A Novel Approach to Tradition: Torres Strait Islanders and Ion Idriess

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

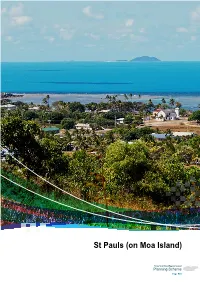

St Pauls (On Moa Island) - Local Plan Code

7.2.13 St Pauls (on Moa Island) - local plan code Part 7: Local Plans St Pauls (on Moa Island) St Pauls (on Moa Island) Torres Strait Island Regional Council Planning Scheme Page 523 Torres Strait Island Regional Council Planning Scheme Page 524 Part 7: Local Plans St Pauls (on Moa Island) Papua New Guinea Saibai Ugar Boigu Stephen Island Erub Dauan Darnley Island Masig Yorke Island Iama Mabuyag Yam Island Mer Poruma Murray Island Coconut Island Badu Kubin Moa SStt PPaulsauls Warraber Sue Island Keriri Hammond Island Mainland Australia Mainland Australia Torres Strait Island Regional Council Planning Scheme Page 525 Editor’s Note – Community Snapshot Location Topography and Environment • St Pauls is located on the eastern side of Moa • Moa Island, like other islands in the group, is Island, which is part of the Torres Strait inner and a submerged remnant of the Great Dividing near western group of islands. St Paul’s nearest Range, now separated by sea. The island neighbour is Kubin, which is located on the comprises of largely of rugged, open forest and south-western side of Moa Island. Approximately is approximately 17km in diameter at its widest 15km from the outskirts of St Pauls. point. • Native flora and fauna that have been identified Population near St Pauls include fawn leaf nosed bat, • According to the most recent census, there were grey goshawk, emerald monitor, little tern, 258 people living in St Pauls as at August 2011, red goshawk, radjah shelduck, lipidodactylus however, the population is highly transient and primilus, bare backed fruit bat, torresian tube- this may not be an accurate estimate. -

How Torres Strait Islanders Shaped Australia's Border

11 ‘ESSENTIALLY SEA‑GOING PEOPLE’1 How Torres Strait Islanders shaped Australia’s border Tim Rowse As an Opposition member of parliament in the 1950s and 1960s, Gough Whitlam took a keen interest in Australia’s responsibilities, under the United Nations’ mandate, to develop the Territory of Papua New Guinea until it became a self-determining nation. In a chapter titled ‘International Affairs’, Whitlam proudly recalled his government’s steps towards Papua New Guinea’s independence (declared and recognised on 16 September 1975).2 However, Australia’s relationship with Papua New Guinea in the 1970s could also have been discussed by Whitlam under the heading ‘Indigenous Affairs’ because from 1973 Torres Strait Islanders demanded (and were accorded) a voice in designing the border between Australia and Papua New Guinea. Whitlam’s framing of the border issue as ‘international’, to the neglect of its domestic Indigenous dimension, is an instance of history being written in what Tracey Banivanua- Mar has called an ‘imperial’ mode. Historians, she argues, should ask to what extent decolonisation was merely an ‘imperial’ project: did ‘decolonisation’ not also enable the mobilisation of Indigenous ‘peoples’ to become self-determining in their relationships with other Indigenous 1 H. C. Coombs to Minister for Aboriginal Affairs (Gordon Bryant), 11 April 1973, cited in Dexter, Pandora’s Box, 355. 2 Whitlam, The Whitlam Government, 4, 10, 26, 72, 115, 154, 738. 247 INDIGENOUS SELF-determinatiON IN AUSTRALIA peoples?3 This is what the Torres Strait Islanders did when they asserted their political interests during the negotiation of the Australia–Papua New Guinea border, though you will not learn this from Whitlam’s ‘imperial’ account. -

TORRES STRAIT REGIONAL AUTHORITY Docip ARCHIVES

TORRES STRAIT REGIONAL AUTHORITY doCip ARCHIVES 19'" SESSION OF THE WORKING GROUP ON INDIGENOUS POPULATIONS 23-27 JULY, 2001 GENEVA ADDRESS BY THE CHAIRPERSON OF THE TORRES STRAIT REGIONAL AUTHORITY MR TERRY WAIA Madame Chair Distinguished Members of the Working Group Minister Ruddock Indigenous Members of the World Ladies and Gentlemen Once again, this is indeed an honour and a pleasure. To meet with all of you here today who have travelled from every comer of the globe to share your experiences, hopes and aspirations, is not only a rewarding experience but is most encouraging as we continue to persevere towards our many and varied goals. My name is Terry Waia and I stand here today as a representative of the people of the Torres Strait Islands in Australia. This is the second time that I have had the privilege to represent my people at a session of this Working Group and I welcome this opportunity to inform you of the progress we are making in our region. The Torres Strait is a unique and beautiful part of the world, home for my people, the Torres Strait Islanders. We are of Melanesian origin and our population of approximately 8000 live amongst 17 island communities scattered across a 150km expanse of sea separating mainland Australia from the south coast of Papua New Guinea. In the Torres Strait I hold two key positions, that of Chairperson of Saibai Island, one of the region's northern most islands, and Chairperson of the Torres Strait Regional Authority (TSRA), a Commonwealth Government authority that was established in 1994 by the Parliament of Australia. -

Cultural Heritage Series

VOLUME 4 PART 2 MEMOIRS OF THE QUEENSLAND MUSEUM CULTURAL HERITAGE SERIES 17 OCTOBER 2008 © The State of Queensland (Queensland Museum) 2008 PO Box 3300, South Brisbane 4101, Australia Phone 06 7 3840 7555 Fax 06 7 3846 1226 Email [email protected] Website www.qm.qld.gov.au National Library of Australia card number ISSN 1440-4788 NOTE Papers published in this volume and in all previous volumes of the Memoirs of the Queensland Museum may be reproduced for scientific research, individual study or other educational purposes. Properly acknowledged quotations may be made but queries regarding the republication of any papers should be addressed to the Editor in Chief. Copies of the journal can be purchased from the Queensland Museum Shop. A Guide to Authors is displayed at the Queensland Museum web site A Queensland Government Project Typeset at the Queensland Museum CHAPTER 4 HISTORICAL MUA ANNA SHNUKAL Shnukal, A. 2008 10 17: Historical Mua. Memoirs of the Queensland Museum, Cultural Heritage Series 4(2): 61-205. Brisbane. ISSN 1440-4788. As a consequence of their different origins, populations, legal status, administrations and rates of growth, the post-contact western and eastern Muan communities followed different historical trajectories. This chapter traces the history of Mua, linking events with the family connections which always existed but were down-played until the second half of the 20th century. There are four sections, each relating to a different period of Mua’s history. Each is historically contextualised and contains discussions on economy, administration, infrastructure, health, religion, education and population. Totalai, Dabu, Poid, Kubin, St Paul’s community, Port Lihou, church missions, Pacific Islanders, education, health, Torres Strait history, Mua (Banks Island). -

Appendix a (PDF 85KB)

A Appendix A: Committee visits to remote Aboriginal and Torres Strait communities As part of the Committee’s inquiry into remote Indigenous community stores the Committee visited seventeen communities, all of which had a distinctive culture, history and identity. The Committee began its community visits on 30 March 2009 travelling to the Torres Strait and the Cape York Peninsula in Queensland over four days. In late April the Committee visited communities in Central Australia over a three day period. Final consultations were held in Broome, Darwin and various remote regions in the Northern Territory including North West Arnhem Land. These visits took place in July over a five day period. At each location the Committee held a public meeting followed by an open forum. These meetings demonstrated to the Committee the importance of the store in remote community life. The Committee appreciated the generous hospitality and evidence provided to the Committee by traditional owners and elders, clans and families in all the remote Aboriginal and Torres Strait communities visited during the inquiry. The Committee would also like to thank everyone who assisted with the administrative organisation of the Committee’s community visits including ICC managers, Torres Strait Councils, Government Business Managers and many others within the communities. A brief synopsis of each community visit is set out below.1 1 Where population figures are given, these are taken from a range of sources including 2006 Census data and Grants Commission figures. 158 EVERYBODY’S BUSINESS Torres Strait Islands The Torres Strait Islands (TSI), traditionally called Zenadth Kes, comprise 274 small islands in an area of 48 000 square kilometres (kms), from the tip of Cape York north to Papua New Guinea and Indonesia. -

Card Operated Meter Information

Purchasing a power card for your card-operated meter Power cards are available from the following sales outlets: Community Retail Agent Address Arkai (Kubin) Community T.S.I.R.C. - Kubin KUBIN COMMUNITY, MOA ISLAND QLD 4875 Arkai (Kubin) Community CEQ - Kubin IKILGAU YABY RD, KUBIN VILLAGE, MOA ISLAND QLD 4875 Aurukun Island & Cape 39 KANG KANG RD, AURUKUN QLD 4892 Aurukun Supermarket Aurukun Kang Kang Café 502 KANG KAND RD, AURUKUN QLD 4892 Badu (Mulgrave) Island Badu Hotel 199 NONA ST, BADU ISLAND QLD 4875 Badu (Mulgrave) Island Island & Cape Badu MAIRU ST, BADU ISLAND QLD 4875 Supermarket (Bottom Shop) Badu (Mulgrave) Island J & J Supermarket 341 CHAPMAN ST, BADU ISLAND QLD (Top Shop) 4875 Badu (Mulgrave) Island T.S.I.R.C. - Badu NONA ST, BADU ISLAND QLD 4875 Bamaga Bamaga BP Service AIRPORT RD, BAMAGA QLD 4876 Station Bamaga Cape York Traders 201 LUI ST, BAMAGA QLD 4876 – Bamaga Store Bamaga CEQ – Bamaga 105 ADIDI AT, BAMAGA QLD 4876 Supermarket Boigu (Talbot) Island CEQ – Boigu TOBY ST, BOIGU QLD 4875 Supermarket Boigu (Talbot) Island T.S.I.R.C. - Boigu 66 CHAMBERS ST, BOIGU ISLAND QLD 4875 Darnley Island (Erub) Daido Tavern PILOT ST, DARNLEY ISLAND QLD 4875 Darnley Island (Erub) T.S.I.R.C. - Darnley COUNCIL OFFICE, DARNLEY ISLAND QLD 4875 Dauan Island (Mt CEQ - Dauan MAIN ST, DAUAN ISLAND QLD 4875 Cornwallis) Supermarket Dauan Island (Mt T.S.I.R.C. - Dauan COUNCIL OFFICE, MAIN ST, DAUAN Cornwallis) ISLAND QLD 4875 Doomadgee CEQ – Doomadgee 266 GUNNALUNJA DR, DOOMADGEE QLD Supermarket 4830 Doomadgee Doomadgee 1 GOODEEDAWA RD, DOOMADGEE -

Part 7 Transport Infrastructure Plan

Sea Transport Safety The marine investigation unit of the Australian Transport Safety Bureau (ATSB) was contacted for information pertaining to recent accidents and incidents with large trading vessels in the region. The data provided related to five incidents that occurred after July 1995 and before 2004: a) A man overboard from the vessel Murshidabad in 1996; b) A close quarters situation between the Maersk Taupo and a small dive runabout off Ackers Shoal Beacon in 1997; c) The grounding of the vessel Thebes on Larpent Bank in 1997; d) The grounding of the vessel Dakshineshwar on Larpent Bank in 1997; and e) The grounding of the vessel NOL Amber on Larpent Bank in 1997. Figure 3.7 shows the location of marine accidents that have occurred in northern Queensland in 2004. Figure 3.7 Location of Marine Accidents in Northern Queensland (2004) Source: MSQ: 2005 Torres Strait Transport Infrastructure Plan - Integrated Strategy Report J:\mmpl\10303705\Engineering\Reports\Transport Infrastructure Plan\Transport Infrastructure Plan - Rev I.doc Revision I November 2006 Page 21 Figure 3.8 Existing Ferry Services Torres Strait Transport Ugar (Stephen) Island Infrastructure Plan Papua New Guinea Ferry Routes ° Saibai (Kaumag) Island Dauan Island Erub (Darnley) Island Map 1 - Saibai (Kaumag) Island to Dauan Island 1:200,000 Map 2 - Ugar (Stephen) Island to Erub (Darnley) Island 1:150,000 Hammond Waiben Map 1 Island (Thursday) Island Map 2 Nguruppai (Horn) Island Muralug (Prince of Wales) Island Map 3 Seisia Seisia Map 3 - Thursday Island 1:300,000 -

Cape York Region Islanders #1 Non Freehold Land Tenure Sourced from Department of Resources (QLD) March 2021

141°0'E 142°0'E 143°0'E 144°0'E 145°0'E Buru & Erubam Le Warul Kawa Masig People Ugar (Stephens Claimant application and determination boundary data compiled from NNTT based( Doanrnbloeuyndaries with areas excluded or discrete boundaries of areas being claimed) as To determine whether any areas fall within the external boundary of an application or and Damuth Islanders) #1 data sourced from Department of Resources (Qld) © The State of Queensland foIsr ltahnadt etrhse)y # h1ave been recognised by the Federal Court process. determination, a search of the Tribunal's registers and People portion where their data has been used. Where the boundary of an application has been amended in the Federal Court, the databases is required. Further information is available from the Tribunals website at map shows this boundary rather than the boundary as per the Register of Native Title www.nntt.gov.au or by calling 1800 640 501 Topographic vector data is © Commonwealth of Australia (Geoscience Australia) Claims (RNTC), if a registered application. © Commonwealth of Australia 2021 Gebara 2006. The applications shown on the map include: Cape York Region Islanders #1 Non freehold land tenure sourced from Department of Resources (QLD) March 2021. - registered applications (i.e. those that have complied with the registration test), The Registrar, the National Native Title Tribunal and its staff, members and agents - new and/or amended applications where the registration test is being applied, and the Commonwealth (collectively the Commonwealth) accept no liability and give As part Yofa mthe transitional provisions of the amended Native Title Act in 1998, all - unregistered applications (i.e. -

The Torres Strait Islands Collection at the Australian Museum

TECHNICAL REPORTS OF THE AUSTRALIAN MUSEUM The Torres Strait Islands Collection at the Australian Museum Stan Florek 2005 dibi-dibi, breast ornament, Mer, AM E.17346 Florek • Torres Strait Islands Collection A M AUSTRALIAN MUSEUM Technical Reports of the Australian Museum may be purchased at the Australian Museum Shop · www.amonline.net.au/shop/ or viewed online · www.amonline.net.au/publications/ Technical Reports of the Australian Museum Number 19 TECHNICAL REPORTS OF THE AUSTRALIAN MUSEUM Director: Frank Howarth The Australian Museum’s mission is to research, interpret, communicate and apply understanding of the environments The Editor: Shane F. McEvey and cultures of the Australian region to increase their long- term sustainability. The Museum has maintained the highest standards of scholarship in these fields for more Editorial Committee: than 175 years, and is one of Australia’s foremost publishers of original research in zoology, anthropology, Chair: G.D.F. Wilson (INVERTEBRATE ZOOLOGY) archaeology, and geology. The Records of the Australian Museum (ISSN 0067- M.S. Moulds (INVERTEBRATE ZOOLOGY) 1975) publishes the results of research on Australian S.F. McEvey (EX OFFICIO) Museum collections and of studies that relate in other ways J.M. Leis (VERTEBRATE ZOOLOGY) to the Museum’s mission. There is an emphasis on S. Ingleby (VERTEBRATE ZOOLOGY) Australasian, southwest Pacific and Indian Ocean research. I.T. Graham (GEOLOGY) The Records is released annually as three issues of one volume, volume 56 was published in 2004. Monographs D.J. Bickel (INVERTEBRATE ZOOLOGY) are published about once every two years as Records of V.J. Attenbrow (ANTHROPOLOGY) the Australian Museum, Supplements. -

1998 ANNUAL REPORT 60011 Cover 16/11/98 2:43 PM Page 2

TORRES STRAIT REGIONAL AUTHORITY 1997~1998 ANNUAL REPORT 60011 Cover 16/11/98 2:43 PM Page 2 ©Commonwealth of Australia 1998 ISSN 1324–163X This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from the Torres Strait Regional Authority (TSRA). Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction rights should be directed to the Public Affairs Officer, TSRA, PO Box 261, Thursday Island, Queensland 4875. The artwork on the front cover was designed by Torres Strait Islander artist, Alick Tipoti. Annual Report 1997~98 PUPUA NEW GUINEA SAIBAI ISLAND (Kaumag Is) BOIGU ISLAND UGAR (STEPHEN) ISLAND DAUAN ISLAND TORRES STRAIT DARNLEY ISLAND YAM ISLAND MASIG (YORKE) ISLAND MABUIAG ISLAND MER (MURRAY) ISLAND BADU ISLAND PORUMA (COCONUT) ISLAND ST PAULS WARRABER (SUE) ISLAND KUBIN MOA ISLAND HAMMOND ISLAND THURSDAY ISLAND (Port Kennedy, Tamwoy) HORN ISLAND PRINCE OF WALES ISLAND SEISIA BAMAGA CAPE YORK TORRES STRAIT REGIONAL AUTHORITY © Commonwealth of Australia 1998 This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from the Torres Strait Regional Authority (TSRA). Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction rights should be directed to the Public Affairs Officer, TSRA, PO Box 261, Thursday Island, Queensland 4875. The artwork on the front cover was designed by Torres Strait Islander artist, Alick Tipoti. TORRES STRAIT REGIONAL AUTHORITY Senator the Hon. John Herron Minister for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Affairs Suite MF44 Parliament House CANBERRA ACT 2600 Dear Minister In accordance with section 144ZB of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission Act 1989, I am delighted to present you with the fourth Annual Report of the Torres Strait Regional Authority (TSRA). -

Past Visions, Present Lives: Sociality and Locality in a Torres Strait Community

Past Visions, Present Lives: sociality and locality in a Torres Strait community. Thesis submitted by Julie Lahn BA (Hons) (JCU) November 2003 for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the School of Anthropology, Archaeology and Sociology Faculty of Arts, Education and Social Sciences James Cook University Statement of Access I, the undersigned, the author of this thesis, understand that James Cook University will make it available for use within the University Library and, by microfilm or other means, allow access to users in other approved libraries. All users consulting this thesis will have to sign the following statement: In consulting this thesis I agree not to copy or closely paraphrase it in whole or in part without the written consent of the author; and to make proper public written acknowledgment for any assistance that I have obtained from it. Beyond this, I do not wish to place any restriction on access to this thesis. _________________________________ __________ Signature Date ii Statement of Sources Declaration I declare that this thesis is my own work and has not been submitted in any form for another degree or diploma at any university or other institution of tertiary education. Information derived from the published or unpublished work of others has been acknowledged in the text and a list of references is given. ____________________________________ ____________________ Signature Date iii Acknowledgments My main period of fieldwork was conducted over fifteen months at Warraber Island between July 1996 and September 1997. I am grateful to many Warraberans for their assistance and generosity both during my main fieldwork and subsequent visits to the island. -

A Draft for the Assignment

THE MISSIONARY WOMEN IN THE INLAND OF AUSTRALIA AND THE AUSTRALIAN INLAND MISSION AS REPRESENTED IN BETH BECKETT’S LIFE MEMOIR Evi Eliyanah ([email protected]) Universitas Negeri Malang, Indonesia Abstract: This article looks at the gender dimension of religious missions adminis- tered by the Presbyterian Church in the inland Australia as represented in Beth Beck- ett’s life memoir written in 1947-1955. It is aimed at obtaining general ideas on the involvement of women, as the wives of missionaries, Focusing on the experience of Beth Beckett, it argues that her position as a wife of a missionary is problematic: on the one hand she did transgress the traditional idea of staying-home wife by choosing to travel along with her husband, but at the same time, she was still bound by the domestic side of the job. Key words: Australian Inland Mission, Beth Beckett, Memoir, Gender This article critically examines the gender dimension of the missions ad- ministered by the Presbyterian Church in the inland of Australia, known as the Australian Inland Mission (AIM). Looking at the role of women, especially the missionary wives in the missionary process: the roles they took up and their agency in being involved in the mission, the essay focuses on the experience of Beth Becket, an ex-AIM-nurse married to a patrol padre. Critically analyzing her memoirs, written in 1947-1955, the article offers general ideas on the in- volvement of women, as the wives of missionaries, in the mission field during the mid twentieth century. Bringing together the thoughts and ideas poured in the writings on women and the mission enterprise in the British colonies, the 107 108 TEFLIN Journal, Volume 21, Number 2, August 2010 memoirs will be scrutinized in terms of women agency and women’s specific roles on the mission.