Green Oak in Construction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mechanical Characterization of Traditional Connections in Half-Timbered Walls: Experimental Results and Retrofitting Solutions

Aikaterini Maria Koukouviki Mechanical characterization of traditional connections in half-timbered walls: experimental results and retrofitting solutions Portugal | 2013 Mechanical characterization of traditional connections in half-timbered walls: experimental results and retrofitting solutions DECLARATION Name: Aikaterini Maria Koukouviki Email: [email protected] Title of the Mechanical characterization of traditional connections in half-timbered walls: Msc Dissertation: experimental results and retrofitting solutions Supervisor(s): Graça Vasconcelos, Jorge Branco Year: July 2013 I hereby declare that all information in this document has been obtained and presented in accordance with academic rules and ethical conduct. I also declare that, as required by these rules and conduct, I have fully cited and referenced all material and results that are not original to this work. I hereby declare that the MSc Consortium responsible for the Advanced Masters in Structural Analysis of Monuments and Historical Constructions is allowed to store and make available electronically the present MSc Dissertation. University: University of Minho Date: 24 July 2013 Signature: ___________________________ Erasmus Mundus Programme ADVANCED MASTERS IN STRUCTURAL ANALYSIS OF MONUMENTS AND HISTORICAL CONSTRUCTIONS i Mechanical characterization of traditional connections in half-timbered walls: experimental results and retrofitting solutions Erasmus Mundus Programme ii ADVANCED MASTERS IN STRUCTURAL ANALYSIS OF MONUMENTS AND HISTORICAL CONSTRUCTIONS Mechanical -

Analysis and Strengthening of Carpentry Joints 1. Introduction 2

Generated by Foxit PDF Creator © Foxit Software Branco, J.M., Descamps, T., Analysis and strengthening http://www.foxitsoftware.comof carpentry joints. Construction andFor Buildingevaluation Materials only. (2015), 97: 34–47. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2015.05.089 Analysis and strengthening of carpentry joints Jorge M. Branco Assistant Professor ISISE, Dept. Civil Eng., University of Minho Guimarães, Portugal Thierry Descamps Assistant Professor URBAINE, Dept. Structural Mech. and Civil Eng., University of Mons Mons, Belgium 1. Introduction Joints play a major role in the structural behaviour of old timber frames [1]. Current standards mainly focus on modern dowel-type joints and usually provide little guidance (with the exception of German and Swiss NAs) to designers regarding traditional joints. With few exceptions, see e.g. [2], [3], [4], most of the research undertaken today is mainly focused on the reinforcement of dowel-type connections. When considering old carpentry joints, it is neither realistic nor useful to try to describe the behaviour of each and every type of joint. The discussion here is not an extra attempt to classify or compare joint configurations [5], [6], [7]. Despite the existence of some classification rules which define different types of carpentry joints, their applicability becomes difficult. This is due to the differences in the way joints are fashioned depending, on the geographical location and their age. In view of this, it is mandatory to check the relevance of the calculations as a first step. This first step, to, is mandatory. A limited number of carpentry joints, along with some calculation rules and possible strengthening techniques are presented here. -

International Market Report on Wooden Public Buildings

Sustainable Public Buildings Designed and Constructed in Wood (Pub-Wood) Project number: 2018-1-LT01-KA203-046963 International Market Report on Wooden Public Buildings Riga, 2019 ERASMUS + Action KA2: Cooperation for Innovation and The Exchange of good practices. Strategic Partnerships Sustainable Public Buildings Designed and Constructed in Wood (Pub-Wood) Edited by: Prof. Ineta Geipele (Riga Technical University, Latvia) Assoc. Prof. Dr Linda Kauškale (Riga Technical University, Latvia) Prepared by: Assoc. Prof. Dr Laura Tupenaite (Vilnius Gediminas Technical University, Lithuania) Assoc. Prof. Dr Tomas Gečys (Vilnius Gediminas Technical University, Lithuania) Roger Howard Taylor (VIA University College, Denmark) Ole Thorkilsen (VIA University College, Denmark) Peter Ebbesen (VIA University College, Denmark) Assit. Prof. David Trujillo (Coventry University, UK) Assit. Prof. Carl Mills (Coventry University, UK) Jari Komsi (Häme University of Applied Sciences, Finland) Anssi Knuutila (Häme University of Applied Sciences, Finland) Prof. Ineta Geipele (Riga Technical University, Latvia) Assoc. Prof. Dr Linda Kauškale (Riga Technical University, Latvia) 2 ERASMUS + Action KA2: Cooperation for Innovation and The Exchange of good practices. Strategic Partnerships Sustainable Public Buildings Designed and Constructed in Wood (Pub-Wood) TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................... 5 1. NATIONAL WOODEN/TIMBER BUILDINGS’ MARKET -

Arborite Postforming & General Purpose Laminate

ARBORITE POSTFORMING & GENERAL PURPOSE LAMINATES TECHNICAL DATA Manufacturer Arborite 385 Lafleur, Lasalle (Québec), H8R 3H7 Web site : www.arborite.com - Phone: 1-800-996-0366 Alternate manufacturing facility – Fletcher, NC Product Description Arborite decorative laminates are a high pressure thermoset plastic surfacing material. It consists of multi layers of kraft (core) papers impregnated with phenolic resins, covered by a melamine impregnated decorative surface. These layers are then consolidated into a solid sheet under the effect of high temperature and pressure. 0.045" / 1.14 mm Basic Decorative High Pressure Laminates – for horizontal and vertical applications Arborite decorative laminates are engineered to improve the product life cycle for wear, chemical and stain resistance under normal use and conditions. Available in 3 grades, Arborite laminates offer 4 exceptional performance features, and are available in Arborite’s expressive range of colors. Arborite Flex 4 grades: . 0.025" / (0.63 mm) - Arborite laminate type A3 . 0.034" / (0.86 mm) - Arborite laminate type A4 . 0.045" / (1.14 mm) - Arborite laminate type A5 Usage For all types of flatwork applications: work surfaces, counters, cabinets, furniture, equipment, food service, displays, caseworks, doors, walls, ceilings, window sills and frames, partition systems, enclosures, shelving and trims. suitable for most commercial, institutional and residential applications. Typical uses by grade: A3 (0.025") for light duty applications - most vertical surfaces such as interior doors, cabinet fronts, wall paneling and similar surfaces. A4 (0.034") & A5 (0.045") for heavier duty applications – work surfaces, counters, table tops, cabinets, furniture, wall paneling, doors, window sills and similar surfaces. Arborite Postforming & General Purpose Laminates 1 Revised: September 2015 Arborite – Features . -

BRANDON HILL TREE TRAIL Explore the Trees, Both Rare and Native, with This Specially Designed Tree Trail

Getting there BRANDON HILL TREE TRAIL Explore the trees, both rare and native, with this specially designed tree trail • The hill has historically been used for grazing and generally been without many trees except hawthorn and oak. • Now it has one of the best collections of trees in the city with just under 500 trees on the hill covering nearly 100 different species. • If you would like help to identify other trees on the hill such as box elder, maple, tulip, wild service, turkey oak and the many fruit trees in the orchard area the Bristol City Council ‘Know Your Place’ website maps all the trees at http://tinyurl.com/brandonkyp Brandon Hill is located just off Park Street in Bristol City Centre. • If you get a chance once you’ve finished take the time to There are many buses that go by, including services from Temple climb to the top of Cabot Tower to get a birds eye view of Meads Train Station (www.firstgroup.com). There is a bicycle rank the trees on the trail. at the Park Street end of both Charlotte Street and Great George Street. Two NCP car parks are within easy walking distance as well • We hope you will return in other seasons to appreciate the as many parking meters in the immediate vicinity. continually changing features of the trees. The area is well served with food shops, so why not take a picnic, but please dispose of your waste in the bins provided. How the Wellingtonia will look when fully mature in relation to Cabot Tower Postcode: BS1 5QB Grid Reference: ST580729 The Wellingtonia (Tree Trail no. -

Fasteners Set the Industry's Highest Standards for Design, Ease of Use, and Reliability

Keeping your belt up and running SINCE 1907 HEAVY-DUTY MECHANICAL BELT FASTENING SYSTEMS A comprehensive line of mechanical belt fastening systems and belt conveyor maintenance tools that increase uptime and output. Around the world, the most respected name in belt conveyor solutions is Flexco. YOUR PARTNER IN The reason is simple. Flexco belt splicing products have earned the reputation for unsurpassed quality and performance in the most demanding material handling PRODUCTIVITY applications on earth. Our fasteners set the industry's highest standards for design, ease of use, and reliability. The knowledgeable advice and proven solutions we provide our customers help keep conveyor efficiency high and conveyor operation costs low. QUICK FACTS OVER 100 YEARS OF SUCCESS ABOUT FLEXCO • Flexco is a U.S.-based company and HAS BEEN BUILT has been in the belt industry since 1907. BY FOCUSING ON OUR • We have subsidiary locations in Australia, Chile, China, Germany, India, Mexico, Singapore, South Africa, and CUSTOMERS the United Kingdom to service and support customers in more than 150 countries around the world. We have learned to understand our customers' • We have more than 1800 distributor industries and challenges and to respond to their partners throughout the world—we changing needs. partner with the best distributors in We are constantly driving technology and design and every market we serve around the world to ensure our customers have strive to become the leader in belt conveyor solutions that ready access to our products, services, maximize uptime, productivity, and safety. and expert resources. We value industry relationships and believe that together, with a team of industry experts, our customers will • As a company, we focus on training and development and maintaining a receive greater value. -

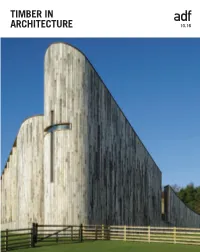

Timber in Architecture Supplement CONTENTS

TIMBER IN adf ARCHITECTURE 10.16 A great deal BETTER than ply Join in the conversation, #SterlingOSB @Sterling_OSB SterlingOSB 10.16 Timber in architecture supplement CONTENTS 4 Industry news and comment PROJECTS 15 French resistance to concrete A CLT office building currently on site in Paris is set to become an emblem of timber construction in France, as the country’s largest building of its kind. Jess Unwin speaks to its architects about how modern engineered timber is gaining traction as a solution 21 Timber transformation Cross-laminated timber provided an ingenious structural solution as well as a crisp-lined urban aesthetic for the refurbishment and extension of 142 Bermondsey Street in Central London. Stephen Cousins reports 27 Winners in wood design The winners of the 45th annual Wood Awards will be revealed in November. Ahead of the ceremony, Sarah Johnson exclusively previews the 27 shortlisted projects in the Buildings Competition section FEATURES 33 Oriented towards design Stuart Devoil of Smartply explains how the humble sheet of OSB has become a design solution as engineered timber panels are being used across the building sector, from the construction of energy efficient and low carbon homes to site hoardings and everything in between 35 Stamping out fire risk Dire consequences await designers and construction firms if fire retardant treatments fail to perform during a blaze. Mike Smith of Lonza outlines how to ensure your protected timbers are compliant 38 38 Why a wood first policy stacks up Greg Cooper of B & K Structures -

Printable Intro (PDF)

round wood timber framing make an A shape. They can still be found in old barns and cottages. But they had to find very long pieces of wood, so people started making small squares and building them up to the right shape, then joining the squares diagonally to make a roof. By now, everyone was squaring their timber, because a) it's more uniform, and removes uncertaintly; b) all joints can be almost identical – you don't have to take into consideration the shape of the tree; unskilled people can then be employed to make standard joints; and c) right- angles fit better, joints become stronger, and you can fit bricks / wattle & daub in more easily. Everything is flat and flush. what are the benefits? So round wood could be considered old- fashioned, but the reasons for resurrecting it are aesthetic and ecological. It looks pretty; it's a Hammering a peg into a round wood joint with a natural antidote to the square, flat, generic world home-made wooden mallet. that we build; it reconnects people with the forms of the natural world that are more relaxing to the eye; and it reminds us that wood comes from what is it? trees. Also, you can use coppiced wood and Round wood is straight from the tree (with or smaller dimension timber. If you use squared without bark), without any processing, squaring or wood, you need to cut down mature trees and re- planking. Timber framing is creating the structural plant, but a coppiced tree continually re-grows. framework for a building from wood. -

International Auction Gallery 1580 S

International Auction Gallery 1580 S. Sinclair St., Anaheim, CA 92806 714-935-9294 July 8, 2013 Auction Catalog Prev. @Sun. (7/7) 10am-4pm & Mon. from 10am, Sale Starts 4pm 1 Bar light with tall ship on porcelain stein 2 3 Haviland plates, 3 Haviland saucers, 2 sets cups and saucer, and a signed R.S. Prussia porcelain plate painted with 3 7 hat pins 4 Amber style snuff bottle 5 Copper and glass wall light and milk glass globe ceiling light 6 2 pre-Columbian style pottery figures 7 7pc 50's dinette set (as is) 8 Antique Japanese Satsuma vase (rim repair) 9 Chinese famille noir wine jar painted with butterflies with handle in monkey motif 10 Carved stone plaque with copper shield, possibly American Indian 11 Carved wood framed mirror 11A 2 wood framed mirror and a mosaic panel 11B 7 paintings and prints 11C 2 signed lithograph 11D Oriental motif watercolor and a Chinese figure collage 12 A fine antique wood carved storage box 13 2pc India embroidery wall hangings 14 Gilt metal wall light 15 Antique South Asia wood carved building ornament in beast motif 16 lot of misc. pottery and porcelain pieces, and wood carved pieces, some are antique 17 2 antique copper trays and an antique cookie mold 18 Lot of copper and silverplate items 19 Lot of Christmas figures, an inlaid box and pair wood carved panels depicting central American figures 20 Lot of misc. Asian items 21 Lot of figures, glass, and a large wood carved box 22 3 Chinese figures under glass dome 22A Decorative Japanese sword 22B A Forged sword (long knife) 22C A glass pepper shaker with sterling overlay 22D 5 floor lamps, some are antique 23 2 signed etching depicting abstract subjects, signed with name and Taxco location 24 Color etching "abstract", signed, dated 1959, and ed. -

Inspection of Wooden Vessels

Guidance on Inspection, Repair, and Maintenance of Wooden Hulls ENCLOSURE (1) TO NVIC 7-95 COMPILED BY THE JOINT INDUSTRY/COAST GUARD WOODEN BOAT INSPECTION WORKING GROUP August 1995 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS A-1 LIST OF FIGURES F-1 GLOSSARY G-1 CHAPTER 1. DESIGN CONSIDERATIONS A. Introduction 1-1 B. Acceptable Classification Society Rules 1-1 C. Good Marine Practice 1-1 CHAPTER 2. PLAN SUBMITTAL GUIDE A. Introduction 2-1 B. Plan Review 2-1 C. Other Classification Society Rules and Standards 2-1 D. The Five Year Rule 2-1 CHAPTER 3. MATERIALS A. Shipbuilding Wood 3-1 B. Bending Woods 3-1 C. Plywood. 3-2 D. Wood Defects 3-3 E. Mechanical Fastenings; Materials 3-3 F. Screw Fastenings 3-4 G. Nail Fastenings 3-5 H. Boat Spikes and Drift Bolts 3-6 I. Bolting Groups 3-7 J. Adhesives 3-7 K. Wood Preservatives 3-8 CHAPTER 4. GUIDE TO INSPECTION A. General 4-1 B. What to Look For 4-1 C. Structural Problems 4-1 D. Condition of Vessel for Inspection 4-1 E. Visual Inspection 4-2 F. Inspection for Decay and Wood Borers 4-2 G. Corrosion & Cathodic Protection 4-6 H. Bonding Systems 4-10 I. Painting Galvanic Cells 4-11 J. Crevice Corrosion 4-12 K. Inspection of Fastenings 4-12 L. Inspection of Caulking 4-13 M. Inspection of Fittings 4-14 N. Hull Damage 4-15 O. Deficiencies 4-15 CHAPTER 5. REPAIRS A. General 5-1 B. Planking Repair and Notes on Joints in Fore and 5-1 Aft Planking C. -

University of Bath

Citation for published version: Harris, R & Roynon, J 2008, 'The Savill Garden Gridshell design and construction' Paper presented at 10th World Conference of Timber Engineering, Miyazaki, Japan, 2/06/08 - 5/06/08, . Publication date: 2008 Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication University of Bath General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 12. May. 2019 The Savill Garden Gridshell Design and Construction Richard HARRIS Professor of Timber Engineering/Technical Director University of Bath / Buro Happold Bath, England Jonathan ROYNON Associate Buro Happold Bath, England Summary The paper describes the design and construction of the roof of the Savill Building. The structure is a timber gridshell, a technique presented at previous WCTE Conferences (2002[1] and 2004[2]). The timber for the Savill Building was harvested from the surrounding woodland. The form of the roof was derived from a simple geometric shape; the analysis and design checks were carried out using the Eurocode. Construction details and process, which developed from the techniques established on earlier buildings, are described. 1. Introduction The first double-layer timber gridshell in the UK, for the Weald and Downland Open Air Museum ( Fig 1) in Sussex, created international interest, quite disproportionate to its size, amongst architects, engineers and carpenters Fig. -

Woodwork Joints: How They Are Set Out, How Made and Where Used

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Woodwork Joints, by William Fairham This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Woodwork Joints How they are Set Out, How Made and Where Used. Author: William Fairham Release Date: May 19, 2007 [EBook #21531] Language: English *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK WOODWORK JOINTS *** Produced by Chris Curnow and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net Transcriber's Note: The Table of Contents has been changed to match the actual chapter headings. A few hyphenations have been changed to make them consistent. Minor typographic errors have been corrected. WOODWORK JOINTS (THE WOODWORKER SERIES) REVISED EDITION WOODWORK JOINTS HOW THEY ARE SET OUT, HOW MADE AND WHERE USED; WITH FOUR HUNDRED ILLUSTRATIONS AND INDEX REVISED EDITION LONDON EVANS BROTHERS, LIMITED MONTAGUE HOUSE, RUSSELL SQUARE, W.C.1 THE WOODWORKER SERIES WOODWORK JOINTS. CABINET CONSTRUCTION. STAINING AND POLISHING. WOODWORK TOOLS. PRACTICAL UPHOLSTERY. WOOD TURNING. WOODCARVING. TIMBERS FOR WOODWORK. FURNITURE REPAIRING AND RE- UPHOLSTERY. HOUSEHOLD REPAIRS AND RENOVATIONS. CARPENTRY FOR BEGINNERS. KITCHEN FURNITURE DESIGNS. BUREAU AND BOOKCASE DESIGNS. LIGHT CARPENTRY DESIGNS. DOORMAKING. EVANS BROTHERS, LIMITED, MONTAGUE HOUSE, RUSSELL SQUARE, LONDON, W.C.1. EDITORIAL FOREWORD To be successful in woodwork construction the possession of two secrets is essential—to know the right joint to use, and to know how to make that joint in the right way.