Book Review by Ina Lipkowitz Nathan Macdonald, What Did the Ancient

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1) Meeting Your Bible 2) Discussing the Bible (Breakout Rooms for 10

Wednesday Wellspring: A Bible Study for UU’s (part 1) Bible Study 101: Valuable Information for Serious Students taught by Keith Atwater, American River College worksheet / discussion topics / study guide 1) Meeting Your Bible What is your Bible’s full title, publisher, & publication date? Where did you get your Bible? (source, price, etc.) What’s your Bible like? (leather cover, paperback, old, new, etc.) Any Gospels words in red? What translation is it? (King James, New American Standard, Living Bible, New International, etc.) Does your Bible include Apocrypha?( Ezra, Tobit, Maccabees, Baruch) Preface? Study Aids? What are most common names for God used in your edition? (Lord, Jehovah, Yahweh, God) The Bible in your hands, in book form, with book titles, chapter and verse numbers, page numbers, in a language you can read, at a reasonably affordable price, is a relatively recent development (starting @ 1600’s). A Bible with cross-references, study aids, footnotes, commentary, maps, etc. is probably less than 50 years old! Early Hebrew (Jewish) Bible ‘books’ (what Christians call the Old Testament) were on 20 - 30 foot long scrolls and lacked not only page numbers & chapter indications but also had no punctuation, vowels, and spaces between words! The most popular Hebrew (Jewish) Bible @ the time of Jesus was the “Septuagint” – a Greek translation. Remember Alexander the Great conquered the Middle East and elsewhere an “Hellenized’ the ‘Western world.’ 2) Discussing the Bible (breakout rooms for 10 minutes. Choose among these questions; each person shares 1. Okay one bullet point to be discussed, but please let everyone say something!) • What are your past experiences with the Bible? (e.g. -

Tanakh Versus Old Testament

Tanakh versus Old Testament What is the Tanakh? The Tanakh (also known as the Hebrew Bible) was originally written in Hebrew with a few passages in Aramaic. The Tanakh is divided into three sections – Torah (Five Books of Moshe), Nevi’im (Prophets), and Ketuvim (Writings). The Torah is made up of five books that were given to Moshe directly from God after the Exodus from Mitzrayim. The Torah was handed down through the successive generations from the time of Moshe. The Torah includes the creation of the earth and the first humans, the Great Flood and the covenant with the gentiles, the Hebrew enslavement and Exodus of the Hebrews from Mitzrayim, giving of the Torah, renewal of Covenant given to Avraham, establishment of the festivals, wandering through the desert, the Mishkan, Ark, and Priestly duties, and the death of Moshe. The Nevi’im covers the time period from the death of Moshe through the Babylonian exile and contains 19 books. The Nevi’im includes the time of the Hebrews entering Eretz Yisrael, the conquest of Yericho, the conquest of Eretz Yisrael and its division among the tribes, the judicial system, Era of Shaul and David, Shlomo’s wisdom and the construction of the First Beit HaMikdash, kings of Yisrael and Yehuda, prophecy, messianic prophecies, and the Babylonian exile. The Ketuvim covers the period after the return from the Babylonian exile and contains 11 books. The Ketuvim is made up of various writings that do not have an overall theme. This section of the Tanakh includes poems and songs, the stories of Iyov, Rut, and Ester, the writings and prophecies of Dani’el, and the history of the kings of Yisrael and Yehuda. -

2 the Assyrian Empire, the Conquest of Israel, and the Colonization of Judah 37 I

ISRAEL AND EMPIRE ii ISRAEL AND EMPIRE A Postcolonial History of Israel and Early Judaism Leo G. Perdue and Warren Carter Edited by Coleman A. Baker LONDON • NEW DELHI • NEW YORK • SYDNEY 1 Bloomsbury T&T Clark An imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc Imprint previously known as T&T Clark 50 Bedford Square 1385 Broadway London New York WC1B 3DP NY 10018 UK USA www.bloomsbury.com Bloomsbury, T&T Clark and the Diana logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc First published 2015 © Leo G. Perdue, Warren Carter and Coleman A. Baker, 2015 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publishers. Leo G. Perdue, Warren Carter and Coleman A. Baker have asserted their rights under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as Authors of this work. No responsibility for loss caused to any individual or organization acting on or refraining from action as a result of the material in this publication can be accepted by Bloomsbury or the authors. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN: HB: 978-0-56705-409-8 PB: 978-0-56724-328-7 ePDF: 978-0-56728-051-0 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. Typeset by Forthcoming Publications (www.forthpub.com) 1 Contents Abbreviations vii Preface ix Introduction: Empires, Colonies, and Postcolonial Interpretation 1 I. -

The Hebrew Revolution and the Revolution of the Hebrew Language Between the 1880S and the 1930S

The Hebrew Revolution and the Revolution of the Hebrew Language between the 1880s and the 1930s Judith Winther Copenhagen The new Hebrew culture which began to crys- Eliezer Ben Yehudah was born in 1858, tallize in the land of Israel from the end of the Ben Gurion in 1886, and Berl Kazenelson in last century, is a successful event of "cultural 1887. planning". During a relatively short period of As a man who was not active in the so- time a little group of"culture planners" succee- cialist Jewish movement Ben Yehudah's dedi- ded in creating a system which in a significant cation to Hebrew is probably comprehensible. way was adapted to the requested Zionist ide- But why should a prominent socialist like Berl ology. The fact that the means by which the Kazenelson stick to the spoken Hebrew langu- "cultural planning" was realized implicated a age? A man, who prior to his immigration to heroic presentation of the happenings that led Palestine was an anti-Zionist, ridiculed Hebrew to a pathetical view of the development. It and was an enthusiastic devotee of Yiddish? presented the new historical ocurrences in Pa- The explanation is to be found in the vi- lestine as a renaissance and not as a continu- tal necessity which was felt by the pioneers ation of Jewish history, as a break and not as of the second Aliyah to achieve at all costs a continuity of the past. break from the past, from the large world of the The decision to create a political and a Russian revolutionary movements, from Rus- Hebrew cultural renaissance was laid down by sian culture, and Jewish Russian culture. -

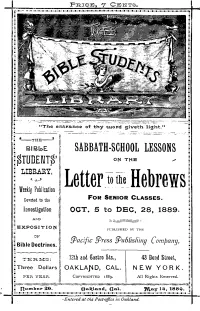

Letter to the Hebrews

7 CLI-rs. 11,1•. 1 •112,12 . 1 •.•.i.M.1211•11.1112 .11111 •11•11 •11. 411•11 .11•11•11 .1 .1.11 •11 •11211.1.11•11.1121.•.•111.11•11......111....... "The entrance of thy word giveth light." BIBLDE SABBATH-SCHOOL LESSONS TUDENTS' TtlE LIBRARY, o the weekti Publication I Letter t Hebrews Devoted to the FOR SENIOR CLASSES. Investigation :3 OCT. 5 to DEC, 28, 1889. AND 1 EXPOSITION PUBLISHED IsY THE OF .acific gress guNishinll Company, :Bible Doctrines. 12th and eastro Sts., 43 Bond Street, :Three Dollars OAKLAJ1D, CAL. NEW YORK. • PER YEAR. • COPYRIGHTED 1889. All Rights Reserved. • number 20. Oakland, Gal. 2otay 114, 1889. : ▪ •„. ,.1•11•11. •11•11..1•11•11.11.112 1 .11 2 11 •11.11.11•11•11•11.11•11•11•11.11•11•11•11.111. taii•rin .112 -Entered at the Post-office in Oakland. • T H BIBLE STUDENTS' UNARY. The Following Numbers are now Ready, and will be Sent Post-paid on Receipt of Price: No. r. Bible Sanctification. Price, zo cents. No. 2. Abiding Sabbath and Lord's Day. Price, 20 cents. No. 3. Views of National Reform, Series I. Price, 15 cents. No. g. The Saints' Inheritance. Price, zo cents. No. S. The Judgment. Price, 2 cents. No. 6. The Third Angel's Message. Price, ¢ cents. No. 7. The Definite Seventh Day. Price, 2 cents. No. 8. S. S. Lessons: Subject, Tithes and Offerings. Price, 5 cents. No. 9. The Origin and Growth. of Sunday Observance. Price, zo cents. No. iv. -

1. from Ur to Canaan

Copyrighted Material 1. FromUrtoCanaan A WANDERINg PEOPLE In the beginning there were wanderings. The first human -be ings, Adam and Eve, are banished from Gan Eden, from Paradise. The founder of monotheism, Abraham, follows God’s com- mand, “Lech lecha” (“Go forth”), and takes to wandering from his home, Ur in Mesopotamia, eventually reaching the land of Canaan, whence his great-grandson Joseph will, in turn, depart for Egypt. Many generations later Moses leads the Jews back to the homeland granted them, which henceforth will be given the name “Israel,” the second name of Abraham’s grandson Jacob. So at least we are told in the Hebrew Bible, certainly the most successful and undoubtedly the most influential book in world literature. Its success story is all the more astonishing when one considers that this document was not composed by one of the powerful nations of antiquity, such as the Egyptians or Assyr- ians, the Persians or Babylonians, the Greeks or Romans, but by a tiny nation that at various times in the course of its history was dominated by all of the above-mentioned peoples. And yet it was precisely this legacy of the Jews that, with the spread of Christianity and Islam, became the foundation for the literary and religious inheritance of the greater part of humanity. By Copyrighted Material 2 C H A P T E R 1 this means, too, the legendary origins of the Jews told in the Bible attained worldwide renown. The Hebrew Bible, which would later be called the Old Testament in Christian parlance, contains legislative precepts, wisdom literature, moral homilies, love songs, and mystical vi- sions, but it also has books meant to instruct us about historical events. -

LEARNING HOW to READ the BIBLE the Bible

The Story LEARNING HOW TO READ THE BIBLE The Bible Compelling, but confusing … and often boring The bible is a small library of books • OLD TESTAMENT (“Hebrew Scriptures”) • Many different authors • Different styles / literary types (genres) • 611,000 words in Hebrew • 39 books in the shared canon • written in Aramaic & Hebrew • 7 additional books in the second canon (Deuteronomical) of the Catholic Church • written mostly in Greek • OLD TESTAMENT (“Hebrew Scriptures”) • Christian (English) bibles are arranged like the Septuagint / LXX (3rd C. BC) Greek translation • Organised into 4 sections Pentateuch History Wisdom Prophets (Torah / Law) Joshua, Judges Job Isaiah Genesis Ruth Psalms Jeremiah Exodus 1-2 Samuel Proverbs Lamentations Leviticus 1-2 Kings Ecclesiastes Ezekiel Numbers 1-2 Chronicles Song of Songs Daniel, Deuteronomy Ezra Hosea, Joel, Nehemiah Amos, Obadiah, Esther Jonah, Micah, Nahum, Habakkuk, Zephaniah, Haggai, Zechariah, Malachi Hebrew Bible (based on Septuagint order) 39 books Including Deuterocanonical books = 46 books in Catholic OT Genesis Joshua Job Isaiah Exodus Judges Psalms Jeremiah Proverbs Lamentations Leviticus Ruth Ecclesiastes Ezekiel Numbers 1 SamuelSamuel2 Samuel Song of Songs DanielDaniel + Deuteronomy 1 KingsKings2 Kings Wisdom 12 Minor Prophets 1 Chron 2 Chron Hosea, Joel, Amos, Chronicles Obadiah, Jonah, Micah, Sirach Nahum, Habakkuk, Ezra Nehemiah Zephaniah, Haggai, Ezra - Nehemiah Zechariah, Malachi Tobit Judith EstherEsther + 1 Macc 2 Macc KETUVIM NEVI’IM PentateuchTORAH History Wisdom Prophets Ta(Torah -

Timeline of Ancient Israel Where Is Canaan? Video: Israelites in Egypt

Timeline of Ancient Israel Where is Canaan? Video: Israelites in Egypt 1. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CpR2YxS0CTM https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=d90NM9tgDQE The Hebrews and Judaism (pg. 40 – 45) The Hebrews and Judaism: The Hebrew history is told through the Bible and other books of the Old Testament and Jewish faith AbrahamIsaacJacob12 sons=12 tribes of Israel Abraham (patriarch): Covenant with God which states two beliefs: - Special relationship with Abraham and his ancestors - Canaan is the “promised land” and belongs to the Hebrews - Importantly, the Jews are monotheistic The Hebrews and Judaism (pg. 40 – 45) The Hebrews eventually end up in Egypt Joseph – one of Jacob’s sons helps the Pharaoh through a famine The Israelites become enslaved in Egypt Who leads them out of Egypt and into the “promised land”? The Hebrews and Judaism (pg. 40 – 45) Moses leads the Israelites back to Canaan - after 40 years! Kingdom of Israel (~ 1000 B.C.) - Jerusalem is the capital - It is very much like other kingdoms of its day, but smaller - The Israelites are eventually conquered: 722 B.C. the Northern half is conquered by the Assyrians 586 B.C. the Babylonians conquer the rest and put them in captivity 539 B.C. the Persians defeat the Babylonians and free the Israelites The Hebrews and Judaism (pg. 40 – 45) The Hebrews have two great legacies: Their laws – the Bible and the Torah and their ethics Their laws become the basis of two other major monotheistic religions – Christianity and Islam They demonstrate many of the moral foundations we follow today – such as treating everyone equally Their laws and ethics can also be found deeply rooted in our democratic society In-Class Assignment & Homework Read sections 2.3 (Hebrews) & 2.4 (Egyptians) in the e-book. -

“Food for Peace”: the Vegan Religion of the Hebrews of Jerusalem

IDEA – Studia nad strukturą i rozwojem pojęć filozoficznych XXVI Białystok 2014 SHELLEY ELKAYAM (Getynga, Niemcy, Jerozolima, Izrael) “FOOD FOR PEACE”: THE VEGAN RELIGION OF THE HEBREWS OF JERUSALEM Food, eschatology and sacred chronology Abraham Elqayam, a great scholar of Jewish mysticism and Jewish Philos- ophy, presented food as key in designing sacred chronology 1 (2006:239). Ruth Tsoffar Mizrahi, who studies Israeli society and culture, argues that in Jewish culture ‘eating’ is ‘believing’ (2006:35), just as in American culture ‘seeing is be- lieving’. (Dundes 1977). Such usage of ‘eating’ as ‘believing’ appears commonly within today’s Hebrew slang. Eating has a religious context of accepting, such as in the Passover ceremony where ‘eating’ becomes ‘believing’ through the symbolic food set on Passover table – from haroset (a blend of fruits and nuts) to maror (bitter herbs) to matza (unleavened bread). These Hebrew words point to specific foods of Passover that serve as instrumental symbols in a ‘tactile’ conservation and in the memorizing of religious collective experience. In this paper I will elu- cidate three major messianic ‘tactile’ terms in the African Hebrew Israelites of Jerusalem (AHIJ) religion: Food and Bio-Evolution. The African Hebrew Israelites of Jerusalem The African Hebrew Israelites of Jerusalem (AHIJ) re-emerged during the civil rights movement, in a time when black pride was salient amongst political 1 Sacred chronology is the system of holidays and Shabbat. For example, for Sabbatians in Shabbat there are three meals: Friday evening, Saturday breakfast and Saturday lunch. See Elqayam’s discussion on the Freedom Redemption via food, where the redemption of the individual and the community go through eating the “sacred meat” (Elqayam 2006:243–248). -

Igbos: the Hebrews of West Africa

Igbos: The Hebrews of West Africa by Michelle Lopez Wellansky Submitted to the Board of Humanities School of SUY Purchase in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts Purchase College State University of New York May 2017 Sponsor: Leandro Benmergui Second Reader: Rachel Hallote 1 Igbos: The Hebrews of West Africa Michelle Lopez Wellansky Introduction There are many groups of people around the world who claim to be Jews. Some declare they are descendants of the ancient Israelites; others have performed group conversions. One group that stands out is the Igbo people of Southeastern Nigeria. The Igbo are one of many groups that proclaim to make up the Diasporic Jews from Africa. Historians and ethnographers have looked at the story of the Igbo from different perspectives. The Igbo people are an ethnic tribe from Southern Nigeria. Pronounced “Ee- bo” (the “g” is silent), they are the third largest tribe in Nigeria, behind the Hausa and the Yoruba. The country, formally known as the Federal Republic of Nigeria, is in West Africa on the Atlantic Coast and is bordered by Chad, Cameroon, Benin, and Niger. The Igbo make up about 18% of the Nigerian population. They speak the Igbo language, which is part of the Niger-Congo language family. The majority of the Igbo today are practicing Christians. Though they identify as Christian, many consider themselves to be “cultural” or “ethnic” Jews. Additionally, there are more than two million Igbos who practice Judaism while also reading the New Testament. In The Black -

The Meaning of the Word “Hebrew” in Genesis Rick Aschmann

Bible chronology main page Last updated: 16-May-2020 at 14:54 (See History.) Español © Richard P. Aschmann The Meaning of the Word “Hebrew” in Genesis Rick Aschmann (Aschmann.net/BibleChronology/HebrewInGenesis.pdf) 1. In the Old Testament “Hebrew” never refers to the Hebrew language. .................................................................................... 1 2. By the time of the New Testament “Hebrew” did normally refer to the Hebrew or Aramaic languages................................... 2 3. In the Old Testament “Hebrew” is almost always used in interaction with foreigners. ............................................................ 2 4. In Genesis “Hebrew” is not limited to the Israelites, but refers to some larger group that includes them! ................................ 3 5. Could “Hebrew” be the same as Habiru? ............................................................................................................................... 4 1. In the Old Testament “Hebrew” never refers to the Hebrew language. Nowadays the word “Hebrew” refers to the language of the ancient Israelites, which was a variety of the ancient Canaanite language, and to its modern descendant which is the official language of the state of Israel. However, in the Old Testament, the word “Hebrew” never has this meaning. Prior to the book of 2 Kings the language is never named, and after that point it is usually called “the language of Judah”. What it was called before the division of the kingdom at the death of Solomon is unknown. It may have been called “the language of Israel”, though we have no evidence of this. However, it is called “the language of Canaan” once in the Old Testament, in Isaiah 19:18, and this may have been what it was called all along. יְהּוד ִ֔ית שְפ ַ֣ת נכְ ִ֔ען יְהּוד ִ֔ית Hebrew form Pronunciation /yəhūˈḏîṯ/ /śəˈp̄ aṯ kəˈnaʿan/ /yəhūˈḏîṯ/ Literal meaning (language) of Judah language of Canaan (language) of Judah References 2 Kings 18:26, 28, Isa. -

Jesus and the Temple in John and Hebrews: Towards a New Testament Perspective

DavarLogos 2016 - Vol. XV - N.º 2 Artículo Jesus and the Temple in John and Hebrews: Towards a New Testament Perspective Eliezer González Resumen En los últimos años, la definición que Jesús dio de sí mismo en los evangelios, particu- larmente en el de Juan, como el nuevo templo ha recibido atención erudita significativa. No solo Jesús parece declarar ser un templo. También anuncia el reemplazo del templo de Jerusalén como siendo fundado en su persona en un contexto escatológico (ej. Juan 2,19-21). Es más: este concepto es desarrollado de manera más completa en las epístolas de Pablo, cuando declaran que el nuevo templo es fundado en la persona de Cristo, y es, de hecho, el cuerpo de Cristo, su iglesia. Este artículo explora y desarrolla el concepto de Jesucristo como el nuevo templo, con un enfoque particular en Juan 4,7-26. La tesis principal de esta investigación es que la decla- ración de Jesús de sí mismo como el templo, y el desarrollo subsecuente de Pablo de este concepto, debe recibir el peso que les corresponde. Dicha declaración tiene implicacio- nes significativas para la autocomprensión de la iglesia hoy, y para entender la naturaleza misma de la adoración cristiana, iluminando muchos temas neotestamentarios desde una perspectiva cristológica. Palabras clave Evangelio de Juan - Pablo - Templo – Hermenéutica - Cristología Abstract In recent years, the notion of Jesus’ definition of Himself as the New Temple in the Gos- pels, and particularly in the Gospel of John, has received significant scholarly attention. Not only does Jesus appear to declare Himself to be a temple, but He also foreshadows the replacement of the Jerusalem Temple as being founded in His own person in an eschato- logical context (e.g.