"The Rise and Fall of Saturn." (PDF)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The $1.5 Billion General Motors Recalls at the Dangerous Intersection of Chapter 11, Article 9, and TARP

University of Cincinnati Law Review Volume 85 Issue 1 Article 4 August 2018 The $1.5 Billion General Motors Recalls at the Dangerous Intersection of Chapter 11, Article 9, and TARP Sally McDonald Henry Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.uc.edu/uclr Recommended Citation Sally McDonald Henry, The $1.5 Billion General Motors Recalls at the Dangerous Intersection of Chapter 11, Article 9, and TARP, 85 U. Cin. L. Rev. (2018) Available at: https://scholarship.law.uc.edu/uclr/vol85/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by University of Cincinnati College of Law Scholarship and Publications. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Cincinnati Law Review by an authorized editor of University of Cincinnati College of Law Scholarship and Publications. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Henry: The $1.5 Billion General Motors Recalls THE $1.5 BILLION GENERAL MOTORS RECALLS AT THE DANGEROUS INTERSECTION OF CHAPTER 11, ARTICLE 9, AND TARP Sally McDonald Henry* I. INTRODUCTION: THE COMPACT VERSION This article discusses how, in the General Motors Corporation (General Motors or GM)1 chapter 11 case, a group of creditors—mostly collateralized loan obligations, hedge funds, pension, and other funds2— (the Funds or the Lenders3) were paid in full, in cash, even though they had no right to the payment, which amounted to almost $1.5 billion. Not only were the Funds paid in full, but in addition, their collateral agent, JPMorgan Chase Bank, N.A. (JPMorgan), is being reimbursed for millions of dollars of legal fees, even though it has no legal right to the reimbursement.4 These improper payments occurred (and continue to occur) even though many other creditors—unsecured bondholders,5 tort creditors, mom and pop business whose existence depend on being paid * Associate Professor, Texas Tech School of Law. -

2009 Saturn Vue Warranty.Pdf

IMPORTANT: This booklet contains important information about the vehicle’s warranty coverage. It also explains owner assistance information and Saturn’s participation in the Mediation/Arbitration Program. Keep this booklet with your vehicle and make it available to a Saturn retailer if warranty work is needed. Be sure to keep it with your vehicle if you sell it so future owners will have the information. Owner’s Name: Street Address: City & State: Vehicle Identification Number (VIN): Date Vehicle First Delivered or Put In Use: Odometer Reading on Date Vehicle First Delivered or Put In Use: © 2008 Saturn Corporation U.S.A. All rights reserved. Printed in U.S.A. GENERAL MOTORS and GM are registered trademarks of General Motors Corporation. SATURN and the SATURN emblems are registered trademarks of Saturn Corporation. Part No. 15898479 B Second Printing 2009 Saturn Limited Warranty and Owner Assistance Information An Important Message to Owners... .....................1 After-Manufacture “Rustproofing” ........................12 Saturn’s Commitment to You ..............................1 Paint, Trim, and Appearance Items ....................12 Owner Assistance .............................................1 Vehicle Operation and Care ..............................13 GM Participation in an Alternative Dispute Maintenance and Warranty Service Records ........13 Resolution Program ........................................1 Chemical Paint Spotting ...................................13 Warranty Service – United States and Canada ......1 Warranty Coverage -

Finding Aid for the Automotive (Non-Ford) Advertisements

Finding Aid for AUTOMOTIVE (NON-FORD) ADVERTISEMENTS COLLECTION, Circa 1900 – Circa 1991 Accession 657 Finding Aid Published: May 2011 20900 Oakwood Boulevard ∙ Dearborn, MI 48124-4088 [email protected] ∙ www.thehenryford.org Automotive (Non-Ford) Advertisements collection Accession 657 OVERVIEW REPOSITORY: Benson Ford Research Center The Henry Ford 20900 Oakwood Blvd Dearborn, MI 48124-4088 www.thehenryford.org [email protected] ACCESSION NUMBER: 657 TITLE: Automotive (Non-Ford) Advertisements collection INCLUSIVE DATES: circa 1900-circa 1991 QUANTITY: 5.6 cubic ft. LANGUAGE: The materials are primarily in English. ABSTRACT: This collection contains advertising tear sheets, advertising proof sheets and advertisements clipped from periodicals on all automotive subjects except those related to Ford Motor Company. Page 2 of 21 Automotive (Non-Ford) Advertisements collection Accession 657 ADMINISTRATIVE INFORMATION ACCESS RESTRICTIONS: The collection is open for research. COPYRIGHT: Copyright for the materials in this collection has not been transferred to The Henry Ford, and may still be held by the respective creator(s). Researchers are responsible for either determining the copyright status of the material or for securing copyright permission. ACQUISITION: Acquired by The Henry Ford from the Ford Motor Company. Acquisition is ongoing. RELATED MATERIAL: Related material held by The Henry Ford: - See Accession 19 for Ford, Lincoln, Mercury, and Edsel advertisements - For subjects other than automotive see the General Advertisement Collection - See Accession 19 for related scrapbooks OTHER FINDING AIDS: Item level catalog records for some of the material can be searched in The Henry Ford collection management system, which is available for researcher use in the Research Center reading room. -

GM 2007 Annual Report

General Motors Corporation 2007 Annual Report next 100 YEARS of leadership. 100 YEARS of innovation. General Motors Corporation 1 100 YEARS of putting people on wheels. 2 General Motors Corporation And we’re just getting started. We’re making the best cars and trucks we ever have. And we’re selling them in more parts of the world than ever before. We’re very proud of our past, but even more excited about our future. We’re focused on what’s next: building the best General Motors yet. General Motors Corporation 3 Bob Lutz Vice Chairman, Global Product Development Fritz Henderson Rick Wagoner GM’s senior leadership in the President & Chairman & Cadillac Display at the 2008 Chief Operating Offi cer Chief Executive Offi cer North American International Auto Show in Detroit, Michigan. 4 General Motors Corporation DEAR STOCKHOLDERS: A century is a long time to be in business. For General Motors, it’s been a century of leadership and achievements, of challenges and opportunities. A centennial is a great time to refl ect on and celebrate the past. But for us, it’s more than that…it’s an oppor- tunity to look forward to our next 100 years. GM’s centennial comes at an exciting time for the 2007 YEAR IN REVIEW auto industry, as we move aggressively to realize the 2007 was another year of important progress for GM, potential of two huge trends that are transforming the as we implemented further signifi cant structural cost global auto industry and society itself. The fi rst trend is reductions in North America, grew aggressively in emerg- the rapidly growing role, and importance, of emerging ing markets, negotiated an historic labor contract with markets. -

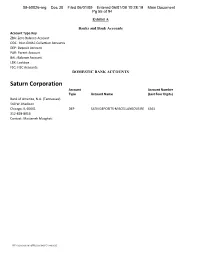

Saturn Corporation Account Account Number Type Account Name (Last Four Digits) Bank of America, N.A

09-50026-reg Doc 30 Filed 06/01/09 Entered 06/01/09 10:28:19 Main Document Pg 55 of 94 Exhibit A Banks and Bank Accounts Account Type Key ZBA: Zero Balance Account ODC : Non GMAC Collection Accounts DEP: Deposit Account PAR: Parent Account BAL: Balance Account LBX: Lockbox FSC: FISC Accounts DOMESTIC BANK ACCOUNTS Saturn Corporation Account Account Number Type Account Name (Last Four Digits) Bank of America, N.A. (Tennessee) 540 W. Madison Chicago, IL 60661 DEP SATN DEPOSITS‐MISCELLANEOUS RE 6363 312‐828‐8016 Contact: Masteneh Masghati NY2:\1985338\20\16JW@20!.DOC\72240.0635 09-50026-reg Doc 30 Filed 06/01/09 Entered 06/01/09 10:28:19 Main Document Pg 56 of 94 Account Type Key ZBA: Zero Balance Account ODC: Non GMAC Collection Accounts DEP: Deposit Account PAR: Parent Account BAL: Balance Account LBX: Lockbox FSC: FISC Accounts Saturn Distribution Corp Account Account Type Account Name Number SATURN DIST Citibank, N.A. (New York) ZBA CORP 1256 388 Greenwich Street 22nd Floor New York NY 10013 212‐816‐2933 Contact: Sarah Terner Chevrolet‐Saturn of Harlem, Inc. Account Account Type Account Name Number Chevrolet‐Saturn JP Morgan Chase PAR of Harlem, Inc. 7901 55 W. 125th Street New York, NY 10027 212‐860‐0261 Contact: Randy Polanco 09-50026-reg Doc 30 Filed 06/01/09 Entered 06/01/09 10:28:19 Main Document Pg 57 of 94 Account Type Key ZBA: Zero Balance Account ODC: Non GMAC Collection Accounts DEP: Deposit Account PAR: Parent Account BAL: Balance Account LBX: Lockbox FSC: FISC Accounts GM Account Type Account Name Account Number Bank of America, N.A. -

From Turnaround to Transformation

General Motors Corporation 2006 Annual Report From turnaround to transformation Contents 3 Letter to Stockholders 44 Management’s Discussion and Analysis 76 Notes to Consolidated Financial Statements 4 Financial Highlights 67 Disclosure Controls and Procedures 125 Selected Financial Data 10 Design Transformation 68 Management’s Report on Internal Control 126 Board of Directors and Committees 22 Global Transformation over Financial Reporting 128 Senior Leadership Group 28 Technology Transformation 70 Report of Independent Registered Inside Back Cover 36 People Transformation Public Accounting Firm General Information 42 At a Glance 72 Consolidated Financial Statements Front cover: 2007 Opel Astra TwinTop There’s a major turnaround under way at GM. We made broad and signifi cant progress in 2006. We accomplished more than people expected, and in many cases, we even surpassed our goals, on or ahead of schedule. We’re not fi nished. There’s much more to do. But our growing confi dence and excitement is rooted in the fact that we’re not just fi xing problems. We’re transforming GM for fundamental, sustainable, long-term success. General Motors Corporation 1 A full-scale production clay model of the 2009 Chevrolet Camaro starts to take shape at GM’s Warren, Michigan, Design Center, Rear Wheel Drive Performance Studio. Bob Lutz Rick Wagoner Fritz Henderson Vice Chairman, Chairman and Vice Chairman and Global Product Development Chief Executive Offi cer Chief Financial Offi cer 2 General Motors Corporation Dear Stockholders: Our company is in a crucial period in its nearly 100-year history. goals of steady growth, solid profi tability and positive cash I’m pleased to report that, in 2006, the entire GM team rose up generation. -

Sharon Novak Charles H. Fine Sloan School of Management

FITTING TEAMS TO THE TASK: PRODUCT DEVELOPMENT VS. OPERATIONS IMPROVEMENT AT SATURN AND NUMMI Sharon Novak Charles H. Fine Sloan School of Management Massachusetts Institute of Technology Cambridge, Massachusetts 02139 February, 1996 Abstract In the automotive industry, Saturn and NUMMI are often touted as exemplars of successful implementation of manufacturing employee involvement. Building on data and extended on-site interviews, this paper explores the differences between the approaches taken at each plant and the relationship between worker involvement and plant performance. Based on this comparison, we offer a model to assess the fit between employee involvement activity emphasis (product development vs. operations improvement) and timescale of the involvement process. 1 FITTING TEAMS TO THE TASK: PRODUCT DEVELOPMENT VS. OPERATIONS IMPROVEMENT AT SATURN AND NUMMI1 From the 1970’s to the present, the achievements of Japanese auto makers such as Toyota, as well as the productive success of the Toyota-General Motors joint venture New United Motor Manufacturing Inc. (NUMMI ) has given rise to a great deal of study on the nature of the Japanese competitive advantage. Much of the current management literature has focused on the team-based organization of such firms, arguing that greater involvement of workers in the automotive process has fueled improvements in productivity. 2 This view, that more worker - based responsibility is better for plant productivity, inspired organizational efforts at both Saturn Corporation, a General Motors -

2003 Audit of the Better Business Bureau Auto Line, Including the State of Florida and the State of Ohio

-.. 4' 2003 AUDIT BBB AUTO LINE INCLUDING: THE STATE OF FLORIDA AND THE STATE OF OHIO Prepared by: MORRISON AND COMPANY 1339 Tatum Gulf Road Cloudland, Georgia 30731 Telephone and Fax: 1-706-398-3789 E-mail Address:jimkitty tvn.net " 4' TABLE OF CONTENTS . ...... ...... ...... ...... ......" . ... .'... .. ..... ... ......'...... ,. .... .. ....... .. ........ '". .... ,.. ... .. .. ... ... .... .. TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE INCEPTIVE INFORMATION. Preface , Page 1 SIOCTION 1: INTRODUCTION. Preface , Page 1 SECTION 2 STATUTORY REQUIREMENTS. .. .. Preface , Page 2 SECTION 3: CONDITIONS. Preface , Page 2 SECTION 4: FINDINGS. Preface , Page 4 A. Manufacturer Warranty Materials. Preface , Page 6 B. Office Practices and Procedures. Preface , Page 7 C. Record-Keeping Procedures. Preface , Page 7 D. Comparative Statistical Analysis. Preface , Page 7 SECTION 5: RECOMMENDATIONS AND CONCLUSIONS. Preface , Page 7 CHAPTER 1: MANUFACTURER WARRANTY MATERIALS. .. .. Chapter 1 , Page 1 SECTION 1: INTRODUCTION. Chapter 1 , Page 1 SECTION 2: STATUTORY REQUIREMENTS. Chapter 1 , Page 2 SECTION 3: CONDITIONS. Chapter 1 , Page 3 , Page 6 SECTION 4: FINDINGS. Chapter 1 A. AM General Sales Corporation (Hummer) ..... " Chapter 1 , Page 11 B. American Honda Motor Company. Chapter 1 , Page 12 (Honda and Acura) . ,.... Chapter 1 , Page 12 C. American Isuzu Motors. Chapter 1 , Page 12 D. General Motors (NATIONAL, FLORIDA, and OHIO) . Chapter 1 , Page 13 E. Hyundai Motor America. Chapter 1 , Page 13 F. Kia Motors America. Chapter 1 , Page 14 G. land Rover of North America. .. Chapter 1 , Page 14 H. lexus Division of Toyota Motor Sales , U. A. .... Chapter 1 , Page 15 I. Nissan North America (Infiniti and Nissan)- ... " Chapter 1 , Page 15 J. Porsche Cars North America. Chapter 1 , Page 16 K. Saturn Corporation. -

Monir “Lou” Sobh 2233 Grady Ridge Trail Duluth, GA 30097

Monir “Lou” Sobh 2233 Grady Ridge Trail Duluth, GA 30097 The following is a brief history of the life and experiences of Lou Sobh. I was born in Torreon, Coahulia Mexico in 1944 where I went on to attend grade school and high school. As a result of the poor economy in Mexico, my parents sought a better opportunity for my four brothers and myself by moving to Gary, Indiana in 1960. After we moved to Gary, I faced the challenge of learning the English language and seeking employment. I started working as a janitor in a Shoppers World department store. At the same time, I worked as a busboy in a local restaurant. My family and I (a total of seven people) lived in a two-bedroom apartment in Gary, Indiana. While working as a janitor, I continued to teach myself English. As the result of hard work, self determination and the example set by my father who worked 15 hours a day, 365 days a year in his grocery store, I learned English well enough in six months to be promoted to a department manager at Shoppers World. I continued to work at the department store for two years. However, I was in a town where steel mills provided good-paying jobs. In 1962, I was employed by the Inland Steel Company in East Chicago, Indiana. I worked there for approximately three years as a steel production worker. U.S. Steel Tubeworks gave me an opportunity to move up in the organization as a Foreman Expediter. I worked for U.S. -

Annual Report

2014 Annual Report NATIONAL AUTOMOBILE DEALERS CHARITABLE FOUNDATION Board of Trustees Robert P. Mallon Paul J. Holloway H. E. Derrick, Jr. James B. Appleton Peter E. Blackstock Chairman Vice Chairman Treasurer Secretary Victory Dealership Mallon Investment Co., Dreher-Holloway, Inc. Derrick Enterprises New Jersey Coalition Group LLC Greenland, Lexington, Virginia of Automotive Retailers Seaside, California Tacoma, Washington New Hampshire Trenton, New Jersey The Chairman’s Message If you were charged with the responsibility of transcending space and time to honor someone, how would you accomplish that? There are many ways you could do that but coupling it William Bradshaw Larry T. Brown William R. Chapin Raymond J. Ciccolo Tarik S. Daoud Leonard W. Fichtner with an endeavor to help others is the best way. The National Automobile Dealers Charitable Bradshaw Automotive Ottawa, Illinois Automotive Hall Village Automotive Long Family Auto Fichtner Chevrolet Group, Inc. of Fame Group Warren, Michigan Laurel, Montana Foundation has assisted hundreds of people in need throughout the years. And it was three Greer, South Carolina Dearborn, Michigan Boston, Massachusetts gentlemen who made a significant mark in their spheres of influence in order to do that. In all three cases, these men were outstanding husbands and fathers, and their accomplishments are forever etched in time through their families and charitable contributions. Joseph J. Sanchez was a man of humble origin who faced hardships such as the death of his father and the debilitating effects of polio at a young age. Thanks to his mother’s guidance, Joe found the strength to not just survive, but flourish. He forged an amazing career as a General Motors executive and served for many years as vice president and general manager of the Oldsmobile Division. -

UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT of NEW YORK ------X : in Re : Chapter 11 Case No

UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK ------------------------------------------------------------------x : In re : Chapter 11 Case No. : MOTORS LIQUIDATION COMPANY, et al., : 09-50026 (REG) f/k/a General Motors Corp., et al. : : Debtors. : (Jointly Administered) : ------------------------------------------------------------------x NOTICE OF (I) APPROVAL OF DISCLOSURE STATEMENT; (II) ESTABLISHMENT OF RECORD DATE; (III) HEARING ON CONFIRMATION OF THE PLAN AND PROCEDURES FOR OBJECTING TO CONFIRMATION OF THE PLAN; AND (IV) PROCEDURES AND DEADLINE FOR VOTING ON THE PLAN TO: ALL HOLDERS OF CLAIMS AGAINST AND INTERESTS IN THE DEBTORS SET FORTH BELOW: Case Tax Identification Other Names Used by Debtors Name of Debtor Number Number in the Past 8 Years Motors Liquidation Company 09-50026 38-0572515 General Motors Corporation (f/k/a General Motors GMC Truck Division Corporation) NAO Fleet Operations GM Corporation GM Corporation-GM Auction Department National Car Rental National Car Sales Automotive Market Research MLCS, LLC 09-50027 38-2577506 Saturn, LLC (f/k/a Saturn, LLC) Saturn Corporation Saturn Motor Car Corporation GM Saturn Corporation Saturn Corporation of Delaware MLCS Distribution Corporation 09-50028 38-2755764 Saturn Distribution Corporation (f/k/a Saturn Distribution Corporation) MLC of Harlem, Inc. 09-13558 20-1426707 Chevrolet-Saturn of Harlem, Inc. (f/k/a Chevrolet-Saturn of Harlem, Inc.) Remediation and Liability 09-50029 38-2529430 Uptown Land Development Corporation Management Company, Inc. Environmental -

General Motors Corporation

General Motors Corporation Company Profile Publication Date: 12 Jun 2008 www.datamonitor.com Datamonitor USA Datamonitor Europe Datamonitor Germany Datamonitor Hong Kong 245 5th Avenue Charles House Kastor & Pollux 2802-2803 Admiralty Centre 4th Floor 108-110 Finchley Road Platz der Einheit 1 Tower 1 New York, NY 10016 London NW3 5JJ 60327 Frankfurt 18 Harcourt Road USA United Kingdom Deutschland Hong Kong t:+1 212 686 7400 t:+44 20 7675 7000 t:+49 69 9754 4517 t:+852 2520 1177 f:+1 212 686 2626 f:+44 20 7675 7500 f:+49 69 9754 4900 f:+852 2520 1165 e:[email protected] e:[email protected] e:[email protected] e:[email protected] General Motors Corporation ABOUT DATAMONITOR Datamonitor is a leading business information company specializing in industry analysis. Through its proprietary databases and wealth of expertise, Datamonitor provides clients with unbiased expert analysis and in depth forecasts for six industry sectors: Healthcare, Technology, Automotive, Energy, Consumer Markets, and Financial Services. The company also advises clients on the impact that new technology and eCommerce will have on their businesses. Datamonitor maintains its headquarters in London, and regional offices in New York, Frankfurt, and Hong Kong. The company serves the world's largest 5000 companies. Datamonitor's premium reports are based on primary research with industry panels and consumers. We gather information on market segmentation, market growth and pricing, competitors and products. Our experts then interpret this data to produce detailed forecasts and actionable recommendations, helping you create new business opportunities and ideas. Our series of company, industry and country profiles complements our premium products, providing top-level information on 10,000 companies, 2,500 industries and 50 countries.