The Hebrew Revolution and the Revolution of the Hebrew Language Between the 1880S and the 1930S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1) Meeting Your Bible 2) Discussing the Bible (Breakout Rooms for 10

Wednesday Wellspring: A Bible Study for UU’s (part 1) Bible Study 101: Valuable Information for Serious Students taught by Keith Atwater, American River College worksheet / discussion topics / study guide 1) Meeting Your Bible What is your Bible’s full title, publisher, & publication date? Where did you get your Bible? (source, price, etc.) What’s your Bible like? (leather cover, paperback, old, new, etc.) Any Gospels words in red? What translation is it? (King James, New American Standard, Living Bible, New International, etc.) Does your Bible include Apocrypha?( Ezra, Tobit, Maccabees, Baruch) Preface? Study Aids? What are most common names for God used in your edition? (Lord, Jehovah, Yahweh, God) The Bible in your hands, in book form, with book titles, chapter and verse numbers, page numbers, in a language you can read, at a reasonably affordable price, is a relatively recent development (starting @ 1600’s). A Bible with cross-references, study aids, footnotes, commentary, maps, etc. is probably less than 50 years old! Early Hebrew (Jewish) Bible ‘books’ (what Christians call the Old Testament) were on 20 - 30 foot long scrolls and lacked not only page numbers & chapter indications but also had no punctuation, vowels, and spaces between words! The most popular Hebrew (Jewish) Bible @ the time of Jesus was the “Septuagint” – a Greek translation. Remember Alexander the Great conquered the Middle East and elsewhere an “Hellenized’ the ‘Western world.’ 2) Discussing the Bible (breakout rooms for 10 minutes. Choose among these questions; each person shares 1. Okay one bullet point to be discussed, but please let everyone say something!) • What are your past experiences with the Bible? (e.g. -

Migration of Jews to Palestine in the 20Th Century

Name Date Migration of Jews to Palestine in the 20th Century Read the text below. The Jewish people historically defined themselves as the Jewish Diaspora, a group of people living in exile. Their traditional homeland was Palestine, a geographic region on the eastern coast of the Mediterranean Sea. Jewish leaders trace the source of the Jewish Diaspora to the Roman occupation of Palestine (then called Judea) in the 1st century CE. Fleeing the occupation, most Jews immigrated to Europe. Over the centuries, Jews began to slowly immigrate back to Palestine. Beginning in the 1200s, Jewish people were expelled from England, France, and central Europe. Most resettled in Russia and Eastern Europe, mainly Poland. A small population, however, immigrated to Palestine. In 1492, when King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella expelled all Jewish people living in Spain, some refugees settled in Palestine. At the turn of the 20th century, European Jews were migrating to Palestine in large numbers, fleeing religious persecution. In Russia, Jewish people were segregated into an area along the country’s western border, called the Pale of Settlement. In 1881, Russians began mass killings of Jews. The mass killings, called pogroms, caused many Jews to flee Russia and settle in Palestine. Prejudice against Jews, called anti-Semitism, was very strong in Germany, Austria-Hungary, and France. In 1894, a French army officer named Alfred Dreyfus was falsely accused of treason against the French government. Dreyfus, who was Jewish, was imprisoned for five years and tried again even after new information proved his innocence. The incident, called The Dreyfus Affair, exposed widespread anti-Semitism in Western Europe. -

Tanakh Versus Old Testament

Tanakh versus Old Testament What is the Tanakh? The Tanakh (also known as the Hebrew Bible) was originally written in Hebrew with a few passages in Aramaic. The Tanakh is divided into three sections – Torah (Five Books of Moshe), Nevi’im (Prophets), and Ketuvim (Writings). The Torah is made up of five books that were given to Moshe directly from God after the Exodus from Mitzrayim. The Torah was handed down through the successive generations from the time of Moshe. The Torah includes the creation of the earth and the first humans, the Great Flood and the covenant with the gentiles, the Hebrew enslavement and Exodus of the Hebrews from Mitzrayim, giving of the Torah, renewal of Covenant given to Avraham, establishment of the festivals, wandering through the desert, the Mishkan, Ark, and Priestly duties, and the death of Moshe. The Nevi’im covers the time period from the death of Moshe through the Babylonian exile and contains 19 books. The Nevi’im includes the time of the Hebrews entering Eretz Yisrael, the conquest of Yericho, the conquest of Eretz Yisrael and its division among the tribes, the judicial system, Era of Shaul and David, Shlomo’s wisdom and the construction of the First Beit HaMikdash, kings of Yisrael and Yehuda, prophecy, messianic prophecies, and the Babylonian exile. The Ketuvim covers the period after the return from the Babylonian exile and contains 11 books. The Ketuvim is made up of various writings that do not have an overall theme. This section of the Tanakh includes poems and songs, the stories of Iyov, Rut, and Ester, the writings and prophecies of Dani’el, and the history of the kings of Yisrael and Yehuda. -

2 the Assyrian Empire, the Conquest of Israel, and the Colonization of Judah 37 I

ISRAEL AND EMPIRE ii ISRAEL AND EMPIRE A Postcolonial History of Israel and Early Judaism Leo G. Perdue and Warren Carter Edited by Coleman A. Baker LONDON • NEW DELHI • NEW YORK • SYDNEY 1 Bloomsbury T&T Clark An imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc Imprint previously known as T&T Clark 50 Bedford Square 1385 Broadway London New York WC1B 3DP NY 10018 UK USA www.bloomsbury.com Bloomsbury, T&T Clark and the Diana logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc First published 2015 © Leo G. Perdue, Warren Carter and Coleman A. Baker, 2015 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publishers. Leo G. Perdue, Warren Carter and Coleman A. Baker have asserted their rights under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as Authors of this work. No responsibility for loss caused to any individual or organization acting on or refraining from action as a result of the material in this publication can be accepted by Bloomsbury or the authors. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN: HB: 978-0-56705-409-8 PB: 978-0-56724-328-7 ePDF: 978-0-56728-051-0 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. Typeset by Forthcoming Publications (www.forthpub.com) 1 Contents Abbreviations vii Preface ix Introduction: Empires, Colonies, and Postcolonial Interpretation 1 I. -

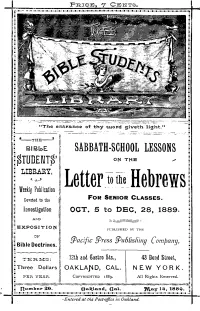

Letter to the Hebrews

7 CLI-rs. 11,1•. 1 •112,12 . 1 •.•.i.M.1211•11.1112 .11111 •11•11 •11. 411•11 .11•11•11 .1 .1.11 •11 •11211.1.11•11.1121.•.•111.11•11......111....... "The entrance of thy word giveth light." BIBLDE SABBATH-SCHOOL LESSONS TUDENTS' TtlE LIBRARY, o the weekti Publication I Letter t Hebrews Devoted to the FOR SENIOR CLASSES. Investigation :3 OCT. 5 to DEC, 28, 1889. AND 1 EXPOSITION PUBLISHED IsY THE OF .acific gress guNishinll Company, :Bible Doctrines. 12th and eastro Sts., 43 Bond Street, :Three Dollars OAKLAJ1D, CAL. NEW YORK. • PER YEAR. • COPYRIGHTED 1889. All Rights Reserved. • number 20. Oakland, Gal. 2otay 114, 1889. : ▪ •„. ,.1•11•11. •11•11..1•11•11.11.112 1 .11 2 11 •11.11.11•11•11•11.11•11•11•11.11•11•11•11.111. taii•rin .112 -Entered at the Post-office in Oakland. • T H BIBLE STUDENTS' UNARY. The Following Numbers are now Ready, and will be Sent Post-paid on Receipt of Price: No. r. Bible Sanctification. Price, zo cents. No. 2. Abiding Sabbath and Lord's Day. Price, 20 cents. No. 3. Views of National Reform, Series I. Price, 15 cents. No. g. The Saints' Inheritance. Price, zo cents. No. S. The Judgment. Price, 2 cents. No. 6. The Third Angel's Message. Price, ¢ cents. No. 7. The Definite Seventh Day. Price, 2 cents. No. 8. S. S. Lessons: Subject, Tithes and Offerings. Price, 5 cents. No. 9. The Origin and Growth. of Sunday Observance. Price, zo cents. No. iv. -

1. from Ur to Canaan

Copyrighted Material 1. FromUrtoCanaan A WANDERINg PEOPLE In the beginning there were wanderings. The first human -be ings, Adam and Eve, are banished from Gan Eden, from Paradise. The founder of monotheism, Abraham, follows God’s com- mand, “Lech lecha” (“Go forth”), and takes to wandering from his home, Ur in Mesopotamia, eventually reaching the land of Canaan, whence his great-grandson Joseph will, in turn, depart for Egypt. Many generations later Moses leads the Jews back to the homeland granted them, which henceforth will be given the name “Israel,” the second name of Abraham’s grandson Jacob. So at least we are told in the Hebrew Bible, certainly the most successful and undoubtedly the most influential book in world literature. Its success story is all the more astonishing when one considers that this document was not composed by one of the powerful nations of antiquity, such as the Egyptians or Assyr- ians, the Persians or Babylonians, the Greeks or Romans, but by a tiny nation that at various times in the course of its history was dominated by all of the above-mentioned peoples. And yet it was precisely this legacy of the Jews that, with the spread of Christianity and Islam, became the foundation for the literary and religious inheritance of the greater part of humanity. By Copyrighted Material 2 C H A P T E R 1 this means, too, the legendary origins of the Jews told in the Bible attained worldwide renown. The Hebrew Bible, which would later be called the Old Testament in Christian parlance, contains legislative precepts, wisdom literature, moral homilies, love songs, and mystical vi- sions, but it also has books meant to instruct us about historical events. -

The Sephardim of the United States: an Exploratory Study

The Sephardim of the United States: An Exploratory Study by MARC D. ANGEL WESTERN AND LEVANTINE SEPHARDIM • EARLY AMERICAN SETTLEMENT • DEVELOPMENT OF AMERICAN COMMUNITY • IMMIGRATION FROM LEVANT • JUDEO-SPANISH COMMUNITY • JUDEO-GREEK COMMUNITY • JUDEO-ARABIC COMMUNITY • SURVEY OF AMERICAN SEPHARDIM • BIRTHRATE • ECO- NOMIC STATUS • SECULAR AND RELIGIOUS EDUCATION • HISPANIC CHARACTER • SEPHARDI-ASHKENAZI INTERMARRIAGE • COMPARISON OF FOUR COMMUNITIES INTRODUCTION IN ITS MOST LITERAL SENSE the term Sephardi refers to Jews of Iberian origin. Sepharad is the Hebrew word for Spain. However, the term has generally come to include almost any Jew who is not Ashkenazi, who does not have a German- or Yiddish-language background.1 Although there are wide cultural divergences within the Note: It was necessary to consult many unpublished sources for this pioneering study. I am especially grateful to the Trustees of Congregation Shearith Israel, the Spanish and Portuguese Synagogue in New York City, for permitting me to use minutes of meetings, letters, and other unpublished materials. I am also indebted to the Synagogue's Sisterhood for making available its minutes. I wish to express my profound appreciation to Professor Nathan Goldberg of Yeshiva University for his guidance throughout every phase of this study. My special thanks go also to Messrs. Edgar J. Nathan 3rd, Joseph Papo, and Victor Tarry for reading the historical part of this essay and offering valuable suggestions and corrections, and to my wife for her excellent cooperation and assistance. Cecil Roth, "On Sephardi Jewry," Kol Sepharad, September-October 1966, pp. 2-6; Solomon Sassoon, "The Spiritual Heritage of the Sephardim," in Richard Barnett, ed., The Sephardi Heritage (New York, 1971), pp. -

ELIZABETH E. IMBER Clark University (508) 793-7254 Department Of

ELIZABETH E. IMBER Clark University (508) 793-7254 Department of History [email protected] 950 Main Street Worcester, MA 01610 PROFESSIONAL APPOINTMENTS Clark University, Worcester, MA August 2019- Assistant Professor of History, Michael and Lisa Leffell Chair in Modern Jewish History The College of Idaho, Caldwell, ID 2018-2019 Assistant Professor of History, Howard Berger-Ray Neilsen Endowed Chair of Judaic Studies EDUCATION Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD 2018 Ph.D., History Dissertation: “Jewish Political Lives in the British Empire: Zionism, Nationalism, and Imperialism in Palestine, India, and South Africa, 1917-1939” Advisors: Kenneth B. Moss and Judith R. Walkowitz 2013 M.A., History Brandeis University, Waltham, MA 2010 M.A., Near Eastern & Judaic Studies Advisor: Antony Polonsky 2009 B.A., Near Eastern & Judaic Studies and Sociology Magna cum laude with Highest Honors in Near Eastern & Judaic Studies Advisor: Jonathan Sarna University of Edinburgh, Scotland Spring 2008 Visiting Student BOOK Empire of Uncertainty: Jews, Zionism, and British Imperialism in the Age of Nationalism, 1917-1948 (book manuscript in progress) PEER-REVIEWED ARTICLES Elizabeth E. Imber, Curriculum Vitae 2 “Thinking through Empire: Interwar Zionism, British Imperialism, and the Future of the Jewish National Home,” Israel 27-28 (2021): 51-70. [Hebrew] “A Late Imperial Elite Jewish Politics: Baghdadi Jews in British India and the Political Horizons of Empire and Nation,” Jewish Social Studies 23, no. 2 (February 2018): 48-85 BOOK REVIEWS 2020 Partitions: A Transnational History of Twentieth-Century Territorial Separatism, Arie M. Dubnov and Laura Robson, eds. Journal of Israeli History (forthcoming) 2018 Christian and Jewish Women in Britain, 1880-1940: Living with Difference, Anne Summers. -

Apples from the Desert”: Form and Content

Advances in Social Sciences Research Journal – Vol.4, No.6 Publication Date: March 25, 2017 DoI:10.14738/assrj.46.2908. Kizel, T. (2017). Image of the Religious Jewish Woman in Savyon Liebrecht’s Story “Apples from the Desert”: Form and Content. Advances in Social Sciences Research Journal, 4(6) 60-72 Image of the Religious Jewish Woman in Savyon Liebrecht’s Story “Apples from the Desert”: Form and Content Dr. Thaier Kizel Head of the Department of Hebrew Language and Hebrew Literature Arab Academic College of Education, Haif INTRODUCTION Divine missions have always been associated with men. Men were entrusted by God to worship Him and women were men’s helpers in the dissemination of the message, although usually their role was restricted to hearth and home. In modern times women began to share men’s roles in every aspect of life, in religion, in politics and in society. In fact, women in some cases have pushed men out of some of the latter’s former roles in life. The afore-mentioned facts are also applicable to Judaism, whose founding prophet Moses was a man. Jewish women obeyed the ritual law because of the men. However, as just noted, their role was purely domestic. However, they began to rebel in every domain, including that of religion, even after they immigrated to Israel. The Jewish religion played an important role in defining the place of women in every aspect of Jewish life, whether in politics, society, religion or any other. Their role at first was marginal, in fact practically non-existent, at the birth of modern Hebrew literature and the emergence of the Zionist movement. -

The Patriotism Education in History Courses of Israeli Middle School

Asian Journal of Middle Eastern and Islamic Studies ISSN: (Print) (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rmei20 The Patriotism Education in History Courses of Israeli Middle School Yi Li To cite this article: Yi Li (2021): The Patriotism Education in History Courses of Israeli Middle School, Asian Journal of Middle Eastern and Islamic Studies, DOI: 10.1080/25765949.2021.1928414 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/25765949.2021.1928414 Published online: 04 Jun 2021. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 11 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rmei20 ASIAN JOURNAL OF MIDDLE EASTERN AND ISLAMIC STUDIES https://doi.org/10.1080/25765949.2021.1928414 RESEARCH ARTICLE The Patriotism Education in History Courses of Israeli Middle School Yi Li Middle East Studies Institute of Shanghai International Studies University, China ABSTRACT KEYWORDS Promoting patriotism and national cohesion in history classes is a Israel; middle school; well-known practice in modern countries, and especially evident history educa- in countries embroiled in ongoing conflicts. Patriotism in middle tion; Patriotism school history education of Israel bear the task to inherit the essence of Jewish traditional culture, promote awakening civic consciousness and teach the history of nation building. The courses contains main lines of national image creation, complaints for diaspora history, reflection on the holocaust, the current situ- ation of the stalemate with rivalry countries and the outlook for the trend towards integration. It aims at shaping the minds of nation residents with different ethnic, religious, cultural and polit- ical background, and turn them into social members with a strong sense of responsibility, characteristics of multicultural and harmonious coexistence. -

Tamar Amar-Dahl Zionist Israel and the Question of Palestine

Tamar Amar-Dahl Zionist Israel and the Question of Palestine Tamar Amar-Dahl Zionist Israel and the Question of Palestine Jewish Statehood and the History of the Middle East Conflict First edition published by Ferdinand Schöningh GmbH & Co. KG in 2012: Das zionistische Israel. Jüdischer Nationalismus und die Geschichte des Nahostkonflikts An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libra- ries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high quality books Open Access. More information about the initiative can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 License. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/. ISBN 978-3-11-049663-5 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-049880-6 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-049564-5 ISBN 978-3-11-021808-4 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-021809-1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-021806-2 A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress. ISSN 0179-0986 e-ISSN 0179-3256 Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliographie; detailed bibliographic data are available in the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 License, © 2017 Tamar Amar-Dahl, published by Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston as of February 23, 2017. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/. -

Abraham•S Children in the Genome Era: Major Jewish Diaspora

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector ARTICLE Abraham’s Children in the Genome Era: Major Jewish Diaspora Populations Comprise Distinct Genetic Clusters with Shared Middle Eastern Ancestry Gil Atzmon,1,2,6 Li Hao,3,6,7 Itsik Pe’er,4,6 Christopher Velez,3 Alexander Pearlman,3 Pier Francesco Palamara,4 Bernice Morrow,2 Eitan Friedman,5 Carole Oddoux,3 Edward Burns,1 and Harry Ostrer3,* For more than a century, Jews and non-Jews alike have tried to define the relatedness of contemporary Jewish people. Previous genetic studies of blood group and serum markers suggested that Jewish groups had Middle Eastern origin with greater genetic similarity between paired Jewish populations. However, these and successor studies of monoallelic Y chromosomal and mitochondrial genetic markers did not resolve the issues of within and between-group Jewish genetic identity. Here, genome-wide analysis of seven Jewish groups (Iranian, Iraqi, Syrian, Italian, Turkish, Greek, and Ashkenazi) and comparison with non-Jewish groups demonstrated distinctive Jewish population clusters, each with shared Middle Eastern ancestry, proximity to contemporary Middle Eastern populations, and variable degrees of European and North African admixture. Two major groups were identified by principal component, phylogenetic, and identity by descent (IBD) analysis: Middle Eastern Jews and European/Syrian Jews. The IBD segment sharing and the proximity of European Jews to each other and to southern European populations suggested similar origins for European Jewry and refuted large-scale genetic contributions of Central and Eastern European and Slavic populations to the formation of Ashkenazi Jewry.