Colombia Baseline Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

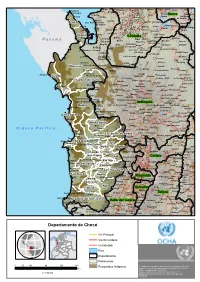

Departamento De Chocó

! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! !! ! !! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! !!! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! !!! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! !Neiva ! !Belen ! Zapata El Limo!n! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! !!! ! ! ! ! La!guneta ! Po! paya! n ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! !Cuiva !Piza ! ! ! ! ! ! Sapzurro ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !Mulatos ! !! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! !!! ! ! ! ! ! ! !El Ye! so ! ! !! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! Capurgana ! ! !! ! !! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! El Pital Zapata ! !! ! ! ! ! ! A! chi ! !! ! !! ! !! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! Neiva Sucre El Mellito! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! !! !! !! ! ! ! !Cuenca San R!oque !Acandi ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !Caribia ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! La Sierpita ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! Sehebe ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! !! !! ! ! ! ! Boyaca ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! !! !! ! ! ! ! !Necocli ! ! ! ! ! !! ! !! ! ! La U! nión ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Cecilia ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! G!uamal ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !Providencia Acandí El Bobal !! ! ! ! ! ! ! Casa Blanca ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! !Gavalda ! ! ! ! ! ! -

Resolución No. 5024 Chocó

cNs Comalia riSCIOrtal Electoral COLOMBIA RESOLUCIÓN No. 5024 DE 2019 (18 de septiembre) Por medio del cual se adoptan decisiones en relación con la inscripción irregular de cédulas de ciudadanía, en los Municipios de Alto Baudo, Atrato, Bagado, Bojaya, El Cantón de San Pablo, Carmen del Darién, Certeguí, Condoto, El Carmen de Atrato, El Litoral del San Juan, lstmina, Juradó, Lloró, Medio Baudó, Medio San Juan, Nóvita, Nuqui, Río !ro, Río Quito, Riosucio, Sipl, Tadó y Unión Panamericana, Departamento del Chocó, para las elecciones de autoridades locales de 27 de octubre del año 2019. EL CONSEJO NACIONAL ELECTORAL En ejercicio de sus atribuciones Constitucionales y legales, en especial las conferidas en los artículos 265 numeral 6° y 316 de la Constitución Política, 4° de la ley 163 de 1994, la Resolución No. 2857 de 2018 del Consejo Nacional Electoral y con fundamento en los siguientes: 1. HECHOS Y ACTUACIONES ADMINISTRATIVAS 1.1. El 27 de octubre de 2019 se realizarán en todo el país las elecciones para elegir Autoridades Locales (Gobernadores, Alcaldes, Diputados, Concejales y Miembros de Juntas Administradoras Locales). 1.2. En reparto especial del 14 de noviembre de 2018, correspondió al Despacho del Magistrado Jorge Enrique Rozo Rodríguez, conocer de las investigaciones, por presuntas irregularidades en la inscripción de cédulas de ciudadanía, en los municipios del Departamento de Chocó. 1.3. Mediante los siguientes Autos el Consejo Nacional Electoral, a través del Magistrado Jorge Enrique Rozo Rodriguez, asumió el conocimiento y ordenó iniciar el procedimiento administrativo para determinar la posible inscripción irregular de algunas cédulas de ciudadania en los Municipios de Alto Baudo, Atrato, Bagadó, Bojaya, El Cantón del San Pablo, Carmen del Darién, Cértegui, Condoto, El Carmen de Atrato, El Litoral del San Juan, Istmina, Juradó, Lloró, Medio Baudó, Medio San Juan, Nóvita, Nuquí, Río Iro, Río Quito, Riosucio, Sipí, Tadó y Unión Panamericana, Departamento del Chocó. -

Plan Operativo Anual (POA)

PLAN DE INVERSIONES “TODOS POR EL PACÍFICO - CHOCÓ” PLAN OPERATIVO ANUAL POA 2015 Empresa de Acueducto y Alcantarillado de Pereira S.A. E.S.P Pereira, 28 de agosto de 2015 “TODOS POR EL PACÍFICO -CHOCÓ” PLAN OPERATIVO ANUAL POA 2015 CONTRATO INTERADMINISTRATIVO No. 186 de 2010 Pereira, 28 de agosto de 2015 Tabla de contenido 1 BREVE DIAGNÓSTICO DEL ACCESO A AGUA Y SANEAMIENTO: .................................................. 6 2 JUSTIFICACION DE LAS VARIACIONES DEL POA 4 RESPECTO AL POG APROBADO. .................. 58 3 COORDINACION DE OBRAS DEL PROGRAMA CON LAS OBRAS DE RECURSOS EXTERNOS. ..... 58 4 ESTRATEGIA PARA EL SISTEMA DE SEGUIMIENTO DE LA CALIDAD DE AGUA........................... 58 5 ACTIVIDADES QUE FINALIZAN POSTERIOR AL CONTRATO 186 DE 2010 .................................. 59 6 EXPLICACION DE ALGUNOS DE LOS PRODUCTOS MENCIONADOS EN EL POA. ........................ 61 7 COORDINACION INTERINSTITUCIONAL SEDE QUIBDO ............................................................. 61 8 MATRIZ DE RESULTADOS........................................................................................................... 61 9 PLAN DE ADQUISICIONES .......................................................................................................... 61 10 CRONOGRAMA ...................................................................................................................... 61 11 ESTADO DE LOS PRODUCTOS A DICIEMBRE 31 DE 2014 ...................................................... 62 12 LIMITANTES DE LA EJECUCIÓN DEL POA 2015 -

Diapositiva 1

Communitarian State: Development for All, and its Application to the Pacific National Planning Department June 3rd, 2007 Index 1.1. WWhhaatt isis mmeaeanntt byby ththee PPaacciifificc RRegegiioon?n? 2.2. WWhhyy hhaaveve aa ppoolilicycy foforr ththee PPaciacifificc?? 3.3. HHowow iiss ththee ppoolilicycy fforor ththee PPaacifcificic ddeeveveloloppeed?d? 4.4. WWhhaatt dodoeess ththee ssttrraateteggyy conconsisistst oof?f? • AA vivisisioonn comcombibinedned wiwithth stratstrategiegicc oobjbjectiectivveses • AA rolrolee forfor thethe PaciPacifificc wiwithithinn thethe NNatiationonalal DeDevelvelopopmentment PPllanan − DemocDemocratiraticc popolliicycy wwithith ssociociaallllyy iintegntegratedrated assassiistastancence − PovPovertyerty rereductductiionon aandnd propromotingmoting ofof equaequalliityty − StrongStrong andand sussustaitainanablblee devedevellopmeopmentnt − EnvEnviironmeronmentalntal manamanagemegementnt whiwhicchh fosfostersters devdevelelopopmentment − SpecSpeciialal aspeaspectscts ofof dedevelveloopmenpmentt • StrenStrengtheninggthening ofof succsuccessfulessful casescases Index • WWhhaatt isis mmeaeanntt byby ththee PPaacciifificc RRegegiioon?n? • Why have a policy for the Pacific? • How is the policy for the Pacific developed? • What does the strategy consist of? • A vision combined with strategic objectives • A role for the Pacific within the National Development Plan − Democratic policy with socially integrated assistance − Poverty reduction and promoting of equality − Strong and sustainable development − Environmental management -

Un Humanitarian Situation Room - Colombia Report August 2004

UN HUMANITARIAN SITUATION ROOM - COLOMBIA REPORT AUGUST 2004 I. NATIONAL CONTEXT • As a response to the serious humanitarian crisis suffered by the communities along the San Juan River (Chocó), between August 21st and 24th a joint mission was conducted in order to observe the conditions in the area. This zone has been impacted by increased conflict over the past several months. As mission included participation by the Ombudsman’s Chocó Regional Office, the Regional Ombudsman’s Office, DASALUD – Chocó, the SSN Chocó Regional office, the local ombudsman of Istmina, the Mayor’s Office and the local ombudsman of Medio San Juan, along with the Diocese of Istmina-Tadó. There was support and accompaniment offered by representatives from UNHCR, OCHA and CODHES. The mission calculated that due to confrontations, no fewer than 1,376 persons were displaced to the municipal seats of Istmina and Medio San Juan. Also, in addition to the 155 families (640 persons) already registered in SUR by SSN, the mission received information from another 149 families (606 persons) not registered in SUR who were displaced from San Miguel and Salado-Isla de Cruz, to Bebedó, Chambacú, Dipurdú, Paimadó, Puerto Murillo and Las Quebradas. There were an undetermined number of families who still remain behind, living along rivers and in mountainous areas. The mission confirmed that the blockade has been ongoing for more than two months and was put in place by armed groups. The blockade obstructs the free movement of persons and the transport of foodstuffs and traditional products that are normally acquired in Istmina municipality. This situation has impacted local health conditions, food security and education services for all of these communities, with a particularly harsh impact among children, since the blockade also affects food programs for local schools. -

Bogotá D.C., 19 De Julio De 2019 Doctora Nancy Patricia Gutierrez

Bogotá D.C., 19 de julio de 2019 Doctora Nancy Patricia Gutierrez Ministra del Interior Secretaría Técnica de la Comisión Intersectorial para la Respuesta rápida a las Alertas Tempranas (CIPRAT) Carrera 8 No. 12 B – 31 Bogotá D.C. Referencia: ALERTA TEMPRANA N°031-19, de INMINENCIA, debido al elevado riesgo que afrontan las poblaciones afrocolombianas e indígenas de Chambacú, San Agustín, Buenas Brisas, Cañaveral, Teatino, Loma Chupey, Marqueza, Santa Rosa, Tanandó, Sipí cabecera municipal, Barraconcito, Barrancón, Charco Largo la Unión, Charco Hondo del Consejo Comunitario General del San Juan - ACADESAN y el Resguardo indígena de Sanadoncito en el municipio de Sipí y de Cajón, Santa Barbará, Torra de (ACADESAN), El Tigre, Juntas del Tamaná, Irabubú, Sesego, Curundó, Santa María de Urubará, Nóvita Cabecera municipal, los consejos locales que integran el Consejo Comunitario Mayor de Nóvita - COCOMAN, y el Resguardo indígena de Sabaletera San Onofre el Tigre, en el municipio de Nóvita (Chocó). Respetada Ministra del Interior: De manera atenta, y de conformidad con lo dispuesto en el Decreto 2124 de 20171, me permito remitir a su Despacho la presente Alerta Temprana de Inminencia debido al elevado riesgo que afrontan las poblaciones afrocolombianas e indígenas de San Agustín, Buenas Brisas, Cañaveral, Teatino, Loma Chupey, Marqueza, Santa Rosa, Tanandó, Sipí cabecera municipal, Barraconcito, Barrancón, Charco Largo la Unión, Charco Hondo y el Resguardo de Sanadoncito en Sipí y de Cajón, El Tigre, Juntas del Tamaná, Irabubú, Curundó, Santa María de Urubará, Nóvita Cabecera municipal, los consejos locales que integran el Consejo Comunitario Mayor de Nóvita - COCOMAN, y el Resguardo indígena de Sabaletera San Onofre el Tigre, en el municipio de Nóvita (Chocó). -

Contexto Territorial De Chocó

Chocó y sus Determinantes Sociales Contexto territorial de Chocó • Departamento con 30 municipios • Dividido en 5 regiones así: 1. Darién 2. Medio San Juan 3. Atrato 4. Pacifico Norte 5. Pacifico sur Fuente: Instituto Geográfico Agustín Codazzi Distribución de los municipios por extensión territorial, Chocó 2012 Departamento del Chocó, Extensión territorial por municipios en km2 Extensión total en KM2 Extensión total en KM2 Municipio Municipio Extensión Porcentaje Extensión Porcentaje Riosucio 7046 15,1 Nuquí 1033 2,2 Litoral del San Juan 3756 8,1 Bahía Solano 976 2,1 Bajo Baudó 3630 7,8 San José del Palmar 940 2,0 Bojaya 3546 7,6 El Carmen de Atrato 931 2,0 Carmen del Darién 3197 6,9 Acandí 869 1,9 Quibdó 3075 6,6 Lloró 841 1,8 Istmina 2000 4,3 Bagadó 770 1,7 Medio Atrato 1842 4,0 Río Quito 700 1,5 Alto Baudó 1532 3,3 Condoto 626 1,4 Medio Baudó 1386 3,0 Medio San Juan 620 1,3 Juradó 1353 2,9 Tadó 576 1,2 Unguía 1307 2,8 Atrato 415 0,9 Sipí 1274 2,7 Cantón del San Pablo 379 0,8 Nóvita 1158 2,5 Cértegui 301 0,7 Río Iro 304 0,7 Unión Panamericana 147 0,3 CHOCÓ 46530 100 Fuente: IGAC - Instituto geográfico Agustín Codazzi Densidad de viviendas por kilómetro cuadrado, Chocó 2005 Fuente: Departamento Administrativo Nacional de Estadísticas - DANE Población cabecera Población Grado de Población resto Municipios municipalPoblación por área de residencia,total urbanización 2014 % Población % Población % Quibdó 107.136 92,7 8.381 7,3 115.517 92,7 Istmina 19.942 79,2 5.241 20,8 25.183 79,2 Condoto 10.193 70,3 4.297 29,7 14.490 70,3 Tadó 12.187 -

Targeting Civilians in Colombia's Internal Armed

‘ L E A V E U S I N P E A C E ’ T LEAVE US IN A ‘ R G E T I N G C I V I L I A N S PEA CE’ I N C O TARG ETING CIVILIANS L O M B I A IN COL OM BIA S INTERNAL ’ S ’ I N T E R ARMED CONFL IC T N A L A R M E D C O N F L I C ‘LEAVE US IN PEACE’ T TARGETING CIVILIANS IN COLOMBIA ’S INTERNAL ARMED CONFLICT “Leave us in peace!” – Targeting civilians in Colombia’s internal armed conflict describes how the lives of millions of Colombians continue to be devastated by a conflict which has now lasted for more than 40 years. It also shows that the government’s claim that the country is marching resolutely towards peace does not reflect the reality of continued A M violence for many Colombians. N E S T Y At the heart of this report are the stories of Indigenous communities I N T decimated by the conflict, of Afro-descendant families expelled from E R their homes, of women raped and of children blown apart by landmines. N A The report also bears witness to the determination and resilience of T I O communities defending their right not to be drawn into the conflict. N A L A blueprint for finding a lasting solution to the crisis in Colombia was put forward by the UN more than 10 years ago. However, the UN’s recommendations have persistently been ignored both by successive Colombian governments and by guerrilla groups. -

Codificación De Municipios Por Departamento

Código Código Municipio Departamento Departamento Municipio 05 001 MEDELLIN Antioquia 05 002 ABEJORRAL Antioquia 05 004 ABRIAQUI Antioquia 05 021 ALEJANDRIA Antioquia 05 030 AMAGA Antioquia 05 031 AMALFI Antioquia 05 034 ANDES Antioquia 05 036 ANGELOPOLIS Antioquia 05 038 ANGOSTURA Antioquia 05 040 ANORI Antioquia 05 042 ANTIOQUIA Antioquia 05 044 ANZA Antioquia 05 045 APARTADO Antioquia 05 051 ARBOLETES Antioquia 05 055 ARGELIA Antioquia 05 059 ARMENIA Antioquia 05 079 BARBOSA Antioquia 05 086 BELMIRA Antioquia 05 088 BELLO Antioquia 05 091 BETANIA Antioquia 05 093 BETULIA Antioquia 05 101 BOLIVAR Antioquia 05 107 BRICEÑO Antioquia 05 113 BURITICA Antioquia 05 120 CACERES Antioquia 05 125 CAICEDO Antioquia 05 129 CALDAS Antioquia 05 134 CAMPAMENTO Antioquia 05 138 CAÑASGORDAS Antioquia 05 142 CARACOLI Antioquia 05 145 CARAMANTA Antioquia 05 147 CAREPA Antioquia 05 148 CARMEN DE VIBORAL Antioquia 05 150 CAROLINA Antioquia 05 154 CAUCASIA Antioquia 05 172 CHIGORODO Antioquia 05 190 CISNEROS Antioquia 05 197 COCORNA Antioquia 05 206 CONCEPCION Antioquia 05 209 CONCORDIA Antioquia 05 212 COPACABANA Antioquia 05 234 DABEIBA Antioquia 05 237 DON MATIAS Antioquia 05 240 EBEJICO Antioquia 05 250 EL BAGRE Antioquia 05 264 ENTRERRIOS Antioquia 05 266 ENVIGADO Antioquia 05 282 FREDONIA Antioquia 05 284 FRONTINO Antioquia 05 306 GIRALDO Antioquia 05 308 GIRARDOTA Antioquia 05 310 GOMEZ PLATA Antioquia 05 313 GRANADA Antioquia 05 315 GUADALUPE Antioquia 05 318 GUARNE Antioquia 05 321 GUATAPE Antioquia 05 347 HELICONIA Antioquia 05 353 HISPANIA Antioquia -

ECONOMIC 10 November 1962 ENGLISH ORIGINAL: ENGLISH/SPANISH

UNITED NATI general E/CN.12/618 ECONOMIC 10 November 1962 ENGLISH ORIGINAL: ENGLISH/SPANISH MiMiMMiMiummMMHNtnimiHiimMMitHiiiiitMtiHihnmHHMtiimmiiHMHMiiiiini ECONOMO COMMISSION FOR LATIN AMERICA SOME ASPECTS OF POPULATION GROWTH IN COLOMBIA Prepared by the secretariat of the Economic Commission for Latin America E/CN,12/618 Page iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Sage Introduction. ............ ...»c..... 1 Population Estimates ..aoo.........•<>.o»... <,......... 3 1. Total population growth» «••.«•••»•a...*. 3 (a) The censuses of 1938 and 1.951 3 (b) Recent population growth in Ecuador, Mexico and 'Venezuela,, ........a...,,,», ...*<>«••...,, .,,,*«» 7 (c) Birth rates and death rates in Colombia 8 (d) Estimated population growth, 1945-70. ... 11 2. Population growth by departments ..... 14 (a) Growth of departmental populations according to census es osoo. 14 (b) Effects of migration 16 (c) Natural increase0.o * 21 (d) Population estimates for departments, 1945-70 23 3. Urban and rural populations,., 25 (a) Census definitions* 25 (b) The projection, 27 (c) Population of towns of various sizes* 29 (d) Urban and rural population by departments,,... • 34 II, Implications for education, manpower and housing,,..»., 41 1, Population and primary education0„ 9009 oe..'...«........... 41 (a) Children enrolled in primary schools.......... 41 (b) Number of children of proper primary school age...... 49 (c) Primary education: future requirements».,,..,,,...... 57 (d) Regional distribution of school children and school enrolment. o........... 62 (e) Educational level0.»....,.,.,........................ 66 (f) Literacy... 69 /2. Population and E/CN.12/618 Page iv £äge 2o Population and manpowers,..., <,.......» » 76 (a) Difficulty of study 76 (b) Economic activity of the population in 1951...* 77 (c) Reported economic activity of the population in 1938.... 80 (d) Effects of urbanization.. -

Por Medio De La Cual Se Asigna Al IGAC, Como Gestor Catastral Por

RESOLUCIÓN 45 DEL 20 DE ENERO DE 2021 “Por medio de la cual se asigna al IGAC, como gestor catastral por excepción, el prefijo y las series del Código Homologado de Identificación Predial (CH) en los municipios a su cargo para los predios registrados en el Sistema Nacional Catastral – SNC.” LA DIRECTORA GENERAL DEL INSTITUTO GEOGRÁFICO AGUSTÍN CODAZZI En uso de las facultades que le confieren el numeral 7 del artículo 14 del Decreto 2113 de 1992, el numeral 1 del artículo 6 del Decreto 208 de 2004, y C O N S I D E R A N D O: Que de acuerdo con el CONPES 3958 de 2019, la interrelación del catastro con el registro se ha identificado como una necesidad recurrente que busca facilitar el intercambio, unificación, mantenimiento y acceso a la información, tanto catastral como registral, por parte de los actores del proceso. Que el artículo 79 de la Ley 1955 del 25 de mayo de 2019, establece que, la gestión catastral es un servicio público entendido como un conjunto de operaciones técnicas y administrativas orientadas a la adecuada formación, actualización, conservación y difusión de la información catastral, así como los procedimientos del enfoque catastral multipropósito que sean adoptados y, adicionalmente, señala el marco general de su desarrollo. Que el artículo 79 de la Ley 1955 del 25 de mayo de 2019, establece que, el Instituto Geográfico Agustín Codazzi (IGAC) será la máxima autoridad catastral nacional y prestador por excepción del servicio público de catastro, en ausencia de gestores catastrales habilitados. Que el artículo 2.2.2.1.1. -

Hugo Salazar Valdés: La Problemática Del Medio Ambiente En La Poesía Afro-Colombiana Del Pacífico Alain Lawo-Sukam Georgia Southern University

Hipertexto 6 Verano 2007 pp. 37-50 Hugo Salazar Valdés: la problemática del medio ambiente en la poesía afro-colombiana del Pacífico Alain Lawo-Sukam Georgia Southern University Hipertexto “Hugo Salazar Valdés constituye hoy por hoy en Colombia el representante de la poesía chocoana” (Jaime Mejía Duque) a poesía afro-colombiana es poco estudiada, a diferencia de la prosa que ha L captado la atención de muchos pioneros y críticos de la literatura afro- colombiana como Richard Jackson, Marvin Lewis, Laurence Prescott y Miriam DeCosta-Willis entre otros.1 Dicha poesía constituye un espacio discursivo en que los poetas plasman con eficacia y facilidad sus experiencias de vida y su concepción del mundo, con la aplicación del ritmo, la imitación de los sonidos o instrumentos musicales que marcan la africanidad de la costa y del valle. En este contexto, la poesía no constituye un mero género ficticio sino una de las herramientas de estudios socioculturales del afro-hispano. Por medio del arte poético, el escritor afro-hispano trata de descifrar y de revelar a la humanidad los elementos que definen su existencia y la de su pueblo. Es a la vez una poesía personal y colectiva. Entre los poetas afro-colombianos destaca la figura del prolífico Hugo Salazar Valdés (1924-1996). Poco conocido en la arena literaria, Salazar Valdés logra dar una dimensión especial a la literatura del Pacífico colombiano con su producción poética. Su primer éxito literario vino en 1948 cuando publicó sus poemarios iniciales Sol y lluvia y Carbones en el alba. Su pasión por la poesía 1 Marvin Lewis es uno de los pocos críticos que estudian la poesía afro-hispana.