Not a Second Time? John Lennon's Aeolian Cadence Reconsidered

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Martin Pfleiderer

Online publications of the Gesellschaft für Popularmusikforschung/ German Society for Popular Music Studies e. V. Ed. by Eva Krisper and Eva Schuck w w w . gf pm- samples.de/Samples17 / pf l e i de r e r . pdf Volume 17 (2019) - Version of 25 July 2019 BEYOND MAJOR AND MINOR? THE TONALITY OF POPULAR MUSIC AFTER 19601 Martin Pfleiderer While the functional harmonic system of major and minor, with its logic of progression based on leading tones and cadences involving the dominant, has largely departed from European art music in the 20th century, popular music continues to uphold a musical idiom oriented towards major-minor tonality and its semantics. Similar to nursery rhymes and children's songs, it seems that in popular songs, a radiant major affirms plain and happy lyrics, while a darker minor key underlines thoughtful, sad, or gloomy moods. This contrast between light and dark becomes particularly tangible when both, i.e. major and minor, appear in one song. For example, in »Tanze Samba mit mir« [»Dance the Samba with Me«], a hit song composed by Franco Bracardi and sung by Tony Holiday in 1977, the verses in F minor announce a dark mood of desire (»Du bist so heiß wie ein Vulkan. Und heut' verbrenn' ich mich daran« [»You are as hot as a volcano and today I'm burning myself on it«]), which transitions into a happy or triumphant F major in the chorus (»Tanze Samba mit mir, Samba Samba die ganze Nacht« [»Dance the samba with me, samba, samba all night long«]). But can this finding also be transferred to other areas of popular music, such as rock and pop songs of American or British prove- nance, which have long been at least as popular in Germany as German pop songs and folk music? In recent decades, a broad and growing body of research on tonality and harmony in popular music has emerged. -

Chapter 26 Scales a La Mode

CHAPTER 26 SCALES A LA MODE Musical innovation is full of danger to the State, for when modes of music change, the laws of the State always change with them. PLATO WHAT IS A MODE? A mode is a type of scale. Modes are used in music like salsa, jazz, country, rock, fusion, speed metal, and more. The reason the Chapter image is of musicians jamming is that modes are important to understanding (and using) jazz theory, and helpful if you’re trying to understand improvisation. Certain modes go with certain chords. For more information about modes and their specific uses in jazz, read James Levine’s excellent book, Jazz Theory. On the Web at http://is.gd/iqufof These are also called “church modes” because they were first used in the Catholic Church back in Medieval times (remember good old Guido d’ Arezzo?). The names of the modes were taken from the Greek modes, but other than the names, they have no relation to the Greek modes. The two modes that have been used the most, and the only two most people know, are now called the Major and natural minor scales. Their original names were the Ionian mode (Major), and the Aeolian mode (natural minor). The other modes are: dorian, phrygian, lydian, mixolydian, and locrian. Modes are easy to understand. We’ll map out each mode’s series of whole and half steps and use the key of C so there aren’t any sharps or flats to bother with. THE MODES IONIAN Ionian is used in nearly all Western music, from Acid Rock to Zydeco. -

Jazz Harmony Iii

MU 3323 JAZZ HARMONY III Chord Scales US Army Element, School of Music NAB Little Creek, Norfolk, VA 23521-5170 13 Credit Hours Edition Code 8 Edition Date: March 1988 SUBCOURSE INTRODUCTION This subcourse will enable you to identify and construct chord scales. This subcourse will also enable you to apply chord scales that correspond to given chord symbols in harmonic progressions. Unless otherwise stated, the masculine gender of singular is used to refer to both men and women. Prerequisites for this course include: Chapter 2, TC 12-41, Basic Music (Fundamental Notation). A knowledge of key signatures. A knowledge of intervals. A knowledge of chord symbols. A knowledge of chord progressions. NOTE: You can take subcourses MU 1300, Scales and Key Signatures; MU 1305, Intervals and Triads; MU 3320, Jazz Harmony I (Chord Symbols/Extensions); and MU 3322, Jazz Harmony II (Chord Progression) to obtain the prerequisite knowledge to complete this subcourse. You can also read TC 12-42, Harmony to obtain knowledge about traditional chord progression. TERMINAL LEARNING OBJECTIVES MU 3323 1 ACTION: You will identify and write scales and modes, identify and write chord scales that correspond to given chord symbols in a harmonic progression, and identify and write chord scales that correspond to triads, extended chords and altered chords. CONDITION: Given the information in this subcourse, STANDARD: To demonstrate competency of this task, you must achieve a minimum of 70% on the subcourse examination. MU 3323 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Section Subcourse Introduction Administrative Instructions Grading and Certification Instructions L esson 1: Sc ales and Modes P art A O verview P art B M ajor and Minor Scales P art C M odal Scales P art D O ther Scales Practical Exercise Answer Key and Feedback L esson 2: R elating Chord Scales to Basic Four Note Chords Practical Exercise Answer Key and Feedback L esson 3: R elating Chord Scales to Triads, Extended Chords, and Altered Chords Practical Exercise Answer Key and Feedback Examination MU 3323 3 ADMINISTRATIVE INSTRUCTIONS 1. -

I. the Term Стр. 1 Из 93 Mode 01.10.2013 Mk:@Msitstore:D

Mode Стр. 1 из 93 Mode (from Lat. modus: ‘measure’, ‘standard’; ‘manner’, ‘way’). A term in Western music theory with three main applications, all connected with the above meanings of modus: the relationship between the note values longa and brevis in late medieval notation; interval, in early medieval theory; and, most significantly, a concept involving scale type and melody type. The term ‘mode’ has always been used to designate classes of melodies, and since the 20th century to designate certain kinds of norm or model for composition or improvisation as well. Certain phenomena in folksong and in non-Western music are related to this last meaning, and are discussed below in §§IV and V. The word is also used in acoustical parlance to denote a particular pattern of vibrations in which a system can oscillate in a stable way; see Sound, §5(ii). For a discussion of mode in relation to ancient Greek theory see Greece, §I, 6 I. The term II. Medieval modal theory III. Modal theories and polyphonic music IV. Modal scales and traditional music V. Middle East and Asia HAROLD S. POWERS/FRANS WIERING (I–III), JAMES PORTER (IV, 1), HAROLD S. POWERS/JAMES COWDERY (IV, 2), HAROLD S. POWERS/RICHARD WIDDESS (V, 1), RUTH DAVIS (V, 2), HAROLD S. POWERS/RICHARD WIDDESS (V, 3), HAROLD S. POWERS/MARC PERLMAN (V, 4(i)), HAROLD S. POWERS/MARC PERLMAN (V, 4(ii) (a)–(d)), MARC PERLMAN (V, 4(ii) (e)–(i)), ALLAN MARETT, STEPHEN JONES (V, 5(i)), ALLEN MARETT (V, 5(ii), (iii)), HAROLD S. POWERS/ALLAN MARETT (V, 5(iv)) Mode I. -

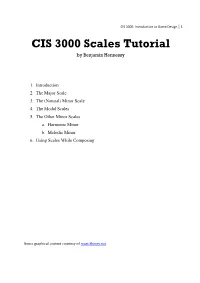

CIS 3000 Scales Tutorial

CIS 3000: Introduction to Game Design 1 CIS 3000 Scales Tutorial by Benjamin Hennessy 1. Introduction 2. The Major Scale 3. The (Natural) Minor Scale 4. The Modal Scales 5. The Other Minor Scales a. Harmonic Minor b. Melodic Minor 6. Using Scales While Composing Some graphical content courtesy of musictheory.net . CIS 3000: Introduction to Game Design 2 Introduction A scale is an ordered sequence of notes. Typical ly, a scale spans one octave (twelve half steps on the piano roll, ie from C to C) and contains seven note s (eight if we count the repeated note at the octave). Which seven notes we select out of the possible twelve in a one octave range determines what kind of scale we have. Note: there are scales which have more or less than seven notes, but we will only be focusing on those with se ven, or the heptatonic scales. The Major Scale First we’ll discuss the major scale . A major scale is made up of this sequence of whole steps (W) and half steps ( h): W W h W W W h Knowing this sequence is useful because you can create scales regardless of the starting note. Here is an example of a major scale starting on C in both traditional staff notation and Reason’s piano roll notation: You might notice how the re are no sharps or flats in the C scale, or that all of the notes correspond to the wh ite keys on the piano roll. Here’s what the major scale looks like when we start on the D instead: Notice how there a re now two sharps in the scale, corresponding to the two black keys on the piano roll. -

A-Beginner-Guide-To-Modes.Pdf

A BEGINNER GUIDE TO MODES Here are a few charts to help break down modes, including scale patterns, chord patterns, and the characteristic “colour note / chord” within each scale. Just like with the idea of parallel major and minor scales, you can choose to write solely within one scale (say, D dorian), OR you can borrow a chord from a parallel mode while still using chords from your original scale (i.e., writing in F minor [aeolian] and using a Db major chord, but also using a Bb major chord, borrowed from Dorian mode). The Modes by Numeric Pattern (Rose boxes indicate the scale’s ‘colour note’ or what gives it its character; blue boxes show a potential secondary colour note.) MODE 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 IONIAN 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 DORIAN 1 2 b3 4 5 6 b7 PHRYGIAN 1 b2 b3 4 5 b6 b7 LYDIAN 1 2 3 #4 5 6 7 MIXOLYDIAN 1 2 3 4 5 6 b7 AEOLIAN 1 2 b3 4 5 b6 b7 LOCRIAN 1 b2 b3 4 b5 b6 b7 IONIAN mode is the major scale, so this mode begins on the 1st degree of the major scale. DORIAN mode begins on the 2nd scale degree of the relative ionian mode (major scale) PHRYGIAN mode begins on the 3rd scale degree of the relative ionian mode (major scale) LYDIAN mode begins on the 4th scale degree of the relative ionian mode (major scale) MIXOLYDIAN mode begins on the 5th scale degree of the relative ionian mode (major scale) AEOLIAN mode (minor scale) begins on the 6th degree of the relative ionian mode (major scale). -

Improvisation Aeolian Mode

Improvisation: From Minor Pentatonic Scale to Aeolian Mode In this lesson students will explore their musical creativity through improvisation by developing ideas for melodic lines using the Aeolian mode. Students will gain an aural and theoretical understanding of the Aeolian mode through improvisation and analysis of a minor key Reggae groove in our Notation Mixer. The clip below features Berklee College of Music students as they talk about what improvisation means to them. For additional resources on improvisation, check out our Improvisation Unit in our PULSE Study Room. Access free resources to enhance this lesson by joining Berklee PULSE. Outcomes: • Students will gain an aural and theoretical understanding of the Aeolian mode through improvisation and analysis. Materials: • PULSE improvisation video • PULSE minor pentatonic and Aeolian scale material • Preferred instrument INSTRUCTIONAL ACTIVITY IDEAS Exposition of Material 1. Review Lesson 1 After watching the improvisation video above students will: o Reflect upon their composition process in Lesson 1 and discuss how their perception of improvisation and musical expression has progressed. o Review the minor pentatonic scale. 2. Review Mode What is a mode? o Modes have seven notes, and are built using a pattern of half steps and whole steps, just like the major and minor scales. Each mode has a “characteristic note,” a note that sets it apart from the other modes. Musicians often use the major scale as the starting point when talking about a mode, because each mode starts on one of the scale degrees of the major scale. We will use the C major scale (key of C) as the starting point for each mode, but you can build modes in any major scale. -

THE MODES of the MAJOR SCALE -Written by David Taub

THE MODES OF THE MAJOR SCALE -written by David Taub Now that you had a basic modal overview in the previous written lesson we can discuss each mode in detail and how to go about utilizing them. In order to thoroughly understand the modes we will need to look at the interval structure that defines each mode and then match them with corresponding chords and progressions where they can be applied. Remember that the modes are all just variations of the major scale and you will be playing the modes by shifting emphasis to a different note in the parent or mother major scale. Once you know all six major scale patterns up and down the neck you know all the modes of the major scale. You wont have to learn another six shapes or scale patterns for each mode – you can get to all the modes through the major scales. Refer to the past lessons and learn all six major scales and scale links up and down the neck and practice in all keys. The illustration below shows each mode in order and its interval structure. Many of the modes are very similar, some just one interval difference. For example the only difference between Aeolian and Dorian is the Aeolian mode has a b6 while the Dorian mode has a major 6th. Mixolydian is just like the Ionian mode or major scale but with a b7 and Lydian is also like the Ionian mode but with a #4. Phrygian is just like Aeolian except it has a b2. So many of the modes are very similar but these slight differences will give you a totally different mood and totally different sounds – it’s absolutely amazing! Keep in mind that each mode has its own specific sound, texture, and mood. -

The Perfect Mode Pitches C to Eb Or D to F Natural

6 The Harp Therapy Journal --summer201~1 consisting of three semitones from the The perfect mode pitches C to Eb or D to F natural. This interval occurs other places within the byJulieAnn Smith BM, MA, IRTF, VAHTP modes and scales by the way but it is the occurrence of this interval between Do and Mi of any mode that is the How often do you start a therapeutic music session and ask yourself, "What do I deciding sound between the major and play?" This is a serious question. When thinking about musical modes I have often minor mode groups. wondered about one being superior. In considering music for therapeutic settings I Throughout time there has been also have wondered what mode might be an all-encompassing mode. Is there a mode a lot of emphasis placed on how we that could effectively work in any therapeutic situation; at least as a starting point? view the third note of any mode and its Therapeutic musicians are so often presented with the dilemma of what to play first, role in music with regards to our mood what key to play in or what mode would work, among other factors. So in considering and how the music affects us. There is which mode would be most important, there are several factors to consider. a different opinion about what affect, 1. Matching and meeting the patient's needs. Is she in pain? Is he sad, anxious, with- effect or emotion music should evoke. drawn, or depressed? Does she need relief from pain or anxiety? Does he just want Socrates and others prescribed that to feel better? Obviously our goal as therapeutic musicians is to address the patient's music should be played that was the needs. -

Rock Harmony Reconsidered: Tonal, Modal and Contrapuntal Voice&

DOI: 10.1111/musa.12085 BRAD OSBORN ROCK HARMONY RECONSIDERED:TONAL,MODAL AND CONTRAPUNTAL VOICE-LEADING SYSTEMS IN RADIOHEAD A great deal of the harmony and voice leading in the British rock group Radiohead’s recorded output between 1997 and 2011 can be heard as elaborating either traditional tonal structures or establishing pitch centricity through purely contrapuntal means.1 A theory that highlights these tonal and contrapuntal elements departs from a number of developed approaches in rock scholarship: first, theories that focus on fretboard-ergonomic melodic gestures such as axe- fall and box patterns;2 second, a proclivity towards analysing chord roots rather than melody and voice leading;3 and third, a methodology that at least tacitly conflates the ideas of hypermetric emphasis and pitch centre. Despite being initially yoked to the musical conventions of punk and grunge (and their attendant guitar-centric compositional practice), Radiohead’s 1997– 2011 corpus features few of the characteristic fretboard gestures associated with rock harmony (partly because so much of this music is composed at the keyboard) and thus demands reconsideration on its own terms. This mature period represents the fullest expression of Radiohead’s unique harmonic, formal, timbral and rhythmic idiolect,4 as well as its evolved instrumentation, centring on keyboard and electronics. The point here is not to isolate Radiohead’s harmonic practice as something fundamentally different from all rock which came before it. Rather, by depending less on rock-paradigmatic gestures such as pentatonic box patterns on the fretboard, their music invites us to consider how such practices align with existing theories of rock harmony while diverging from others. -

KEY Natural Minor (Aeolian Mode)

CHORDS IN EACH KEY -written by David Taub There are three different types of minor scales – Natural Minor or Aeolian mode, Melodic Minor, and Harmonic Minor. These scales sound different from major scales because they are based on a different pattern of intervals. To create a minor scale from harmonizing the natural minor scale start on the root note and go up the scale using the pattern: whole step, half step, whole step, whole step, half step, whole step, whole step. The first chord will always be minor, the second chord will always be diminished, the third chord will always be major, the fourth chord will always be minor, the fifth chord will always be minor, the sixth chord will always be major, and the seventh chord will always be major. Due to the three different minor scales there are more choices of chords when writing music in minor key as compared to major key. For discussional purposes and to keep things relatively simple the chart below illustrates the minor key chordal options when we compile the Natural Minor scale, (in black), with the ascending version of the Melodic Minor scale, (in red). As illustrated you have many different chordal options when writing in minor key so experiment and let you ear guide you to the best sounding chords like you like the best and that fit the music you are creating. Remember that the chart below is just a guide and that any chord can appear in any key, the chords below are just much more likely to appear in each given key as they are made from combinations of notes in the given scale. -

Modal Scales

Modal Scales Commonly used in jazz harmony, the modal scales are a series of seven different scales each with their own pattern of whole and half steps. To make them easier to understand we can relate these patterns to the white notes of the piano and the C major scale. When you play all the white notes on a piano, starting on C and ending on C you have a C major scale. This pattern of whole and half steps is also called the Ionian mode. W W H W W W H When you play all the white notes on a piano, this time starting on D and ending on D, you have a different order of whole and half steps. Therefore we have a different scale. This is called the Dorian mode. W H W W W H W There is a different modal scale starting on each of the seven differently named white notes of the piano, each with a distinctive sound. Over the next few pages we will explore the different modes. All the white notes starting on E is the Phrygian mode H W W W H W W And all the white notes starting on F is the Lydian mode W W W H W W H Starting on G is the Mixolydian mode W W H W W H W Printable Music Theory Books - Level Four Page 7 © 2011 The Fun Music Company Pty Ltd Starting on A is the Aeolian mode, which is the same as the natural minor scale. The final mode starting on B is the Locrian mode.