The Meaning of the Word “Hebrew” in Genesis Rick Aschmann

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1) Meeting Your Bible 2) Discussing the Bible (Breakout Rooms for 10

Wednesday Wellspring: A Bible Study for UU’s (part 1) Bible Study 101: Valuable Information for Serious Students taught by Keith Atwater, American River College worksheet / discussion topics / study guide 1) Meeting Your Bible What is your Bible’s full title, publisher, & publication date? Where did you get your Bible? (source, price, etc.) What’s your Bible like? (leather cover, paperback, old, new, etc.) Any Gospels words in red? What translation is it? (King James, New American Standard, Living Bible, New International, etc.) Does your Bible include Apocrypha?( Ezra, Tobit, Maccabees, Baruch) Preface? Study Aids? What are most common names for God used in your edition? (Lord, Jehovah, Yahweh, God) The Bible in your hands, in book form, with book titles, chapter and verse numbers, page numbers, in a language you can read, at a reasonably affordable price, is a relatively recent development (starting @ 1600’s). A Bible with cross-references, study aids, footnotes, commentary, maps, etc. is probably less than 50 years old! Early Hebrew (Jewish) Bible ‘books’ (what Christians call the Old Testament) were on 20 - 30 foot long scrolls and lacked not only page numbers & chapter indications but also had no punctuation, vowels, and spaces between words! The most popular Hebrew (Jewish) Bible @ the time of Jesus was the “Septuagint” – a Greek translation. Remember Alexander the Great conquered the Middle East and elsewhere an “Hellenized’ the ‘Western world.’ 2) Discussing the Bible (breakout rooms for 10 minutes. Choose among these questions; each person shares 1. Okay one bullet point to be discussed, but please let everyone say something!) • What are your past experiences with the Bible? (e.g. -

Bible Studies

BIBLE STUDIES " Now these were more noble than those in Thessalonica, in that they received the word with all readiness of mind, examining the Scriptures daily, whether these things were so " (Acts 17. 11). SOME IMPORTANT CITIES OF SCRIPTURE NOTES ON THE PSALMS VOLUME 33 Published by NEEDED TRUTH PUBLISHING OFFICE ASSEMBLY HALL, GEORGE LANE HAYES. BROMLEY, KENT. CONTENTS STUDY SUBJECT Some important Cities of Scripture Nineveh 3 The Cities of the Plain 20 Bethlehem 37 Jericho 53 Bethel 67 Hebron 86, 122 Samaria 99, 122 Babylon (Old Testament) 116 Babylon (Future) 131 Jerusalem (Old Testament) 142 Jerusalem (From the Birth of Christ to the Millenium).. 154 The New Jerusalem 166 Editorials.... 1, 17, 33, 49, 65, 81, 97, 113, 129, 141, 153, 165 Comments.... 10, 28, 44, 60, 74, 92, 107, 123, 136, 147, 159, 170 Questions and Answers 12, 30, 75, 94, 108, 160, 173 Other Contributions Babylon (Old Testament) 115 Bethlehem 37 Chronology of the Times of the Patriarchs 34 Hebron-Zion....... 83 Nineveh, The Burden of 2 Noah, Study Impressions of the Times of.... 149, 162, 174 Plain, The Cities of the 18 Plains, The 50 Psalms, Notes on the 12, 31, 45, 61, 76, 95, 109, 123, 139, 150, 164, 175 Zacchaeus 51 BIBLE STUDIES Now these were more noble than those in Thessalonica, in that they received the word with all readiness of mind, examining the Scriptures daily, whether these things were so*' (Acts 17. 11). VOLUME 33 JANUARY 1965 EDITORIAL We now begin a study somewhat different in nature from those that have engaged our attention in recent years. -

Tanakh Versus Old Testament

Tanakh versus Old Testament What is the Tanakh? The Tanakh (also known as the Hebrew Bible) was originally written in Hebrew with a few passages in Aramaic. The Tanakh is divided into three sections – Torah (Five Books of Moshe), Nevi’im (Prophets), and Ketuvim (Writings). The Torah is made up of five books that were given to Moshe directly from God after the Exodus from Mitzrayim. The Torah was handed down through the successive generations from the time of Moshe. The Torah includes the creation of the earth and the first humans, the Great Flood and the covenant with the gentiles, the Hebrew enslavement and Exodus of the Hebrews from Mitzrayim, giving of the Torah, renewal of Covenant given to Avraham, establishment of the festivals, wandering through the desert, the Mishkan, Ark, and Priestly duties, and the death of Moshe. The Nevi’im covers the time period from the death of Moshe through the Babylonian exile and contains 19 books. The Nevi’im includes the time of the Hebrews entering Eretz Yisrael, the conquest of Yericho, the conquest of Eretz Yisrael and its division among the tribes, the judicial system, Era of Shaul and David, Shlomo’s wisdom and the construction of the First Beit HaMikdash, kings of Yisrael and Yehuda, prophecy, messianic prophecies, and the Babylonian exile. The Ketuvim covers the period after the return from the Babylonian exile and contains 11 books. The Ketuvim is made up of various writings that do not have an overall theme. This section of the Tanakh includes poems and songs, the stories of Iyov, Rut, and Ester, the writings and prophecies of Dani’el, and the history of the kings of Yisrael and Yehuda. -

2 the Assyrian Empire, the Conquest of Israel, and the Colonization of Judah 37 I

ISRAEL AND EMPIRE ii ISRAEL AND EMPIRE A Postcolonial History of Israel and Early Judaism Leo G. Perdue and Warren Carter Edited by Coleman A. Baker LONDON • NEW DELHI • NEW YORK • SYDNEY 1 Bloomsbury T&T Clark An imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc Imprint previously known as T&T Clark 50 Bedford Square 1385 Broadway London New York WC1B 3DP NY 10018 UK USA www.bloomsbury.com Bloomsbury, T&T Clark and the Diana logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc First published 2015 © Leo G. Perdue, Warren Carter and Coleman A. Baker, 2015 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publishers. Leo G. Perdue, Warren Carter and Coleman A. Baker have asserted their rights under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as Authors of this work. No responsibility for loss caused to any individual or organization acting on or refraining from action as a result of the material in this publication can be accepted by Bloomsbury or the authors. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN: HB: 978-0-56705-409-8 PB: 978-0-56724-328-7 ePDF: 978-0-56728-051-0 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. Typeset by Forthcoming Publications (www.forthpub.com) 1 Contents Abbreviations vii Preface ix Introduction: Empires, Colonies, and Postcolonial Interpretation 1 I. -

The Hebrew Revolution and the Revolution of the Hebrew Language Between the 1880S and the 1930S

The Hebrew Revolution and the Revolution of the Hebrew Language between the 1880s and the 1930s Judith Winther Copenhagen The new Hebrew culture which began to crys- Eliezer Ben Yehudah was born in 1858, tallize in the land of Israel from the end of the Ben Gurion in 1886, and Berl Kazenelson in last century, is a successful event of "cultural 1887. planning". During a relatively short period of As a man who was not active in the so- time a little group of"culture planners" succee- cialist Jewish movement Ben Yehudah's dedi- ded in creating a system which in a significant cation to Hebrew is probably comprehensible. way was adapted to the requested Zionist ide- But why should a prominent socialist like Berl ology. The fact that the means by which the Kazenelson stick to the spoken Hebrew langu- "cultural planning" was realized implicated a age? A man, who prior to his immigration to heroic presentation of the happenings that led Palestine was an anti-Zionist, ridiculed Hebrew to a pathetical view of the development. It and was an enthusiastic devotee of Yiddish? presented the new historical ocurrences in Pa- The explanation is to be found in the vi- lestine as a renaissance and not as a continu- tal necessity which was felt by the pioneers ation of Jewish history, as a break and not as of the second Aliyah to achieve at all costs a continuity of the past. break from the past, from the large world of the The decision to create a political and a Russian revolutionary movements, from Rus- Hebrew cultural renaissance was laid down by sian culture, and Jewish Russian culture. -

1 Genesis 10-‐11 Study ID#12ID1337 Alright, Shall We Open Our Bibles

Genesis 10-11 Study ID#12ID1337 Alright, shall we open our Bibles tonight to Genesis 10. If you're just joining us on Wednesday, you're only nine chapters behind. So you can catch up, all of those are online, they are in video, they are on audio. We are working on translating all of our studies online into Spanish. It'll take awhile, but it's being done. We are also transcribing every study so that you can have a written copy of all that's said. You won't have to worry about notes. It'll all be there, the Scriptures will be there. So that's also in the process. It'll take awhile, but that's the goal and the direction we're heading. So you can keep that in your prayers. Tonight we want to continue in our in-depth study of this book of beginnings, the book of Genesis, and we've seen a lot if you've been with us. We looked at the beginning of the earth, and the beginning of the universe, and the beginning of mankind, and the origin of marriage, and the beginning of the family, and the beginning of sacrifice and worship, and the beginning of the gospel message, way back there in Chapter 3, verse 15, when the LORD promised One who would come that would crush the head of the serpent, preached in advance. We've gone from creation to the fall, from the curse to its conseQuences. We watched Abel and then Cain in a very ungodly line that God doesn't track very far. -

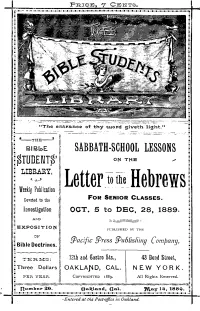

Letter to the Hebrews

7 CLI-rs. 11,1•. 1 •112,12 . 1 •.•.i.M.1211•11.1112 .11111 •11•11 •11. 411•11 .11•11•11 .1 .1.11 •11 •11211.1.11•11.1121.•.•111.11•11......111....... "The entrance of thy word giveth light." BIBLDE SABBATH-SCHOOL LESSONS TUDENTS' TtlE LIBRARY, o the weekti Publication I Letter t Hebrews Devoted to the FOR SENIOR CLASSES. Investigation :3 OCT. 5 to DEC, 28, 1889. AND 1 EXPOSITION PUBLISHED IsY THE OF .acific gress guNishinll Company, :Bible Doctrines. 12th and eastro Sts., 43 Bond Street, :Three Dollars OAKLAJ1D, CAL. NEW YORK. • PER YEAR. • COPYRIGHTED 1889. All Rights Reserved. • number 20. Oakland, Gal. 2otay 114, 1889. : ▪ •„. ,.1•11•11. •11•11..1•11•11.11.112 1 .11 2 11 •11.11.11•11•11•11.11•11•11•11.11•11•11•11.111. taii•rin .112 -Entered at the Post-office in Oakland. • T H BIBLE STUDENTS' UNARY. The Following Numbers are now Ready, and will be Sent Post-paid on Receipt of Price: No. r. Bible Sanctification. Price, zo cents. No. 2. Abiding Sabbath and Lord's Day. Price, 20 cents. No. 3. Views of National Reform, Series I. Price, 15 cents. No. g. The Saints' Inheritance. Price, zo cents. No. S. The Judgment. Price, 2 cents. No. 6. The Third Angel's Message. Price, ¢ cents. No. 7. The Definite Seventh Day. Price, 2 cents. No. 8. S. S. Lessons: Subject, Tithes and Offerings. Price, 5 cents. No. 9. The Origin and Growth. of Sunday Observance. Price, zo cents. No. iv. -

Heavenly Priesthood in the Apocalypse of Abraham

HEAVENLY PRIESTHOOD IN THE APOCALYPSE OF ABRAHAM The Apocalypse of Abraham is a vital source for understanding both Jewish apocalypticism and mysticism. Written anonymously soon after the destruction of the Second Jerusalem Temple, the text envisions heaven as the true place of worship and depicts Abraham as an initiate of the celestial priesthood. Andrei A. Orlov focuses on the central rite of the Abraham story – the scapegoat ritual that receives a striking eschatological reinterpretation in the text. He demonstrates that the development of the sacerdotal traditions in the Apocalypse of Abraham, along with a cluster of Jewish mystical motifs, represents an important transition from Jewish apocalypticism to the symbols of early Jewish mysticism. In this way, Orlov offers unique insight into the complex world of the Jewish sacerdotal debates in the early centuries of the Common Era. The book will be of interest to scholars of early Judaism and Christianity, Old Testament studies, and Jewish mysticism and magic. ANDREI A. ORLOV is Professor of Judaism and Christianity in Antiquity at Marquette University. His recent publications include Divine Manifestations in the Slavonic Pseudepigrapha (2009), Selected Studies in the Slavonic Pseudepigrapha (2009), Concealed Writings: Jewish Mysticism in the Slavonic Pseudepigrapha (2011), and Dark Mirrors: Azazel and Satanael in Early Jewish Demonology (2011). Downloaded from Cambridge Books Online by IP 130.209.6.50 on Thu Aug 08 23:36:19 WEST 2013. http://ebooks.cambridge.org/ebook.jsf?bid=CBO9781139856430 Cambridge Books Online © Cambridge University Press, 2013 HEAVENLY PRIESTHOOD IN THE APOCALYPSE OF ABRAHAM ANDREI A. ORLOV Downloaded from Cambridge Books Online by IP 130.209.6.50 on Thu Aug 08 23:36:19 WEST 2013. -

Dating the Tower of Babel Events with Reference to Peleg and Joktan

JOURNAL OF CREATION 31(1) 2017 || PAPERS Dating the Tower of Babel events with reference to Peleg and Joktan Andrew Sibley This paper discusses and seeks to identify the date of the Babel event from the writing of biblical and extra-biblical sources. This is a relevant question for creationists because of questions about the timing of post-Flood climatic changes and human migration. Sources used include the Masoretic Text, the Samaritan Pentateuch, the Septuagint, and the Book of Jubilees, and related historical commentaries. Historical sources suggest that the Babel dispersion occurred in the time of Joktan’s extended family and Peleg’s life. The preferred solution of this paper is to follow the Masoretic Text and the Seder Olam Rabbah commentary that places the Babel event 340 years post-Flood at Peleg’s death. Other texts of the Second Temple period vary from this by only three to six decades, which lends some support to the conclusion. his paper seeks to identify the date of the Babel incident “These are the clans of the sons of Noah, according Twith reference to events in the life of Eber’s sons, Peleg to their genealogies, in their nations, and from these and Joktan. Traditionally the Babel event is associated the nations spread abroad on the earth after the flood.” with a division (Genesis 10:25) in the life of Peleg, and this The problem is that even if Joktan was the elder traditional understanding, relating to confusion of languages brother (which is doubtful because the name implies lesser and demographic scattering, is accepted here. -

Israel's Conquest of Canaan: Presidential Address at the Annual Meeting, Dec

Israel's Conquest of Canaan: Presidential Address at the Annual Meeting, Dec. 27, 1912 Author(s): Lewis Bayles Paton Reviewed work(s): Source: Journal of Biblical Literature, Vol. 32, No. 1 (Apr., 1913), pp. 1-53 Published by: The Society of Biblical Literature Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3259319 . Accessed: 09/04/2012 16:53 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The Society of Biblical Literature is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal of Biblical Literature. http://www.jstor.org JOURNAL OF BIBLICAL LITERATURE Volume XXXII Part I 1913 Israel's Conquest of Canaan Presidential Address at the Annual Meeting, Dec. 27, 1912 LEWIS BAYLES PATON HARTFORD THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY problem of Old Testament history is more fundamental NO than that of the manner in which the conquest of Canaan was effected by the Hebrew tribes. If they came unitedly, there is a possibility that they were united in the desert and in Egypt. If their invasions were separated by wide intervals of time, there is no probability that they were united in their earlier history. Our estimate of the Patriarchal and the Mosaic traditions is thus conditioned upon the answer that we give to this question. -

Bible Reading & Questions for April

Bible Reading & Questions for April 2-8 April 2 → Read Genesis 10-12 1) Who was the father of all the children of Eber?_____________________________________________________. 2) At what place did the LORD confound the language of all the earth?____________________________________. 3) How old was Terah when he died?_______________________________________________________________. 4) Whose house did the LORD plague because of Sarai? _______________________________________________. April 3 → Read Genesis 13-16 1) What city's men are described as being “wicked and sinners before the LORD exceedingly?” ________________ ___________________________________________________________________________________________. 2) How many trained servants born in his own house did Abram take with him to rescue Lot? __________________ ___________________________________________________________________________________________. 3) What river is referred to as “the great river?”_______________________________________________________. 4) In what “way” was the fountain of water where the angel of the LORD found Hagar located? ________________ ___________________________________________________________________________________________. April 4 → Read Genesis 17-19 1) How many princes did the LORD tell Abraham that Ishmael would beget?_______________________________. 2) How many measures of fine meal did Sarah use to make cakes upon the hearth?___________________________. 3) How many angels came to Lot at even (evening)?___________________________________________________. -

A Historical Reading of Genesis 11:1–9: the Sumerian Demise and Dispersion Under the Ur Iii Dynasty

JETS 50/4 (December 2007) 693–714 A HISTORICAL READING OF GENESIS 11:1–9: THE SUMERIAN DEMISE AND DISPERSION UNDER THE UR III DYNASTY paul t. penley* i. available options for reading genesis 11:1–9 Three options are available for approaching the question of historicity in Gen 11:1–9: ahistorical primeval event; agnostic historical event; and known historical event. A brief survey of each approach will provide the initial im- petus for pursuing a reading of this pericope as known historical event, and the textual and archaeological evidence considered in the remainder of this article will ultimately identify this known historical event as the demise and dispersion of the last great Sumerian dynasty centered at Ur. 1. Ahistorical primeval event. Robert Davidson in his commentary on the neb text of Genesis 1–11 asserts, “It is only when we come to the story of Abraham in chapter 12 that we can claim with any certainty to be in touch with traditions which reflect something of the historical memory of the Hebrew people.”1 Davidson’s opinion reflects the approach to Genesis 1–11 where the narratives are couched in the guise of primeval events that do not correlate to actual history. Westermann also exemplifies this approach when he opts for reading Gen 11:1–9 through the lens of inaccessible primeval event. Even though he acknowledges that the mention of the historical Babylon “is more in accord with the historical etiologies in which the name of a place is often explained by a historical event,” he hypothesizes that “such an element shows that there are different stages in the growth of 11:1–9.”2 Speiser could also be placed in this category on account of the fact that he proposes pure literary dependence on tablet VI of the Enuma Elish.3 In his estimation the narrative is a reformulated Babylonian tradition and questions of historicity are therefore irrelevant.