary social, ecological, and political issues, bringing up, among many others, Jack London, Lewis Carroll, echinoderms, and, of course, his beloved Bob Dylan. This is a must-have book for all serious students of Zen. It is an education in itself.” —Norman Fischer, author of Training in Compassion: Zen Teachings on the Practice of Lojong “A masterful exposition of the life and teachings of Chinese Chan master Dongshan, the ninth century founder of the Caodong school, later transmitted by Dōgen to Japan as the Sōtō sect. Leighton carefully examines in ways that are true to the traditional sources yet have a distinctively contemporary flavor a variety of material attributed to Dongshan. Leighton is masterful in weaving together specific approaches evoked through stories about and sayings by Dongshan to create a powerful and inspiring religious vision that is useful for students and researchers as well as practitioners of Zen. Through his thoughtful reflections, Leighton brings to light the panoramic approach to kōans characteristic of this lineage, including the works of Dōgen. This book also serves as a significant contribution to Dōgen studies, brilliantly explicating his views throughout.” —Steven Heine, author of Did Dōgen Go to China? What He Wrote and When He Wrote It “In his wonderful new book, Just This Is It, Buddhist scholar and teacher Taigen Dan Leighton launches a fresh inquiry into the Zen teachings of Dongshan, drawing new relevance from these ancient tales. -

The Koan : Texts and Contexts in Zen Buddhism

1 The Form and function of Koan Literature A Historical Overview T. GRIFFITH FOULK ANY DISCUSSION o f koan s i n th e histor y o f Eas t Asia n Buddhis m needs t o star t wit h a definitio n o f the wor d "koan " itself , fo r althoug h th e word ha s entere d int o relativel y commo n Englis h usage , fe w people hav e a clear idea o f what it refers to, and ambiguities remain even in scholarly stud- ies.1 The first part o f this chapter, accordingly , is dedicated t o a brief history of the koan, with particular attentio n t o th e etymology of the word and th e evolution of its meaning in China an d Japan. Th e second part delineates the range of texts that I take to be "koan literature " an d explains my reasons for regarding the m as such. The remaining part s of the chapter are dedicated to a form-critical analysi s of the comple x internal structur e o f the koan literatur e and an exploration o f how that literatur e has both mirrored an d serve d as a model for its social and ritual functions. The treatmen t o f the koa n a s a literar y genre in thi s chapter ma y strik e some readers as peculiar or even irrelevant. After all , many accounts of koans today, both popular an d scholarly, describe them as devices that ar e meant to focus th e mind in meditation, t o confound the discursive intellect, freezing it into a single ball of doubt, an d finally to trigger an awakening (J. -

Abstracts (PDF)

Abstracts of the Psychonomic Society — Volume 7 — November 2002 43rd Annual Meeting — November 21–24, 2002 — Kansas City, Missouri Posters 1–7 Thursday Evening Papers and Posters Presented at the 43rd Annual Meeting of the Psychonomic Society Hyatt and Westin Hotels, Kansas City, Missouri November 21–24, 2002 POSTER SESSION I tection was improved, but stimulus identification did not show a com- Crown Hall, Thursday Evening, 6:00–7:30 parable improvement. These results suggest that other stimulus infor- mation, such as luminance, is capable of influencing detection per- •VISUAL PERCEPTION • formance but may not improve identification. (1) (4) Priming and Perception of Androgynous Faces: What You See Is Prerecognition Visual Processing of Words, Pseudowords, and Not What You Get. JAY FRIEDENBERG, SARIT KANIEVSKY, & Nonwords. BART A. VANVOORHIS, University of Wisconsin, La MEGAN KWASNIAK, Manhattan College—Fifty-six participants Crosse, & LLOYD L. AVANT, Iowa State University—Viewers made judged the perceived sex and attractiveness of male, female, and morph duration or brightness judgments for pre- and postmasked 15-msec in- faces. The morphs were 50:50 composite blends of single male and puts of words, pseudowords, and nonwords when the words were high- female faces. In the no-prime control, only morphs were presented. image nouns, abstract nouns, and verbs and when the pseudowords Each morph was preceded by its male face in the male-prime condition, and nonwords were derived from letters of the same word or across and by its female face in the female-prime condition. The results showed the three word types. Results showed that for both brightness and du- a reverse priming effect. -

Gateless Gate Has Become Common in English, Some Have Criticized This Translation As Unfaithful to the Original

Wú Mén Guān The Barrier That Has No Gate Original Collection in Chinese by Chán Master Wúmén Huìkāi (1183-1260) Questions and Additional Comments by Sŏn Master Sǔngan Compiled and Edited by Paul Dōch’ŏng Lynch, JDPSN Page ii Frontspiece “Wú Mén Guān” Facsimile of the Original Cover Page iii Page iv Wú Mén Guān The Barrier That Has No Gate Chán Master Wúmén Huìkāi (1183-1260) Questions and Additional Comments by Sŏn Master Sǔngan Compiled and Edited by Paul Dōch’ŏng Lynch, JDPSN Sixth Edition Before Thought Publications Huntington Beach, CA 2010 Page v BEFORE THOUGHT PUBLICATIONS HUNTINGTON BEACH, CA 92648 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. COPYRIGHT © 2010 ENGLISH VERSION BY PAUL LYNCH, JDPSN NO PART OF THIS BOOK MAY BE REPRODUCED OR TRANSMITTED IN ANY FORM OR BY ANY MEANS, GRAPHIC, ELECTRONIC, OR MECHANICAL, INCLUDING PHOTOCOPYING, RECORDING, TAPING OR BY ANY INFORMATION STORAGE OR RETRIEVAL SYSTEM, WITHOUT THE PERMISSION IN WRITING FROM THE PUBLISHER. PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA BY LULU INCORPORATION, MORRISVILLE, NC, USA COVER PRINTED ON LAMINATED 100# ULTRA GLOSS COVER STOCK, DIGITAL COLOR SILK - C2S, 90 BRIGHT BOOK CONTENT PRINTED ON 24/60# CREAM TEXT, 90 GSM PAPER, USING 12 PT. GARAMOND FONT Page vi Dedication What are we in this cosmos? This ineffable question has haunted us since Buddha sat under the Bodhi Tree. I would like to gracefully thank the author, Chán Master Wúmén, for his grace and kindness by leaving us these wonderful teachings. I would also like to thank Chán Master Dàhuì for his ineptness in destroying all copies of this book; thankfully, Master Dàhuì missed a few so that now we can explore the teachings of his teacher. -

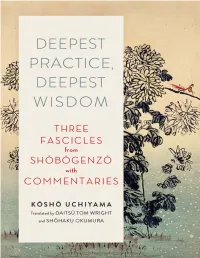

Deepest Practice, Deepest Wisdom

“A magnificent gift for anyone interested in the deep, clear waters of Zen—its great foundational master coupled with one of its finest modern voices.” —JISHO WARNER, former president of the Soto Zen Buddhist Association FAMOUSLY INSIGHTFUL AND FAMOUSLY COMPLEX, Eihei Dōgen’s writings have been studied and puzzled over for hundreds of years. In Deepest Practice, Deepest Wisdom, Kshō Uchiyama, beloved twentieth-century Zen teacher, addresses himself head-on to unpacking Dōgen’s wisdom from three fascicles (or chapters) of his monumental Shōbōgenzō for a modern audience. The fascicles presented here from Shōbōgenzō, or Treasury of the True Dharma Eye, include “Shoaku Makusa” or “Refraining from Evil,” “Maka Hannya Haramitsu” or “Practicing Deepest Wisdom,” and “Uji” or “Living Time.” Daitsū Tom Wright and Shōhaku Okumura lovingly translate Dōgen’s penetrating words and Uchiyama’s thoughtful commentary on each piece. At turns poetic and funny, always insightful, this is Zen wisdom for the ages. KŌSHŌ UCHIYAMA was a preeminent Japanese Zen master instrumental in bringing Zen to America. The author of over twenty books, including Opening the Hand of Thought and The Zen Teaching of Homeless Kodo, he died in 1998. Contents Introduction by Tom Wright Part I. Practicing Deepest Wisdom 1. Maka Hannya Haramitsu 2. Commentary on “Maka Hannya Haramitsu” Part II. Refraining from Evil 3. Shoaku Makusa 4. Commentary on “Shoaku Makusa” Part III. Living Time 5. Uji 6. Commentary on “Uji” Part IV. Comments by the Translators 7. Connecting “Maka Hannya Haramitsu” to the Pāli Canon by Shōhaku Okumura 8. Looking into Good and Evil in “Shoaku Makusa” by Daitsū Tom Wright 9. -

釋智譽 Phra Kiattisak Ponampon (Kittipanyo Bhikkhu)

MISSION, MEDITATION AND MIRACLES: AN SHIGAO IN CHINESE TRADITION 釋智譽 PHRA KIATTISAK PONAMPON (KITTIPANYO BHIKKHU) THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN RELIGIOUS STUDIES, UNIVERSITY OF OTAGO, DUNEDIN, NEW ZEALAND OCTOBER 2014 ii ABSTRACT An Shigao is well known for the important role he played in the early transmission of Buddhism into China, and Chinese Buddhists have considered him to be a meditation master for centuries. However, recent scholarship on An Shigao (Zürcher, 2007; Forte, 1995; Zacchetti, 2002; Nattier, 2008) has focused on his role as a precursor of the Mahāyāna, his ordination status, and the authenticity of the texts attributed to him rather than the meditation techniques he used and taught to his followers in China. One reason for this is because his biographies are full of supernatural details, and many of the texts attributed to An Shigao are pseudepigraphia. In the first part of this MA thesis, I explore the biographical traditions about An Shigao. The close reading of the oldest biographies of An Shigao shows that during the time he was active in China, An Shigao was respected as a missionary, a meditation master and a miracle worker as well as a translator. This reputation continued to be important for Chinese Buddhists long after his death. Despite his reputation, his biographies contain almost no information about the form of meditation that he practiced and taught. However they contain much information about his supernatural abilities. In the second part of this MA thesis, I make a statistical analysis of all the meditation sūtras attributed to An Shigao and his school. -

On the Endeavor of the Way Bendō-Wa

1. On the Endeavor of the Way Bendō-wa All buddha tathagatas who individually transmit inconceivable dharma, actualizing unsurpassable, complete enlightenment, have a wondrous art, supreme and unconditioned. Receptive samadhi is its mark; only buddhas transmit it to buddhas without veering off. Sitting upright, practicing Zen, is the authentic gate to free yourself in the unconfined realm of this samadhi. Although this inconceivable dharma is abundant in each person, it is not actualized without practice, and it is not experienced without realization. When you release it, it fills your hand—how could it be limited to one or many? When you speak it, it fills your mouth—it is not bounded by length or width. All buddhas continuously abide in this dharma, and do not leave traces of consciousness about where they are. Sentient beings continuously move about in this dharma, but where they are is not clear in their consciousness. The concentrated endeavor of the way I am speaking of allows all things to come forth in realization to practice going beyond in the path of letting go. Passing through the barrier [of dualism] and dropping off limitations in this way, how could you be hindered by nodes in bamboo or knots in wood [concepts and theories]? * After the aspiration for enlightenment arose, I began to search for dharma, visiting teachers at various places in our country. Then I met priest Myozen, of the Kennin Monastery, with whom I trained for nine years, and thus I learned a little about the teaching of the Rinzai School. Priest Myozen alone, as a senior disciple of ancestor Eisai, authentically received transmittion of the unsurpassable buddha dharma from him; no one can be compared with him. -

Seon Dialogues 禪語錄禪語錄 Seonseon Dialoguesdialogues John Jorgensen

8 COLLECTED WORKS OF KOREAN BUDDHISM 8 SEON DIALOGUES 禪語錄禪語錄 SEONSEON DIALOGUESDIALOGUES JOHN JORGENSEN COLLECTED WORKS OF KOREAN BUDDHISM VOLUME 8 禪語錄 SEON DIALOGUES Collected Works of Korean Buddhism, Vol. 8 Seon Dialogues Edited and Translated by John Jorgensen Published by the Jogye Order of Korean Buddhism Distributed by the Compilation Committee of Korean Buddhist Thought 45 Gyeonji-dong, Jongno-gu, Seoul, 110-170, Korea / T. 82-2-725-0364 / F. 82-2-725-0365 First printed on June 25, 2012 Designed by ahn graphics ltd. Printed by Chun-il Munhwasa, Paju, Korea © 2012 by the Compilation Committee of Korean Buddhist Thought, Jogye Order of Korean Buddhism This project has been supported by the Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism, Republic of Korea. ISBN: 978-89-94117-12-6 ISBN: 978-89-94117-17-1 (Set) Printed in Korea COLLECTED WORKS OF KOREAN BUDDHISM VOLUME 8 禪語錄 SEON DIALOGUES EDITED AND TRANSLATED BY JOHN JORGENSEN i Preface to The Collected Works of Korean Buddhism At the start of the twenty-first century, humanity looked with hope on the dawning of a new millennium. A decade later, however, the global village still faces the continued reality of suffering, whether it is the slaughter of innocents in politically volatile regions, the ongoing economic crisis that currently roils the world financial system, or repeated natural disasters. Buddhism has always taught that the world is inherently unstable and its teachings are rooted in the perception of the three marks that govern all conditioned existence: impermanence, suffering, and non-self. Indeed, the veracity of the Buddhist worldview continues to be borne out by our collective experience today. -

Buddhist Studies

Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies Volume 24 • Number 1 • 2001 MINORUHARA In memoriam J.W. de Jong 1 JINHUA JIA Doctrinal Reformation of the Hongzhou School of Chan Buddhism 7 NADINE OWEN Constructing Another Perspective for Ajanta's Fifth-Century Excavations 27 PETER VERHAGEN Studies in Indo-Tibetan Buddhist Hermeneutics (1) Issues of Interpretation and Translation in the Minor Works of Si-tu Pan-chen Chos-kyi-'byun-gnas (16997-1774) 61 GLENN WALLIS The Buddha's Remains: mantra in the ManjusrTmulakalpa 89 BOOK REVIEW by ULRICH PAGEL Heinz Bechert [et al.]: Der Buddhismus I: Der Indische Buddhismus und seine Verzweigungen 127 Treasurer's Report 2000 135 JINHUA JIA Doctrinal Reformation of the Hongzhou School of Chan Buddhism* Hu Shi asserts that "Chinese" Chan proper first took on complete shape in the Hongzhou school.1 This assertion has been generally accepted, and the Hongzhou school is regarded as the beginning of "classical" or "golden-age" Chan. However, when discussing exactly what marks the beginning of this new type of Chan, or in other words, what kind of reformation Mazu Daoyi JSffill-- (709-88) brought to the Chan tradition, there have been quite different explanations. YANAGIDA Seizan |7PEBIIll[ posits that the m6st salient characteristic of the Hong zhou school is that it is a Chan of everyday life and a religion of humanity.2 IRIYA Yoshitaka A^ilfij regards the ideas, "function is identical with [Buddha-]nature" and "daily activities are wonderful functions," as the core of Daoyi's teaching.3 John McRAE assumes that "encounter dialogue" distinguishes the "classical" Chan of Mazu from the "pre-classical" Chan of the Northern, early Southern, and Niutou schools.4 Bernard FAURE takes the disappearance of one-practice samadhi (yixing sanmei — ffzLW) as "an indicator of the 'epistemologi- cal split' that opened between early Chan and the 'classical' Chan of the * I thank Professors Paul W. -

Soto Zen: an Introduction to Zazen

SOT¯ O¯ ZEN An Introduction to Zazen SOT¯ O¯ ZEN: An Introduction to Zazen Edited by: S¯ot¯o Zen Buddhism International Center Published by: SOTOSHU SHUMUCHO 2-5-2, Shiba, Minato-ku, Tokyo 105-8544, Japan Tel: +81-3-3454-5411 Fax: +81-3-3454-5423 URL: http://global.sotozen-net.or.jp/ First printing: 2002 NinthFifteenth printing: printing: 20122017 © 2002 by SOTOSHU SHUMUCHO. All rights reserved. Printed in Japan Contents Part I. Practice of Zazen....................................................7 1. A Path of Just Sitting: Zazen as the Practice of the Bodhisattva Way 9 2. How to Do Zazen 25 3. Manners in the Zend¯o 36 Part II. An Introduction to S¯ot¯o Zen .............................47 1. History and Teachings of S¯ot¯o Zen 49 2. Texts on Zazen 69 Fukan Zazengi 69 Sh¯ob¯ogenz¯o Bend¯owa 72 Sh¯ob¯ogenz¯o Zuimonki 81 Zazen Y¯ojinki 87 J¯uniji-h¯ogo 93 Appendixes.......................................................................99 Takkesa ge (Robe Verse) 101 Kaiky¯o ge (Sutra-Opening Verse) 101 Shigu seigan mon (Four Vows) 101 Hannya shingy¯o (Heart Sutra) 101 Fuek¯o (Universal Transference of Merit) 102 Part I Practice of Zazen A Path of Just Sitting: Zazen as the 1 Practice of the Bodhisattva Way Shohaku Okumura A Personal Reflection on Zazen Practice in Modern Times Problems we are facing The 20th century was scarred by two World Wars, a Cold War between powerful nations, and countless regional conflicts of great violence. Millions were killed, and millions more displaced from their homes. All the developed nations were involved in these wars and conflicts.