Westerly Magazine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vision and Transition Strategy for A

Vision and Transition Strategy for a Water Sensitive Greater Perth CRCWSC Integrated Research Project 1: Water Sensitive City Visions and Transition Strategies 2 | Vision and Transition Strategy for a Water Sensitive Greater Perth Vision and Transition Strategy for a Water Sensitive Greater Perth IRP1 WSC Visions and Transition Strategies IRP1-4-2018 Authors Katie Hammer1,2, Briony Rogers1,2, Chris Chesterfield2 1 School of Social Sciences, Monash University 2 CRC for Water Sensitive Cities © 2018 Cooperative Research Centre for Water Sensitive Cities Ltd. This work is copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of it may be reproduced by any process without written permission from the publisher. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction rights should be directed to the publisher. Publisher Cooperative Research Centre for Water Sensitive Cities Level 1, 8 Scenic Blvd, Clayton Campus Monash University Clayton, VIC 3800 p. +61 3 9902 4985 e. [email protected] w. www.watersensitivecities.org.au Date of publication: August 2018 An appropriate citation for this document is: Hammer, K., Rogers, B.C., Chesterfield, C. (2018) Vision and Transition Strategy for a Water Sensitive Greater Perth. Melbourne, Australia: Cooperative Research Centre for Water Sensitive Cities. This report builds directly on “Shaping Perth as a Water Sensitive City: Outcomes and perspectives from a participatory process to develop a vision and strategic transition framework”, which was the output of a precursor CRCWSC project, A4.2 Mapping water sensitive city scenarios. Acknowledgements The authors would like to thank the Water Sensitive Transition Network for their ongoing enthusiasm and commitment to the water sensitive city agenda in Perth. -

Street Tree Master Plan Version 2 - September 2005

City of Wanneroo Street Tree Master Plan Version 2 - September 2005 Version No. Detail List of Revisions Date Authorised by Version 1 - Aug’04 As Presented by Arbor Vitae 10 August Council and approved by Council 2004 Version 2 - Sept’05 Full Internal Review - As • Addition of List of Common Names (Appendix C) September Council/Rob K adopted at City of Wanneroo • Addition of the following tree species: 2005/August Council Meeting held on 20 1. Brachychiton gregorii 2006 September 2005 2. Callistemon “Kings Park Special” 3. Eucalyptus melliodora 4. Eucalyptus “torwood” 5. Liquidambar styraciflua 6. Melaleuca ericifolia 7. Prunus x blireana 8. Pyrus calleryana Includes revisions to Landscape Character Unit Tree Lists and Appendix D (formerly Appendix C) Plant Information Fact Sheets. • Modifications to Plant Information Fact Sheets including additional photos, more information on longevity, and amendments to the following: Olea europea (more information), correction of all “Headings” formerly spelt “Habitat” to “Habit” and spelling correction to Araucaria heterophylla. • Reference to “City of Wanneroo Recommended Climber Groundcover and Shrub Species list in Executive Summary and Appendix E. • Modification to Figure 26 – More Fire Resistant native trees. Table of Contents 1.0 Introduction...........................................................................................................................................................................................6 1.1 Requirements of Trees, the Public and the City of Wanneroo.............................................................................................................7 -

Classification of Arid & Semi-Arid Areas

Classification of Arid & Semi-Arid Areas: A Case Study in Western Australia Guy Leech Abstract Arid and semi-arid environments present challenges for ecosystems and the human activities within them. Climate classifications are one method of understanding the climate of these regions, giving regional- scale insight into parameters such as temperature and precipitation. This essay qualitatively compares the application of four different climate classification schemes (Köppen-Trewartha, Guetter-Kutzbach, De Martonne and Erinç) to a transect across Western Australia. The classification schemes show a distinct climatic gradient from the wet coast to the dry continental interior, with the most pronounced gradient located near the coast. Strong agreement is found between weather stations and classifications for wet and dry years, indicating that the weather systems on the coast also govern weather inland. Historically wet and dry periods, as well as long-term drying trends were also identified for the coastal regions, which could affect the livelihoods of many people. A long-term drying trend is also evident at Kalgoorlie- Boulder, the most arid, inland town. These results show that climate classifications can identify major trends and shifts in climate on a decadal or yearly basis, and it is hoped that they will become more widely used for this form of analysis. Introduction Arid and semi-arid environments make up a large portion of the Earth’s surface (Figure 1), and present challenges for human ecosystems located within them. These regions are generally defined as having low average rainfall, often associated with high temperatures, which impose fundamental limits on animal and plant populations, and on human activities such as agriculture (CSIRO 2011, Ludwig & Asseng 2006, Ribot et al. -

A Draft for the Assignment

THE MISSIONARY WOMEN IN THE INLAND OF AUSTRALIA AND THE AUSTRALIAN INLAND MISSION AS REPRESENTED IN BETH BECKETT’S LIFE MEMOIR Evi Eliyanah ([email protected]) Universitas Negeri Malang, Indonesia Abstract: This article looks at the gender dimension of religious missions adminis- tered by the Presbyterian Church in the inland Australia as represented in Beth Beck- ett’s life memoir written in 1947-1955. It is aimed at obtaining general ideas on the involvement of women, as the wives of missionaries, Focusing on the experience of Beth Beckett, it argues that her position as a wife of a missionary is problematic: on the one hand she did transgress the traditional idea of staying-home wife by choosing to travel along with her husband, but at the same time, she was still bound by the domestic side of the job. Key words: Australian Inland Mission, Beth Beckett, Memoir, Gender This article critically examines the gender dimension of the missions ad- ministered by the Presbyterian Church in the inland of Australia, known as the Australian Inland Mission (AIM). Looking at the role of women, especially the missionary wives in the missionary process: the roles they took up and their agency in being involved in the mission, the essay focuses on the experience of Beth Becket, an ex-AIM-nurse married to a patrol padre. Critically analyzing her memoirs, written in 1947-1955, the article offers general ideas on the in- volvement of women, as the wives of missionaries, in the mission field during the mid twentieth century. Bringing together the thoughts and ideas poured in the writings on women and the mission enterprise in the British colonies, the 107 108 TEFLIN Journal, Volume 21, Number 2, August 2010 memoirs will be scrutinized in terms of women agency and women’s specific roles on the mission. -

Irish in Australia

THE IRISH IN AUSTRALIA. BY THE SAME AUTHOR. AN AUSTRALIAN CHRISTMAS COLLECTIONt A Series of Colonial Stories, Sketches , and Literary Essays. 203 pages , handsomely bound in green and gold. Price Five Shillings. A VERYpleasant and entertaining book has reached us from Melbourne. The- author, Mr. J. F. Hogan, is a young Irish-Australian , who, if we are to judge- from the captivating style of the present work, has a brilliant future before him. Mr. Hogan is well known in the literary and Catholic circles of the Australian Colonies, and we sincerely trust that the volume before us will have the effect of making him known to the Irish people at home and in America . Under the title of " An Australian Christmas Collection ," Mr. Hogan has republished a series of fugitive writings which he had previously contributed to Australian periodicals, and which have won for the author a high place in the literary world of the. Southern hemisphere . Some of the papers deal with Irish and Catholic subjects. They are written in a racy and elegant style, and contain an amount of highly nteresting matter relative to our co-religionists and fellow -countrymen under the Southern Cross. A few papers deal with inter -Colonial politics , and we think that home readers will find these even more entertaining than those which deal more. immediately with the Irish element. We have quoted sufficiently from this charming book to show its merits. Our readers will soon bear of Mr. Hogan again , for he has in preparation a work on the "Irish in Australia," which, we are confident , will prove very interesting to the Irish people in every land. -

Lord Mayor and Councillors, NOTICE IS HEREBY GIVEN That the Next

Lord Mayor and Councillors, NOTICE IS HEREBY GIVEN that the next meeting of the Works and Urban Development Committee will be held in Committee Room 1, Ninth Floor, Council House, 27 St Georges Terrace, Perth on Tuesday, 27 September 2016 at 5.30pm. Yours faithfully MARTIN MILEHAM CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER 22 September 2016 Committee Members: Members: 1st Deputy: 2nd Deputy: Cr Limnios (Presiding Member) The Lord Mayor Cr Harley Cr Chen Cr McEvoy Please convey apologies to Governance on 9461 3250 or email [email protected] EMERGENCY GUIDE Council House, 27 St Georges Terrace, Perth The City of Perth values the health and safety of its employees, tenants, contractors and visitors. The guide is designed for all occupants to be aware of the emergency procedures in place to help make an evacuation of the building safe and easy. BUILDING ALARMS KNOW Alert Alarm and Evacuation Alarm. YOUR EXITS ALERT ALARM beep beep beep All Wardens to respond. Other staff and visitors should remain where they are. EVACUATION ALARM/PROCEDURES whoop whoop whoop On hearing the Evacuation Alarm or on being instructed to evacuate: 1. Move to the floor assembly area as directed by your Warden. 2. People with impaired mobility (those who cannot use the stairs unaided) should report to the Floor Warden who will arrange for their safe evacuation. 3. When instructed to evacuate leave by the emergency exits. Do not use the lifts. 4. Remain calm. Move quietly and calmly to the assembly area in Stirling Gardens as shown on the map below. Visitors must remain in the company of City of Perth staff members at all times. -

Bludgers in Grass Castles

Bludgers in Grass Castles Native Title & the Unpaid Debts of the Pastoral Industry Martin Taylor 2 BLUDGERS IN GRASS CASTLES Contents Introduction ..........................................................................................3 Kings in grass castles — 3 l The ‘threat’ of native title — 3 l The powers behind the pastoralists — 5 l Politicians help themselves — 6 l Reconciliation: all talk, no action? — 6 l The aim of this essay — 7 Pastoralism in Queensland: A (Brief) History ................................8 Marauding nomads invade — 8 l Resistance to invasion — 8 l Aboriginal labour pool — 9 l The pool dries up — 11 l Pastoral colonialiism around the world — 12 l The balance sheet — 13 Crimes Ignored ..................................................................................16 Stolen land — 16 l Destruction of Aboriginal heritage — 17 l Genocide and racism — 18 l Lands laid waste — 19 l Poison — 20 l Anti-environmentalism — 21 Bills Overdue .....................................................................................23 Back pay — 23 l Aboriginal pastures — 23 l Direct public subsidies — 24 l Indirect subsidies: infrastructure and token rents — 25 The Future of the Pastoral Industry ..............................................27 Leaner and meaner — 27 l Is the pastoral zone relevant? — 28 l A new pastoral economy? — 29 l Conclusion — 29 Notes ...................................................................................................31 First printed 1997; reprinted 1998 (twice), 2009, 2017 ISBN 978-0-909196-72-1 -

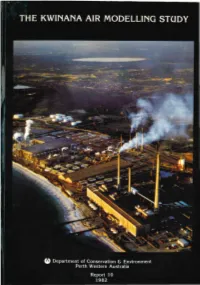

The Kwinana Air Modelling Study

THE KWINANA AIR MODELLING STUDY • !i t .,....... ........ ~ ,; ~ ;, • 1, ' I, 'I I I. I' I ,1 ' .~ , '-.._ l I ' .•"'- ~ ,. - ,· '• ..- ... - Ca) Department of Conservation & Environment Perth Western Australia Report 10 1982 THE KWINANA AIR MODELLING STUDY A study promoted by the Department of Conservation and Environment and the Department of Public Health in co-operation with the Commonwealth Bureau of Meteorology State Energy Commission of Western Australia Western Australian Institute of Technology Murdoch University University of Western Australia and Kwinana Industry . • Department of Conservation and Environment Perth Western Australia Report 10 December 1982 Acknowledgements Editor: Vincent Paparo Report preparation: Vincent Paparo Ken Rayner Peter Rye John Rosher Contributions: Bruce Hamilton Charlie Welk er Proof reading: June Hutchison Artwork: Tony Berman Design/ layout: Brian Stewart Cover photography: Stuart Chape Front Cover: Kwinana industry with Wattleup and Thompson Lake in the background. Back Cover: K winana industrial strip looking south. PREFACE In 1974, the Coogee Air Pollution Study recommended that an area of land to the north of major industry at K winana was unsuitable for urban development as a result of the levels of air pollution it experienced. The Kwinana Air Modelling Study (KAMS) grew out of the need to determine the air pollution impact on a wider scale at Kwinana and built upon the earlier pioneering work. As suggested by its name, KAMS was largely concerned with the development and use of mathematical models to estimate air pollution dispersion. The choice of K winana as the location of the first major air dispersion modelling study attempted in Western Australia was ideal. In the first instance, the results of KAMS have an important and immediate planning application to ensure that the adverse impact of air pollution at K winana is kept to a minimum. -

The Railway Line to Broken Hill

RAILS TO THE BARRIER Broken Hill as seen from the top of the line of Lode. The 1957 station is in the right foreground. Image: Gary Hughes ESSAYS TO COMMEMORATE THE CENTENARY OF THE NSW RAILWAY SERVING BROKEN HILL. Australian Railway Historical Society NSW Division. July 2019. 1 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION........................................................................................ 3 HISTORY OF BROKEN HILL......................................................................... 5 THE MINES................................................................................................ 7 PLACE NAMES........................................................................................... 9 GEOGRAPHY AND CLIMATE....................................................................... 12 CULTURE IN THE BUILDINGS...................................................................... 20 THE 1919 BROKEN HILL STATION............................................................... 31 MT GIPPS STATION.................................................................................... 77 MENINDEE STATION.................................................................................. 85 THE 1957 BROKEN HILL STATION................................................................ 98 SULPHIDE STREET STATION........................................................................ 125 TARRAWINGEE TRAMWAY......................................................................... 133 BIBLIOGRAPHY.......................................................................................... -

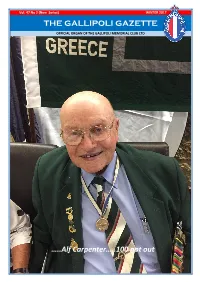

Alf Carpenter…..100 Not Out

Vol. 47 No 2 (New Series) WINTER 2017 THE GALLIPOLI GAZETTE OFFICIAL ORGAN OF THE GALLIPOLI MEMORIAL CLUB LTD …..Alf Carpenter…..100 not out 1 EDITORIAL…….. This edition carries a full report on the Gallipoli Art celebration and presented Alf Carpenter with a Prize which again attracted a broad range of entries. certificate of Club Life Membership. We also look at the commemoration of Anzac Day The elevation of John Robertson to Club President at the Club which included the HMAS Hobart at the April Annual Meeting sees the continuity of Association and was highlighted by the 2/4th the strong leadership the Club has benefitted from Australian Infantry Battalion Reunion which over past decades since the Club was lifted out of doubled as celebration of the 100th birthday three financial uncertainty in the early 1990s. "Robbo" days earlier of its Battalion Association President for joined the Committee in 1991 along with outgoing the past 33 years, Alf Carpenter. President Stephen Ware and myself. So, I know first- The numbers at the reunion lunch were bolstered hand of John's strong commitment over many years by the many friends Alf has made among the to the Club and its ideals. The Club also owes a families of his World War Two mates and the massive debt to retiring President Stephen Ware, support he has given to those families as the ranks who has stepped down to be a Committee member of the 2/4th diminished over the years. The new for continuity. Thank you Stephen for your visionary Gallipoli Club President, John Robertson, joined the leadership and prudent financial management over three decades. -

Finding List for the Janet Fairbank Collection

r 10 FINDING LIST FOR THE JANET FAIRBANK COLLECTION The Newberry Library, Chicago October 1984 • FINDING LIST FOR THE JANET FAIRBANK COLLECTION The Janet Fairbank Collect ion is an uncatalogued collect:;ion of sheet music and "$ .-:,' ~ , music anthologies, housed in boxes and folders in the GeneJ:ClJ. CollectionS" of 'r J . '-::;..... ~'-' .'~ - -.,: - :~~,___ _'-r ... '. I The Newberry Library. The boxes are divided by the nat~onality of the composer, as follows: 8 American 5 French 2v,German 2 British 1 Spanish and Portuguese 1 Scandinavian, Russian and Hungarian 1 Italian 3 English and French anthologies 1 miscellaneous arias, songs and vocalises 1 orchestrations Within these boxes, the music is arranged in folders, alphabetically by composer. The American songs in this finding list are described by composer, title, lyricist if known, and date of publication or manuscript if applicable; the Europeans songs are usually described by composer and title only. When requesting material from the Janet Fairbank Collection, please write the following information on the call slip: Janet Fairbank Collection CAll Cf Country N1:MBER AtJTHOR RS Box number FS ~ PS Folder number RE Composer IU Title(s) of songes) RN No call number is used. THE· NEWBERRY' LIBRARY DESK A M f'LE:) :-lUMBER SCHOOL OR COLLEGE For more information about the history of the collection and the life of Janet Fairbank, please see the work by Edith Borroff, "The Fairbank Collection." A copy is shelved in the Reference and Bibliographical Center, on the Newberry Checklist Index Table. The call number is oML 88 .F35 B6. / E. Miller ~ FAIRBANK COLLECTION AMERICAN - Box 1 Folder 1 All enbr 0 ok Ash Wednesday - aria (Eliot) mss. -

Culture and Customs of Australia

Culture and Customs of Australia LAURIE CLANCY GREENWOOD PRESS Culture and Customs of Australia Culture and Customs of Australia LAURIE CLANCY GREENWOOD PRESS Westport, Connecticut • London Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Clancy, Laurie, 1942– Culture and customs of Australia / Laurie Clancy. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0–313–32169–8 (alk. paper) 1. Australia—Social life and customs. I. Title. DU107.C545 2004 306'.0994 —dc22 2003027515 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data is available. Copyright © 2004 by Laurie Clancy All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, by any process or technique, without the express written consent of the publisher. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 2003027515 ISBN: 0–313–32169–8 First published in 2004 Greenwood Press, 88 Post Road West, Westport, CT 06881 An imprint of Greenwood Publishing Group, Inc. www.greenwood.com Printed in the United States of America The paper used in this book complies with the Permanent Paper Standard issued by the National Information Standards Organization (Z39.48–1984). 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 To Neelam Contents Preface ix Acknowledgments xiii Chronology xv 1 The Land, People, and History 1 2 Thought and Religion 31 3 Marriage, Gender, and Children 51 4 Holidays and Leisure Activities 65 5 Cuisine and Fashion 85 6 Literature 95 7 The Media and Cinema 121 8 The Performing Arts 137 9 Painting 151 10 Architecture 171 Bibliography 185 Index 189 Preface most americans have heard of Australia, but very few could say much about it.