A Biological Rationale for Musical Scales

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

4. Non-Heptatonic Modes

Tagg: Everyday Tonality II — 4. Non‐heptatonic modes 151 4. Non‐heptatonic modes If modes containing seven different scale degrees are heptatonic, eight‐note modes are octatonic, six‐note modes hexatonic, those with five pentatonic, while four‐ and three‐note modes are tetratonic and tritonic. Now, even though the most popular pentatonic modes are sometimes called ‘gapped’ because they contain two scale steps larger than those of the ‘church’ modes of Chapter 3 —doh ré mi sol la and la doh ré mi sol, for example— they are no more incomplete FFBk04Modes2.fm. 2014-09-14,13:57 or empty than the octatonic start to example 70 can be considered cluttered or crowded.1 Ex. 70. Vigneault/Rochon (1973): Je chante pour (octatonic opening phrase) The point is that the most widespread convention for numbering scale degrees (in Europe, the Arab world, India, Java, China, etc.) is, as we’ve seen, heptatonic. So, when expressions like ‘thirdless hexatonic’ occur in this chapter it does not imply that the mode is in any sense deficient: it’s just a matter of using a quasi‐global con‐ vention to designate a particular trait of the mode. Tritonic and tetratonic Tritonic and tetratonic tunes are common in many parts of the world, not least in traditional music from Micronesia and Poly‐ nesia, as well as among the Māori, the Inuit, the Saami and Native Americans of the great plains.2 Tetratonic modes are also found in Christian psalm and response chanting (ex. 71), while the sound of children chanting tritonic taunts can still be heard in playgrounds in many parts of the world (ex. -

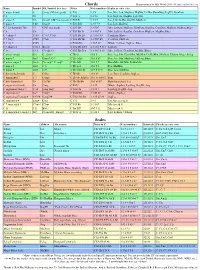

Chords and Scales 30/09/18 3:21 PM

Chords and Scales 30/09/18 3:21 PM Chords Charts written by Mal Webb 2014-18 http://malwebb.com Name Symbol Alt. Symbol (best first) Notes Note numbers Scales (in order of fit). C major (triad) C Cmaj, CM (not good) C E G 1 3 5 Ion, Mix, Lyd, MajPent, MajBlu, DoHar, HarmMaj, RagPD, DomPent C 6 C6 C E G A 1 3 5 6 Ion, MajPent, MajBlu, Lyd, Mix C major 7 C∆ Cmaj7, CM7 (not good) C E G B 1 3 5 7 Ion, Lyd, DoHar, RagPD, MajPent C major 9 C∆9 Cmaj9 C E G B D 1 3 5 7 9 Ion, Lyd, MajPent C 7 (or dominant 7th) C7 CM7 (not good) C E G Bb 1 3 5 b7 Mix, LyDom, PhrDom, DomPent, RagCha, ComDim, MajPent, MajBlu, Blues C 9 C9 C E G Bb D 1 3 5 b7 9 Mix, LyDom, RagCha, DomPent, MajPent, MajBlu, Blues C 7 sharp 9 C7#9 C7+9, C7alt. C E G Bb D# 1 3 5 b7 #9 ComDim, Blues C 7 flat 9 C7b9 C7alt. C E G Bb Db 1 3 5 b7 b9 ComDim, PhrDom C 7 flat 5 C7b5 C E Gb Bb 1 3 b5 b7 Whole, LyDom, SupLoc, Blues C 7 sharp 11 C7#11 Bb+/C C E G Bb D F# 1 3 5 b7 9 #11 LyDom C 13 C 13 C9 add 13 C E G Bb D A 1 3 5 b7 9 13 Mix, LyDom, DomPent, MajBlu, Blues C minor (triad) Cm C-, Cmin C Eb G 1 b3 5 Dor, Aeo, Phr, HarmMin, MelMin, DoHarMin, MinPent, Ukdom, Blues, Pelog C minor 7 Cm7 Cmin7, C-7 C Eb G Bb 1 b3 5 b7 Dor, Aeo, Phr, MinPent, UkDom, Blues C minor major 7 Cm∆ Cm maj7, C- maj7 C Eb G B 1 b3 5 7 HarmMin, MelMin, DoHarMin C minor 6 Cm6 C-6 C Eb G A 1 b3 5 6 Dor, MelMin C minor 9 Cm9 C-9 C Eb G Bb D 1 b3 5 b7 9 Dor, Aeo, MinPent C diminished (triad) Cº Cdim C Eb Gb 1 b3 b5 Loc, Dim, ComDim, SupLoc C diminished 7 Cº7 Cdim7 C Eb Gb A(Bbb) 1 b3 b5 6(bb7) Dim C half diminished Cø -

Year 9 Blues & Improvisation Duration 13-14 Weeks

Topic: Year 9 Blues & Improvisation Duration 13-14 Weeks Key vocabulary: Core knowledge questions Powerful knowledge crucial to commit to long term Links to previous and future topics memory 12-Bar Blues, Blues 45. What are the key features of blues music? • Learn about the history, origins and Links to chromatic Notes from year 8. Chord Sequence, 46. What are the main chords used in the 12-bar blues sequence? development of the Blues and its characteristic Links to Celtic Music from year 8 due to Improvisation 47. What other styles of music led to the development of blues 12-bar Blues structure exploring how a walking using improvisation. Links to form & Syncopation Blues music? bass line is developed from a chord structure from year 9 and Hooks & Riffs Scale Riffs 48. Can you explain the term improvisation and what does it mean progression. in year 9. Fills in blues music? • Explore the effect of adding a melodic Solos 49. Can you identify where the chords change in a 12-bar blues improvisation using the Blues scale and the Make links to music from other cultures Chords I, IV, V, sequence? effect which “swung”rhythms have as used in and traditions that use riff and ostinato- Blues Song Lyrics 50. Can you explain what is meant by ‘Singin the Blues’? jazz and blues music. based structures, such as African Blues Songs 51. Why did music play an important part in the lives of the African • Explore Ragtime Music as a type of jazz style spirituals and other styles of Jazz. -

Martin Pfleiderer

Online publications of the Gesellschaft für Popularmusikforschung/ German Society for Popular Music Studies e. V. Ed. by Eva Krisper and Eva Schuck w w w . gf pm- samples.de/Samples17 / pf l e i de r e r . pdf Volume 17 (2019) - Version of 25 July 2019 BEYOND MAJOR AND MINOR? THE TONALITY OF POPULAR MUSIC AFTER 19601 Martin Pfleiderer While the functional harmonic system of major and minor, with its logic of progression based on leading tones and cadences involving the dominant, has largely departed from European art music in the 20th century, popular music continues to uphold a musical idiom oriented towards major-minor tonality and its semantics. Similar to nursery rhymes and children's songs, it seems that in popular songs, a radiant major affirms plain and happy lyrics, while a darker minor key underlines thoughtful, sad, or gloomy moods. This contrast between light and dark becomes particularly tangible when both, i.e. major and minor, appear in one song. For example, in »Tanze Samba mit mir« [»Dance the Samba with Me«], a hit song composed by Franco Bracardi and sung by Tony Holiday in 1977, the verses in F minor announce a dark mood of desire (»Du bist so heiß wie ein Vulkan. Und heut' verbrenn' ich mich daran« [»You are as hot as a volcano and today I'm burning myself on it«]), which transitions into a happy or triumphant F major in the chorus (»Tanze Samba mit mir, Samba Samba die ganze Nacht« [»Dance the samba with me, samba, samba all night long«]). But can this finding also be transferred to other areas of popular music, such as rock and pop songs of American or British prove- nance, which have long been at least as popular in Germany as German pop songs and folk music? In recent decades, a broad and growing body of research on tonality and harmony in popular music has emerged. -

How to Construct Modes

How to Construct Modes Modes can be derived from a major scale. The true application of a mode is one in which the notes and harmony are derived primarily from a mode. Modal scales are used, however, over the chord of the moment in a non-modal tune, although it would not be a modal melody in the strictest definition. There are seven basic modes and you may derive them utilizing a major scale as reference. The names of the 7 modes are: Ionian, Dorian, Phrygian, Lydian, Mixolydian, Aeolian, and Locrian Each scale or mode has distinctive note relationships which give it its unique sound. The simplest way to construct modes is to construct a seven note scale starting from each successive note in a major scale. By referencing the diatonic notes in the original major scale (ionian mode), all seven modes can be created from each of the major scale notes. • Ionian is scale degree l to l (one octave higher or lower) • Dorian is 2 to 2 • Phrygian is 3 to 3 • Lydian is 4 to 4 • Mixolydian is 5 to 5 • Aeolian is 6 to 6 • Locrian is 7 to 7 However, there is a better way to construct any mode: To construct any mode, think of the scale degree it is associated with. For example, dorian can be associated with the second degree of a major scale. As we have seen, modes may be constructed by building a diatonic 7 note scale beginning on each successive major scale degree. But you need to be able to construct on any note any of the seven modes without first building a major scale. -

The 17-Tone Puzzle — and the Neo-Medieval Key That Unlocks It

The 17-tone Puzzle — And the Neo-medieval Key That Unlocks It by George Secor A Grave Misunderstanding The 17 division of the octave has to be one of the most misunderstood alternative tuning systems available to the microtonal experimenter. In comparison with divisions such as 19, 22, and 31, it has two major advantages: not only are its fifths better in tune, but it is also more manageable, considering its very reasonable number of tones per octave. A third advantage becomes apparent immediately upon hearing diatonic melodies played in it, one note at a time: 17 is wonderful for melody, outshining both the twelve-tone equal temperament (12-ET) and the Pythagorean tuning in this respect. The most serious problem becomes apparent when we discover that diatonic harmony in this system sounds highly dissonant, considerably more so than is the case with either 12-ET or the Pythagorean tuning, on which we were hoping to improve. Without any further thought, most experimenters thus consign the 17-tone system to the discard pile, confident in the knowledge that there are, after all, much better alternatives available. My own thinking about 17 started in exactly this way. In 1976, having been a microtonal experimenter for thirteen years, I went on record, dismissing 17-ET in only a couple of sentences: The 17-tone equal temperament is of questionable harmonic utility. If you try it, I doubt you’ll stay with it for long.1 Since that time I have become aware of some things which have caused me to change my opinion completely. -

Kūnqǔ in Practice: a Case Study

KŪNQǓ IN PRACTICE: A CASE STUDY A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN THEATRE OCTOBER 2019 By Ju-Hua Wei Dissertation Committee: Elizabeth A. Wichmann-Walczak, Chairperson Lurana Donnels O’Malley Kirstin A. Pauka Cathryn H. Clayton Shana J. Brown Keywords: kunqu, kunju, opera, performance, text, music, creation, practice, Wei Liangfu © 2019, Ju-Hua Wei ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to express my gratitude to the individuals who helped me in completion of my dissertation and on my journey of exploring the world of theatre and music: Shén Fúqìng 沈福庆 (1933-2013), for being a thoughtful teacher and a father figure. He taught me the spirit of jīngjù and demonstrated the ultimate fine art of jīngjù music and singing. He was an inspiration to all of us who learned from him. And to his spouse, Zhāng Qìnglán 张庆兰, for her motherly love during my jīngjù research in Nánjīng 南京. Sūn Jiàn’ān 孙建安, for being a great mentor to me, bringing me along on all occasions, introducing me to the production team which initiated the project for my dissertation, attending the kūnqǔ performances in which he was involved, meeting his kūnqǔ expert friends, listening to his music lessons, and more; anything which he thought might benefit my understanding of all aspects of kūnqǔ. I am grateful for all his support and his profound knowledge of kūnqǔ music composition. Wichmann-Walczak, Elizabeth, for her years of endeavor producing jīngjù productions in the US. -

Development of Musical Scales in Europe

RABINDRA BHARATI UNIVERSITY VOCAL MUSIC DEPARTMENT COURSE - B.A. ( Compulsory Course ) (CBCS) 2020 Semester - II , Paper - I Teacher - Sri Partha Pratim Bhowmik History of Western Music Development of musical scales in Europe In the 8th century B.C., The musical atmosphere of ancient Greece introduced its development by the influence of then popular aristocratic music. That music was melody- based and the root of that music was rural folk-songs. In each and every country, the development of music was rooted in the folk-songs. The European Aristocratic Music of the Christian Era had been inspired by the developed Greek music. In the 5th century B.C. the renowned Greek Mathematician Pythagoras had first established a relation between science and music. Before him, the scale of Greek music was pentatonic. Pythagoras changed the scale into hexatonic pattern and later into heptatonic pattern. Greek musicians applied the alphabets to indicate the notes of their music. For the natural notes they used the alphabets in normal position and for the deformed notes, the alphabets turned upside down [deformed notes= Vikrita svaras]. The musical instruments, they had invented are – Aulos, Salpinx, pan-pipes, harp, lyre, syrinx etc. In the western music, the term ‘scale’ is derived from Latin word ‘scala’, ie, the ladder; scale means an ascent or descent formation of the musical notes. Each and every scale has a starting note, called ‘tonic note’ [‘tone - tonic’ not the Health-Tonic]. In the Ancient Greece, the musical scale had been formed with the help of lyre , a string instrument, having normally 5 or 6 or 7 strings. -

Minor Pentatonic & Blues- the Five Box Shapes

Minor Pentatonic & Blues- The Five Box Shapes Now we will add one note to the minor pentatonic scale and turn it into the six-note blues scale. Pentatonic & Blues scales are the most commonly used scales in most genres of music. We can add the flat 5, (b5), or blue note to the pentatonic scale, making it a six-note scale called the Blues Scale. That b5, or blue note, adds a lot of tension and color to the scale. These are “must-know” scales especially for blues and rock so be sure to memorize them and add them to your soloing repertoire. Most of the time when soloing with minor pentatonic scales you can also use the blues scale. To be safe, at first, use the blue note more in passing for color, don’t hang on it too long. Hanging on that flat five too long can sound a bit dissonant. It’s a great note though, so experiment with it and let your ear guide you. The five box shapes illustrated below cover the entire neck. These five positions are the architecture to build licks and runs as well as to connect into longer expanded scales. To work freely across the entire neck you will want to memorize all five positions as well as the two expanded scales illustrated on the next page. These scale shapes are moveable. The key is determined by the root notes illustrated in black. If you want to solo in G minor pentatonic play box #1 using your first finger starting at the 3rd fret on the low E-string and play the shape from there. -

The New Dictionary of Music and Musicians

The New GROVE Dictionary of Music and Musicians EDITED BY Stanley Sadie 12 Meares - M utis London, 1980 376 Moda Harold Powers Mode (from Lat. modus: 'measure', 'standard'; 'manner', 'way'). A term in Western music theory with three main applications, all connected with the above meanings of modus: the relationship between the note values longa and brevis in late medieval notation; interval, in early medieval theory; most significantly, a concept involving scale type and melody type. The term 'mode' has always been used to designate classes of melodies, and in this century to designate certain kinds of norm or model for composition or improvisation as well. Certain pheno mena in folksong and in non-Western music are related to this last meaning, and are discussed below in §§IV and V. The word is also used in acoustical parlance to denote a particular pattern of vibrations in which a system can oscillate in a stable way; see SOUND, §5. I. The term. II. Medieval modal theory. III. Modal theo ries and polyphonic music. IV. Modal scales and folk song melodies. V. Mode as a musicological concept. I. The term I. Mensural notation. 2. Interval. 3. Scale or melody type. I. MENSURAL NOTATION. In this context the term 'mode' has two applications. First, it refers in general to the proportional durational relationship between brevis and /onga: the modus is perfectus (sometimes major) when the relationship is 3: l, imperfectus (sometimes minor) when it is 2 : I. (The attributives major and minor are more properly used with modus to distinguish the rela tion of /onga to maxima from the relation of brevis to longa, respectively.) In the earliest stages of mensural notation, the so called Franconian notation, 'modus' designated one of five to seven fixed arrangements of longs and breves in particular rhythms, called by scholars rhythmic modes. -

THE MODES of ANCIENT GREECE by Elsie Hamilton

THE MODES OF ANCIENT GREECE by Elsie Hamilton * * * * P R E F A C E Owing to requests from various people I have consented with humility to write a simple booklet on the Modes of Ancient Greece. The reason for this is largely because the monumental work “The Greek Aulos” by Kathleen Schlesinger, Fellow of the Institute of Archaeology at the University of Liverpool, is now unfortunately out of print. Let me at once say that all the theoretical knowledge I possess has been imparted to me by her through our long and happy friendship over many years. All I can claim as my own contribution is the use I have made of these Modes as a basis for modern composition, of which details have been given in Appendix 3 of “The Greek Aulos”. Demonstrations of Chamber Music in the Modes were given in Steinway Hall in 1917 with the assistance of some of the Queen’s Hall players, also 3 performances in the Etlinger Hall of the musical drama “Sensa”, by Mabel Collins, in 1919. A mime “Agave” was performed in the studio of Madame Matton-Painpare in 1924, and another mime “The Scorpions of Ysit”, at the Court Theatre in 1929. In 1935 this new language of Music was introduced at Stuttgart, Germany, where a small Chamber Orchestra was trained to play in the Greek Modes. Singers have also found little difficulty in singing these intervals which are not those of our modern well-tempered system, of which fuller details will be given later on in this booklet. -

Nora-Louise Müller the Bohlen-Pierce Clarinet An

Nora-Louise Müller The Bohlen-Pierce Clarinet An Introduction to Acoustics and Playing Technique The Bohlen-Pierce scale was discovered in the 1970s and 1980s by Heinz Bohlen and John R. Pierce respectively. Due to a lack of instruments which were able to play the scale, hardly any compositions in Bohlen-Pierce could be found in the past. Just a few composers who work in electronic music used the scale – until the Canadian woodwind maker Stephen Fox created a Bohlen-Pierce clarinet, instigated by Georg Hajdu, professor of multimedia composition at Hochschule für Musik und Theater Hamburg. Hence the number of Bohlen- Pierce compositions using the new instrument is increasing constantly. This article gives a short introduction to the characteristics of the Bohlen-Pierce scale and an overview about Bohlen-Pierce clarinets and their playing technique. The Bohlen-Pierce scale Unlike the scales of most tone systems, it is not the octave that forms the repeating frame of the Bohlen-Pierce scale, but the perfect twelfth (octave plus fifth), dividing it into 13 steps, according to various mathematical considerations. The result is an alternative harmonic system that opens new possibilities to contemporary and future music. Acoustically speaking, the octave's frequency ratio 1:2 is replaced by the ratio 1:3 in the Bohlen-Pierce scale, making the perfect twelfth an analogy to the octave. This interval is defined as the point of reference to which the scale aligns. The perfect twelfth, or as Pierce named it, the tritave (due to the 1:3 ratio) is achieved with 13 tone steps.