Military Architecture Being Now out of Print, It Has Been Thought Well to Issue a Third Edition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

French Riviera Côte D'azur

10 20 FRENCH RIVIERA CÔTE D’AZUR SUGGESTIONS OF EXCURSIONS FROM THE PORT OF SUGGESTIONS D’EXCURSIONS AU DÉPART DU PORT DE CANNES EXCURSIONS FROM DEPARTURE EXCURSIONS AU DÉPART DE CANNES WE WELCOME YOU TO THE FRENCH RIVIERA Nous vous souhaitons la bienvenue sur la Côte d’Azur www.frenchriviera-tourism.com The Comité Régional du Tourisme (Regional Tourism Council) Riviera Côte d’Azur, has put together this document, following the specific request from individual cruise companies, presenting the different discovery itineraries of the towns and villages of the region pos- sible from the port, or directly the town of Cannes. To help you work out the time needed for each excursion, we have given an approximate time of each visit according the departure point. The time calculated takes into account the potential wait for public transport (train or bus), however, it does not include a lunch stop. We do advice that you chose an excursion that gives you ample time to enjoy the visit in complete serenity. If you wish to contact an established incoming tour company for your requirements, either a minibus company with a chauffeur or a large tour agency we invite you to consult the web site: www.frenchriviera-cb.com for a full list of the same. Or send us an e-mail with your specific requirements to: [email protected] Thank-you for your interest in our destination and we wish you a most enjoyable cruise. Monaco/Monte-Carlo Cap d’Ail Saint-Paul-de-Vence Villefranche-sur-Mer Nice Grasse Cagnes-sur-Mer Villeneuve-Loubet Mougins Biot Antibes Vallauris Cannes Saint-Tropez www.cotedazur-tourisme.com Le Comité Régional du Tourisme Riviera Côte d’Azur, à la demande d’excursionnistes croisiéristes individuels, a réalisé ce document qui recense des suggestions d’itinéraires de découverte de villes et villages au départ du port de croisières de Cannes. -

Genealogical History of the Noble Families Fr Om Tuscany and Umbria Recounted by D

A few days ago, our common friend and Guadagni historian Henri Guignard, from Boutheon, Lyon, France, has sent me by email an old book written in 1668, 202 years before Passerini’s book, on the history and genealogy of the noble families of Tuscany in 17th century Italian, with many pages on the history of the Guadagni. It is a fascinating document, starting to relate the family history before the year 1000, so more than a century before Passerini, and I will start translating it hereafter. GENEALOGICAL HISTORY OF THE NOBLE FAMILIES FR OM TUSCANY AND UMBRIA RECOUNTED BY D. Father EUGENIO GAMURRINI Monk from Cassino, Noble from Arezzo, Academic full of passion, Abbot, Counselor and Ordinary Alms Giver OF HIS VERY CHRISTIAN MAJESTY LOUIS XIV, KING OF FRANCE AND OF NAVARRE, Theologian and Friend of HIS VERY SEREINE HIGHNESS COSIMO III Prince of Tuscany dedicated to the SAME HIGHNESS, FIRST VOLUME IN FLORENCE, In Francesco Onofri’s Printing House. 1668. With license of the Superiors. Louis XIV, King of France, known as the Sun King, 1638-1715 Cosimo III, Granduke of Tuscany, 1642-1723 Cosimo III as a child (left) and as a young man (right) THE GUADAGNI FAMILY FROM FLORENCE The Guadagni Family is so ancient and has always been so powerful in wealth and men that some people believe that they could originate from the glorious family of the Counts Guidi, as the latter owned many properties in proximity of the large fiefs of the former; however, after having made all the possible researches, we were unable to prove this hypothesis; on the other hand, we can confortably prove that they originate from families now extinct; to illustrate this opinion we will now tell everything we found. -

L'artillerie Légère Nousantarienne. a Propos De Six Canons Conservés Dans Des Collections Portugaises Pierre-Yves Manguin

L’artillerie légère nousantarienne. A propos de six canons conservés dans des collections portugaises Pierre-Yves Manguin To cite this version: Pierre-Yves Manguin. L’artillerie légère nousantarienne. A propos de six canons conservés dans des collections portugaises. Arts Asiatiques, École française d’Extrême-Orient, 1976, 32 (1), pp.233 - 268. 10.3406/arasi.1976.1103. halshs-02509117 HAL Id: halshs-02509117 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-02509117 Submitted on 16 Mar 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Arts asiatiques L'artillerie légère nousantarienne. A propos de six canons conservés dans des collections portugaises Pierre-Yves Manguin Citer ce document / Cite this document : Manguin Pierre-Yves. L'artillerie légère nousantarienne. A propos de six canons conservés dans des collections portugaises. In: Arts asiatiques, tome 32, 1976. pp. 233-268; doi : https://doi.org/10.3406/arasi.1976.1103 https://www.persee.fr/doc/arasi_0004-3958_1976_num_32_1_1103 Fichier pdf généré le 20/04/2018 L'ARTILLERIE LÉGÈRE NOUSANTARIEME A PROPOS DE SIX CANONS CONSERVÉS DANS DES COLLECTIONS PORTUGAISES > par Pierre-Yves MANGVIN Lors d'une visite à Macao en 1973, j'eus la surprise de découvrir dans une salle du Musée Luis de Gamôes un très beau spécimen de canon (pièce F). -

Isurium Brigantum

Isurium Brigantum an archaeological survey of Roman Aldborough The authors and publisher wish to thank the following individuals and organisations for their help with this Isurium Brigantum publication: Historic England an archaeological survey of Roman Aldborough Society of Antiquaries of London Thriplow Charitable Trust Faculty of Classics and the McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, University of Cambridge Chris and Jan Martins Rose Ferraby and Martin Millett with contributions by Jason Lucas, James Lyall, Jess Ogden, Dominic Powlesland, Lieven Verdonck and Lacey Wallace Research Report of the Society of Antiquaries of London No. 81 For RWS Norfolk ‒ RF Contents First published 2020 by The Society of Antiquaries of London Burlington House List of figures vii Piccadilly Preface x London W1J 0BE Acknowledgements xi Summary xii www.sal.org.uk Résumé xiii © The Society of Antiquaries of London 2020 Zusammenfassung xiv Notes on referencing and archives xv ISBN: 978 0 8543 1301 3 British Cataloguing in Publication Data A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. Chapter 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Background to this study 1 Library of Congress Cataloguing in Publication Data 1.2 Geographical setting 2 A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the 1.3 Historical background 2 Library of Congress, Washington DC 1.4 Previous inferences on urban origins 6 The moral rights of Rose Ferraby, Martin Millett, Jason Lucas, 1.5 Textual evidence 7 James Lyall, Jess Ogden, Dominic Powlesland, Lieven 1.6 History of the town 7 Verdonck and Lacey Wallace to be identified as the authors of 1.7 Previous archaeological work 8 this work has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. -

Fortification Renaissance: the Roman Origins of the Trace Italienne

FORTIFICATION RENAISSANCE: THE ROMAN ORIGINS OF THE TRACE ITALIENNE Robert T. Vigus Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2013 APPROVED: Guy Chet, Committee Co-Chair Christopher Fuhrmann, Committee Co-Chair Walter Roberts, Committee Member Richard B. McCaslin, Chair of the Department of History Mark Wardell, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Vigus, Robert T. Fortification Renaissance: The Roman Origins of the Trace Italienne. Master of Arts (History), May 2013, pp.71, 35 illustrations, bibliography, 67 titles. The Military Revolution thesis posited by Michael Roberts and expanded upon by Geoffrey Parker places the trace italienne style of fortification of the early modern period as something that is a novel creation, borne out of the minds of Renaissance geniuses. Research shows, however, that the key component of the trace italienne, the angled bastion, has its roots in Greek and Roman writing, and in extant constructions by Roman and Byzantine engineers. The angled bastion of the trace italienne was yet another aspect of the resurgent Greek and Roman culture characteristic of the Renaissance along with the traditions of medicine, mathematics, and science. The writings of the ancients were bolstered by physical examples located in important trading and pilgrimage routes. Furthermore, the geometric layout of the trace italienne stems from Ottoman fortifications that preceded it by at least two hundred years. The Renaissance geniuses combined ancient bastion designs with eastern geometry to match a burgeoning threat in the rising power of the siege cannon. Copyright 2013 by Robert T. Vigus ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis would not have been possible without the assistance and encouragement of many people. -

December 1904

tlbe VOL XVI. DECEMBER, 1904. No. 6. CHANTILLY CASTLE. 'X every country there are a certain number of resi- dences palaces or castles which are known to all, whose names are bound up with the nation's story, and which are representative, if I may use the term, of the different periods of civilization through which they have come down to us. The picturesque outlines of their towers, balustrades and terraces illus- trate and embellish the pages of history. They tell us of the private life of those who for a short while have occupied the world's stage, showing us what were those persons' ideas of comfort and luxury, their artistic tastes, how they built their habitations and laid out their parks and gardens. Thus these edifices belong to the history of architecture using this word not in its strict meaning of con- struction, but in that of mother and protectress of all the plastic arts. They evoke a vanished past, a past, however, of which we are the outcome. One cannot look without emotion upon such ancient and historical edifices as those at Blois, Fontainebleau, Versailles and Chantilly, not to mention others. Ibis article proposes to deal with Chantilly Castle, in order to show the parts it has successively played in French history during the last four hundred years. Chantilly was never a royal residence. In the sixteenth century it belonged to one of the leading families of France, the Montmorencys, and from the seventeenth to a ;'younger branch of the royal family, viz., the Conde branch. Its 'history is as dramatic as the history of France itself, being, in fact, 'an epitome of the latter. -

Tiburzio Spannocchi's Project for the Fortifications of Fuenterrabía in 1580

This paper is part of the Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Defence Sites: Heritage and Future (DSHF 2016) www.witconferences.com Tiburzio Spannocchi’s project for the fortifications of Fuenterrabía in 1580 R. T. Yáñez Pacios & V. Echarri Iribarren University of Alicante, Spain Abstract Fuenterrabía (Hondarribia) is a town located on the Franco-Spanish border. Between the 16th and 19th centuries it was considered to be one of the most outstanding strongholds in the Basque Country due to its strategic position. The bastion system of fortification was extremely prevalent in this stronghold. It was one of the first Spanish towns to adopt the incipient Renaissance designs of the bastion. The military engineers subsequently carried out continuous fortification projects that enabled the structure to withstand the advances being made in artillery and siege tactics. After the construction of the citadel of Pamplona had begun in 1571, following the design of the prestigious military engineer, Jacobo Palear Fratín and being revised by Viceroy Vespasiano Gonzaga, the afore- mentioned engineer undertook an ambitious project commissioned by Felipe II to modernise the fortifications of Fuenterrabía. Neither the plans nor the report of this project have been conserved, but in the year 2000, César Fernández Antuña published the report written by Spannocchi on the state of the fortifications of Fuenterrabía when he arrived to the Spanish peninsula, discovered in the Archivo Histórico Provincial de Zaragoza. This document conducts an in-depth analysis of Spannocchi’s project and how it was related to Fratín’s previous project. It concludes that this project encountered problems in updating the new bastions at the end of the 16th century, and identifies the factors which prevented the stronghold from being extended as was the case in Pamplona after Fratín’s project. -

The Power of the Popes

THE POWER OF THE POPES is eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at hp://www.gutenberg.org/license. Title: e Power Of e Popes Author: Pierre Claude François Daunou Release Date: Mar , [EBook #] Language: English Character set encoding: UTF- *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE POWER OF THE POPES*** Produced by David Widger. ii THE POWER OF THE POPES By Pierre Claude François Daunou AN HISTORICAL ESSAY ON THEIR TEMPORAL DOMINION, AND THE ABUSE OF THEIR SPIRITUAL AUTHORITY Two Volumes in One CONTENTS TRANSLATORS PREFACE ADVERTISEMENT TO THE THIRD EDITION, ORIGINAL CHAPTER I. ORIGIN OF THE TEMPORAL POWER OF THE POPES CHAPTER II. ENTERPRIZES OF THE POPES OF THE NINTH CENTURY CHAPTER III. TENTH CENTURY CHAPTER IV. ENTERPRISES OF THE POPES OF THE ELEVENTH CEN- TURY CHAPTER V. CONTESTS BETWEEN THE POPES AND THE SOVEREIGNS OF THE TWELFTH CENTURY CHAPTER VI. POWER OF THE POPES OF THE THIRTEENTH CENTURY CHAPTER VII. FOURTEENTH CENTURY CHAPTER VIII. FIFTEENTH CENTURY CHAPTER IX. POLICY OF THE POPES OF THE SIXTEENTH CENTURY CHAPTER X. ATTEMPTS OF THE POPES OF THE SEVENTEENTH CEN- TURY CHAPTER XII. RECAPITULATION CHRONOLOGICAL TABLE ENDNOTES AND iv TO THE REV. RICHARD T. P. POPE, AT WHOSE SUGGESTION IT WAS UNDERTAKEN, THIS TRANSLATION OF THE PAPAL POWER IS INSCRIBED, AS A SMALL TRIBUTE OF RESPET AND REGARD BY HIS AFFECTIONATE FRIEND, THE TRANSLATOR. TRANSLATORS PREFACE HE Work of whi the following is a translation, had its origin in the trans- T actions whi took place between Pius VII. -

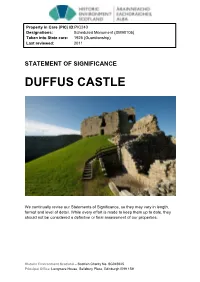

Duffus Castle Statement of Significance

Property in Care (PIC) ID:PIC240 Designations: Scheduled Monument (SM90105) Taken into State care: 1925 (Guardianship) Last reviewed: 2011 STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE DUFFUS CASTLE We continually revise our Statements of Significance, so they may vary in length, format and level of detail. While every effort is made to keep them up to date, they should not be considered a definitive or final assessment of our properties. Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH © Historic Environment Scotland 2018 You may re-use this information (excluding logos and images) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit http://nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open- government-licence/version/3/ or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: [email protected] Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. Any enquiries regarding this document should be sent to us at: Historic Environment Scotland Longmore House Salisbury Place Edinburgh EH9 1SH +44 (0) 131 668 8600 www.historicenvironment.scot You can download this publication from our website at www.historicenvironment.scot Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH DUFFUS CASTLE SYNOPSIS Duffus Castle is the best-preserved motte-and-bailey castle in state care. It was built c.1150 by Freskin, a Fleming who founded the powerful Moray (Murray) dynasty. -

Fortification of the Medieval Fort Isar – Shtip

Trajče NACEV Fortification of the Medieval Fort Isar – Shtip UDK 94:623.1(497.731)”653” University “Goce Delcev” Stip [email protected]; [email protected] Abstract: The medieval fort Isar, which was built on top of the ruins of the antique town of Astibo, is located on the hill with a North-South orientation in the central city core. The fortification had its largest increase during the 14th century and from this period we have the best preserved architectonic remains of the fortification. The entire fort is surrounded by fortification walls, with the main entrance in their eastern portion. The suburbs are located on the eastern and southern slopes of the Isar hill. At the highest part (the acropolis) there was another, smaller fortification, probably a feudal residence with a remarkable main tower (Donjon). The article reviews the fortification in the context of the results from the 2001 – 2002 and 2008 – 2010 excavation campaigns. During the first campaign, one of the most significant discoveries was the second tower, a counterpart to the main Donjon tower, and the entrance to the main part of the acropolis positioned between them. With the second 2008 – 2010 campaign, the entire eastern fortification wall of the Isar fort was uncovered. Key words: fortification, fort, curtain wall, tower. The medieval fort Isar (Fig. 1) (Pl. 1) that sprouted on the ruins of the ancient city Astibo, is located on a dominant hill between the Bregalnica river from the north and west and Otinja from the south and east, in the downtown core, in the north –south direction. -

Raid 06, the Samurai Capture a King

THE SAMURAI CAPTURE A KING Okinawa 1609 STEPHEN TURNBULL First published in 2009 by Osprey Publishing THE WOODLAND TRUST Midland House, West Way, Botley, Oxford OX2 0PH, UK 443 Park Avenue South, New York, NY 10016, USA Osprey Publishing are supporting the Woodland Trust, the UK's leading E-mail: [email protected] woodland conservation charity, by funding the dedication of trees. © 2009 Osprey Publishing Limited ARTIST’S NOTE All rights reserved. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private Readers may care to note that the original paintings from which the study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright, colour plates of the figures, the ships and the battlescene in this book Designs and Patents Act, 1988, no part of this publication may be were prepared are available for private sale. All reproduction copyright reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by whatsoever is retained by the Publishers. All enquiries should be any means, electronic, electrical, chemical, mechanical, optical, addressed to: photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright owner. Enquiries should be addressed to the Publishers. Scorpio Gallery, PO Box 475, Hailsham, East Sussex, BN27 2SL, UK Print ISBN: 978 1 84603 442 8 The Publishers regret that they can enter into no correspondence upon PDF e-book ISBN: 978 1 84908 131 3 this matter. Page layout by: Bounford.com, Cambridge, UK Index by Peter Finn AUTHOR’S DEDICATION Typeset in Sabon Maps by Bounford.com To my two good friends and fellow scholars, Anthony Jenkins and Till Originated by PPS Grasmere Ltd, Leeds, UK Weber, without whose knowledge and support this book could not have Printed in China through Worldprint been written. -

Photogrammetry As a Surveying Technique

PHOTOGRAMMETRY AS A SURVEYING TECHNIQUE APPLIED TO HERITAGE CONSTRUCTIONS RECORDING - ADVANTAGES AND LIMITATIONS VOLUME II João Ricardo Neff Valadares Gomes Covas Dissertação de Natureza Científica para obtenção do Grau de Mestre em ARQUITECTURA Orientação Professor Auxiliar Luis Miguel Cotrim Mateus Professor Auxiliar Victor Manuel Mota Ferreira Constituição do Júri Presidente: Professor Auxiliar Jorge Manuel Tavares Ribeiro Vogal: Professora Auxiliar Cristina Delgado Henriques DOCUMENTO DEFINITIVO Lisboa, FAUL, Dezembro de 2018 PHOTOGRAMMETRY AS A SURVEYING TECHNIQUE APPLIED TO HERITAGE CONSTRUCTIONS RECORDING - ADVANTAGES AND LIMITATIONS VOLUME II João Ricardo Neff Valadares Gomes Covas Dissertação de Natureza Científica para obtenção do Grau de Mestre em ARQUITECTURA Orientação Professor Auxiliar Luis Miguel Cotrim Mateus Professor Auxiliar Victor Manuel Mota Ferreira Constituição do Júri Presidente: Professor Auxiliar Jorge Manuel Tavares Ribeiro Vogal: Professora Auxiliar Cristina Delgado Henriques DOCUMENTO DEFINITIVO Lisboa, FAUL, Dezembro de 2018 INDEX OF CONTENTS Index of Contents ........................................................................................................................... i Index of Figures ............................................................................................................................. v Index of Tables ............................................................................................................................. vii ANNEX 1 – ADDITIONAL TEXTS – STATE