Chapter 26 Scales a La Mode

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

4. Non-Heptatonic Modes

Tagg: Everyday Tonality II — 4. Non‐heptatonic modes 151 4. Non‐heptatonic modes If modes containing seven different scale degrees are heptatonic, eight‐note modes are octatonic, six‐note modes hexatonic, those with five pentatonic, while four‐ and three‐note modes are tetratonic and tritonic. Now, even though the most popular pentatonic modes are sometimes called ‘gapped’ because they contain two scale steps larger than those of the ‘church’ modes of Chapter 3 —doh ré mi sol la and la doh ré mi sol, for example— they are no more incomplete FFBk04Modes2.fm. 2014-09-14,13:57 or empty than the octatonic start to example 70 can be considered cluttered or crowded.1 Ex. 70. Vigneault/Rochon (1973): Je chante pour (octatonic opening phrase) The point is that the most widespread convention for numbering scale degrees (in Europe, the Arab world, India, Java, China, etc.) is, as we’ve seen, heptatonic. So, when expressions like ‘thirdless hexatonic’ occur in this chapter it does not imply that the mode is in any sense deficient: it’s just a matter of using a quasi‐global con‐ vention to designate a particular trait of the mode. Tritonic and tetratonic Tritonic and tetratonic tunes are common in many parts of the world, not least in traditional music from Micronesia and Poly‐ nesia, as well as among the Māori, the Inuit, the Saami and Native Americans of the great plains.2 Tetratonic modes are also found in Christian psalm and response chanting (ex. 71), while the sound of children chanting tritonic taunts can still be heard in playgrounds in many parts of the world (ex. -

Martin Pfleiderer

Online publications of the Gesellschaft für Popularmusikforschung/ German Society for Popular Music Studies e. V. Ed. by Eva Krisper and Eva Schuck w w w . gf pm- samples.de/Samples17 / pf l e i de r e r . pdf Volume 17 (2019) - Version of 25 July 2019 BEYOND MAJOR AND MINOR? THE TONALITY OF POPULAR MUSIC AFTER 19601 Martin Pfleiderer While the functional harmonic system of major and minor, with its logic of progression based on leading tones and cadences involving the dominant, has largely departed from European art music in the 20th century, popular music continues to uphold a musical idiom oriented towards major-minor tonality and its semantics. Similar to nursery rhymes and children's songs, it seems that in popular songs, a radiant major affirms plain and happy lyrics, while a darker minor key underlines thoughtful, sad, or gloomy moods. This contrast between light and dark becomes particularly tangible when both, i.e. major and minor, appear in one song. For example, in »Tanze Samba mit mir« [»Dance the Samba with Me«], a hit song composed by Franco Bracardi and sung by Tony Holiday in 1977, the verses in F minor announce a dark mood of desire (»Du bist so heiß wie ein Vulkan. Und heut' verbrenn' ich mich daran« [»You are as hot as a volcano and today I'm burning myself on it«]), which transitions into a happy or triumphant F major in the chorus (»Tanze Samba mit mir, Samba Samba die ganze Nacht« [»Dance the samba with me, samba, samba all night long«]). But can this finding also be transferred to other areas of popular music, such as rock and pop songs of American or British prove- nance, which have long been at least as popular in Germany as German pop songs and folk music? In recent decades, a broad and growing body of research on tonality and harmony in popular music has emerged. -

How to Construct Modes

How to Construct Modes Modes can be derived from a major scale. The true application of a mode is one in which the notes and harmony are derived primarily from a mode. Modal scales are used, however, over the chord of the moment in a non-modal tune, although it would not be a modal melody in the strictest definition. There are seven basic modes and you may derive them utilizing a major scale as reference. The names of the 7 modes are: Ionian, Dorian, Phrygian, Lydian, Mixolydian, Aeolian, and Locrian Each scale or mode has distinctive note relationships which give it its unique sound. The simplest way to construct modes is to construct a seven note scale starting from each successive note in a major scale. By referencing the diatonic notes in the original major scale (ionian mode), all seven modes can be created from each of the major scale notes. • Ionian is scale degree l to l (one octave higher or lower) • Dorian is 2 to 2 • Phrygian is 3 to 3 • Lydian is 4 to 4 • Mixolydian is 5 to 5 • Aeolian is 6 to 6 • Locrian is 7 to 7 However, there is a better way to construct any mode: To construct any mode, think of the scale degree it is associated with. For example, dorian can be associated with the second degree of a major scale. As we have seen, modes may be constructed by building a diatonic 7 note scale beginning on each successive major scale degree. But you need to be able to construct on any note any of the seven modes without first building a major scale. -

The 17-Tone Puzzle — and the Neo-Medieval Key That Unlocks It

The 17-tone Puzzle — And the Neo-medieval Key That Unlocks It by George Secor A Grave Misunderstanding The 17 division of the octave has to be one of the most misunderstood alternative tuning systems available to the microtonal experimenter. In comparison with divisions such as 19, 22, and 31, it has two major advantages: not only are its fifths better in tune, but it is also more manageable, considering its very reasonable number of tones per octave. A third advantage becomes apparent immediately upon hearing diatonic melodies played in it, one note at a time: 17 is wonderful for melody, outshining both the twelve-tone equal temperament (12-ET) and the Pythagorean tuning in this respect. The most serious problem becomes apparent when we discover that diatonic harmony in this system sounds highly dissonant, considerably more so than is the case with either 12-ET or the Pythagorean tuning, on which we were hoping to improve. Without any further thought, most experimenters thus consign the 17-tone system to the discard pile, confident in the knowledge that there are, after all, much better alternatives available. My own thinking about 17 started in exactly this way. In 1976, having been a microtonal experimenter for thirteen years, I went on record, dismissing 17-ET in only a couple of sentences: The 17-tone equal temperament is of questionable harmonic utility. If you try it, I doubt you’ll stay with it for long.1 Since that time I have become aware of some things which have caused me to change my opinion completely. -

The New Dictionary of Music and Musicians

The New GROVE Dictionary of Music and Musicians EDITED BY Stanley Sadie 12 Meares - M utis London, 1980 376 Moda Harold Powers Mode (from Lat. modus: 'measure', 'standard'; 'manner', 'way'). A term in Western music theory with three main applications, all connected with the above meanings of modus: the relationship between the note values longa and brevis in late medieval notation; interval, in early medieval theory; most significantly, a concept involving scale type and melody type. The term 'mode' has always been used to designate classes of melodies, and in this century to designate certain kinds of norm or model for composition or improvisation as well. Certain pheno mena in folksong and in non-Western music are related to this last meaning, and are discussed below in §§IV and V. The word is also used in acoustical parlance to denote a particular pattern of vibrations in which a system can oscillate in a stable way; see SOUND, §5. I. The term. II. Medieval modal theory. III. Modal theo ries and polyphonic music. IV. Modal scales and folk song melodies. V. Mode as a musicological concept. I. The term I. Mensural notation. 2. Interval. 3. Scale or melody type. I. MENSURAL NOTATION. In this context the term 'mode' has two applications. First, it refers in general to the proportional durational relationship between brevis and /onga: the modus is perfectus (sometimes major) when the relationship is 3: l, imperfectus (sometimes minor) when it is 2 : I. (The attributives major and minor are more properly used with modus to distinguish the rela tion of /onga to maxima from the relation of brevis to longa, respectively.) In the earliest stages of mensural notation, the so called Franconian notation, 'modus' designated one of five to seven fixed arrangements of longs and breves in particular rhythms, called by scholars rhythmic modes. -

THE MODES of ANCIENT GREECE by Elsie Hamilton

THE MODES OF ANCIENT GREECE by Elsie Hamilton * * * * P R E F A C E Owing to requests from various people I have consented with humility to write a simple booklet on the Modes of Ancient Greece. The reason for this is largely because the monumental work “The Greek Aulos” by Kathleen Schlesinger, Fellow of the Institute of Archaeology at the University of Liverpool, is now unfortunately out of print. Let me at once say that all the theoretical knowledge I possess has been imparted to me by her through our long and happy friendship over many years. All I can claim as my own contribution is the use I have made of these Modes as a basis for modern composition, of which details have been given in Appendix 3 of “The Greek Aulos”. Demonstrations of Chamber Music in the Modes were given in Steinway Hall in 1917 with the assistance of some of the Queen’s Hall players, also 3 performances in the Etlinger Hall of the musical drama “Sensa”, by Mabel Collins, in 1919. A mime “Agave” was performed in the studio of Madame Matton-Painpare in 1924, and another mime “The Scorpions of Ysit”, at the Court Theatre in 1929. In 1935 this new language of Music was introduced at Stuttgart, Germany, where a small Chamber Orchestra was trained to play in the Greek Modes. Singers have also found little difficulty in singing these intervals which are not those of our modern well-tempered system, of which fuller details will be given later on in this booklet. -

Jazz Harmony Iii

MU 3323 JAZZ HARMONY III Chord Scales US Army Element, School of Music NAB Little Creek, Norfolk, VA 23521-5170 13 Credit Hours Edition Code 8 Edition Date: March 1988 SUBCOURSE INTRODUCTION This subcourse will enable you to identify and construct chord scales. This subcourse will also enable you to apply chord scales that correspond to given chord symbols in harmonic progressions. Unless otherwise stated, the masculine gender of singular is used to refer to both men and women. Prerequisites for this course include: Chapter 2, TC 12-41, Basic Music (Fundamental Notation). A knowledge of key signatures. A knowledge of intervals. A knowledge of chord symbols. A knowledge of chord progressions. NOTE: You can take subcourses MU 1300, Scales and Key Signatures; MU 1305, Intervals and Triads; MU 3320, Jazz Harmony I (Chord Symbols/Extensions); and MU 3322, Jazz Harmony II (Chord Progression) to obtain the prerequisite knowledge to complete this subcourse. You can also read TC 12-42, Harmony to obtain knowledge about traditional chord progression. TERMINAL LEARNING OBJECTIVES MU 3323 1 ACTION: You will identify and write scales and modes, identify and write chord scales that correspond to given chord symbols in a harmonic progression, and identify and write chord scales that correspond to triads, extended chords and altered chords. CONDITION: Given the information in this subcourse, STANDARD: To demonstrate competency of this task, you must achieve a minimum of 70% on the subcourse examination. MU 3323 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Section Subcourse Introduction Administrative Instructions Grading and Certification Instructions L esson 1: Sc ales and Modes P art A O verview P art B M ajor and Minor Scales P art C M odal Scales P art D O ther Scales Practical Exercise Answer Key and Feedback L esson 2: R elating Chord Scales to Basic Four Note Chords Practical Exercise Answer Key and Feedback L esson 3: R elating Chord Scales to Triads, Extended Chords, and Altered Chords Practical Exercise Answer Key and Feedback Examination MU 3323 3 ADMINISTRATIVE INSTRUCTIONS 1. -

I. the Term Стр. 1 Из 93 Mode 01.10.2013 Mk:@Msitstore:D

Mode Стр. 1 из 93 Mode (from Lat. modus: ‘measure’, ‘standard’; ‘manner’, ‘way’). A term in Western music theory with three main applications, all connected with the above meanings of modus: the relationship between the note values longa and brevis in late medieval notation; interval, in early medieval theory; and, most significantly, a concept involving scale type and melody type. The term ‘mode’ has always been used to designate classes of melodies, and since the 20th century to designate certain kinds of norm or model for composition or improvisation as well. Certain phenomena in folksong and in non-Western music are related to this last meaning, and are discussed below in §§IV and V. The word is also used in acoustical parlance to denote a particular pattern of vibrations in which a system can oscillate in a stable way; see Sound, §5(ii). For a discussion of mode in relation to ancient Greek theory see Greece, §I, 6 I. The term II. Medieval modal theory III. Modal theories and polyphonic music IV. Modal scales and traditional music V. Middle East and Asia HAROLD S. POWERS/FRANS WIERING (I–III), JAMES PORTER (IV, 1), HAROLD S. POWERS/JAMES COWDERY (IV, 2), HAROLD S. POWERS/RICHARD WIDDESS (V, 1), RUTH DAVIS (V, 2), HAROLD S. POWERS/RICHARD WIDDESS (V, 3), HAROLD S. POWERS/MARC PERLMAN (V, 4(i)), HAROLD S. POWERS/MARC PERLMAN (V, 4(ii) (a)–(d)), MARC PERLMAN (V, 4(ii) (e)–(i)), ALLAN MARETT, STEPHEN JONES (V, 5(i)), ALLEN MARETT (V, 5(ii), (iii)), HAROLD S. POWERS/ALLAN MARETT (V, 5(iv)) Mode I. -

Convergent Evolution in a Large Cross-Cultural Database of Musical Scales

Convergent evolution in a large cross-cultural database of musical scales John M. McBride1,* and Tsvi Tlusty1,2,* 1Center for Soft and Living Matter, Institute for Basic Science, Ulsan 44919, South Korea 2Departments of Physics and Chemistry, Ulsan National Institute of Science and Technology, Ulsan 44919, South Korea *[email protected], [email protected] August 3, 2021 Abstract We begin by clarifying some key terms and ideas. We first define a scale as a sequence of notes (Figure 1A). Scales, sets of discrete pitches used to generate Notes are pitch categories described by a single pitch, melodies, are thought to be one of the most uni- although in practice pitch is variable so a better descrip- versal features of music. Despite this, we know tion is that notes are regions of semi-stable pitch centered relatively little about how cross-cultural diversity, around a representative (e.g., mean, meadian) frequency or how scales have evolved. We remedy this, in [10]. Thus, a scale can also be thought of as a sequence of part, we assemble a cross-cultural database of em- mean frequencies of pitch categories. However, humans pirical scale data, collected over the past century process relative frequency much better than absolute fre- by various ethnomusicologists. We provide sta- quency, such that a scale is better described by the fre- tistical analyses to highlight that certain intervals quency of notes relative to some standard; this is typically (e.g., the octave) are used frequently across cul- taken to be the first note of the scale, which is called the tures. -

Scales, Modes, Intervals and the Circle of Fifths

Scales, Modes, Intervals and the Circle of Fifths The word scale comes from the Latin word meaning ladder. So you can think of a scale climbing the rungs of the ladder which is represented by the stave. The degrees of a scale You have to have a note on every single line or space. Each degree of the scale has a special name: • 1st degree: the tonic • 2nd degree: the supertonic • 3rd degree: the mediant • 4th degree: the subdominant • 5th degree: the dominant • 6th degree: the submediant • 7th degree: the leading note (or leading tone) The 8th degree of the scale is actually the tonic but an octave higher. For that reason when naming the degrees of the scale you should always call it the 1st degree. MAJOR SCALES One of the more common types of scale is the major scale. Major scales are defined by their combination of semitones and tones (whole steps and half steps): Tone – Tone – Semitone – Tone – Tone – Tone – Semitone Or in whole steps and half steps it would be: Whole – Whole – Half – Whole – Whole – Whole – Half Major scale formula MINOR SCALES The second type of scale that we’re going to look at is the minor scale. Minor scales also have seven notes like the major scale but they’re defined by having a flattened third. This means that the third note of the scale is three semitones above the first note, unlike major scales where the third note of the scale is four semitones above. A MELODIC MINOR SCALE There are three different types of minor scale: • the NATURAL minor • the HARMONIC minor • the MELODIC minor Each type of minor scale uses a slightly different formula of semitones and tones but they all have that minor third. -

Jazz Improvisation for the B-Flat Soprano Trumpet: an Introductory Text for Teaching Basic Theoretical and Performance Principles

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1973 Jazz Improvisation for the B-Flat Soprano Trumpet: an Introductory Text for Teaching Basic Theoretical and Performance Principles. John Willys Mccauley Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Mccauley, John Willys, "Jazz Improvisation for the B-Flat Soprano Trumpet: an Introductory Text for Teaching Basic Theoretical and Performance Principles." (1973). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 2554. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/2554 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1.T he sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page{s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. -

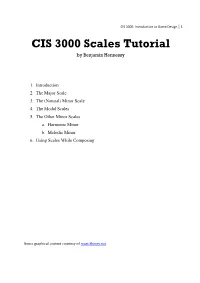

CIS 3000 Scales Tutorial

CIS 3000: Introduction to Game Design 1 CIS 3000 Scales Tutorial by Benjamin Hennessy 1. Introduction 2. The Major Scale 3. The (Natural) Minor Scale 4. The Modal Scales 5. The Other Minor Scales a. Harmonic Minor b. Melodic Minor 6. Using Scales While Composing Some graphical content courtesy of musictheory.net . CIS 3000: Introduction to Game Design 2 Introduction A scale is an ordered sequence of notes. Typical ly, a scale spans one octave (twelve half steps on the piano roll, ie from C to C) and contains seven note s (eight if we count the repeated note at the octave). Which seven notes we select out of the possible twelve in a one octave range determines what kind of scale we have. Note: there are scales which have more or less than seven notes, but we will only be focusing on those with se ven, or the heptatonic scales. The Major Scale First we’ll discuss the major scale . A major scale is made up of this sequence of whole steps (W) and half steps ( h): W W h W W W h Knowing this sequence is useful because you can create scales regardless of the starting note. Here is an example of a major scale starting on C in both traditional staff notation and Reason’s piano roll notation: You might notice how the re are no sharps or flats in the C scale, or that all of the notes correspond to the wh ite keys on the piano roll. Here’s what the major scale looks like when we start on the D instead: Notice how there a re now two sharps in the scale, corresponding to the two black keys on the piano roll.