Green Belts: a Greener Future

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Draft Topic Paper 5: Natural Environment/Biodiversity

Wiltshire Local Development Framework Working towards a Core Strategy for Wiltshire Draft topic paper 5: Natural environment/biodiversity Wiltshire Core Strategy Consultation June 2011 Wiltshire Council Information about Wiltshire Council services can be made available on request in other languages including BSL and formats such as large print and audio. Please contact the council on 0300 456 0100, by textphone on 01225 712500 or by email on [email protected]. Wiltshire Core Strategy Natural Environment Topic Paper 1 This paper is one of 18 topic papers, listed below, which form part of the evidence base in support of the emerging Wiltshire Core Strategy. These topic papers have been produced in order to present a coordinated view of some of the main evidence that has been considered in drafting the emerging Core Strategy. It is hoped that this will make it easier to understand how we had reached our conclusions. The papers are all available from the council website: Topic Paper TP1: Climate Change TP2: Housing TP3: Settlement Strategy TP4: Rural Issues (signposting paper) TP5: Natural Environment/Biodiversity TP6: Water Management/Flooding TP7: Retail TP8: Economy TP9: Planning Obligations TP10: Built and Historic Environment TP11:Transport TP12: Infrastructure TP13: Green Infrastructure TP14:Site Selection Process TP15:Military Issues TP16:Building Resilient Communities TP17: Housing Requirement Technical Paper TP18: Gypsy and Travellers 2 Table of Contents Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................5 -

Wangari Maathai

WANGARI MAATHAI Throughout Africa (as in much of the world) women hold primary responsibility for tilling the fields, deciding what to plant, nurturing the crops, and harvesting the food. They are the first to become aware of environmental damage that harms agricultural production: If the well goes dry, they are the ones concerned about finding new sources of water and who must walk long distances to fetch it. As mothers, they notice when the food they feed their family is tainted with pollutants or impurities: they can see it in the tears of their children and hear it in their babies’ cries. Wangari Maathai, Kenya’s foremost environmentalist and women’s rights advocate, founded the Green Belt Movement on Earth Day 1977, encouraging farmers (70 percent of whom are women) to plant “greenbelts” to stop soil erosion, provide shade, and create a source of lumber and firewood. She distributed seedlings to rural women and set up an incentive system for each seedling that survived. To date, the movement has planted more than fifteen million trees, produced income for eighty thousand people in Kenya alone, and has expanded its efforts to more than thirty African countries, the United States, and Haiti. Maathai won the Africa Prize for her work in preventing hunger, and was heralded by the Kenyan government—controlled press as an exemplary citizen. A few years later, when Maathai denounced President Daniel Toroitich arap Moi’s proposal to erect a sixty-two-story skyscraper in the middle of Nairobi’s largest park (graced by a four-story statue of Moi himself), officials warned her to curtail her criticism. -

Area Plan Proposal for London Has Been Developed and in This Booklet You Will Find Information on the Changes Proposed for London

Post Office Ltd Network Change Programme Area Plan Proposal London 2 Contents 1. Introduction 2. Proposed Local Area Plan 3. The Role of Postwatch 4. List of Post Office® branches proposed for closure 5. List of Post Office® branches proposed to remain in the Network • Frequently Asked Questions Leaflet • Map of the Local Area Plan • Branch Access Reports - information on proposed closing branches and details of alternative branches in the Area 3 4 1. Introduction The Government has recognised that fewer people are using Post Office® branches, partly because traditional services, including benefit payments and other services are now available in other ways, such as online or directly through banks. It has concluded that the overall size and shape of the network of Post Office® branches (“the Network”) needs to change. In May 2007, following a national public consultation, the Government announced a range of proposed measures to modernise and reshape the Network and put it on a more stable footing for the future. A copy of the Government’s response to the national public consultation (“the Response Document”) can be obtained at www.dti.gov.uk/consultations/page36024.html. Post Office Ltd has now put in place a Network Change Programme (“the Programme”) to implement the measures proposed by the Government. The Programme will involve the compulsory compensated closure of up to 2,500 Post Office® branches (out of a current Network of 14,300 branches), with the introduction of about 500 service points known as “Outreaches” to mitigate the impact of the proposed closures. Compensation will be paid to those subpostmasters whose branches are compulsorily closed under the Programme. -

Bristol Food Networking

BRISTOL FOOD NETWORK Bristol’s local food update2012 community project news · courses · publications · events march–april Spring is nearly springing. The wild garlic is poking through, the Alexanders are growing vigorously, and it’s feeling very tempting to start sowing things in the veg bed. Across the city, new growing projects are sprouting forth, too. In this issue we hear from Avon Wildlife Trust about ‘Feed Bristol’; the Severn Project who have expanded into Whitchurch; and the Horfield accessible allotment and edible forest, who have their grand opening in April. Please email any suggestions for content of the May–June newsletter to [email protected] by 9 April. Events, courses listings and appeals can now be updated at any time on our website www.bristolfoodnetwork.org Bristol food networking The recent Green Capital ‘Future City We will need volunteers to help: Bristol Independents Day Conversations’ have shown how much n publicise the event 4 July 2012 interest there is in Bristol in food issues n photograph open gardens The Bristol Independents campaign – and how much is going on. There are n assist groups hosting openings, etc is gearing-up to celebrate ‘Bristol some great opportunites coming up this Independents Day’ on 4 July. Volunteers Bristol local food networking sessions year to help Bristol’s food projects and are needed to help: businesses flourish: Volunteers are sought to host monthly n Spread the word meet ups for anyone involved in the Bristol n Talk to traders Get Growing Garden Trail food sector who is working towards a n Get community groups involved, etc 9–10 June 2012 better food system for Bristol. -

North Hertfordshire Green Belt Review

99 North Hertfordshire Green Belt Review July 2016 North Hertfordshire Local Plan 2011 - 2031 Evidence Base Report North Hertfordshire Green Belt Review July 2016 2 North Hertfordshire Green Belt Review July 2016 Contents 1. Background and Approach to the Review…………………………………. 5 PART ONE: ASSESSMENT OF THE CURRENT GREEN BELT, VILLAGES IN THE GREEN BELT AND POTENTIAL DEVELOPMENT SITES IN THE GREEN BELT 2. Strategic Review of the Green Belt…………………………………...………….. 9 2.1 Background to Review 2.2 Role and purpose of Green Belt 2.3 The National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF) 2.4 Methodology 2.5 Assessment - existing Green Belt 2.6 Checking the unrestricted sprawl of large built-up areas 2.7 Preventing neighbouring towns merging into one another 2.8 Safeguarding the countryside from encroachment 2.9 Preserving the setting and special character of Historic Towns 2.10 Overall contribution to Green Belt purposes 3. Refined Review of the Green Belt……………………………………………..…. 33 4. Analysis of Villages in the Green Belt…………………………………………... 67 4.1 Purpose and Method of Appraisal 4.2 NHDC Proposed Policy Context 4.3 Analysis of Contribution to the Green Belt 5. Analysis of Potential Development Sites in the Green Belt…………………. 99 5.1 Introduction 5.2 Methodology - potential development sites 5.3 Assessment of Potential Development Sites PART TWO: ASSESSMENT OF POTENTIAL ADDITIONS TO THE GREEN BELT 6. Assessment of Countryside beyond the Green Belt………………………….. 135 6.1 Introduction 6.2 Role and purpose of Green Belt 6.3 Methodology – potential Green Belt areas -

Green Belt Movement of Kenya : a Gender Analysis

Lakehead University Knowledge Commons,http://knowledgecommons.lakeheadu.ca Electronic Theses and Dissertations Retrospective theses 2000 Green Belt Movement of Kenya : a gender analysis Wakesho, Catherine http://knowledgecommons.lakeheadu.ca/handle/2453/1672 Downloaded from Lakehead University, KnowledgeCommons The Green Belt Movement of Kenya: A Gender Analysis BY CATHERINE WAKESHO DEPARTMENT OF SOCIOLOGY LAKEHEAD UNVERSITY THUNDER BAY, ONTARIO A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in Partial Fulfillment of the requirements For the Degree of Masters of Arts ® Catherine Wakesho, 2000 ProQuest Number: 10611456 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Pro ProQuest 10611456 Published by ProQuest LLC (2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106 - 1346 ABSTRACT The Green Belt Movement of Kenya is an environmental conservation movement that began in 1977 as a project of women planting trees. It has since grown into a popular movement in Kenya expanding its goals of environmental rehabilitation to include broader socio-political issues in the Kenyan context. To date the GBM has been the subject of studies, which have analysed various phases of its development. -

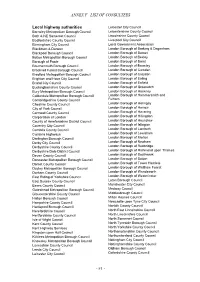

Annex F –List of Consultees

ANNEX F –LIST OF CONSULTEES Local highway authorities Leicester City Council Barnsley Metropolitan Borough Council Leicestershire County Council Bath & NE Somerset Council Lincolnshire County Council Bedfordshire County Council Liverpool City Council Birmingham City Council Local Government Association Blackburn & Darwen London Borough of Barking & Dagenham Blackpool Borough Council London Borough of Barnet Bolton Metropolitan Borough Council London Borough of Bexley Borough of Poole London Borough of Brent Bournemouth Borough Council London Borough of Bromley Bracknell Forest Borough Council London Borough of Camden Bradford Metropolitan Borough Council London Borough of Croydon Brighton and Hove City Council London Borough of Ealing Bristol City Council London Borough of Enfield Buckinghamshire County Council London Borough of Greenwich Bury Metropolitan Borough Council London Borough of Hackney Calderdale Metropolitan Borough Council London Borough of Hammersmith and Cambridgeshire County Council Fulham Cheshire County Council London Borough of Haringey City of York Council London Borough of Harrow Cornwall County Council London Borough of Havering Corporation of London London Borough of Hillingdon County of Herefordshire District Council London Borough of Hounslow Coventry City Council London Borough of Islington Cumbria County Council London Borough of Lambeth Cumbria Highways London Borough of Lewisham Darlington Borough Council London Borough of Merton Derby City Council London Borough of Newham Derbyshire County Council London -

Coventry and Warwickshire Joint Green Belt Study: Stage 2 Final

Coventry & Warwickshire Joint Green Belt Study Coventry City Council, North Warwickshire Borough Council, Nuneaton and Bedworth Borough Council, Rugby Borough Council, Stratford-on-Avon District Council and Warwick District Council Stage 2 Final Report for North Warwickshire Borough Council and Stratford-on-Avon District Council Prepared by LUC April 2016 Project Title: Joint Green Belt Study Client: Coventry City Council, North Warwickshire Borough Council, Nuneaton and Bedworth Borough Council, Rugby Borough Council, Stratford-on-Avon District Council and Warwick District Council Version Date Version Details Prepared by Checked by Approved by 1.0 23rd March Draft Josh Allen Philip Smith Philip Smith 2016 2.0 13th April Final Draft Report Josh Allen Philip Smith Philip Smith 2016 3.0 18th April Final Report Josh Allen Philip Smith Philip Smith 2016 Last saved: 18/04/2016 16:46 Coventry & Warwickshire Joint Green Belt Study Coventry City Council, North Warwickshire Borough Council, Nuneaton and Bedworth Borough Council, Rugby Borough Council, Stratford-on- Avon District Council and Warwick District Council Stage 2 Final Report for North Warwickshire Borough Council and Stratford-on-Avon District Council Prepared by LUC April 2016 Planning & EIA LUC LONDON Offices also in: Land Use Consultants Ltd Registered in England Design 43 Chalton Street Bristol Registered number: 2549296 Landscape Planning London Glasgow Registered Office: Landscape Management NW1 1JD Edinburgh 43 Chalton Street Ecology T +44 (0)20 7383 5784 London NW1 1JD Mapping -

Overcrowding Data 2009-10 - Quarter 4 & Baseline Return

London Assembly Planning and Housing Committee Combined Evidence Received:.pdf version Investigation: Overcrowding in London’s Social Rented Housing Contents Organisation Evidence Reference Page Number Number London Borough of Bromley OSRH001 2 Family Mosaic OSRH002 44 East Thames Group OSRH003 46 Affinity Sutton OSRH004 50 Homes and Communities Agency (London) OSRH005 54 South-East London Region OSRH006 60 Hexagon Housing Association OSRH007 62 London Borough of Redbridge OSRH008 66 Kier Partnership Homes OSRH009 87 Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) OSRH010 95 London Borough of Richmond upon Thames OSRH011 99 Citizens Advice OSRH012 103 Notting Hill Housing OSRH013 107 National Housing Federation OSRH014 110 London Borough of Waltham Forest OSRH015 114 Peabody Trust OSRH016 147 London Borough of Croydon OSRH017 153 London Borough of Camden OSRH018 156 G15 Group OSRH019 165 North London Sub Regional Partnership OSRH020 167 City of London OSRH021 172 Genesis Group OSRH022 174 London Borough of Barking and Dagenham OSRH023 179 St George Regeneration OSRH024 188 The Hyde Group OSRH025 190 London Borough of Hounslow OSRH026 194 London Borough of Harrow OSRH027 201 East London Sub Regional Partnership OSRH028 208 London School of Economics (LSE) OSRH029 215 Developers Group OSRH030 218 Amicus Horizon OSRH031 222 CIH (Chartered Institute of Housing) London OSRH032 225 London Borough of Southwark OSRH033 232 West London Region OSRH034 283 London Councils OSRH035 286 London Borough of Merton OSRH036 291 London Borough of Brent OSRH037 -

APPENDIX B the North West London Joint Health Overview & Scrutiny

APPENDIX B The North West London Joint Health Overview & Scrutiny Committee Terms of Reference 1. Membership Membership of the Joint Health Overview and Scrutiny Committee (JHOSC) is one nominated voting member from each participating council, plus one other nominated member to whom the vote can be transferred (on the basis of that member being an elected member of the council they are representing). Alternatively, a Borough can nominate one voting member only. A substitute member can be nominated by the Borough. The vote can also be transferred to the substitute member where he or she is an elected member of the council and the voting member is unavailable. The JHOSC consists of the following authorities: London Borough of Brent London Borough of Ealing London Borough of Hammersmith & Fulham London Borough of Harrow London Borough of Hounslow Royal Borough of Kensington & Chelsea London Borough of Richmond City of Westminster 2. Quorum The committee will require at least six members in attendance to be quorate. 3. Chair and Vice Chair The JHOSC will elect its own chair and vice chair. Elections will take place on an annual basis each May, or as soon as practical thereafter, such as to allow for any annual changes to the committee’s membership. The Chair and Vice Chair shall not be members of the same authority or the same political party. 4. Duration It is important the JHOSC operates on the basis of being able to contribute to the effective scrutiny of cross-borough health issues. The JHOSC should provide a forum for cross borough engagement and consultation between its member local authorities, and health service commissioners and providers. -

Six Sigma Certification

ABOUT INTERPRO Interdisciplinary and Professional Programs SIX SIGMA (InterPro) develops and delivers programs and services that enable engineers, managers, and CERTIFICATION technical professionals to be more effective, productive, and competitive. InterPro extends Learn to Use Six Sigma to Improve and enhances the programs, capabilities, and Effi ciency, Customer Satisfaction, relationships of the faculty and affi liates of the and Your Bottom Line College of Engineering by offering graduate degree programs, distance learning, non-credit public short courses, professional certifi cation programs, and conferences. Professional development short courses Graduate degree programs currently and certifi cation programs include: offered include: Toyota Kata Automotive Engineering online Lean-Six Sigma Certifi cation Design Science Lean Manufacturing Certifi cation Energy Systems Engineering online Lean Product Development Certifi cation Engineering Sustainable Systems Lean Offi ce Certifi cation Entrepreneurship Lean Healthcare Certifi cation Financial Engineering UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING Lean Supply Chain for Healthcare Global Automotive and Manufacturing Certifi cation Engineering online Lean Supply Chain & Warehouse Integrated Microsystems Management Certifi cation Manufacturing Engineering online Lean Pharmaceutical Certifi cation Pharmaceutical Engineering SIX SIGMA FROM THE CHOOSE FROM ONLINE OR Michigan Human Factors Engineering Robotics and Autonomous Vehicles Short Course LEADERS AND BEST CLASSROOM OPTIONS online Indicates programs with an online delivery option. Emerging Automotive Technologies At the University of Michigan, you’re taught by Transactional Service/Operations Hybrid and Electric Vehicles Graduate Certifi cates of Advanced Studies Green Belt and Black Belt Online internationally respected industrial engineering Financial Management for Engineers in Engineering (CASE) are also available in Manufacturing Green Belt and Dynamics of Heavy Duty Trucks some of the programs. -

Local Plan Was Adopted on December 16Th 1997

B RISTOL L OCAL P LAN The city council wishes to thank all the people of Bristol who were involved in planning the future of our city by making comments on the formulation of this Plan. After five years of debate involving consultation, a public local inquiry and modifications, the Bristol Local Plan was adopted on December 16th 1997. The Plan consists of this written statement and a separate Proposals Map. For further information, please contact Strategic and Citywide Policy Team Directorate of Planning, Transport and Development Services Brunel House St George’s Road Bristol BS1 5UY Telephone: 903 6723 / 903 6724 / 903 6725 / 903 6727 Produced by: Planning content The Directorate of Planning, Transport and Development Services Technical Production Technical Services and Word Processing Bureau of the Planning Directorate Graphic & 3-D Design Unit of the Policy Co-ordinator and Chief Executive’s Office Printed by Bristol City Council Contract Services – Printing and Stationery Department, Willway Street, Bedminster GRA1865 20452 P&S Printed on recycled paper ADOPTED BRISTOL LOCAL PLAN DECEMBER 1997 P REFACE The Bristol Local Plan was formally adopted in December 1997 after a long and lively debate involving many thousands of local people and numerous organisations with a stake in the city’s future. Bristol now has up to date statutory planning policies covering the whole city. This Plan will guide development up to 2001 and form the basis for a review taking Bristol into the 21st Century. The Plan sets out to protect open space, industrial land, housing, shopping and local services and to promote the quality of life for all the citizens of Bristol.