Notes on Cruck Creation Page1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BRANDON HILL TREE TRAIL Explore the Trees, Both Rare and Native, with This Specially Designed Tree Trail

Getting there BRANDON HILL TREE TRAIL Explore the trees, both rare and native, with this specially designed tree trail • The hill has historically been used for grazing and generally been without many trees except hawthorn and oak. • Now it has one of the best collections of trees in the city with just under 500 trees on the hill covering nearly 100 different species. • If you would like help to identify other trees on the hill such as box elder, maple, tulip, wild service, turkey oak and the many fruit trees in the orchard area the Bristol City Council ‘Know Your Place’ website maps all the trees at http://tinyurl.com/brandonkyp Brandon Hill is located just off Park Street in Bristol City Centre. • If you get a chance once you’ve finished take the time to There are many buses that go by, including services from Temple climb to the top of Cabot Tower to get a birds eye view of Meads Train Station (www.firstgroup.com). There is a bicycle rank the trees on the trail. at the Park Street end of both Charlotte Street and Great George Street. Two NCP car parks are within easy walking distance as well • We hope you will return in other seasons to appreciate the as many parking meters in the immediate vicinity. continually changing features of the trees. The area is well served with food shops, so why not take a picnic, but please dispose of your waste in the bins provided. How the Wellingtonia will look when fully mature in relation to Cabot Tower Postcode: BS1 5QB Grid Reference: ST580729 The Wellingtonia (Tree Trail no. -

Timber in Architecture Supplement CONTENTS

TIMBER IN adf ARCHITECTURE 10.16 A great deal BETTER than ply Join in the conversation, #SterlingOSB @Sterling_OSB SterlingOSB 10.16 Timber in architecture supplement CONTENTS 4 Industry news and comment PROJECTS 15 French resistance to concrete A CLT office building currently on site in Paris is set to become an emblem of timber construction in France, as the country’s largest building of its kind. Jess Unwin speaks to its architects about how modern engineered timber is gaining traction as a solution 21 Timber transformation Cross-laminated timber provided an ingenious structural solution as well as a crisp-lined urban aesthetic for the refurbishment and extension of 142 Bermondsey Street in Central London. Stephen Cousins reports 27 Winners in wood design The winners of the 45th annual Wood Awards will be revealed in November. Ahead of the ceremony, Sarah Johnson exclusively previews the 27 shortlisted projects in the Buildings Competition section FEATURES 33 Oriented towards design Stuart Devoil of Smartply explains how the humble sheet of OSB has become a design solution as engineered timber panels are being used across the building sector, from the construction of energy efficient and low carbon homes to site hoardings and everything in between 35 Stamping out fire risk Dire consequences await designers and construction firms if fire retardant treatments fail to perform during a blaze. Mike Smith of Lonza outlines how to ensure your protected timbers are compliant 38 38 Why a wood first policy stacks up Greg Cooper of B & K Structures -

Printable Intro (PDF)

round wood timber framing make an A shape. They can still be found in old barns and cottages. But they had to find very long pieces of wood, so people started making small squares and building them up to the right shape, then joining the squares diagonally to make a roof. By now, everyone was squaring their timber, because a) it's more uniform, and removes uncertaintly; b) all joints can be almost identical – you don't have to take into consideration the shape of the tree; unskilled people can then be employed to make standard joints; and c) right- angles fit better, joints become stronger, and you can fit bricks / wattle & daub in more easily. Everything is flat and flush. what are the benefits? So round wood could be considered old- fashioned, but the reasons for resurrecting it are aesthetic and ecological. It looks pretty; it's a Hammering a peg into a round wood joint with a natural antidote to the square, flat, generic world home-made wooden mallet. that we build; it reconnects people with the forms of the natural world that are more relaxing to the eye; and it reminds us that wood comes from what is it? trees. Also, you can use coppiced wood and Round wood is straight from the tree (with or smaller dimension timber. If you use squared without bark), without any processing, squaring or wood, you need to cut down mature trees and re- planking. Timber framing is creating the structural plant, but a coppiced tree continually re-grows. framework for a building from wood. -

International Auction Gallery 1580 S

International Auction Gallery 1580 S. Sinclair St., Anaheim, CA 92806 714-935-9294 July 8, 2013 Auction Catalog Prev. @Sun. (7/7) 10am-4pm & Mon. from 10am, Sale Starts 4pm 1 Bar light with tall ship on porcelain stein 2 3 Haviland plates, 3 Haviland saucers, 2 sets cups and saucer, and a signed R.S. Prussia porcelain plate painted with 3 7 hat pins 4 Amber style snuff bottle 5 Copper and glass wall light and milk glass globe ceiling light 6 2 pre-Columbian style pottery figures 7 7pc 50's dinette set (as is) 8 Antique Japanese Satsuma vase (rim repair) 9 Chinese famille noir wine jar painted with butterflies with handle in monkey motif 10 Carved stone plaque with copper shield, possibly American Indian 11 Carved wood framed mirror 11A 2 wood framed mirror and a mosaic panel 11B 7 paintings and prints 11C 2 signed lithograph 11D Oriental motif watercolor and a Chinese figure collage 12 A fine antique wood carved storage box 13 2pc India embroidery wall hangings 14 Gilt metal wall light 15 Antique South Asia wood carved building ornament in beast motif 16 lot of misc. pottery and porcelain pieces, and wood carved pieces, some are antique 17 2 antique copper trays and an antique cookie mold 18 Lot of copper and silverplate items 19 Lot of Christmas figures, an inlaid box and pair wood carved panels depicting central American figures 20 Lot of misc. Asian items 21 Lot of figures, glass, and a large wood carved box 22 3 Chinese figures under glass dome 22A Decorative Japanese sword 22B A Forged sword (long knife) 22C A glass pepper shaker with sterling overlay 22D 5 floor lamps, some are antique 23 2 signed etching depicting abstract subjects, signed with name and Taxco location 24 Color etching "abstract", signed, dated 1959, and ed. -

Traditional Timber Framing COMMONWEALTH of AUSTRALIA Copyright Regulations 1969

ABPL90085 CULTURE OF BUILDING traditional timber framing COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA Copyright Regulations 1969 Warning This material has been reproduced and communicated to you by or on behalf of the University of Melbourne pursuant to Part VB of the Copyright Act 1968 (the Act). The material in this communication may be subject to copyright under the Act. Any further copying or communication of this material by you may be the subject of copyright protection under the Act. do not remove this notice CARPENTRY AND THE MORTICE & TENON grooved stone axe head from Vevey, France Amerindian axe Jean-François Robert, Rêver l’Outil: gestes essentiels – outils de toujours (Éditions Cabédita, La Lêchére [Savoie] 1995), p 91 stone axe in a wooden haft, earlier Neolithic, about 3700-3100 BC, Ehenside Tarn, Cumbria, England. British Museum PE POA 109.6, 190.7 Miles Lewis Egyptian adze, 18th Dynasty, reign of Hatshepsut, c 1673-58 BC British Museum EA 26279 J H Taylor [ed], Journey through the Afterlife: Ancient Egyptian Book of the Dead (British Museum Press, London 2010), p 99 Egyptian carpenter’s tools Lewis, Architectura, p 53 Egyptian maul & adze carpenter on a scaffold, using an adze Rose-Marie & Rainer Hagen, Egypt: People, Gods, Paroahs (Taschen, Koln & London 1999), p 82, 83 Egypt: model carpenter's shop, including a carpenter cutting a tenon joint in a plank Egyptian Museum, Cairo, JE 46722 Miles Lewis detail of the Egyptian carpenter’s shop. Lewis, Architectura, p 132 fresco of an Egyptian carpenter using a saw Hagen, Egypt, p 72 mortice and -

Green Oak in Construction

Green oak in construction Green oak in construction by Peter Ross, ARUP Christopher Mettem, TRADA Technology Andrew Holloway, The Green Oak Carpentry Company 2007 TRADA Technology Ltd Chiltern House Stocking Lane Hughenden Valley High Wycombe Buckinghamshire HP14 4ND t: +44 (0)1494 569600 f: +44 (0)1494 565487 e: [email protected] w: www.trada.co.uk Green oak in construction First published in Great Britain by TRADA Technology Ltd. 2007 Copyright of the contents of this document is owned by TRADA Technology Ltd, Ove Arup and Partners (International) Ltd, and The Green Oak Carpentry Company Ltd. © 2007 TRADA Technology Ltd, Ove Arup and Partners (International) Ltd, and The Green Oak Carpentry Company Ltd. All rights reserved. No copying or reproduction of the contents is permitted without the consent of TRADA Technology Ltd. ISBN 978-1900510-45-5 TRADA Technology and the Consortium of authoring organisations wish to thank the Forestry Commission, in partnership with Scottish Enterprise, for their support in the preparation of this book. The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the Forestry Commission or Scottish Enterprise. Building work involving green oak must comply with the relevant national Building Regulations and Standards. Whilst every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of the advice given, the Publisher and the Authors, the Forestry Commission and Scottish Enterprise cannot accept liability for loss or damage arising from the information supplied. The assistance of Patrick Hislop, BA (Hons), RIBA, consultant architect, TRADA Technology Ltd as specialist contributor is also acknowledged. -

A Cruck House at Lower Radley, Berks

A Cruck House at Lower Radley, Berks. By DAVID A. HINTON INTRODUCTIO" ADLEY is a Thames·side parish, between Oxford and Abingdon, on the R Berk hire bank. Between the modern railway line and the river, is a small hamlet known as Lower Radley, standing some 175 ft. abo"e sea-level, and about quarter of a mile from the river. It is composed of houses dating from the 14th to the 19th centuries, built on both sides of a lane which runs round a rectangular field 350 yards long, and 250 yards wide. When one of these houses Grid Reference SU532990) was condemned, the owner, Mrs. F. B. Levetus, who lives in Lower Radley, very kindly allowed a complete archaeo logical examination to take place.' The house was" cruck-built, thatched dwelling, approximately 46 ft. 6 ins. 16 ft. 6 ins. 'sec Ground Plan, FIG. 5. Only the west cruck Cruck I) was visible from the exterior, for the eastern gable had a lean-to shed attached to it. Otherwise, there was nothing to suggest a pre-Tudor date, for the timber framing was covered by lath and plaster, and much of the front had been rebuilt in brick. Inside, however, four more crucks were found, the building being divided into four rooms upstairs and down. The partitions came at the erucks, except at one point downstairs, where the dividing wall between the second and third bays was about 3 ft. to the west of the central cruck Cruck II I . It was decided that so far as safety permitted and at times rather further), we should gradually remO,'e aU the additions to the original building, so that the skeleton of a Medieval house would remain. -

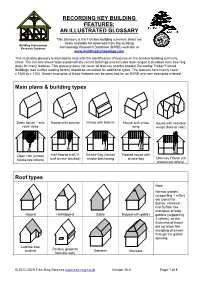

Recording Key Building Features: an Illustrated Glossary

RECORDING KEY BUILDING FEATURES: AN ILLUSTRATED GLOSSARY This Glossary & the Tick-box building summary sheet are freely available for download from the Building Building Archaeology Research Database Archaeology Research Database (BARD) web-site at www.buildingarchaeology.com This illustrated glossary is intended to help with the identification of features on the tick-box building summary sheet. The tick-box sheet helps systematically record buildings and includes date ranges (calculated from tree-ring data) for many features. This glossary does not cover all features and the booklet Recording Timber Framed Buildings (see further reading below) should be consulted for additional types. The features here mainly cover c.1400 to c.1700. Known examples of these features can be searched for on BARD and new examples entered. Main plans & building types Basic house – one House with outshot House with lean-to House with cross House with two face room deep wing wings (front or rear) Open Hall (smoke Half-floored hall (½ Smoke-Bay (limited Floored house with Chimney House (no blackened rafters) roof smoke blacked) smoke blackening smoke-bay blackened rafters) Roof types Note: Narrow gablets (supporting 1 rafter) are typical for Surrey. However, mid Suffolk has examples of wide Hipped Half-hipped Gable Hipped with gablet gablets (supporting 3 rafters), so the thickness of thatch did not block the escaping of smoke through the gablet opening. Catslide over Pentice (projects outshot Gambrel Mansard from the wall) © 2012-2020 Tree-Ring Services www.tree-ring.co.uk Version 10.0 Page 1 of 8 Roof and Roof Structure Crown post Queen strut (3) King Post Queen Post Scissor brace King strut Crown strut Queen strut (2) Raking Queen strut Fan truss Post & Rafter truss - comprises of principal rafters and wall posts secured by knee braces or sling-braces, but Common rafter roof with only stub - has no purlins or tiebeamn (or none at Curved principal rafters other longitudinal all). -

TRACE 2014) Aviemore, Scotland Tree Rings in Archaeology, Climatology and Ecology6-10 May 2014

Tree Rings in Archaeology, Climatology and Ecology (TRACE 2014) Aviemore, Scotland Tree Rings in Archaeology, Climatology and Ecology6-10 May 2014 TRACE 2014 Aviemore, Scotland 6-10 May 2014 1 Tree Rings in Archaeology, Climatology and Ecology (TRACE 2014) Aviemore, Scotland 6-10 May 2014 We have great pleasure in welcoming you to the 2014 Tree Rings in Archaeology, Climatology and Ecology Conference in Aviemore. It is particularly fitting that TRACE be held here in Scotland, as a significant portion of research has been undertaken on the nearby Rothiemurchus Estate by the University of St Andrews’ Scottish Pine Project (http://www.st- andrews.ac.uk/~rjsw/ScottishPine/) over the past several years. We therefore welcome you to this beautiful area, home to some of the most extensive pristine remnant patches of natural and semi-natural Scots pine woodland in the country. We have an excellent scientific programme to offer you spread across three days, in both oral and poster formats. TRACE 2014 seeks to strengthen the network and scientific exchange of scientists and students involved in the study of tree-rings. It aims at presenting and discussing new discoveries and approaches in wide field of tree-ring science; the scope of the meeting includes all fields of dendrochronology, such as tree-rings in archaeology, climate, geomorphology, glaciology, fire history, forest dynamics, hydrology, physiology, and stable isotopes. This annual meeting has the reputation as a friendly, sociable and intimate gathering that promotes the visibility of postgraduate and early career researchers, and we are looking forward to continuing that tradition. In addition to the scientific programme, we have a conference dinner and ceilidh lined up – hope you brought your kilts and other national costumes! We would like to thank various organisations and companies for their sponsorship of the conference. -

The Cruck-Framed Barn at Seddons Fold, Prestolee

10 THE CRUCK-FRAMED BARN AT SEDDONS FOLD, PRESTOLEE V Tanner INTRODUCTION were undertaken by the Unit in January and February Seddons Fold is situated on an area of land form- ed by a sharp bend in the River Irwell at No documentation for the barn itself has been Prestolee, Bolton (SD 756 062). The barn lies to found, but the Fold was the former home of the the south of a complex of buildings dating from Seddon family, who are known to have held land in several periods. The stone farmhouse was built the area from the late 1 5th century onwards. The during the 16th and 17th centuries, and has an Seddons appear to have had considerable standing in early Georgian extension to the west. Since the the locality, and the size of the barn and the very barn is in poor condition and its future remains in fact that it survives today, probably reflects the doubt, measured drawings and a photographic record extent of their status. The family history is part- icularly well documented by Fletcher (1880). THE BARN The barn is a cruck-framed building, in which the weight of the roof is carried by a series of transverse trusses, formed by pairs of massive cruck blades. They are full crucks, with the timbers rising from ground level to the apex of the roof. Fach truss is also strengthened by cross- beams connecting the two blades (Ryder 1979, 6). These occur in various positions at Seddons Fold: below the apex of the timbers at roof level (the collar-beam); where the cruck trusses are connected by longitudinal timbers supporting the rafters (the purlin-beam); where a transverse beam meets the wall level (the wall tie-beam); and at ground level as a lower cross-beam. -

Read the Review

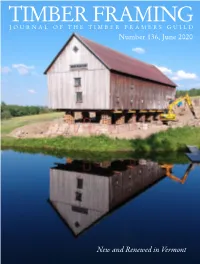

TIMBER FRAMING JOURNAL OF THE TIMBER FRAMERS GUILD Number 136, June 2020 New and Renewed in Vermont TIMBER FRAMING JOURNAL OF THE TIMBER FRAMERS GUILD NUMBER 136 JUNE 2020 CONTENTS BOOK REVIEW: CRUCK BUILDING 2 Jack A. Sobon A HYBRID FRAME IN VERMONT 4 Will Gusakov SAVING A LARGE NEW ENGLAND BARN 8 Eliot Lothrop On the cover, Wolcott, Vermont, barn lifted and shored in place while a new foundation is poured. See article, page 8. Photo: Alex Howe. On the back cover, Bedstone Manor (1448), Shropshire, England. Drawing shows asymmetry common in cruck framing, including molding details. In photo, massive free dovetail linking cruck blade and spur. Drawing and photo: M. Moran (from Cruck Building). Copyright © 2020 Timber Framers Guild 116 Pleasant Street, Suite 334, Easthampton, MA 01027 833-862-7376 | [email protected] Cruck Building Editorial Correspondence Please email [email protected]. Cruck Building: A Survey. Nat Alcock, P. S. Barnwell, and Martin Cherry, editors. Donington, UK: Shaun Tyas, 2019. 7½ in. x 10 in., Editors Michael Cuba, Adam Miller 406 pp. 421 illustrations. Hardcover, £50. Editor Emeritus Kenneth Rower RUCK framing is a historic method of timber building, Contributing Editors found primarily in the British Isles, where the roof is History Jan Lewandoski, Jack A. Sobon supported by pairs of curved or elbowed timbers (called Ben Brungraber, Tom Nehil Ccruck ) rising from the sill and joined at their apex, an early Engineering blades A-frame (Fig. 1). Since I first saw images of cruck frames in the Layout/Design Erin Moore classic book Shelter (Shelter Publications, 1973) back in the ’70s, I have been smitten with their beauty, grace, and charm, constructing Printed on Anthem Plus, an FSC® certified paper my first cruck frame in 1985. -

Traditional Buildings in Ireland Home Owners Handbook Featuring the Mourne Homesteads Experience

Traditional Buildings in Ireland Home Owners Handbook Featuring The Mourne Homesteads Experience Published by: Mourne Heritage Trust Researcher and Writer: Richard Oram Conservation Architect and Writer: Dawson Stelfox Acknowledgements The authors and publishers would like to thank the following organisations and people for their assistance in the production of this publication: Co-operation Ireland EU Programme for Peace and Reconciliation Heritage Lottery Fund Northern Ireland Housing Executive Alastair Coey, Architects Shaffrey Associates, Architects John Harrison Associates, Heritage Development Paul McMahon, Office of Public Works (OPW) Katrina Carlin, Construction Industry Training Board (CITB) Frank Nugent, An Foras Áiseanna Saothair (FÁS) Bairbre ni Fhlionn, Department of Irish Folklore, UCD Harriet Devlin, Conservation Consultant Primrose and Edward Wilson Evelyn Brown, Kilkeel High School Mourne Heritage Trust Built Heritage Working Group ISBN 0 9549510 0 X Design by: Rodney Miller Associates, Belfast Photography: Mourne Heritage Trust, Christopher Hill Photographic, Edgar Brown Photography, Consarc Design Group Printed by: Impro Printing, Belfast First published in 2004 by Mourne Heritage Trust © Text: Mourne Heritage Trust All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the permission of the publishers and copyright owners. Preface The purpose of this